When I was small it was believed in high-minded progressive circles that fairy tales were unsuitable for children. “Does not Cinderella interject a social and economic situation which is both confusing and vicious?… Does not ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ delay a child’s rationalizing of the world and leave him longer than is desirable without the beginnings of scientific standards?” as one child education expert, Lucy Sprague Mitchell, put it in the Foreword to her Here and Now Story Book, which I received for my fifth birthday. It would be much better, she and her colleagues thought, for children to read simple, pleasant, realistic stories which would help to prepare us for the adult world.

Mrs. Mitchell’s own contribution to literature was a squat volume, sunny orange in color, with an idealized city scene on the cover. Inside I could read about The Grocery Man (“This is John’s Mother. Good Morning, Mr. Grocery Man”) and How Spot Found a Home. The children and parents in these stories were exactly like the ones I knew, only more boring. They never did anything really wrong, and nothing dangerous or surprising ever happened to them—no more than it did to Dick and Jane, whom I and my friends were soon to meet in first grade.

After we grew up, of course, we found out how unrealistic these stories had been. The simple, pleasant adult society they had prepared us for did not exist. The fairy tales had been right all along—the world was full of hostile, stupid giants and perilous castles and people who abandoned their children in the nearest forest. To succeed in this world you needed some special skill or patronage, plus remarkable luck; and it didn’t hurt to be very good-looking. The other qualities that counted were wit, boldness, stubborn persistence, and an eye for the main chance. Kindness to those in trouble was also advisable—you never knew who might be useful to you later on.

The fairy tales were also way ahead of Mrs. Mitchell with respect to women’s liberation. In her stories men drove wagons and engines and boats, built houses, worked in stores, and ran factories; women did nothing except look after children and go shopping. The traditional folk tale, on the other hand, is one of the few sorts of classic children’s literature of which a radical feminist would approve. Most of these stories are in the literal sense old wives’ tales. Throughout Europe (except in Ireland) the storytellers from whom the Grimm Brothers and their followers heard them were most often women; in some areas, they were all women.

Quite logically, writers like Robert Graves have seen in many familiar fairy tales survivals of an older matriarchal culture and faith. These stories suggest a society in which women are as competent and active as men, at every age and in every class. Gretel, not Hansel, defeats the Witch; and for every clever youngest son there is a youngest daughter equally resourceful. The contrast is greatest in maturity, where women are often more powerful than men. Real help for the hero or heroine comes most frequently from a fairy godmother or wise woman; and real trouble from a witch or wicked stepmother. With a frequency which recalls current feminist polemics, the significant older male figures are either dumb, male-chauvinist giants or malevolent little dwarfs.

To prepare children for women’s liberation, therefore, and to protect them against Future Shock, you had better buy at least one collection of fairy tales. But which one?

The choice involves two variables, pictures and text. The first is easier; even when you are standing in a hot, crowded bookstore the week before Christmas it is possible to reject the sort of illustrations which look like the backs of cereal boxes. After consultation with a group of experts aged eight to fifteen, I suggest also discarding books with pretty-pretty artistic pictures in which lack of accuracy is disguised by romantic washes of pink and blue. Children, unlike many adults of little imagination, do not believe that the imaginative is identical with the vague; they notice and object when the Witch’s house is obviously not made of gingerbread. Even less desirable are illustrations which derive from modern art. These usually run to heavily patterned woodcuts or silkscreen prints in muddy shades of green and purple, in which it is impossible to tell the princess from the wallpaper.

In choosing a text, the editor of a book of fairy tales can either reproduce the original version as collected in the field, or he can retell the story—with the object of making it more elegant and literary, easier for young children to understand, more moral, or less disturbing.

Fidelity to the original may seem at first the best choice, but it is not as easy as that. The semiliterate elderly rural people who are folklorists’ usual informants tend to repeat themselves and forget episodes. Even the literary version may be incomplete: Perrault’s “Little Red Riding-Hood” ends with both the heroine and her grandmother eaten alive. No last-minute arrival of the Woodman, no miraculous surgical operation, no punishment of the Wolf. A responsible editor has to combine the available versions or select the best of them, which in this case is probably still that of the Brothers Grimm.

Advertisement

Sentimental editors bowdlerize and rewrite, often without admitting it. They speed up the appearance of the Woodman so that he walks in just after the villain has growled his immortal last line, “The better to eat you with, my dear!” The Wolf is chased out the door and disappears in the forest; Grandmother comes out of the closet where she has been hiding, or home from the village. Nobody gets eaten, nobody gets rescued, nobody gets punished. This is supposed to make children feel safer—even though the Wolf is still wandering around outside somewhere, waiting for the next little girl. Possibly truer to current social conditions—but hardly more reassuring.

For younger children, what you will want is essentially a picture book—a selection of the simplest and bestknown tales and fables, simply told. In this category, The Tall Book of Nursery Tales (Harper & Row, 120 pp., $2.50) is still the best buy. Twenty-four stories, and lots of excellent colored illustrations by Feodor Rojankovsky. The book is an unusual shape, very tall and narrow—a little inconvenient to read aloud from, since it won’t stay open, but useful for building bridges. A companion volume for slightly older children, The Tall Book of Fairy Tales, has an equally good text, but the pictures seem to have been drawn by a junior-high-school student of very limited ability.

Fairy Tales and Fables, edited by Eve Morel (Grosset & Dunlap, 125 pp., $4.00) is a large, copiously illustrated volume, new this year. It is handsome to look at, but heavily censored. Miss Morel has included familiar stories from Grimm, Andersen, and Aesop, and two Japanese tales in compliment to the gifted illustrator, Gyo Fujikawa—in addition to some tiresome moral tales about flowers and birds I have never come across before, and suspect of being her very own.

Most expensive and widely available—and therefore probably what your bookstore saleslady will recommend unless she is as perceptive as mine—is The Tenggren Tell-It-Again Book, edited and adapted by Katherine Gibson (Little, Brown, 200 pp., $4.95). “Now boys and girls will know their fairy tales dressed in the bright colors of Tenggren…. His illustrations will become for them realities.” I hope not; they are Revised Disney—flat, oversimple, commercially cute—Cinderella looks like a Barbie doll. As in animated cartoons, everything (people, houses, trees) seems to be made out of Silly Putty. The text is similarly homogenized, and many of the stories have a moral lesson worked in.

All the best general collections of fairy stories for older children are reprints of books first published from forty to eighty years ago. Foremost among them are those of the folklorist Andrew Lang—the Blue Fairy Book, the Red Fairy Book, and so on through a dozen volumes and colors. The pictures—part pre-Raphaelite, part Art Nouveau, and mostly by H. A. Ford—are mysterious and wonderful. Unfortunately, these books are available with the original illustrations only in paperback (Dover, $1.95), not apt to stand up very well to being left out all night in a tree house.

Equally good is Howard Pyle’s The Wonder Clock, first published in 1887 (Harper & Row, 319 pp., $4.50). This contains twenty-four stories, mostly based upon old but not well-known folk tales; it is beautifully printed and illustrated in the style of William Morris’s fine editions. Similar to it, but not as readily available, is Pyle’s Pepper and Salt (Harper & Row, 109 pp., $3.95).

Walter de la Mare’s Tales Told Again (Knopf, 207 pp., $3.95) includes nineteen stories, mostly the familiar ones, retold in simple but impeccable prose. This book, originally published in 1927 with elegant decorations by A. H. Watson, was for years one of the best modern collections of fairy stories. For some unfathomable reason the publishers have chosen to reissue it with new flimsy, comic illustrations which utterly contradict the spirit of the text.

Most collections of tales for older children today tend to be specialized by subject, country, or author. There are books of stories about giants or mermaids or dragons for boys and girls with a particular obsession (The Book of Dragons, etc., by Ruth Manning-Sanders, Dutton, $3.95). There are dozens of collections of tales from foreign countries, one of which might be useful if the family is about to be posted to Korea or leave for a sabbatical in Spain. Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens (Macmillan, 318 pp., $6.95) is a romantic, rather elaborate retelling of the legends of Fionn, Bran, and the rest by the Irish poet and nationalist. It is complemented by some of Arthur Rackham’s best illustrations, often recalling the Book of Kells.

Advertisement

The classic collections of tales, those of Perrault, Andersen, and the Grimm Brothers, are of course available in many editions. For younger children, the most attractive Grimm I have seen, and certainly an excellent buy, is the one illustrated by Jirí Trnka (Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Paul Hamlyn, 207 pp., $2.95). The stories are well-chosen, and the pictures have the comic charm of European folk art. An elegant reprint in paperback is Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm (Dover, 269 pp., $1.75); fifty-two stories translated by Lucy Crane, with many black-and-white illustrations by Walter Crane. Grimm’s Fairy Tales (Grosset & Dunlap, 373 pp., $2.50) is the standard modern inexpensive edition: fifty-five stories sparsely illustrated by Fritz Kredel with fairly pedestrian colored drawings; for older children or “young adults.” The complete edition for old adults is German Folk Tales (Southern Illinois University Press, $10.00), translated by Francis P. Magoun, Jr., and Alexander H. Krappe—it includes over 200 tales, many very obscure.

Charles Perrault, on the other hand, only published eleven stories, all wellknown today. The best edition for children available is Perrault’s Complete Fairy Tales (Dodd, Mead, 184 pp., $3.50). Faithful translations of all the tales in addition to three more by his contemporaries; skillful line drawings by W. Heath Robinson.

Hans Christian Andersen is a special case. Most of his stories are not traditional, but original—even kinky. Nevertheless the convention has been established that he is a wonderful children’s author, full of “supreme poetry, magic, and humor,” as one blurb puts it. But the truth is that apart from a few of the best-known tales like “The Ugly Duckling” and “The Emperor’s New Clothes” Andersen is a long-winded, highly mannered, and very down-beat writer. The most common themes of his tales are the maudlin pathos of death and hopeless love of a particularly painful and soppy sort—the desire of the moth for the star, of the Tin Soldier for the dancing doll, or the Little Mermaid for the Prince. Even inanimate objects like the Darning Needle and the Fir Tree suffer from false romantic hopes and come to a piteous end. These are stories for sentimental adolescents, not for children.

If you like crying, however, there are some superb editions of Andersen’s tales to use as kleenex. Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales (Paul Hamlyn, 207 pp., $2.95) is probably the best buy. This is a large volume, containing twenty stories magnificently illustrated in color by Jirí Trnka—but take a look at the picture of Death and the Emperor on page 21 before you give it to any child who has nightmares. Equally fine is Seven Tales by H. C. Andersen (Harper & Row, 128 pp., $3.95), translated by Eva Le Gallienne and marvelously illustrated by Maurice Sendak, with a picture on almost every page. Feminists should note, however, that while most of the males in these stories are brave and modest throughout their many trials, the female characters have all the faults men have traditionally ascribed to women. They are vain, flighty, snobbish, feather-brained, oversensitive, and terrible gossips. Maybe it’s not surprising I don’t care for him, after all.

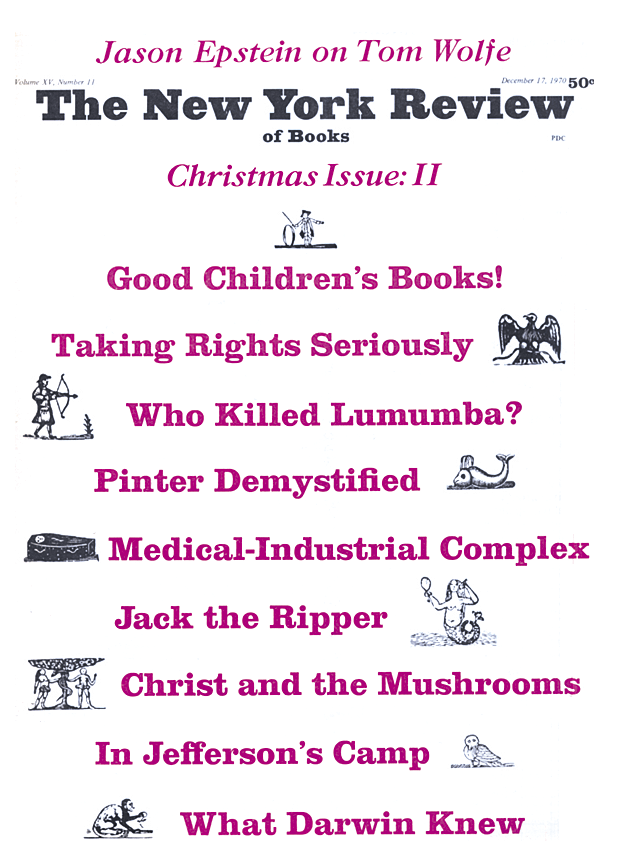

This Issue

December 17, 1970