The second book by Andrei Amalrik—written earlier but published later—is different in substance but not in spirit from the first, and is equally remarkable. The first, an essay entitled Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?,1 is a daring analysis of the Soviet state and a prediction of its doom. When it came out this year, it was generally described as “apocalyptic”; and yet, however startling the conclusions, its argument proceeds unemotionally and logically, with constant, fair-minded admissions of possible error. The second, an autobiography, bears the same quality of rational detachment, and is exceptionally moving because of its composure.

Amalrik writes about himself with the impersonality of a chronicler recording external events. His physical suffering, which has been considerable, is mentioned almost incidentally, and there is very little about his feelings and sensations. The details of the story are harrowing, but there is not a trace of self-pity in it, and his indignation is reserved for the implications of his life, which is interesting, he says, only because it is typical: “What happened to me is not surprising or exceptional in my country. But that is just why it is interesting.”

What happened was that on the 26th of February, 1965, four members of the police force walked into the room where Amalrik was entertaining two Americans who had come to look over his collection of modern pictures and demanded that he accompany them “for a talk.” Amalrik was annoyed and embarrassed, but not surprised. (He was aware that he had been under surveillance for over two years and that one of his neighbors was a spy who informed on him regularly.) Amazed that he refused to budge unless they produced a warrant, the policemen left, but several days later Amalrik received a summons to appear at the Precinct Station of his district. He was liable, he knew, on the charge of “parasitism,” that is, of not having steady employment, but he was questioned also on other matters, such as his relations with foreigners to whom, it was imagined, he sold the “abstract” paintings of his artist friends. Parasitism, however, was the official charge, and he was now given time to find himself a job.

The “anti-parasite” law, adopted in 1961, is directed against those who “avoid socially useful work” and “lead a parasitic way of life.” Although an “administrative” rather than a “criminal” offense, it differs in several ways from other administrative offenses and is punishable by “resettlement,” which is “very similar…to the ‘criminal’ sanctions of banishment and exile.”2 (The poet Josif Brodsky, convicted of this offense in 1964, was given a sentence of five years’ hard labor.) Amalrik describes it as a “punitive measure…meant to kill several birds with one stone: liquidate unemployment, provide a labor force for the remote areas, and cleanse the large cities of their ‘anti-social elements.’ It is also a useful way of dealing with ‘awkward’ intellectuals.” Among the many parasites whom Amalrik was presently to meet, none actually, “except for the professional criminals,” lived “at the expense of others.” The rest were independent workers, carpenters, stovemakers, and the like, who carried on their own businesses in preference to being employed; religious sectarians and intellectuals; drunks (not necessarily habitual alcoholics, but men who, on some special occasion, had indulged in a spree) and drug addicts.

As for Amalrik, there were two reasons he had not worked regularly for nearly a year: firstly, he had to take care of his father, who was almost completely paralyzed and required constant attention; and secondly, he was busy writing plays, which he considered to be his real occupation. Nevertheless, he did earn something by occasional part-time work, and this together with his father’s pension enabled them to exist without starving and without burdening others. He told the magistrate about his father, explained that it would be impossible for him to work full time, and started job hunting.

While he was about this, he was subjected to a physical and a psychiatric examination. The psychiatrists declared him sane, but the medical commission reported that he was incapable of heavy labor. He had a congenitally weak heart, had been excused from the draft because of it, and now the doctors’ verdict gave him hope. But just as he had found suitable work as a librarian, he was seized, taken to the prosecutor, and thrown into jail.

For the next two weeks until his trial, he was kept on a starvation diet in unheated cells. His apartment was searched, his pictures and manuscripts confiscated (most of these were later returned, but not his seventeenth-century icons, which were appropriated by some official who knew their monetary value), and he had to undergo another psychiatric examination and endure two sessions with the judge. A new charge, pornography, had been brought against him, though it was soon dropped thanks to the judgment of “the literary consultant of the Komsomol theater,” to whom his plays—unpublished and unproduced—were submitted in manuscript for expert opinion: she declared that the definition of “pornography” was unclear to her, and that, furthermore, the plays were “interesting” and something like Brecht’s.

Advertisement

But the judge, in an interview on the eve of the trial, told Amalrik that he had read his plays and found them “anti-Soviet,” a serious charge, as Amalrik explains: “In our country this is not just a description of a political attitude but a legal term used to define actions and utterances punishable by prison sentences of up to seven years.”

It was clear that his case had been prejudged. And the trial, as might have been expected, turned out to be a farce.

The judge “behaved less like a judge than a prosecutor,” intimidated witnesses, refused to admit evidence that would have disproved certain vital particulars in the list of accusations, dwelt irrelevantly on the “anti-Soviet” plays, and “devoted most of his time to the expression of his own opinion on literature and art.” At the end, Amalrik was convicted of having “systematically avoided socially useful work” for many years and sentenced to two and a half years’ resettlement with “obligatory physical labor.”

In crowded railroad cars, through filthy transit jails, Amalrik was transported, in a journey that took almost a month, to Guryevka, a village in Siberia, and made to work there in a kolkhoz, that is, a communal farm. He dug pits for electric-cable poles, pitched hay, cleaned barns, grazed cattle, hauled bags of flax, carted straw, shoveled manure, transported water, delivered milk. The work was exhausting and unremitting, and there was neither adequate clothing, fuel, nor shelter. The inhabitants were stupid, barbaric, profane, and drunken.

Early in October, having received a wire that his father was seriously ill, Amalrik obtained a short leave, but by the time he reached Moscow, his father had died. This death provoked him to a rarely outspoken expression of bitterness. “I very much wanted to write objectively,” he says in a Foreword. “If I have not altogether succeeded in this and if here and there a note of irritation slips through, I am very sorry about it.” The “note of irritation” about his father’s death hardly calls for forgiveness: “He would not have died if I had not been sent away or if he had at least had some guarantee that he could be looked after until I returned. In effect he was killed by Judge Chigrinov and the sort of attitude Chigrinov represented.”

In Moscow Amalrik saw again a girl he had met just before his trial “and liked very much.” He asked her to marry him; she consented, and breaking with her bigoted Tartar family, followed him into exile where she endured with him the cold and hunger of a Siberian winter, and was then forced to leave, because objections were raised to her living in the village without official registration. Since to register would have meant forfeiting forever the right to live in Moscow, they decided to part, but staved off the day as long as possible on every conceivable pretext. At last on the 8th of March they said good-by, “not knowing when we should see each other again.” Guyzel (or Giselle) is as courageous, independent, and determined a person as Andrei, an artist whose work cannot be exhibited in Russia, just as her husband’s cannot be published there.

Amalrik knew that as a reward for good behavior, his sentence might be shortened. And he behaved. But relief came sooner than he had expected. Through the persistent efforts of his friend Aleksandr Ginzburg, his case was appealed and overturned by the Supreme Court on the 20th of June. The evidence was still to be reexamined by the prosecutor’s office, but on July 8, he received a telegram that read: “Sentence reversed. Official notice follows by letter. Drinks on you. Ginzburg.” (Six months later, on the 23rd of January, 1967, Ginzburg was arrested for compiling and circulating a White Book on the trials of Sinyavsky and Daniel, and sentenced to five years’ hard labor.)

Amalrik returned to Moscow and after a prolonged altercation with the bureaucracy, received a permit to live there. His narrative closes with the mockingly triumphant announcement of his new address: “City of Moscow, 5th Police Precinct. Registered for permanent residence at 5 Vakhtangov Street, Apartment 5. November 2, 1966,” and the remark: “With this the story of my exile comes to an end.” It is dated “1966-1967, Guryevka-Moscow.”

But this was not the end of persecution. On May 7, 1969, his new apartment was searched, an occasion that has been vividly described by two American journalists, the bureau chief of The New York Times, Henry Kamm, in his Preface to Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984? and by Anatole Shub, Moscow correspondent of the Washington Post, who was soon to be expelled from Russia for writing “anti-Soviet” articles. Mr. Shub quotes his wife’s account of the visit:3

Advertisement

Their books and papers and records were strewn all over the floor. Giselle was by the window, all white with large frightened eyes. Seated at the desk was a stranger writing, and behind Giselle was another man, half-smiling. Leaning on the piano were two dirty, sullen thugs.

I propelled myself toward her and kissed her on the cheek. “What’s the matter?” She just looked around and said nothing. Andrei put his arms around her shoulders….

It seems, however, they were not seized at this time, and the following month Amalrik finished his 1984, which he sent to The Alexander Herzen Foundation in Amsterdam. It was received there on July 4 and published, in Russian, in November. (This appropriately named foundation was established last year for the express purpose of publishing work censored in the Soviet Union, and “will gladly go out of business,” according to its chief, Professor Karel von het Reve, “on the day” this censorship is lifted.)4 Last May the Amalriks were arrested, and about three months ago, on July 28, William Cole, another correspondent who has been ejected from the Soviet Union, reported on a CBS program that they had been taken to Sverdlovsk, where presumably they were awaiting trial—in a provincial city it would attract less attention than in Moscow or Leningrad—and, quite possibly, might never be heard of again.

Sverdlovsk contains a transit jail in which Amalrik spent ten days on his way to Siberia: “I had never seen anything as oppressive as this; the cell was between twenty and thirty square yards in size and it was crammed with people. There was a fearful stench. The door was made of thick iron bars, like the entrance to a cage in the zoo; this was in order to keep the room ventilated.” There he encountered some very pathetic prisoners. “One of them, who looked like a fairly well-educated person, lay silently on his bunk all the time, scarcely ever speaking to anyone. This was the first time he had run away and when I asked him why, he said: ‘If you get to a kolkhoz, you’ll run away too.’ When I asked him what he would do when they took him back, he said tonelessly that he would run away again.” And there was “a boy of about sixteen with a completely crazed expression on his face. He was going to be tried for stealing a bicycle. He walked up and down all the time muttering incoherently to himself.”

Amalrik’s narrative is filled with such vignettes as these—touching, comic, revolting, never fanciful or sentimental. His writing is economical and straightforward, and his story achieves something he had not intended, an engaging self-portrait that emerges through its unemphatic lines, the portrait of a fearless, outspoken, idealistic man. But its distinguishing quality is intellectual, an ability to perceive and analyze the general significance of what he has himself lived through. Tolerant, unprejudiced, deeply committed to the principles of individual rights, audacious but by no means fanatical, Amalrik examines what he sees with his sharp intelligence and a hard logic that lend weight to his opinions.

He points to flaws in the Soviet penal and judicial system: Article 70 of the Criminal Code, for example, which imposes severe penalties for “anti-Soviet” agitation and propaganda is “an obvious violation” of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech, press, and assembly; the rules which forbid a prisoner to return to his former place of residence make it almost impossible for him to get work and only increase the incidence of crime; unreasonable penalties create a kind of “duel between hopeless despair and senseless cruelty”; propagandist trials and vindictive sentences destroy respect for law. His paramount concern, however, is the moral attitudes of men, the presuppositions that determine their behavior, and it is these that lead him to the gloomy prediction that by 1984 the Soviet Union will collapse into utter chaos. The trickery and boorishness he saw in Moscow, the dull and dismal ignorance, malice, and inefficiency he had to live with in Siberia, the gross inhumanity and crass indifference in both places were symptomatic of all Russia, a land of hopelessness and cynicism, in which men live in perfect disregard for the rights and the wellbeing of others.

As I see it [Amalrik writes in 1984], no idea can ever be put into practice if it is not understood by the majority of the people. Whether because of its historical traditions or for some other reason, the idea of self-government, of equality before the law and of personal freedom—and the responsibility that goes with these—are almost completely incomprehensible to the Russian people…. To the majority of the people the very word “freedom” is synonymous with “disorder”…it is preposterous to the popular mind that the human personality should represent any kind of value…. In Russian history man has always been a means and never in any sense an end.

This central point in his argument is fortified by everything he has observed in the course of his harsh experience: in the ways laws are administered and in the laws themselves; in the attitudes of men toward their government and toward one another, and the opinions they express. Indifference or despair is prevalent everywhere. In the kolkhoz, villagers and exiles labored unwillingly to the point of exhaustion, always angry, irritated, abusive. Their houses and barns were jerry-built and no one thought of repairing them; roofs leaked and collapsed; in the cowsheds calves froze in their mothers’ wombs; silage was carted great distances in the dead of winter, the horses falling on the ice; water was hauled in buckets; laboriously collected manure was never used as fertilizer; hay was raked and pitched by hand.

When Amalrik suggested simple improvements, “the kolkhozniks just dismissed me with a wave of the hand: things had always been this way and they didn’t need to be told their business….” Amalrik concludes that “their reluctance to make things easier for themselves” is due to a profoundly ingrained slave mentality: “they have been taught to think that their job is simply to obey orders.” They complain bitterly about their life but when asked “how they would like to live…reply ‘What other life is there?’ ” In effect, they are “totally without rights,” living under a system of “forced labor…. They have no right to move except to another kolkhoz; their identity papers are kept at the kolkhoz office and never handed to them.”

Their existence is excessively dull, they have neither pride nor interest in their work, their only distraction is drink. And their state of mind, far from being unusual, is characteristic of Russians as a whole. Students, Amalrik discovered, “held almost Stalinist views,” asserting that “a strong man like Stalin was needed to keep everyone in hand.” “Unfortunately,” he comments, “the idea that nothing can be achieved except by force and coercion is deeply rooted in the Russian people.”

This is why in his 1984 essay, Amalrik holds out so little hope for the Soviet Union and wishes to correct the Western notion that things are getting better there because repressive measures are being openly opposed. In recent years, trial after trial, each one accompanied by protesting letters and demonstrations, has come to public attention: the cases of Josif Brodsky in 1964, of Sinyavsky and Daniel in 1965, of Ginzburg in 1967, of Pavel Litvinov in 1968, etc. 5 Amalrik does not deny that a Democratic Movement, aiming at “the rule of law based on the rights of man,” exists in the USSR. But he has doubts about its efficacy, weakened as it is by “a cult of its own impotence” and the inability even of its enlightened members to dissociate themselves from the State as the ultimate administrator and employer. Even dissidents cannot think of themselves as other than servants of the State, so that their remonstrances have “the character of the dissatisfaction of a junior clerk with the attitude of his superior.”

“Reasonable changes,” which in the naïve assumption of the West are bound to take place, are possible only “where life is based fundamentally, even if only partially, on reasonable foundations.” In the Soviet Union, life is not so based and Russian history “has by no means been a continuous victory of reason.” If there is now a pretense to legality where absolute tyranny used to be the rule, this is but show, a thin surface above almost universal and unassailable depravity, of general moral lassitude and the unconscious acquiescence in a form of government that is inhuman and irrational at the core.

Meliorism will not do. A cataclysmic reversal of values is required, based on the kind of visceral disgust with despotism of which Amalrik once spoke to Henry Kamm: “I was against the system when I was a child…. My protest is…organic…I am against the system not because it is dishonest but from organic revulsion.” This is very far from the Rousseauistic postulates of such nineteenth-century rebels as Tolstoy, who insisted on the innate virtues of the “unspoiled” muzhik, and very far too from Dostoevsky’s depth psychology. Nor is Amalrik befuddled by a sentimental attachment to the Russian land and the “Russian soul.” Looking at the Soviet Union from the perspective of history, he sees his countrymen not as creatures mystically endowed with special ethnic qualities but as human beings whose basic attitudes have been forged in an almost continuous process of oppression, of which the present system is the latest phase. His severe strictures are neither treachery nor disloyalty to his country; they are an idealist’s bitter aversion toward a system that destroys or perverts those precious attributes of human decency—justice, reason, tolerance—in which he has a passionate faith and which he does not consider impossible to men. Although “organic revulsion” as such is not necessarily fruitful, it may, when directed toward reason by a vigorous intelligence and a heroic will, result in the kind of brilliant discourse on the human condition which Amalrik has produced.

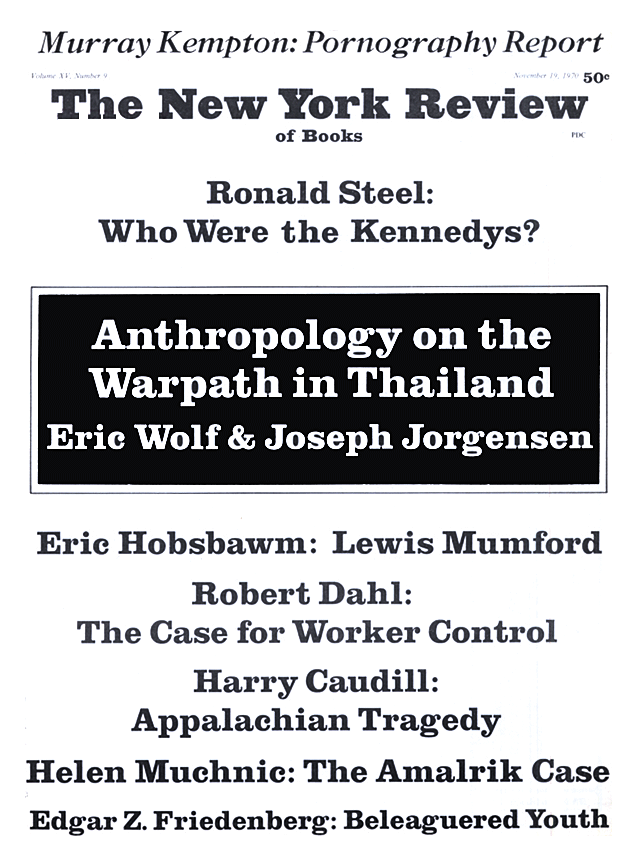

This Issue

November 19, 1970

-

1

Reviewed by Neal Ascherson, NYR, April 23, 1970. ↩

-

2

Vid. Harold J. Berman, Soviet Criminal Law and Procedure, Harvard, 1966, pp. 9-11, where the differences between this and other administrative laws are analyzed. ↩

-

3

In his book, The New Russian Tragedy, Norton, 1969. ↩

-

4

The New York Times, July 2, 1970. ↩

-

5

An impressive collection of documents in these cases has been recently published: In Quest of Justice: Protest and Dissent in the Soviet Union Today, edited by Abraham Brumberg. Praeger, 1970. ↩