The appearance of The Cowards in English is the latest episode in the life of what must be one of Europe’s longest-suffering manuscripts. Josef Skvorecký originally wrote this book in Czechoslovakia in 1948-9, when he was only twenty-four. It did not get published. Ten years later he submitted the manuscript of another novel, End of the Nylon Age, which was rejected by the Novotny literary bureaucracy. Irritated, Skvorecký dug out The Cowards again—an enormous bundle of some 800 pages—carved a large novel out of it, and tried that on the authorities.

This time they passed it, an act so astonishing that one suspects malice in view of what followed. The publication of The Cowards by the Writer’s Union led to a disastrous backlash: there were firings in the publishing house, ragings in the official press, and a general purge that extended eventually throughout the arts. In one of those idiotic arguments that occur whenever politicians and writers collide, Skvorecký was left insisting to his critics that even if the hero of the novel had shared in minute detail the experiences of the author in real life, yet the hero could not be taken as “Skvorecký speaking.”

How happy, in retrospect, was Skvorecký to be playing games with the censors in 1958! That was a time of early dawn and green shoots compared to what is going on now. Five years after The Cowards appeared, in 1963, a second edition was published with a cheeky and impenitent Introduction by the author. Today, however, Skvorecký lives and teaches in Canada. Too many dawns without subsequent days, he may reflect, have been the curse of Czech literature. It looked good in 1948; it looked good in 1958; in 1968 it looked very good indeed. Each time, the dawn cooled directly into dusk. Ivan Klimá has said that “Czech culture is the element of continuity in our society.” How much cultural disruption can that society endure without permanent damage?

The Cowards dates from almost a week ago of false dawns. A small town near the German border faces up to imminent liberation in May, 1945. The narrator, a boy with a saxophone, observes his town with the accuracy of Sherwood Anderson; soon he will be leaving for Prague, for a new world, for big city girls. Danny belongs to a jazz band, a group of young men and their girls who watch the town bigwigs preparing for a safe little “revolution” against the Germans once they can be sure there will be no resistance.

The jazzmen (“Bob Crosby-style Dixieland”) take in all this with the disabused yet sentimental interest in the activities of the uninitiated which Mezz Mezzrow would have expected of them. They scorn the official heroics, but wonder queasily how they are going to stand the test themselves. Jazz, however, remains for them the only “real” thing.

Skvorecký has written about this in other stories, but never re-created this state of mind so well. Jazz meant something very special in Europe in 1945: the unofficial liberation. Egon Monk, in his beautiful contribution to the film The First Day of Freedom, made this point through his close-up of a spectacled Berlin kid listening blissfully to “Tuxedo Junction” on the AFN of the approaching Americans, while his house disintegrates about him in those same days of May, 1945.

In The Cowards, the town fathers make their “revolution.” Czech flags are hung out, then whipped in again as the Germans return. The tougher of the town’s youth try to arm themselves as partisans, but obediently give up their glamorous weapons when they are told to. There must be no disorder. The apprentice heroes find themselves patrolling the streets with the Germans, jointly looking out for looters and Bolshevik “disturbers of the peace.” It is a very Czech tale. Only at the end do they all find themselves shooting and killing, as SS tanks retreat through the town with the Russians on their heels. Every day at lunchtime, Danny goes home to be fed a large meal by his mother.

It is not at all the sort of mirror official Czechoslovakia would wish to glance in. A recurring theme is Danny’s pity for the Germans, defeated and bewildered, whose stubbornness in retreat often contrasts well with the way the townsfolk harry and insult them when they think they run no risk by it. Petty bureaucrats make life difficult for the floods of refugees, and suppress their misgivings enough to greet the Russians obsequiously. The Russians strike Danny as alluring primitives (his use of the word “Mongolian” about them caused much of the scandal in 1958); he does not betray “swing” if he likes their twangy music too.

There is a great deal of prelapsarian charm about The Cowards. Saturated in Hemingway and Wolfe, the writing is defiantly self-indulgent. Even after Skvorecký’s jungle clearing operations on the original manuscript, there is too much soliloquy, too much agonizing over Danny’s silly, pretty girl friend, who loves somebody else and won’t give Danny what he wants. But The Cowards, with these faults, is still a triumph. Skvorecký, at twenty-four, survived the tidal waves of false emotion and told the truth.

Advertisement

Joseph seems, at first sight, a curiosity. Mervyn Jones has transformed the life of Stalin into a novel. But this is neither a mere “reconstruction” which decorates a chronicle with dialogue, nor an imitation of those laborious late Upton Sinclair novels in which the insufferable Lanny Budd dashes about like a hijacker on a time machine, instructing historical personalities on their next move. Jones has taken fictionalization a step further. The names of the principal actors of the Revolution and the first Soviet decades have been changed, episodes have been invented, other events telescoped or switched about in time.

This is where opinions about Joseph are going to divide. For many readers, the shadow of the Georgian is too cold and close to be tampered with so confidently. Victor, Leonard, Clem, and Sandra sound more like the stalwarts of a Labour Party branch in outer London than Lenin, Trotsky, Voroshilov, and Kollontaj (and, unlike the reviewer, readers don’t get a publicity slip telling them that Vivian is really Vyacheslav Molotov). Joseph goes to bed with Sandra, and his son turns out to be a homosexual. What’s this?

Jones knows all these objections perfectly well, and doesn’t seem to lose courage. He adds an appendix explaining what he has invented or transposed. He does not tell us why he has done so, except to say that “I have used the facts as novelists often use the facts.” The explanation lies in the book itself, and it is an impressive book. Beginning with the remote birth in Georgia and ending, in effect, with the Red Army parade through Moscow in 1941, the Germans at the gates, and Joseph on the reviewing stand, Jones tries to construct a hypothesis of Stalin’s nature. It is, as it should be, a respectful novel. Joseph slowly emerges from the seminary, from clandestine work and revolution, as a man totally ordinary in his tastes and perceptions, totally extraordinary in the relationship of his loneliness to his will to power. By a pun on both that ordinariness and the derivation of Stalin’s name, Jones calls him “Joseph Smith.”

The book is also about the prime and the fate of the old Bolsheviks. Through the characters of Gregory and Leo and Nicholas and Richard, Mr. Jones tries to raise the ghosts of Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, and Rykov. As in his other novels, In Famine’s Shadow, John and Mary, and A Survivor, he takes particular care to make his women authentic and believable.

Joseph is a moving book, but it does not entirely succeed. Lifting men and events out of the mythic Russian context in order to make them somehow more intimate and familiar was a risk. The dimensions of that episode are of an unalterably mythic scale. Clever Leonard and bald Victor do not quite fit their background, because those who helped to make those times themselves ceased, in some sense, to be “ordinary” people. If the ghosts of Stalin and Beria are to be taken for a walk, then let their closest escort be veracity.

Little Peter in War and Peace is a depressing novel. The blurb’s comparison to Grass is unwise, because it is apposite and entirely to Zwerenz’s disadvantage. A Wunderkind from Saxony flails his way through war and Wirtschaftswunder with swashes of his prodigious member. His name is Michael Casanova and his pedigree can be traced back to the great amorist himself, conceiving a last descendant on his deathbed at Düx. Trollish family dramas surround Michael’s bull-like father, a brickworker in prewar Saxony; hideous and fantastic events attend his son on the Eastern front. A thick sauce of blood, sperm, and relentless “satire” smothers everything in the novel except Michael’s ever-emergent phallus. In the end, just to ram the point home, he breaks his way out of jail with it.

Zwerenz is a better writer than Little Peter suggests; small episodes in this long-winded novel are vivid and alert. But something seems to have given way. Even the idea of the prick as the pike of the revolution is old and unconvincing. Burns, who built up much theory and practice in this area, said: “O, what a peacemaker is a guid well-willy pizzle! It is the mediator, the guarantee, the umpire, the bond of union, the solemn league & covenant, the plenipotentiary….” A subtler idea altogether, an emblem not for Jagger but for Jarring.

Like The Cowards, Dzhagarov’s play The Public Prosecutor belongs very much to a historical moment. But unlike the publication of Skvorecký’s novel, the production of this Bulgarian play in 1964 was a deliberately timed political event in itself; there is an element of “happening” about it, and to read the script today without the context or the audiences (who were reacting to the first open attacks on Bulgarian Stalinism) is only half the experience. It is a straight, serious play, without much fantasy or complexity, about an unjust arrest and the moral travails of those involved in it.

Advertisement

The public prosecutor is asked to sign the arrest warrant of his sister’s lover, whom he considers innocent. While he wavers, the play shifts to the main action, visualizing the situations which his signature would create: first, the bewilderment and scorn of his family and, later, the political thaw in which the prisoner is released and the old wounds reopen. Boyan, the prosecutor’s brother, who has urged him to do his duty in the first instance, craftily helps the victim in jail when he senses the coming change of political weather and emerges as a self-righteous “liberal” denouncing his brother’s crimes against socialist legality.

Dzhagarov believes in de-Stalinization, but by decent Stalinists. He has an instinctive distaste for apostles of liberty, and the play is light-years removed from the experimental writing which exuberantly cast everything into doubt in Poland after 1956. Dzhagarov does not seem to seek “new paths” to socialism; rather, the removal of tragic abuses. He shows sympathy for those who made mistakes, believing them to be necessities of history, and later admitted honestly that they had been mistaken. In an interesting but diffuse and didactic Introduction, Lord Snow praises what he considers to be Dzhagarov’s fundamental pessimism about the relation of man to power. Does Lord Snow see in the prosecutor one of those lay Calvinists who populate his own novels, somehow acquiring a melancholy moral stature by the way they do their duty in a corrupt world? At all events, and at the end of the play, Dzhagarov’s prosecutor refuses to sign.

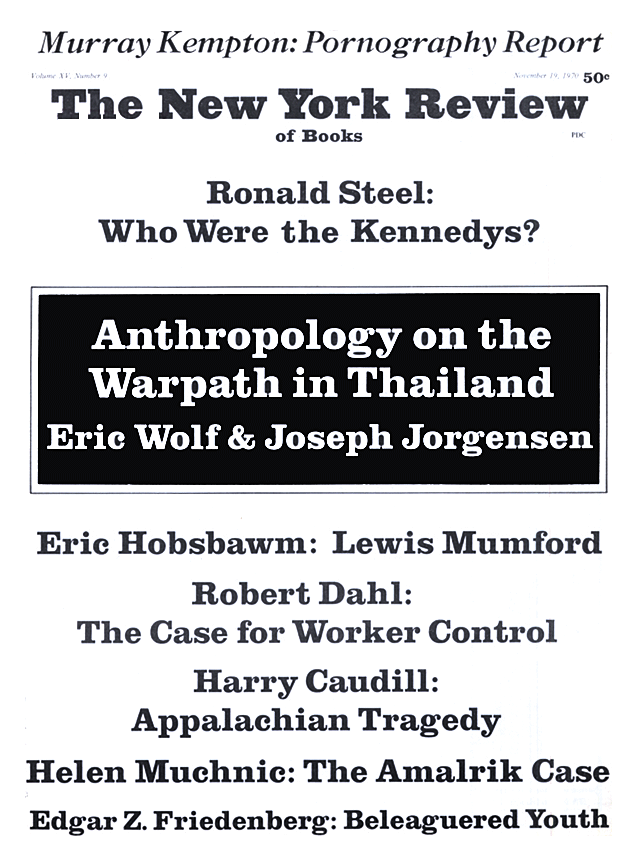

This Issue

November 19, 1970