What are the roots that clutch American fiction? Nearly 150 years ago, William Hazlitt seized a gist—or at any rate what an Englishman repeatedly returns to as a gist. No roots; stony rubbish?

The map of America is not historical; and therefore, works of fiction do not take root in it; for the fiction, to be good for anything, must not be in the author’s mind, but belong to the age or country in which he lives. The genius of America is essentially mechanical and modern.

Hence the bulging impotence of Charles Brockden Brown:

His strength and his efforts are convulsive throes—his works are a banquet of horrors. They are full (to disease) of imagination—but it is forced, violent, and shocking. This is to be expected, we apprehend, in attempts of this kind in a country like America, where there is, generally speaking, no natural imagination. The mind must be excited by overstraining, by pulleys and levers.

American fiction is still haunted by the Specter of the Brockden. Such Gothic comics as Jerome Charyn’s novel Eisenhower, My Eisenhower and Paul Spike’s stories Bad News: these hope that all roads of excess lead to the palace of wisdom. For that truly difficult thing, a historical map, they substitute that falsely easy one, a futurist fantasy. They exult in the Americanness of the essentially mechanical and modern; they yank the pulleys and levers. They can never sup too full of horrors; they gag on without gagging. They manifest no natural imagination, but rather a hardened childishness.

Two far better books, those by Cecil Dawkins and Tess Slesinger, constitute more intelligent conceptions of the genius of America. Helped perhaps by the gross mannishness of the mechanical and modern, the male manipulating of these pulleys and levers, American women novelists have mostly reflected a truer terror whether in past or present. In The Live Goat, Miss Dawkins merges history and horror in the story—set in about 1840—of a half-witted boy who has murdered a sixteen-year-old girl and who is brought back hundreds of miles to be hanged. Natural imagination is here sustained by a rich imagining of nature—lost landscapes of jungle plethora and of silky swamp. Instead of a future-mongering, we are given the pertinacity of the past—one which insists on how much of the genius of America is other than mechanical and modern. The horrors are not banqueted upon.

Nor are they in Miss Slesinger’s stories, On Being Told That Her Second Husband Has Taken His First Lover. Horrors not as a banquet but as canapés. Sterility and chatter, anger and void, not the lurid livid flickerings which elsewhere stir a comfortable Disneyesque terror. Miss Slesinger’s stories were originally published in 1935 as Time: The Present; scarcely any of them have dated at all, and they make their present felt. They know the guilts of intellectuality and of padded comfort, of affluence and of fluency, and they offer no flashy torture chamber but instead a keen sense of an American plight, of what it is to be stretched on the rack of a too easy chair. Moreover they despise despair.

The dignity of The Live Goat is a matter of its lucid refusal to claim that it can enter the head or heart of its idiot boy Isaac. There is no question that he killed the girl; and almost certainly he killed her because he knew that on this day, her wedding day, she was to leave. But that “almost certainly” preserves a proper privacy; the girl’s father is willing to grant that Isaac in some sense killed her for love, but we are aware of the honorable desperation that makes him so much want to grant that (makes it then not a reluctant granting but a needed comfort), so that “in some sense” is not blurred into sentimentality but is left as a stricken blank. Isaac is heroic in his suffering trudge, and proud in his ultimate moments of refusal (to set his knees; to eat when it is forced upon him; to be driven back into his village rather than to walk in on ruined feet). Yet such heroism and such pride can be gazed upon but scarcely entered into.

The book is markedly unsentimental; the code which pursues Isaac for 500 miles, which halters him and brings him back, and which hangs him, is presented with a very precise sense of what in it is high and proud, and what is gross and vengeful. If this is not what should be done (and yes, a great deal cries out against it), what then should be done? The book’s world is sufficiently confident and expansive to enable such a question to be taken seriously, that is, implicitly; it offers not the pleasures of excoriation (how dare they?), but the urgencies of concern (dare they—would you dare in any such circumstances?—do other?). Unlike the Gothic comics, The Live Goat is independent of the servile wish to write something which one’s allegiant friends could not possibly misconstrue or misrepresent. It is not concerned to placate but to implicate. What do we want now that we know that we do not want this “primitive” code? Incarceration; exile; “cure”; the electric chair; ignoring and averting of eyes?

Advertisement

There is pathos and humility in the moment when the girl’s father tells Isaac to stand up so that he can be hanged: “We all heard Eustace say, ‘Stand up, will you, son.”‘ “Son” there is a kindness and a truth (and not just a pressing insistence on Abraham and Isaac, or an existential proposition); as in all affecting fiction, the pathos and humility are not daubed upon the character by the book, but rather seep into the book from the freely imagined character’s magnanimity. The book stands for a moment in awe of this person it has imagined.

But there are the wrong kinds of awe, and The Live Goat is badly bedeviled by two of its characters. The preaching Hite and the philosophical Tuckahoe: these—with whom the author imagines herself to be in intimate and revealing contact, since speech is after all very much their language—remain alien, garrulous, and blockish. Which means that the book’s largest pretensions, theological-philosophical, stand unfulfilled. But one is left with a narrative which, in both senses, moves. One, moreover, which humanely eschews the jaded pleasures of a chase. Left, too, with the vividly fearful, as in the episodes of the quicksand and of the crocodiles. All effected through a variety of styles—an interweaving of internal monologues from everyone save Isaac—which never (well, hardly ever) become ventriloquism or pastiche, but which can range from meticulous shock to tender gravity. There is the ominous imaginability of the honeyed landscape:

I have the gift of defining the time of day from the thickness of yellow in the light. Deny me sight of sun and shade, I could nonetheless give you the time, by the thickness of yellow in the light. Shadows stretch fingers toward us from the wood. High over the trees the shabby scavengers ride air shafts so thick with yellow, thick with stench, they needn’t work their wings to stay aloft.

There is the pity-struck unimaginability of Isaac’s pain:

An inch of rag, all that’s left of his stocking, still circles his leg above the ankle. Emile is staring at what you wouldn’t call a foot if you didn’t know it to be one, not minding the brogan. But me, I’ve had to turn from the sight. I look instead at the brogan upside down in Emile’s hand. A sickening stuff—part blood, part pus, part river—strings out of it. Make myself look at the foot and try to judge his pain by what just the sight of it gives me, but I’ve hit on an impossible measure. Ankle speckled blue with dirt, what looks like mud but might be blood clotted about the nails, too long, curled down over the ends of his toes like claws. Then see the sole—hanging in shreds slug-shaped, slug-white, shriveled from the swash, but the new blood startling red. The circle wounds from the brogan’s bared nails look like the mark of ringworm, but under the skin the palest yellow of trapped pus. I never seen nothing like it. Never seen nothing like him—how he’d of had to separate hisself from his body to walk that way, lifting a bed of nails each time he lifts his foot, and setting it down again under him.

Miss Slesinger’s stories inhabit and people a world of terror, the limbo of neither/nor. A world where guilt hopes to find itself reduced to sheepishness. There is the neither/nor of intellectuals who are uncreative: “‘Funny ones,’ class-straddlers, intellectuals, tight-rope-walking somewhere in the middle.” And of the school housekeeper, with “her tragedy of being neither servant nor teacher.” Of the adolescents at Magnolia Hall, neither children nor women. Of the teachers there, “the funny teachers, neither young nor old, neither girls nor women, neither women nor ladies—but falling somewhere in those categories, between the students and the Duchess.”

And there is the man who is not exactly employed or unemployed, but taken on by the department store for the Christmas rush and with the faint hope that…. The woman of the title who is neither securely within her marriage nor securely without it (her second husband), but left to be gruesomely plucky in the limbo of his confessed ongoing goings-on. The receptionist who loves the boss but is not yet his lover. The intellectual who has had an abortion and now sees herself as “a creature who could not be a woman and could not be a man.” The old lady who is an importunate, lavish hostess to literary men, but who does not so much fill a void as create one with her unrespected, interfering professional generosity. The young wife who wanders between her mother’s unintelligent warmth and her husband’s intelligent coldness. The token blacks in the liberal white school.

Advertisement

To list such varieties of limbo is to make Miss Slesinger’s stories sound more obsessive and less ranging than they are; her preoccupations are diversely insistent. And the possibility of something other than sterility is always there; it is not a simple or cheap irony which is directed upon the head-mistress’s favorite lines from Long-fellow, on Maidenhood: “Standing with reluctant feet / Where the brook and river meet.”

It is unhappiness that elicits Miss Slesinger’s felicities. “The copy-writers had left their partitioned desks and were standing in a tentative group about the switchboard, behind which Gracie looked very small and frightened, wearing her telephone wreath like a crown of electric thorns.” The tone precludes both a deflating sneer and an inflating allegorizing. The tact permits of condescension neither to her characters nor to her readers; symbolism is so lightly touched as to leave the right doubt whether symbolism is the right word. One thinks of the unobtrusive relationship between the dead baby and the father’s nervous gestures: “Miles had taken off his glasses; passed his hand tiredly across his eyes; was sucking now as though he expected relief, some answer, on the tortoise-shell curve which wound around his ear.” Or of the cool hints that we should attend to a great deal more than the simply physical as we watch the laden young wife open the door of her newish home:

Katherine could not bear to drop a single one of her burdens, now that she had come so far; she made a series of supreme efforts, balancing, juggling, squirming, forcing her key out of her glove with fractional, inch-worm motions, still carefully separating the bottle of milk from the package of Best Eggs, evoking a new muscle to keep the small package from slipping.

Like all good writers, Miss Slesinger evokes new muscles. They effect much more than do pulleys and levers.

“Surrounded by creams and vials, I tested my homemade G-string / jock-strap, stretching the little black pouch, stuffed my testicles inside, and made sure my tail didn’t show.” The first page of Eisenhower, My Eisenhower stirred a sleeping memory, and when mention was later made of “gypsy heaven” the memory awoke. Of course, Blinkie Heaven:

“It’s this blinkie burlesque joint,” Suzanne said, laughing in a carefree, extraverted way, “where the strippers all have horrible faces, only of course the fellow who M.C.s the show builds them up as raving beauties. Go on, Irving.” “Well…it’s just when the girl with the biggest squint and the most acne is taking off her G-string that the hero gets his sight back, and naturally he’s got everything—soup-stain sweater, Screw You White Man glasses, transparent pants….”

As imagined by Kingsley Amis, in One Fat Englishman. He imagined the reviews, too: “Perhaps one of the four most poised and authoritative contributions of the New York neo-Gothic meta-fantasy school”—Times Literary Supplement. Since 1963, to make matters worse, there has been Giles Goat-Boy. The publishers of Eisenhower are brazen: “Charyn has created a world as original and outrageous as the one that John Barth made in Giles Goat-Boy.” Setting aside the question of whether Barth’s book was original or floggedly fatigued, was outrageous or “outrageous” (that is, richly academically complaisant), we may still ask whether two Giles Goat-Boys aren’t more than—how many more than?—enough.

Eisenhower is a pullulating puerile neo-Gothic meta-fantasy about political oppression, with the gypsies as the oppressed minority; a fantasy tarted out with meant-to-be-suggestive parallels (to Vietnam, to the Black Panthers), and with the pricey gratuitousness of physical grotesquerie thrown in—these gypsies have a horny tail so that Mr. Charyn can strain out more sex jokes. (” ‘Toby fuck me with your tail.’ ‘Can’t, sweetheart. It’s inflamed today.’ “)

It would be a pity to call all this surrealist, since surrealism has been characterized by wit, dignity, precision, and stoicism, whereas Eisenhower is freewheeling dealing. This is the dead end of the sick joke, all ingratiation and winking and cultural know-how. “Scoochbin-Scriabin would remove a wooden lath from his medical box, insert it in Bam’s anus, twist until Bam volunteered to be a Yankee agent.” The thrilled little hope is that in the ambiance of all this daring heartlessness no one will actually notice the mindlessness and witlessness. A man might write such stuff forever, if he would abandon his mindlessness to it. The odds are that the heartlessness, at least, is not an affectation.

The comic recipe is as frantically, stalely new as are the marketing men’s chocolate bars which it smugly mocks. Mr. Charyn knows that some things are so good for a laugh that one is relieved of any necessity to make new true jokes about them. Oh, things like Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Scout Law and advertisements. And acronyms—who else would have seen the exultant possibilities of POOP? Potential Officers’ Orientation Program. And discordant names, like Sacheverel Glom and Nathan Bumpo Muss. And audacious experimentalisms, like freakily tweakily incorporating “a statistical history of Dolph Barookioon’s major and minor league career,” and a spoof Who’s Who entry. And trudging flights of fancy, like that Toby has to be pumped up with a bicycle pump and it won’t last twenty-four hours. And linguistic caprices (Zdarunee nooshkee, droogu). And much petit guignol, including a torture chamber which uses a kiddie car. And a very great deal of oral sex. And all so glumly willed that one could scream, or something. Instance:

Dame Margarite Candelabra, syndicated columnist and Ministress of Culture, who judged the Toothberry jingles, reproached the chancellor for keeping me, dragged me to a corner, burped and screamed when she found out I was left-handed (which isn’t uncommon with gypsies of my generation), apologized for her rudeness, and kissed me on the left ear. She was bosomless and smelled of sweat and roses. Her fingers hovered elfishly between my buttocks and my fly.

Less odious than the fingers that hovered elfishly over the typewriter.

Bad News has the same bad habits, including “that fine oral sex.” Literature, Pound-wise, is news that stays news; Bad News is avant-garde of yesteryear, and therefore—even before we might ask about staying power—is no news. Paul Spike shares too many confidences with Jerome Charyn. He, too, is weeningly confident that acronyms cannot but slay us: “Dowler Rene was a trustee of EAT: Exterminate All Trouble.” Confident, again, that provided your credentials are impeccably leftishly zany, then ethnic jokes are once again more than permissible, they are de rigueur. (Amis pounced on that squalid bluff, too.) Radical chi-chi. “It was a classified piece on student coalitions with the Epileptic Movement and especially the dealings of a terrorist outfit called the Helping Hand of Jesus.”

Mr. Spike, as hungry for a laugh cue as any media wag, knows a fecund callousness when he comes up with one, so his Epileptics are ubiquitous. “Recently, rioters had taken over an entire section of the country. Led by two Senators and an Epileptic, they were in complete control of Nebraska, Missouri, and Kansas.” And again: “How he is going to do depends on how he handles the Epileptic problem.”

I don’t think much of, or because of, Mr. Spike’s jokes. “Are you sure these are real priests, Felix?” “They drink like fish and their socks smell, so I figure they are.” Funny names are resorted to, as when we are expected to delight in “an olive Universe Blazer designed by Jaime de la Hunky of Alicante and London.” It would be puritanical to think that the power of jokes is commensurate to some intrinsic recalcitrance (not but what Mr. Spike, like Mr. Charyn, is grindingly puritanical), yet is there not something effortlessly pointless and freezingly easy about making up a character called A.B. Dick so that one may then surface with this craven wager? “He wondered where was A.B. Dick now. Living up to his name, he bet.”

Bad News, again like Eisenhower, limps where it should spring. It sprains its brains and even so all it can manage by way of world-curdling is that clans of giant apes have emerged from Loch Ness, are taking over Scotland, and eat money. Nothing is then done with this hobbledehoy bright idea, fortunately. But there is the usual programmatically casual callousness (light-years after Evelyn Waugh). “Got a message for you,” says Billy.

“All right then, shoot,” said Gordon. But one of his lieutenants, one Immanuel, misunderstood and fired fifteen big slugs out of his scatter gun. The black souvenir jacket was suddenly a delta full of blood rivers. Billy was sobbing through his death pain. Gordon couldn’t believe the dumb mistake and slapped his forehead, then pulled an orange dart off his belt and jabbed it into this Immanuel’s chest. A super nausea dart always fatal after two days of paralysis and seizure.

Is there much point in halfheartedly making up a featherbrained girl so that we can scorn her diary? “In the afternoon he showed me how to deep-sea fish but I didn’t catch a thing. He caught two sharks. Yuk.” And yet there is even less point—though a great deal of slighted poignancy—in jeering (manlily, of course) at “Box 456” and her love ad. That little story shakes with laughter at its own crude joke, but its joke is too near the real things which are not jokes at all—or at any rate are not such as to give Mr. Spike such lordly joking rights. As usual, his imagination precipitates not, as he had hoped, a super nausea dart, but a mere yuk.

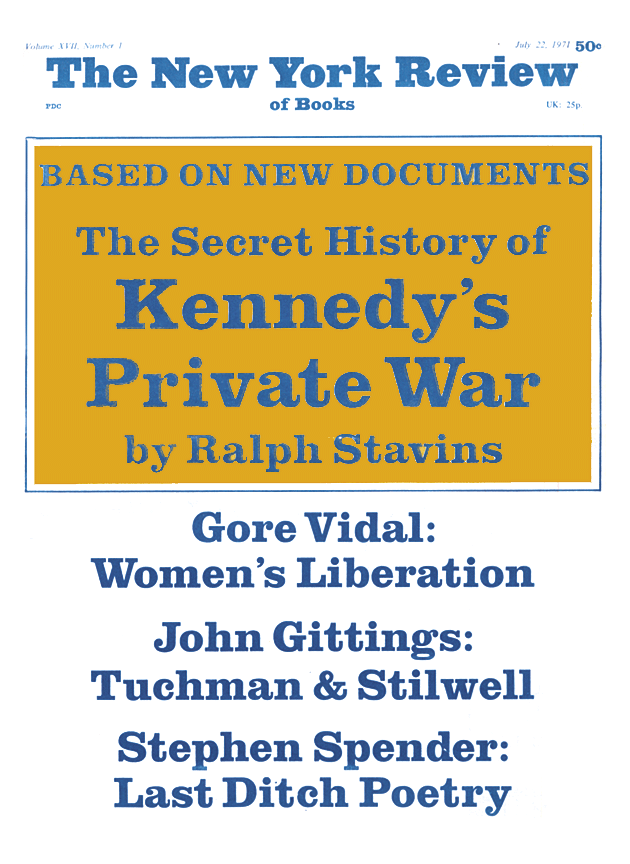

This Issue

July 22, 1971