“Thus on the fateful banks of Nile,

Weeps the deceitful crocodile!“

Rosmersholm is one of Ibsen’s best plays. The heroine, Rebecca West, is torn apart by high motive and low passion, by ugly necessity and splendid hopes, in a manner of the greatest dramatic and psychological interest. The play has Ibsen’s usual atmosphere of a petty social constriction. Coldness and the bitterest heats of feeling fight miserably with each other. In the background there are dirty politics and cowardly conventionality, but the essential action, the backward and forward movement of the plot, lies in the character and the competitive struggle between the two women.

When the play opens, the wife, Beata Rosmer, is dead by suicide, and Rosmer is left with the agent of the suicide, Rebecca West. The wife’s memory hovers about them, but her lingering is not of the sentimental kind, although the rather cozy mourners at first like to pretend that such is the case. In truth, the dead wife is the peculiar center of a harsh and demeaning power struggle. “It was like a fight to the death between Beata and me,” Rebecca finally confesses. The play will now proceed through revelations and changes to an ending that is not quite satisfactory on the plane of probability. Rebecca and Rosmer are free, but they are led by the turns of their inward and outward circumstances to clasp hands and go the way of the wife, to death in the rushing waters of the mill stream. This closes the circle too neatly; it is extreme and unnecessarily corporeal for a drama that is moral and psychological.

Gross experience tells us that Rosmer and Rebecca will find a way to do as they please. The dead are gone; whatever advantages the empty space may provide are likely to be swiftly occupied by the living. And yet the triangular struggle between the two women has been so fierce and primitive, the terms of it finally so futile and empty, that we follow Ibsen right up to the mill bridge, even if we do not concede the plunge into the waters. Perhaps Parson Rosmer, with his finicky, unsteady grip on things, but not Rebecca West, who has been formed by the forces of necessity and will, traits that do not easily lend themselves to the suicidal resolution. Still, Rebecca has unusual self-understanding and it is this that ruins her victory. “The dead woman has taken them,” the housekeeper says. That may be true, but only in an oblique sense. Disgust, futility, the final inadequacy of Rosmer are the devastating powers. The psychology of the play is at every point original and disturbing. The turns and shifts of consequence are bleak, unexpected, but true to feeling.

It is Ibsen’s genius to place the ruthlessness of women beside the vanity and self-love of men. In a love triangle both are necessary; these are the conditions, the grounds upon which the battle will be fought. Without the heightened sense of importance a man naturally acquires when he is the object of the possessive determinations of two women, nothing interesting could happen. If he were quickly to choose one over the other, the dramatic reverberations would be slight, even rather indolent; the triangle demands his cooperation in the humiliation of one, along with some period of pretense, suffering, uncertainty.

In Rosmersholm the husband is unusually dense and mild and leans as long as he can on the stick of “friendship” and “innocence.” The aging architect in The Master Builder is more straightforward. The willful, destructive Hilda attaches herself to him for a bit of sadistic teasing which the tormented, failing man is too vain to suspect. He has been, up to her entrance, busy trying to emasculate his younger competitors. Solness is, as Shaw says, “a very fascinating man whom nobody, himself least of all, could suspect of having shot his bolt and being already dead.” The architect’s wife, Mrs. Solness, is dejection and depression itself, immobilized gloom, supposedly sacrificed to her husband’s career. (This we are not obliged to agree with, since she is one of those who seem born to downness.) “Higher and higher!” calls the awful young girl. She waves her white shawl at the giddy architect who has scaled the rafters and he falls to his death.

In Rosmersholm, Rebecca has come down from the North. This freezing land of harshness and deprivation leaves its mark on the spirit. There one learns the lessons of life. (In An Enemy of the People, Dr. Stockmann remembers his span of service in the North with fear and it is only the strength of moral conviction that allows him to put his present, more hopeful, circumstances in jeopardy and perhaps face a return to the cold, isolated region.) Rebecca is thirty. She is intelligent, emancipated, idealistic. Her youth has both tarnished and hardened her. She is probably the illegitimate daughter of the Dr. West who adopted her but did not offer her any special kindness.

Advertisement

Rebecca is in a dangerous state. She is free—or, rather, adrift. She is immensely needy, looking desperately for some place to land, to live. And what can that mean? It means she must have a husband, and soon. What else can she hope for? Heaven is not very likely to send a desperate, strong-willed woman of thirty an interesting, unmarried man. No, it will send her someone’s husband and tell her to dispose of the wife as best she can. Wives accommodate because they invariably have their faults and their glaring lacks. These are transformed into moral issues and the defeat of deficiency becomes something of a crusade. Thus in righteousness is the hurdle vaulted.

The Rosmer family is a solid one and somehow Rebecca attaches herself to it. Mrs. Rosmer, Beata, becomes fond of her and invites her to settle on their estate. Mrs. Solness, in The Master Builder, does not rise with enthusiasm at the sight of Hilda with her knapsack and alpenstock, but even she agrees to find a place for her. The torpid life at Rosmersholm and at the villa of the Solness family is such that these additions are electrifying to the husbands, and not altogether unwelcomed by the wives. For change, vitality, everyone is willing to take the risk. This, once more, is a measure of the closeness of life in Ibsen’s plays, the repetitive frustration of it, the oppressiveness of provincial attitude and society.

At Rosmersholm there is stagnation, but Rebecca soon sees little corners and cracks where inspiration might creep in. She sets about overthrowing what she decides to be, in Shaw’s words, “the extinguishing effect” of Mrs. Rosmer. During her residence she calmly works at altering and liberalizing the views of Rosmer, who had been previously a parson and is now struggling with unorthodoxy. Rebecca does not try to brighten the conventional attitudes of Mrs. Rosmer, although there seems every possibility that, with a certain amount of effort, the sun of idealism might have been welcomed there also. The intellectual excitement—a genuine part of Rebecca’s nature—has the most stimulating and happy effect on Parson Rosmer. He is still prudish and needs the blanket of high intentions to cover their growing love, to make it appear to himself “good” rather than “bad.”

Beata Rosmer is sensitive and highstrung. She is well aware of the way things are going, and where they will inevitably end. When the play opens Beata has already committed suicide. She has jumped into the churning waters under the mill bridge. Rosmer and Rebecca have had a year of quiet mourning, and if Rosmer still can’t bring himself to walk over the bridge, there is no doubt that he is quite well, very much alive, and not inclined to vex himself with blame for his wife’s suicide.

We learn about Beata’s life and death gradually, as the play unfolds. In a tangled, small-town tussle over ideas, religion, and politics, the state of mind that led to Beata’s self-destruction is gradually revealed. Her suffering had been immensely complicated, made up of jealousy, genuine love for her husband, and an early, numbing sense of defeat and helplessness in the contest with Rebecca. Beata had become so nervous and distraught that the lovers decided her mind had failed and this had been the more or less accepted view of her suicide, although there were those in town who had what everywhere are known as “their own ideas.”

A year has passed since the death and things might have gone along well, except that in a political and theological dispute in the town points are scored against Rosmer by the revealing of a secret suicide letter in which Beata had absolved Rosmer and Rebecca of all blame for her self-destruction. Naturally you cannot be absolved of something you are not accused or suspected of. Rosmer is forced by the absolution to connect Beata’s sufferings with actions of his own. It is at this point that the psychological depth of the play is most moving. In the most brilliant shifts of feeling, the sadness and waste of the triangle begin to rot the relationship between Rosmer and Rebecca. Rebecca makes an astonishing confession. She acknowledges her ruthless humiliation of the wife. “I wanted to get rid of Beata, one way or another. But I never really imagined it would happen. Every little step I risked, every faltering advance, I seemed to hear something call out within me: ‘No further. Not a step further!’… And yet I could not stop!”

Advertisement

This is the dead center of the play. Rebecca’s self-knowledge lifts her far above the selfish teasing of Hilda, but it is worse also because she is older, better, more valuable in every way. She has committed one of Strindberg’s “psychic murders,” a horrible one with a real body washed up on the shore. What else could she do? She did it to live. Rebecca’s will and necessity crushed Beata. Rosmer, and the possession of him, had become the possession of an important, life-enhancing commodity. The ethic of the struggle had been the business ethic—no ethic at all, except the advantage of profit. The parson is willed to change hands like a corporation, with the old, outmoded group being cast aside and the new liberal management quietly installed. At the opening of the play, we see Rebecca placing flowers about the drawing room, a nicety Beata never cared much for. Rosmer is shifting from the conservative to the liberal side on local issues. Those newly in charge are making changes.

When Beata was still alive she had ceased to be a person for the lovers and had become a mere negative… Things couldn’t go forward when she was about, and what a wonderful force the parson might be if it were not for the drag of the past… But this is not at all true. It is self-interest that drives Rebecca and darting, smug self-satisfaction that allows Rosmer to pretend nothing is happening.

As the facts unfold, the rightness and sureness of Ibsen’s sense of the contest never falter. First, the lovers deny Beata any participation in their interests and ideas. She is excluded on the grounds of her past dampening effect upon the advance of skeptical thinking within the household. We can imagine they would change the subject when Beata joined them and begin to talk of trivial, tiresome things or fall into bored silence. We are not sure that Beata was unworthy to help along the new day. She was fearful, but then she had sized up the importance of fresh ideas to Rebecca. Rosmer’s sexual timidity, his need for innocence did not leave any other path open. Secondly, Rosmer took as proof of his wife’s insanity the fact that she had hysterical fits of passion for him, threw herself at him.

What can you do with a man like that? Of course, Beata was on the right track. Fear and rejection had told her all she needed to know. She saw that Rebecca meant to “have” him; they had closed their feelings to any claims of her own and it was all confused in her poor husband’s mind with radicalism, atheism, and a delightful new friendship. Beata’s character and her predicament, as it comes to us from the description of others, make her a plausible possibility for suicide. Rebecca’s ruthlessness and Rosmer’s dimness are an overwhelming force.

But in Ibsen things are never simple. When Rosmer at last faces his wife’s jealousy, her anguish over his love for Rebecca, these new conditions, this new understanding of his own past, have the most peculiar effect upon him. He is immediately caught up in a fascination, even a sort of triumphant admiration of his wife’s suffering! With a sudden flood of imaginative comprehension he puts himself in her place, goes through every step of her agony. “Oh, what a battle she must have fought! And alone too, Rebecca; desperate and quite alone!—and then, at last, this heart-breaking, accusing victory in the mill race!” He is deeply impressed by the ultimate quality of her love, by the grandeur of her sacrifice of her own life. What can compare with this? he asks himself.

Rebecca urges him to forget the dead, to live, to move away from the past. But it is no use. Rosmer now announces himself fascinated by destruction, not by life. He and Rebecca have moved into darkness. They have begun to distrust and to dislike each other. Ashes are in their throats. Rosmer is frightened of Rebecca and in a Norwegian madness of his own asks her to match Beata’s love. Together they throw themselves in the mill stream. Even if the suicide is not entirely convincing, there is no life left in their love. But they do not die from guilt, but from the uselessness of it all, from the emptiness, from self-hatred.

What had Rosmer meant to Rebecca? She had the notion that she could, through him, accomplish a self-definition impossible by her own efforts. One would have to agree that in her situation and time this bright, penniless orphan could scarcely hope to enter history unattended. Her plans for an enlargement of views, for free-thinking joyousness and life-giving openness are merely longings of her personal temperament that have been ground into dust by poverty, lack of connections, the absence of any security or hope. What good does it do her to be a “new woman” until she has properly settled herself somewhere? And where is that to be if not at Rosmersholm?

Rebecca must, it seems, manipulate someone or fall by the wayside. Her flirtation, even her exploitation of Rosmer would not trouble us—if only there weren’t the wife. Beata is something like Nora’s children. Sacrifices on certain terms disturb us. Rebecca’s motives are, by force of circumstance, always paradoxical; fineness of spirit is mixed with the coarse determination to appropriate Rosmer, to sweep away his past obligations, to win out over someone else. It is a futility and harshness upon which nothing grand can be built.

What does Rosmer offer? He offers, most of all, comfort—and that is the bare truth of him. He is well-to-do, respected, has a margin of possibility because of his “ancient stock,” and his pliable nature—a general eligibility. There, alone at Rosmersholm, with Beata out of the way, he and Rebecca would side with the liberals, slough off clerical repressions, bring in flowers and light, gracefully question the traditions: this would be the good life as Rebecca imagines it. If she doesn’t “get” Rosmer, what will she do? She knows what lies ahead. She has not been asleep all these thirty years, and instead has a “past”—a miserable, dead love affair that gave her nothing. She must seize Rosmer and his acres. The element of absolute necessity gives her situation a strongly vital and insistent aspect.

Still the lack of scruple is large and the consequences are ugly. Rebecca fights to the very end. When Rosmer begins to sink into his peculiar remorse she faces him with a direct question: Would you bring Beata back? Rosmer demurs, not able to accept the clarity and honesty of the challenge.

There is always something vulgar about a triangle. Even in the most elevated circumstances, the struggle is one of consumption, of “having” or “getting” something that is not, so to speak, on the free market. The victors are degraded by slyness, corruption, and greediness; the loser by weakness and humiliation. Heartlessness, ignobility, and ambition are the essence. It is a struggle for the experienced, not for the very young. Only those who have lived and endured have the understanding of the narrowness of opportunity within one lifetime. This experience provides the energy and the brutal decisiveness necessary to persist.

The critic A. C. Bradley, who has the most radiant appreciation of the love of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, nevertheless notes that Octavia, whom Antony married for reasons of political advantage, is wisely left in the shadows. “We resent his [Antony’s] treatment of Octavia, whom Shakespeare was obliged to leave a mere sketch, lest our feeling for the hero and heroine should be too much chilled.” Indeed every triangle is lowly and has, in the end, a diminishing effect upon the dignity of the man, just as it diminishes the moral life of the women.

Isn’t Rosmer just a bit comic? He has been turned into an object by Beata and Rebecca. Observers on the sideline see everything about him that is hidden to himself, especially his fertile justifications. Vanity, boastfulness, emotional pomposity infect his thoughts and actions. He cannot in the end be taken seriously and this above all makes the bitter battle for possession stupid and ugly. After it is over, Rosmer will inevitably be overcome by a suspicion that something has happened to him he had not expected. Is he loved for himself? the object will finally wonder, just as the heiress is aware of the commercial value of her decisions. Am I worth dying for? the conscience luxuriously asks. The answer is No. Soon, all the joy—they have called it here the “innocence”—has gone out of the future. Rosmer is sensibly filled with fear of the conquering woman. Where did her ruthlessness come from? Has it died away forever, or is it only lying hidden for the moment?

Now he remembers that there was something large, exceptional, splendid about Beata’s love. Why should he forget Beata’s devotion to him and live completely in the new present? A love like that is an example, if nothing else, to the next one, a judgment, a comparison. It can be used.

We cannot help but sympathize with Rebecca because of her intelligence, her gift for life and the unjust cramp of her circumstances. We are sad that she requires an object and a victim. Rebecca is not vicious like Hedda Gabler, but she is not devoted like Thea, either. Why shouldn’t she have attached her idealism to the wavering conscience of Mortengaard, a newspaperman trying to pull up from unfortunate mistakes? After all it has been said of Rosmer that “he never laughs.” No, in Finmark she has known the hazards of disgrace and dependency too closely to have energy left for such extensive reclamations. Also, there is everything attractive, graceful, and promising about her. She wants the stage setting of her life to correspond to these possibilities. The question of her own birth likewise inclines her toward the power of the long accumulations of the Rosmer family. Rebecca is too exposed to be a bohemian and a crusader, she wants to be a patrician liberal.

The terms of a triangle are always exaggerated and distorted and its excitement is temporary. We know it will one day be settled; someone will give way, give up, step aside, die. When it does, letdown and questioning poison the victory. A struggle between two men for a single woman is a somewhat different construction. The man would rather not have a predecessor; the necessity of winning and displacing is irksome and degrading. How much better were she fresh, free, the fields unplowed. It is only the strength of desire that enables him to endure the embarrassment. There is even the sense that some natural bond with other men, a bond of fellowship or domination, has been broken. A woman, however, is not always sorry that there should be an open battle; if she wins it is a mark of her own powers, an achievement, a triumph. She expects to fight her way, for how could it be otherwise? Through him she is to live and no price is too high.

One feels that Vronsky, for all his love of Anna, would soon have backed away if she had not made their affair possible. But she is determined and so he tries to believe, with Antony, that “The nobleness of life is to do thus.” Vronsky tells himself that only the old-fashioned disapprove of his conduct. He even gets his ideas into line and because of the irregularity of his situation with Anna, “he has become a partisan of every sort of progress.” Earlier, Vronsky allowed himself to think that Karenin was “a superfluous and tiresome person. No doubt he was in a pitiable position, but how could that be helped?” Inside Vronsky knows that he too is in a pitiable position and he does not care for it. But he is trapped by love and Anna’s obsession, as Rosmer will finally see that Rebecca’s need was a trap.

The conflict in Rosmersholm is an active one. The three people are discovering each other, creating and destroying. This is, many feel, its own justification and morality. The characters are helpless in the face of a spontaneous happening that only slowly turns into a matter of possession and dispossession, ownership and loss. This is different from the deceit in The Wings of the Dove. Kate Croy and Densher are pure commercial principle without innocence or illusion, and so are Osmond and Madame Merle in The Portrait of a Lady. These are sad, capitalist lyrics, ending on the dying note of all triangles: “We shall never be again as we were.”

Ibsen withholds full approval and sympathy for Rebecca, just as Tolstoy withholds it from Anna. They do not believe women should live by the will, accountable only to desire. The heroines become distorted, destructive; a strange hysterical emptiness begins to cut them off from natural feelings. When Anna has a child by Vronsky she finds that “however hard she tried, she could not love this little child, and to feign love was beyond her powers.” The kind of love she has for Vronsky is outside the scope of family life—for that even Karenin is better.

When Rebecca agrees to kill herself in the mill stream it is not expiation but a furious disappointment in Rosmer and disgust with herself. Rosmer is perhaps ready for death since he has fallen back in love with Beata, or with her love for him. Ibsen once said in explanation of Rosmersholm: “Conscience is very conservative.” The trembling, uncertain fascination Ibsen felt in the struggle between the two women is the power of the play. He did not quite trust Rebecca and had himself experienced women of her sort. True, he was, as Archer describes him, short-sighted, of low stature, peering, thin-lipped, with a mouth “depressed at the corners into a curve indicative of an iron will.”

No matter—he was also one of the most famous men in Europe and a particular excitement to girls and women in Germany, Vienna, and Scandinavia. “Miss B. is totally mad for Mr. I.,” and “Miss B. is grief-stricken.” Miss B. (Emilie Bardach) was eighteen and Mr. I. was sixty-one. He knew how determined poor thirty-year-old, brilliant Rebecca could be, and how inanely tempting the Nordic siren, Hilda. But his plays are written out of suspicion, not infatuation. And perhaps that is why he understood so brutally the pathetic false hopes of the heroines that by possession and appropriation they would possess themselves. In that way there is a radical undercurrent to the realistic plays. If they have any moral it is that, in the end, nothing will turn out to have been worth the destruction of others and of oneself.

(This is the last of three articles on Ibsen and women.)

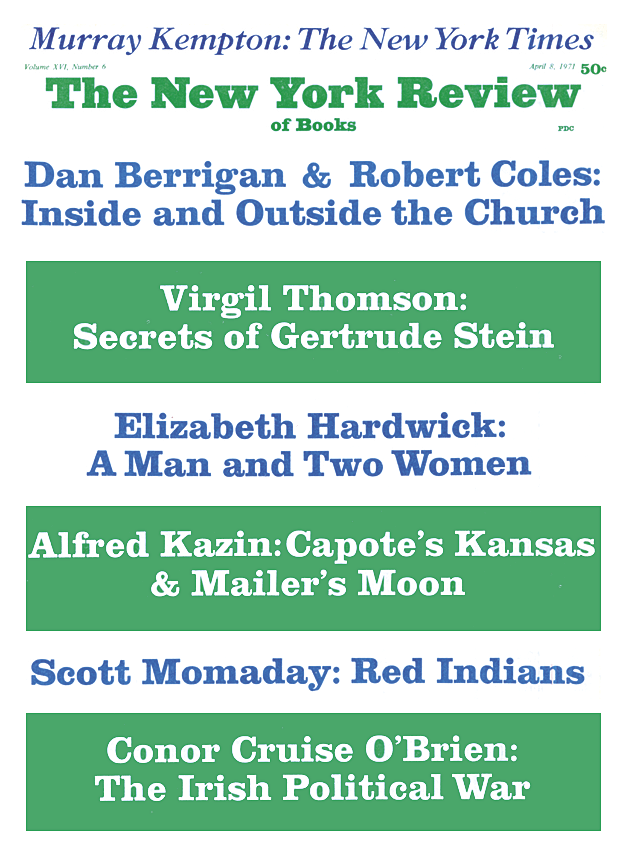

This Issue

April 8, 1971