Four women novelists: Eudora Welty, Jean Rhys, Carol Hill, and “Lawrence Durrell.” They can usher in the graceful words with which Sir Walter Scott bowed out, after praising Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen, and a great many more:

It would be impossible to match against these names the same number of masculine competitors, arising within the same space of time. The fact is worthy of notice; although, whether it arises from mere chance; whether the less marked and evanescent shades of modern society are more happily painted by the finer pencil of a woman; or whether our modern delicacy, having excluded the bold and sometimes coarse delineations permitted to ancient novelists, has rendered competition more easy to female writers, because the forms must be veiled and clothed with drapery,—is a subject which would lead us far, and which, therefore, it is not our present purpose to enter into.

Exit Scott in 1825. Enter Virginia Woolf in 1918, with a cool list of drastic questions about “the women novelists.” By 1970, “our modern delicacy” is not quite what it was, and Scott is to be suspected of insufferably male gallantry, of paying women novelists a compliment rather than doing them justice.

But first the “Lawrence Durrell” affair. It is no coincidence that it should have been Nunquam which has at last blown the gaff, and has revealed to a mildly surprised world that “Lawrence Durrell” is the anagrammatic pseudonym of Ellen Ward Curler, a fragile relic of the Twenties who was one of the founder members (the other members soon foundered) of the Ladies’ Liberation Front. Aged sixty-nine, she now lives on Lesbos, and she has let it be known to Private Eye (whose scoop all this is) that the only point of all her “Lawrence Durrell” books has been to make financially possible her long-standing enterprise of translating “Homer” (that other great authoress) into English Sapphics.

Anyway, that the disclosure should have been precipitated by Nunquam is no accident, since the novel is itself an allegory of the whole hoax. Frankenstein was “A Modern Prometheus”; Nunquam is a modern Frankenstein. But Ellen Ward Curler has seen that Mary Shelley should have stood by the rights of women; the new fatal simulacrum has to be, not a man, but a femme fatale. “We don’t really need a male dummy, do we?”—what the character means (he is lusting for the female dummy) is not at all the same as what the authoress means (male dummies we do not need expensively to make).

Nunquam wraps up the story of Tunc (1968), and it makes clear just what was involved in that earlier anagram. Has she not reason to lament what man has made of woman? And what apter fable could there be than that of a synthetic woman such as man insists woman must be? Julian, the wizard of the great concern “Merlin” which is taking over the world, bends everyone’s scientific skill to the creation of his computerized nylon woman; his Iolanthe is to be brought back to life, complete with memory-bank and sexual organs. That it should all end in disaster is no more (the allegory intimates) than men deserve, or than they court. Certainly “Lawrence Durrell” has hit upon a tone of swaggeringly grinning male humorlessness which does more for the Ladies’ Liberation Front than ever Ellen Ward Curler was able to do by chaining herself to those railings.

“Stick your finger in there and feel—a self-lubricating mucous surface imitated to the life.” I felt an awful cringe of misgiving as I did so, albeit reluctantly.

Male lubricity and hypocrisy have seldom been so imitated to the life. Virginia Woolf:

It may have been not only with a view to obtaining impartial criticism that George Eliot and Miss Brontë adopted male pseudonyms, but in order to free their own consciousness as they wrote from the tyranny of what was expected from their sex.

But it has been left to Ellen Ward Curler to adopt her male pseudonym as a means of exposing the jovial tyranny of the male sex.

The only doubts are likely to be about whether the didactic allegory isn’t a bit broad. “Lawrence Durrell” plants her clues well, it is true; the book’s second sentence asks, “If there were a difference how would you recognize it?” and even an inattentive reader will prick up his ears (the book is not for her ears) and murmur vive la différence. But some of the giveaways are less than cheap, they are gratuitous, as when the male narrator is made to speak of his “safe period.”

At times, too, the feminism is so virulent as to shatter the mask. There is the willful destruction of the male counterpart to Iolanthe, her consort—“It’s the man, Adam. He’s a total wreck, a write-off.” Here the punitive feminist, writing off, becomes vengeful. And the same is true of the elaborate account of “Shook Young,” a mass delusion in which men believe that their male organ is retracting itself into their abdomen and will disappear unless they get a grip on themselves. Not without symbolic point, but too exultingly repaying man’s inhumanity to woman with some womanly inhumanity to man.

Advertisement

And what of the impulse which led Ellen Ward Curler to have Julian so vividly castrated? Likewise the rather too naked flash of penis envy which led her to expose “Professor Pfeiffer whose dentures are loose and who has a huge dried black penis on his desk—a veritable Prester John of an organ.” Still, even if the allegory has its hysteria and flagrancies, it does at least make something of this book by “Lawrence Durrell”; taken straight, as a book by Lawrence Durrell, Nunquam would be no more than labored pretentious infantility, the resonance and crackle of hi-sci-fi. But then, as Virginia Woolf said, no one “can possibly mistake a novel written by a man for a novel written by a woman.”

Since Eudora Welty is skilled and upright, and since Losing Battles (her first novel for fifteen years) is ample and meticulous, it is disconcerting when the only sound which one can hear emanating from the book is a twang. Twangs can be plangent but they stay thin. Is it that an Englishman is somehow cut off from an awareness of that substantiality which the American reader finds resonant? Or, more specifically, that Losing Battles asks for a reader who knows something (and not just in his head) of what it was like in rural Mississippi in the 1930s? So even a reviewer may think it prudent to be open-minded (though remembering that the really open-minded man dies intestate). Yet there are things within the book itself which manifest some uneasiness as to whether there ever was created a substance, a palpability, at all answering to the charm and concern which were being brought to bear.

” ‘It’s Belshazzar’s Feast without no Handwriting on the Wall to mar it,’ Brother Bethune went smoothly on.” But though the handwriting on the wall must have marred the feast for the feasters, it absolutely made the feast for readers. So benign is Miss Welty’s vision that she seems to me to have removed from the battles of her title any real sense that people get hurt.

Her formula is a classic one, from Dryden to Chekhov: choosing a long-awaited day. There is a family reunion in Banner for the ninetieth birthday of Granny Vaughn. Jack Renfro is to grace the reunion, home after two years in the state penitentiary. The doings of the novel involve, first, Jack’s relationship with his wife Gloria; second, the fact that Jack finds to his chagrin that the man whose car he has just helped out of a ditch is Judge Moody, who sent him to the penitentiary; and third, the news that “Miss Julia Mortimer dropped dead this morning,” she being the gallant old schoolteacher about whom everybody has a strong opinion. It is the words of one of her letters which furnish the title: “All my life I’ve fought a hard war with ignorance. Except in those cases that you can count off on your fingers, I lost every battle.”

Miss Welty is prepared to take pains but not to give pain. And the losing battles are muffled, muted, thin, because within the world of this book ignorance never seems such a pernicious thing anyway. Ignorance—one has positively to make the effort of recollection—is in fact half-brother to bigotry, superstition, and spite; but Miss Welty’s Mississippi (maybe it was the real one, in which case there cannot be room there now for any other emotion than nostalgia) is miraculously clean. But how then can Miss Julia Mortimer’s life of teaching—so heroic and parochial, so dedicated and capricious, so loving and peremptory—be all that the book claims unless we are shown the true face of ignorance?

They managed to get a coffin for Miss Mortimer although it was Sunday:

Got her one in Gilfoy. It’s a Jew. They don’t believe in Jesus—I reckon Sunday’s just like any other day to him.

And no more about all that dark undergrowth which flourishes in the shade of ignorance. Such ethnic equability is matched through most of the book by a cosmic kindliness. So little harm or pain, so few scars (any?) for Jack in those two years in the penitentiary. But then so little he had done (a shindy, most unmurderous, with a storekeeper buffoon). But then again no festering sense of injustice. Mildness is all. Guns are not lethal, and even when loaded receive affectionate badinage (“and butts him out of that old piece-of-mischief that Curly was whirling to, and it was loaded, you bet”). Snakes are seldom poisonous; bees are virtually stingless; even the cyclone knows a kindly township when it hits one:

Advertisement

“It picked the Methodist Church up all in one piece and carried it through the air and set it down right next to the Baptist Church! Thank the Lord nobody was worshipping in either one,” said Aunt Beck…. “It’s a wonder we all wasn’t carried off, killed with the horses and cows, and skinned alive like the chickens,” said Uncle Curtis. “Just got up and found each other, glad we was all still in the land of the living.”

“You were spared for a purpose, of course,” said Mrs. Moody.

Of course. And yes, things do often work out well. But what won’t square is the combination of such good fortune with the implicit claims to quiet heroism. The same goes for the moral achievements. “Forgiving seems the besetting sin of this house”: much is said, with good-natured irony, about forgiveness. But softened and lessened. Gerontion could ask, “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?” And without some such painful knowledge, what is it to forgive?

“All country people hate each other.” For Hazlitt, this was the crucial fact from which Wordsworth averted his pained and sensitive gaze. Miss Welty’s novel has its Wordsworthian aspirations, and it too suffers from wishfulness, from its unwillingness to posit that there might be anything in such a fierce hyperbole as Hazlitt’s. Yet Miss Welty is too honest (and too shrewd) a writer to leave it there. Hence the sudden somber flashes which are to make us see that the idyl is taking place in what is after all the real world. The word “niggers” surfaces on page 341 (can it be for the first time?), and within a few pages we are to glimpse horror: Uncle Nathan’s stump. Long ago he chopped off his hand because he killed a man “and let ’em hang a sawmill nigger for it.” Yet there is something factitious and rhetorical about this transient shock.

For Miss Welty’s style has its succumbings. Of Oliver Goldsmith—that other creator of melancholy idyl, celebrator of a losing battle—it was said by T. S. Eliot: “his melting sentiment [was] just saved by the precision of his language.” Miss Welty has innumerable felicities, but it is a narrow line which separates a felicity from a complacency. “His urgent face”: and then within three pages, “his perplexed jaw,” “his boiled, well-alarmed face,” “Elvie’s little announcing face.” The turn of phrase has become a turn. Metaphors and similes proliferate, as if in the hope that here indeed there will be a proper density. But too many of them are deceptive: “pink as children’s faces” needs the tautological addendum “…when pink,” and the same goes for “flowers still colorless as faces,” or “his face smileless as a child’s.” Anyway there are, in spurts, simply too many similitudes, a gentle overkill:

At the foot of the road, on which Brother Bethune was trotting down to Banner, the shadow of the bridge on the river floor looked more solid than the bridge, every plank of its uneven floor laid down black, like an old men’s game of dominoes left lying on a sunny table in a courthouse yard at dinner time. Along the bank of the river, the sycamore trees in the school yard were tinged on top with yellow, as though acid had been spilled on them from some travelling spoon. The gas pump in front of Curly’s store stood fading there like a little old lady in a blue sunbonnet who had nowhere to go.

That last simile has an inadvertent poignancy—the simile itself has nowhere to go.

Jeremiah 8:20 is an evocation, not the first, of the American nightmare, but a good new one, too. Carol Hill shows that the dream goes but the pain stays, and I thought of Berryman:

I can’t go into the meaning of the dream

except to say a sense of total LOSS

afflicted me therof:

an absolute disappearance of continuity & love

and children away at school, the weight of the cross,

and everything is what it seems.

The world of that poem—of Mother and the lunatic asylum and a policeman—is the world of Carol Hill’s first novel. The heartbreaking fright of American life is seen, not as a dread that things may be mysteriously other than their appearances (mystery can be coped with), but a bleak dismay at the prospect that there isn’t any mystery at all, that “everything is what it seems.” Brutal, sordid, literal, loveless. Jeremiah is “Jeremiah Francis Scanlon, fat, balding and thirty-nine,” and his story—Mrs. Hill creates it piercingly—is at once deeply heartening and disheartening. For, although it antedates the phrase, it is the story of a humiliated member of the “silent majority”: almost literally so, in that he can’t speak. He has lessons in it. He strains out a word or two, and sinks under the mountainous psychic weight of his fat. Still, he makes progress. He listens, trying hard, to the clever half-truths (half being a lot more than he ever was offered by his fussy, wounding parents) of the intellectual in his boardinghouse:

“You, left to your own devices, would not be, let us say, a dangerous man. But you will not be left to your own devices. Humiliation in itself is a social disease, you see. Although something which one contracts from oneself, it is something which only takes effect in the presence of others. Not only others, but certain carefully positioned others. Do you understand?” “I think so,” Francis said, thoughtfully, trying hard.

A dangerous man. Fat Francis is prime—even primed—for fascism. He is dangerously humiliated, recurrently; utterly frustrated sexually (there is a half-guilty fiasco in the past, and there will be another in the present); and he is thrown by his work as an accountant, an off-white-collar worker, into grubby contact with all the violent bigotries. “They got niggers goin’ to college,” says Ernie, his only friend and no friend to him. And there are blue films in the men’s room at lunchtime. And there is a Negro appointed over him. And there is even ignominious dismissal. All this to the accompaniment, plausibly half-mad, of a conspiracy theory which keeps Francis rotundly patriotic.

Deeply disheartening—and yet it turns out to be the story of a man who doesn’t at all become a fascist. For Francis has happened upon a boardinghouse which houses some people who inadvertently save him. Not by being especially good (they may not be cruel or pigheaded, but they are revolutionaries manqués, bitter, posturing, and less clever than they insist on sounding), but by seeing things so utterly differently from Francis’s thirty-nine-year-old emasculated puerility, so differently from anything he has ever conceived of, as to make him rub his eyes. And Francis proves to be an honest man. “He did not like to think of officials being mad”: the forceful fidelity of Jeremiah 8:20 is in its showing a man reluctantly having to come to some such conclusion, and this is a finer achievement than any clamped leftism which does, very positively, like to think of officials being mad—won’t indeed think of them as anything else.

One of the lodgers, Miles, goes out in drag. Francis sees nothing odd about Miles’s daily insistence that there’s some new dramatic role he’s off to play. Nor does Francis see anything wrong in crying out in shock—when Miles, battered and bloodied, crawls in one night—

“Shouldn’t ya, shouldn’t ya,” Francis said trembling, “shouldn’t ya call the police?” Jocko shot him a look of astonishment. “Good God,” Jocko said, “who do you think did it?”

Those looks of astonishment start to tell upon Francis.

Yet he is doomed as well as saved. Mrs. Hill isn’t sentimental, and she sees that though Francis (and this constitutes some kind of tribute to America) isn’t doomed to a dishonorable disaster, he may still be doomed to an honorable one. There are lunacies which he escapes, but he can’t—given what he is, and given that “everything is what it seems”—escape them all, and a fantastic unmalign one finally encompasses him. I don’t want to say what it is, because the ending of Jeremiah 8:20 (like the sheerly unforgettable ending of Easy Rider, in my opinion) is both apocalyptic and casually credible. It is enough to say that Francis earns the strange tribute which the book pays him (and which the book itself therefore earns), a tribute which begins with a kindly hope of traditional grandiloquence and which ends in shattered syntax:

“You’re not a literary man are you?” Jocko had said, and indeed he shook his head for he was not. But there was something of the sage in him, for at the heart of his unknowing, his unglowing ineptitude was a small burning coal that would not rest, and could not rest until he.

And this touching uncompleted restlessness—touching though ridiculous and even gullible (Francis is the squalid city’s Candide)—is that of a man all but destroyed by his parents before he even started out. Is there anywhere in recent fiction a better account of what R. D. Laing calls the “double bind,” with its cruelly contradictory imperatives?

His mother’s pink face lay flushed behind the glass of the car door. He started at her a moment, under glass.

“Well, get in, dear,” she said, and Francis let his mouth move uncertainly into a crooked smile, then crooking up his hand pressed the fat wet palm of it over the glass covering her face and pink against pink, said, “Hi.”

“You must be hungry,” she said, “I brought you a piece of home-made cake,” and with one hand steering, she shoved a chocolate layer cake on a green paper plate, covered with wax paper, across the seat to Francis.

“I, I coulda waited until we got home,” Francis said, uncomfortable at being baited.

“Well, yes,” the high pitch came back, “I know you could have, I was just trying to be nice,” the high note pierced his ear.

“You don’t have to eat it, dear,” she said, staring straight ahead as Francis plunged into the cake, the crumbs spilling to his lap, “but be sure to wipe your hands. I don’t want chocolate all over the seats.”

And Francis felt again the old vortex rising, “Obey, don’t obey, do, don’t, eat, not, spill not, mess not, wipe not, be not,” and he sucked an extra-long time on a chocolate crumb-encased finger.

Again, Gerontion’s dismay, but this time with the weight of pain: “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?”

T. S. Eliot—and not just because he is the master of pain—comes to mind too for Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight. The first paragraph speaks of “the smell of cheap hotels” (“Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels”), and the second paragraph announces: “I have arranged my little life.” For this is the love song of someone who no longer dares. Good Morning, Midnight was originally published in 1939; it was the climax of Miss Rhys’s fiction (she had been publishing since 1927), and yet after it she virtually gave up writing until a few years ago, when she brought out her bizarre tour de force Wide Sargasso Sea (1966).

The vicissitudes of her reputation resemble those of Christina Stead’s; it is true that her work—unlike Miss Stead’s—has not yet engaged in its passionate defense critics of the caliber of Randall Jarrell and Elizabeth Hardwick, and true too that Good Morning, Midnight—though it is a bitterly distilled and memorable achievement—is in the end less largely penetrating than Miss Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children (1940, reissued 1965).

Miss Rhys’s narrator, Sasha, is acerb, laconic, witty, and done for. Her marriage ruined, her life luckless, her garlands all blasted, all wasted. It is October 1937, and she is revisiting Paris where she had once been perilously happy (or had she?). Perhaps she won’t attempt suicide again, but for that too she pays a price. A price which she insists on exacting; she is always, in all matters of emotion, her own Shylock. “When you’ve been made very cold and very sane you’ve also been made very passive.” She is going down for the third time; her memories of the second time make it clear that nothing has changed:

Now I no longer wish to be loved, beautiful, happy or successful. I want one thing and one thing only—to be left alone. No more pawings, no more pryings—leave me alone…. (They’ll do that all right, my dear.)

And now in Paris there is a man who won’t leave her alone—but he proves to be a gigolo. For a moment there is glimpsed a faint possibility that he might not be just a gigolo; but that possibility is at once occluded by Sasha, since if there is one thing which she now fears more than the unloving it is the loving. She turns him out contemptuously; she then (and here the book is lacerating) fantasies about his return; and it all ends with a desperate “Yes—yes—yes….” which is a grimly anaphrodisiac counterpart to Molly Bloom’s dying fall. Even so, it is hard even to sense with any precision just what it is about this fiercely unforgiving book which so sends it under one’s skin. Perhaps there are rather few such evocations of pain which find no pleasure whatsoever in it.

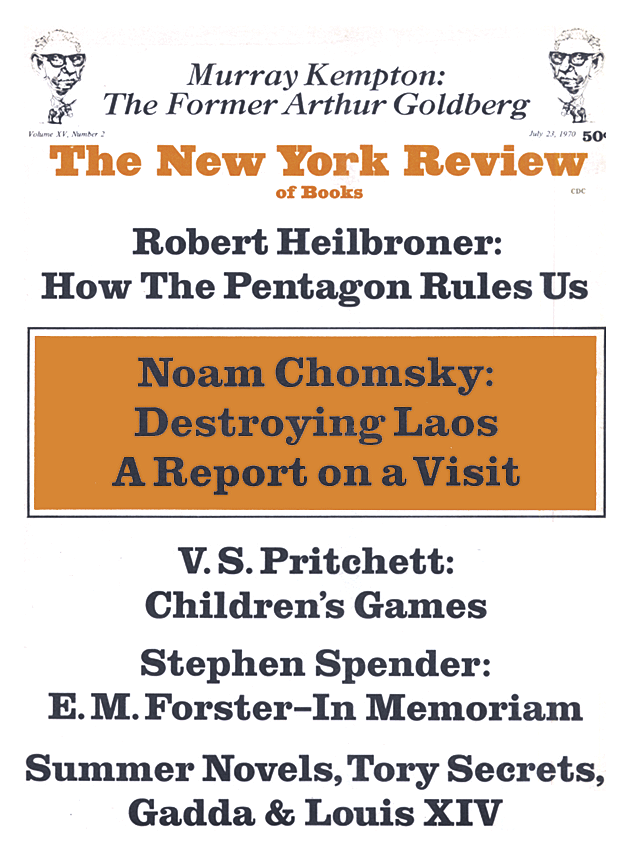

This Issue

July 23, 1970