Herbert Butterfield noticed in the early Charles James Fox an uncontrollable itch to add “the final strokes to the argument of his friends, as though determined to drive the whole logic of the situation to a further extreme—to go one note higher than the top note of the piano.”1 This observation seems unjust to Fox, whose life is our best argument for the social uses of demagoguery; but it does perfectly describe Joseph R. McCarthy, our strongest recent argument against them.

That image may also explain why no very helpful assessment of what got itself called the Age of McCarthy is possible unless we get the figure of Joe McCarthy as far from center stage as we can. The enormities of the musician who abuses the piano have a way of obscuring the disharmonies of the score which was appointed as entirely appropriate for him to play. Over-attendance upon the excessive can distract us from noticing how bad the normal is.

All three of the works under review come from younger historians whose perspective across fifteen years ought to give us some hope that they can hold McCarthy in just proportion. The first two do not quite succeed. Mr. Griffith seems indeed to suffer a fixation very like the one that used to afflict so many of us who were his seniors at the time: the generation of children which was truly traumatized by that ogre’s face on television may only now be reaching the age to instruct us.

Mr. Harper does better, since his study of Mr. Truman’s Loyalty and Security Program begins five years before most of us ever heard of Joe McCarthy. Even so, McCarthy’s first two years of fame occupy as much space in The Politics of Loyalty as the five which preceded them; and the figure of Mr. Truman, shadowed—to put it delicately—through the first and second acts, is enabled to complete the third in the blinding light of his defiance of the Beast, those having been times that required the blackest of villains before their heroes could be redeemed.

Mr. Theoharis, on the other hand, has so escaped the pieties and sentimentalities of the Fifties as to offer them nothing kinder than a withering smile. Our desire to have the period’s characters rendered in their proper proportions could hardly be better satisfied. McCarthy is relegated in this composition to the place and comparative dimensions of one of Veronese’s dwarfs, since it is Mr. Theoharis’s judgment that Mr. Truman set the tone of the national possession by fear of the Communist danger and that McCarthyism was only Trumanism carried to its logical conclusion.

His argument is not without weaknesses; but none of them seriously affects its essential strength. He has successfully, if not always gracefully, closed the question of major blame. Still, one finds oneself wishing that Mr. Theoharis’s eye for documents were as busy as his head for judgments. There is a deficiency of sustaining data here; one ends not entirely trusting the material underpinning the assertion. He has that low opinion of the motives of public men which should commend itself to other historians; but it leads him to assert reasons for their actions more often suppositious than is comfortable. Having seen the matter whole, Mr. Theoharis does not bother as much as he should about light and shadow. Curiously the fruits of Mr. Harper’s hunt through the Truman library files tend to support Mr. Theoharis’s thesis rather better than Theoharis’s researches do.

And, then, it seems too easy for Theoharis to blame the cold war and the national assumption of American omnipotence so entirely on Mr. Truman’s ability to infect the population with his own fantasies. Mr. Theoharis is very stubborn in his refusal to notice that we had come through years when the figure of Adolph Hitler—who does not remember the movies of the Hollywood Ten?—had given many of us the habit of thinking of wars as pitting Light against Darkness, and that it was not simple-minded to see Joseph Stalin as not altogether different. Mr. Theoharis’s thesis would be in no way damaged, and his argument closer to precision, if he recognized that the 1948 Stalinist coup in Czechoslovakia did at least as much to harden attitudes and to arouse alarms as the Hiss-Chambers case. One does not redress the balance by lifting a weight placed too heavily on one side and setting it on the other.

Still, if Mr. Theoharis overlooks some of the things the Fifties saw, he sees many more of the things the Fifties overlooked; and his argument that Mr. Truman was more to blame than any other American for the excesses of the time survives so powerfully that it deserves to be sketched in some detail—with its bones Mr. Theoharis’s and its flesh Mr. Harper’s.

Advertisement

Mr. Truman’s course was set in November of 1946 when he established his Temporary Commission on Employee Loyalty. Its inspirations were various but powerful—the passions of his Justice Department’s permanent party; a successful Republican Congressional campaign to a degree founded on the issue of internal subversion; and the alarms of the Gouzenko and the Amerasia cases.2

The Loyalty Commission’s membership included representatives of the Civil Service Commission and of the Departments of State, Treasury, War, Navy, and Justice. Justice, War, and Navy were the dominant chorus, with a few ineffectual bleats of caution from State and Treasury.

The Temporary Loyalty Commission’s chairman was Assistant Attorney General A. Devitt (Gus) Vanech, who had equipped himself for engaging this sensitive subject through years in the Land Division. Vanech, Harper tells us, persisted “in the debatable line that the presidential mandate required the commission to assume the problem, not to study it.” This guiding assumption was set forth in Attorney General Tom Clark’s testimony to the commission on January 23, 1947, when he appeared, as an example of hierarchical values, as a substitute for J. Edgar Hoover:

I do not believe [Clark said] that the gravity of the problem should be weighed in the light of numbers, but rather from the view of the serious threat which even one disloyal person constitutes to the security of the United States government.

That premise so controlled the first draft of the commission’s report, as circulated on January 28, 1947, that, says Harper, its “estimate of the seriousness of the loyalty issue rested entirely on a letter presented by the FBI…and couched in the most general terms,” apparently because Justice was so suspicious of the ambassadors from State and Treasury that it feared to trust them with any detailed information about the size and character of the FBI’s file on subversives. The draft report also cited with emphatic approval the conclusion of the House of Representatives Committee on Civil Service “that all doubts relative to employee loyalty should be resolved in favor of the government.” The objections of what may be called the civilian departments produced some moderation in the final language, but did nothing to alter the basic philosophy.

The initiation of the loyalty program happened, moreover, at a turn in Mr. Truman’s foreign policy where he felt a need, not merely spiritual but also tactical, to rely on the devil theory of Communism. He had decided, in the late winter of 1947, that he would have to take over Great Britain’s place as shield against Communism in Greece; while searching for ways to justify such a risk, he sought the advice of Arthur Vandenburg, the only Republican paladin he could entirely trust in the Senate. Vandenburg’s counsel was that Mr. Truman “had to scare hell out of the country.”

The President acted so manfully upon this instruction that, when the Truman Doctrine was enunciated, the enemy was flatly identified as the Soviet Union and the national duty as desperate resistance to the gravest peril, not only in Greece but everywhere.

Mr. Theoharis provides us some clangorous chords that thereafter seemed to Mr. Truman entirely proper for the piano:

We must not be confused about the issue which confronts the world today…. It is tyranny or freedom…. And even worse, communism denies the very existence of God. Religion is persecuted because it stands for freedom under God. This threat to our liberty and to our faith must be faced by each one of us. [President Truman, Saint Patrick’s Day, 1948]

We must beware of those who are devoting themselves to sowing the seeds of disunity among our people…. We must not fall victim to the insidious propaganda that peace can be obtained solely by wanting peace. This theory is advanced in the hope that it will deceive our people and that we will permit our strength to dwindle…. [President Truman, St. Patrick’s Day, 1948]

Our homes, our Nation, all the things we believe in, are in great danger. [President Truman, 1951]

The forces that are most anxious to weaken our internal security are not always easy to identify. Communists have been trained to deceit and secretly work towards the day when they hope to replace our American way of life with a Communist dictatorship. They utilize cleverly camouflaged movements, such as some peace groups and civil rights organizations, to achieve their sinister purposes. While they as individuals are difficult to identify—the Communist Party line is clear. Its first concern is the advancement of Soviet Russia and the Godless Communist cause. It is important to learn to know the enemies of the American way of life. [Department of Justice press release, July, 1950]

There are today many Communists in America. They are everywhere—in factories, offices, butcher shops, on street corners, in private business—and each carries in himself the germs of death for society. [Attorney General McGrath, April, 1950]

All the tempests of the score—the image of a godlessness more dangerous than tyranny; the threat of an alien presence everywhere; the reiterated warning that no stranger, however innocent his countenance, could be trusted—had thus been sounded by the Truman Administration before McCarthy began abusing the piano.

Advertisement

Mr. Theoharis is convinced that, with these hyperbolic utterances, the President and his assistants succeeded in thoroughly alarming the American people about their peril. This assertion is his weakest point, depending as its evidence does on the confusions and contradictions of public opinion polls. We can concede Mr. Truman’s intention to alarm without necessarily granting its achievement. Historians can make the mistake, once they have proved that a speech was made, of going on to the assumption that many people paid it much attention.

For example, what are we to make of the findings Mr. Theoharis offers us from the polls reported in Public Opinion Quarterly?

In April, 1947, 18 per cent [of one sample] believed American Communists were loyal to the United States….

Mr. Truman then opened up all the stops on the anti-Communist theme and, nine months later when he was in full blast,

In December, 1947, 19 per cent of one sample believed American Communists were loyal to the United States….

Opinion polls, whatever the mood of the times when they are taken, seldom encourage anyone’s faith in public support of the goal of equal justice under law. Still, in 1947, Public Opinion Quarterly could report that 19 percent of one sample thought that “Communists have the same rights as other citizens.” A polling team could hardly have found that proportion of minds unclosed in any poll of public officials even that early in the affair.

“In early 1948,” Mr. Theoharis says, and fairly enough, “neither Truman nor HUAC [the House Committee on Un-American Activities] distinguished between simple Communist party membership and the intent to commit treason. Truman’s defense of individual liberties centered on the loyal and unfairly accused; he thus implicitly accepted the need to deal vigorously with the disloyal.”3

Even in the spring of 1947, when the flames were only just beginning to flick at the green wood, Mr. Truman was plainly alarmed enough to judge that security overrode any concerns about the liberty of his servants. In establishing his Loyalty Review Board Mr. Truman was, Mr. Harper finds, “obviously advised that public confidence in the program would be stimulated by appointing as its supervisors conservatives, men in no way associated with the administration.”

The problem was plainly to avoid placing any identifiable “liberals” in charge of the loyalty operations. This was a major concession to the fanatical anti-Communists in the battle for public support.

Seth Richardson, the first chairman of the Loyalty Review Board, so entirely fit this prescription that, shortly after he took office in March of 1947, he could express the belief that “the government is entitled to discharge any employee for reasons which seem sufficient to the government and without extending to such employee any hearing whatsoever.” Throughout his tenure, Richardson seems to have regarded the program’s procedures in granting the suspect employee a hearing as a handsome concession rather than a recognition of right. In December, 1948, he reminded an Assistant Secretary of the Interior that suspicion ought to be permanent and that ” ‘some misgivings’ might properly be entertained in respect to employees who had been cleared after investigation.” Richardson was hardly the sort of presiding officer to whom complaints about the cruelties and inanities of his regional loyalty boards might hopefully be carried.

In the spring of 1951, President Truman was himself disturbed enough by reports of injustice in the conduct of the regional loyalty boards that he asked Charles Murphy, his Special Counsel, to find some way “to put a stop to their un-American activities.” The history of this intervention by the Commander-in-Chief is instructive:

The President wrote Murphy in May of 1951. In July of 1951, after consulting Murphy, Mr. Truman ordered the National Security Council to investigate the workings of the Government Employee Security Program. The NSC did not reply with its findings until April of 1952, nearly a year after the President first became aroused over the injustices of the procedure.

The National Security Council’s report was made after an investigation that was at least deliberate if not thorough. While the Council asserted that it had found no individual employee who had been wronged by any agency decision about his loyalty, it did note the appearance of some defects in the program, among them “charges…too vague to permit an intelligent defense”; occasional coercion of employees to resign; too hasty suspensions; and blacklisting of persons found to be security risks even by nonsensitive agencies. A procedure of that sort would have to be awfully lucky if it did not at some point commit an injustice to some individual somewhere. But Mr. Truman had the comfort of being assured that the NSC had found none. He nonetheless set about improvements; but, Mr. Harper tells us,

The reforms incident upon this report had not unfortunately been completed before the Truman administration left office, to be replaced by a regime far more prone to pursue the phantom of absolute security.

Mr. Harper, who is otherwise most serviceable in matters of detail, does not tell us the particulars of any reforms that had been commenced even nineteen months after Mr. Truman had asked for them, which omission gives us reason to doubt that there were many.

In any case, whatever the degree to which the excesses of the loyalty program may have pained Mr. Truman by its fourth year, it seems to have been pure balm to him in its first. The House Committee on Un-American Activities, appeased, turned its attention in 1947 from subversion in government to Communism in Hollywood. In 1948, Clark Clifford, orchestrator of Mr. Truman’s campaign themes, could look upon what seemed to everyone else the darkling plain of the 1948 elections and offer his commander the consolation that he was free at least of the Red-baiters, because he had “stolen their thunder by initiating his own government employee loyalty procedure.”

Mr. Truman was so much the anti-Communist candidate that William F. Batt, the American Veterans Committee’s legate to the Research Division of the American Veterans Committee, could even hear a report that Thomas E. Dewey planned to discharge J. Edgar Hoover and pass it on to the White House as a splendid chance for the President to express public support of his FBI director and “put himself and Hoover on the side of the angels.”4

But the Hiss-Chambers case had already commenced and the fall of China completed the destruction of Mr. Truman’s sanctuary. By the time Senator McCarthy burst into the hunt in 1950, his was only the loudest yawp in a pack that had been teeming since 1949.

How did he run so far? Michael Rogin has already disposed of the theory that McCarthy’s public following represented some really substantial populist rebellion against an elite of managers.5 “It is tempting,” Rogin has said, “to explain the hysteria with which McCarthy infected the country by the hysterical preoccupations of the masses of people. But the masses did not levy an attack on their political leaders; the attack was made by one section of the political elite against another.”

The most general misconception in assessments of McCarthyism has been, as Rogin says, “to underestimate [McCarthy’s] roots in an already existing conservative faction inside the GOP—a faction even more concerned about Communism, the cold war and Korea than was the country as a whole.” But we can at least suspect that the rival elite, Mr. Truman’s own establishment, was also more concerned about Communism and the cold war than the country as a whole. The common people get blamed for everything that goes wrong; yet there are noticeable ways in which they conducted themselves rather better than any of our elites during the McCarthy period.

Certainly the more malignant cruelties against Communists in the Fifties were committed largely by persons whose position and education ought to have allowed us to expect more civility from them than from any of their social inferiors. Very few of my own friends who were Communists and victims at the time reported any mean actions by their neighbors. On the contrary there were touching examples of kindness: in one case, the daughter of Saul Wellman, a Communist functionary, was given the American Legion’s Americanism medal when she was graduated from a Detroit junior high school in 1957, while her father had been convicted of violating the Smith Act and her mother was facing deportation.

Even nine years later, it could still be celebrated as a mark of Robert Kennedy’s progress beyond the norm for politicians that he most temperately objected when the Communist Robert Thompson, a winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, was refused burial in the Arlington National Cemetery. The awareness of danger which often inflates that danger in the imagination is far more vivid in Washington than in most other places and may explain why right-wing ideas have always been more persuasive to so many of our leaders than they have ever lastingly been to most other people. As Rogin points out, President Eisenhower was always substantially more popular than McCarthy, and very probably because the public thought of Mr. Eisenhower as a moderate.

So in the capital at least, the atmosphere which McCarthy is presumed to have poisoned was already pretty toxic when he made his clamorous appearance in West Virginia on Lincoln Day of 1950. The minority caucus in the Senate was, with Vandenburg out of service, entirely under the control of the Taft Republicans; and the venomous Senator Pat McCarran was a major power among the Democrats. Mr. Truman’s own authority had been substantially diminished by the China reversal and by aspects of his own personality which Mr. Theoharis uniquely and convincingly perceives.

Mr. Truman, he argues, was, for all his populist surface, very much an elitist in his operations as a governor:

Truman deemed international politics too complex for the average citizen; only experts, he felt could understand and properly respond to international developments. In fact, because he felt that mass opinion was made up of limited understanding on the one hand and undue idealism on the other, he considered it as little more than a minor obstacle to carrying out his policies…. As Truman viewed things, in both international and domestic politics, the NATO countries, Congress and the public existed to ratify decisions, not to take part in their formation.

It was this bent which had directed Mr. Truman to present his Greek and Turkish policies in a rhetoric so heightened as to make anyone who might want soberly to debate them seem indifferent to the country’s very safety. He justified withholding details of his policies from Congress on grounds of national security; but it is hard to believe, after Mr. Theoharis’s book, that his refusal to make public the Yalta agreements had any purpose except to avoid public embarrassment. Those of us who have had the advantage of seeing one consequence of this course finally in the Vietnam war may have more sympathy than we could then have expected with Senator Taft’s rage at this posture of Mr. Truman’s and come to grant him at least the excuse of frustration when he welcomed McCarthy, if only as pig in the minefields.

As for Mr. Truman, being as thorough a partisan as Senator Taft, he could only judge McCarthy as a Republican instrument, a partner in one of those combinations of Blifil and Black George familiar in our legislative history. We may indeed see in his partisanship against McCarthy the origin of that passion for individual liberty which began infecting the President’s utterances without much intruding upon his policies. He was too used to thinking of politics as a game of musical chairs to resist leaping for the chair marked Freedom when the Republicans had taken the chair of Repression.

Still these flights of libertarian rhetoric seemed to the President of so little practical use in engaging the McCarthy challenge that he suspended them in favor of asserting and trying to prove that he was a better, since less careless, anti-Communist than any of his critics. His position toward Senator McCarthy seems in retrospect very little different from that of Vice President Nixon when, in 1954 with the McCarthy scourge upon President Eisenhower too, he argued that, when shooting rats, it is best to use a rifle because a scattergun might injure non-rats.

When McCarthy charged the State Department with harboring Communists, Mr. Truman’s first response was to encourage the Senate to appoint a committee to examine McCarthy’s evidence and discredit him by exposing how paltry it was. These sanitary duties were placed in the charge of Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland, chairman of the Armed Services Committee, who had every quality a representative of the Senate establishment needs except the existence of an undivided establishment. Tydings began confronting the challenge with the requisite prejudice; and his committee’s July, 1950, report dismissed McCarthy with a scorn that would likely have disposed of him if it had represented the authority of a united Senate.

But that fine arrogance of Senator Tydings, crushing if it had been the arrogance of the whole body, became inadequate pretense when it was revealed as the expression only of its Democratic caucus. The Republican Blifils on Tydings’s subcommittee so well protected their Black George as to produce a judgment against him supported by nothing more impressive than a straight party line vote. McCarthy was enabled therefore to lurch into the 1950 Congressional campaign soiled by no more than a partisan condemnation, that is, essentially unsoiled. Tydings was defeated after, if not because of, McCarthy’s intervention in the Maryland Senatorial campaign; so were a number of other Democratic Senate paladins; and Tydings’s remains and theirs would serve at least two years to support the illusion of their surviving colleagues that to resist McCarthy was to be left with one’s bones bleaching.

Mr. Truman’s campaign against McCarthy in the 1950 elections had seldom risen above the insistence that, by dividing the country, the senator from Wisconsin was proving himself the best agent the Kremlin had in the United States. This argument having failed, Mr. Truman could only attempt to remedy the reverses of 1950 with the device which had diverted the pre-McCarthyites after the reverses of 1956: he would strengthen and improve his Employee Loyalty Program. In other words, he would try the Seth Richardson shift again.

And so, in January of 1951, he announced the establishment of a Presidential Commission on Internal Security and Individual Rights. When Herbert Hoover declined, Admiral Chester B. Nimitz was established as chairman; his fellow commissioners, while worthy enough, were generally inferior in public prestige to those totems who had been approached and had begged off in the preliminary canvass.

The 1951 commission was never able to function because Senator McCarran contemptuously refused to clear its members from that exemption from conflict-of-interest statutes which is customarily a routine concession to members of temporary Presidential commissions.

Still Harper makes it clear how little was lost to Individual Rights, that afterthought to the priority of Internal Security, when the commission failed of survival. Its only action, prior to extinction, was to approve a February, 1951, request by the permanent Loyalty Review Board that “the basic loyalty standard be changed from ‘reasonable grounds’ to suspect disloyalty to ‘reasonable doubt’ about an employee’s loyalty.” The Nimitz Commission’s solitary exercise of its mandate to balance internal security with individual liberty was to shift from the loyalty board to the employee the duty of establishing his innocence beyond reasonable doubt and thus to add substantially to his burdens.

But that action only conformed to the dreary pattern of a history where every challenge to liberty was heroically confronted by some desperate effort to eliminate a fancied weakness in security.

When the Mundt-Nixon Internal Security Act was proceeding toward passage in May of 1950, Attorney General McGrath could conceive no way to deflect its supporters except with especially Draconian amendments to the Foreign Agents Registration Act. McGrath was resisted in this diversion by Stephen Spingarn, the White House administrative assistant who was affectionately described by Charles Murphy as “our one-man civil liberties bureau.” Yet even Spingarn was reduced to arguing for measures that would make restrictions of liberty worse as the only practical way of avoiding others that would make them irretrievably worse.

In July of 1950, Spingarn offered his own answer to the Mundt-Nixon bill:

My proposal is that legislation be added requiring registration with the Department of Justice of all “subversive organizations” (i.e. both the right-wing and left-wing subversive groups), and the furnishing by them to the Department of Justice of pertinent information about themselves and specifically the details about the size and source of their revenues and the recipients of their expenditures…. To any serious counter-intelligence organization, legislation (such as I propose)…would be of far more value than all the superpatriot provisions of the Mundt-Nixon bill, even overlooking the fact that that bill goes far beyond the concept of individual rights in a democratic state.

There may be those who, without blinking at the political necessities of the time, wonder how well the concepts of individual rights in a democratic state could be served by forcing private citizens hostile to a government to provide it with reports on their activities that would list names of supporters, sources of funds, and other intimacies about themselves for no purpose except to assist that government in its counterintelligence efforts against them.

The liberal Senate Democrats felt similarly impelled to advocate bad measures in hopes of forestalling worse ones. In September, 1950, when the Mundt-Nixon had become the McCarran Bill, Senators Douglas, Humphrey, and Lehman sponsored a substitute which Mr. Griffith describes as “an emergency detention plan for the internment of suspected subversives upon the declaration of an ‘internal security emergency’ by the President.” Senator Lehman’s administrative assistant explained to his principal that it was a “very bad bill” which would set aside all rights to habeas corpus; but it would “certainly impress the public with the fact that you are determined to act against communists.”

Senator Lehman needed, to be sure, to temper his normally gallant fervor because he was running for re-election in New York State that year. And there were dangers even here; his administrative assistant warned, if only facetiously, that Governor Dewey might use the senator’s support of the detention bill to show “that you are really more of a fascist than he is.”

And so Senator McCarthy continued his ravages through the Democratic era, little inconvenienced by a resistance flawed in moral sensibility and insufficiently recognizable as an alternative because its anti-Communist rhetoric did not often enough appear all that different from his own. Whatever doubts may have occasionally troubled Mr. Truman about the contribution of his own excesses to the atmosphere in which McCarthy swelled, he in general continued them; and, granting his respect for the military and his fidelity to the devil theory of Communism, we could hardly have expected him to do otherwise. Nor, the mold having been set, can we justly complain that he could have changed it if he had tried.

In 1953, a Republican President took Mr. Truman’s place; and Senator McCarthy went to the abyss, impelled there mainly by his own impulse and assisted, in moments of hesitation on the path, by a series of delicate nudges from President Eisenhower.

Mr. Griffith provides us with the chronicle of McCarthy’s fall in most workmanlike fashion, omitting few of the less appetizing details of its management, although the job would have been better if he had omitted fewer. He ends up kinder to the anti-McCarthy coalition than every one of its elements deserves; and that tolerance prevents him from explaining as much about its deficiencies as his industry suggests he has come to understand:

1) He does not make it clear enough that any outsider must expect to suffer any abuse within the power of an officeholder; and this particular habit of government ought to be noticed even when its victim is as undeserving an outsider as Joe McCarthy. Mr. Griffith, for example, offers a most grisly account of the torments which McCarthy inflicted upon the Senate subcommittee that struggled to investigate his finances and his campaign conduct in the fall of 1950. But he almost studiously neglects to mention that this same committee, in its zeal to beat back this foe of liberty, had put a mail watch on all first-class letters addressed to McCarthy at his home from October 24 to November 16, 1952. Throughout this period, at the direction of one senator, the Washington post office provided a list of the names and addresses of the senders and the postmarks of all letters delivered to the home of another.

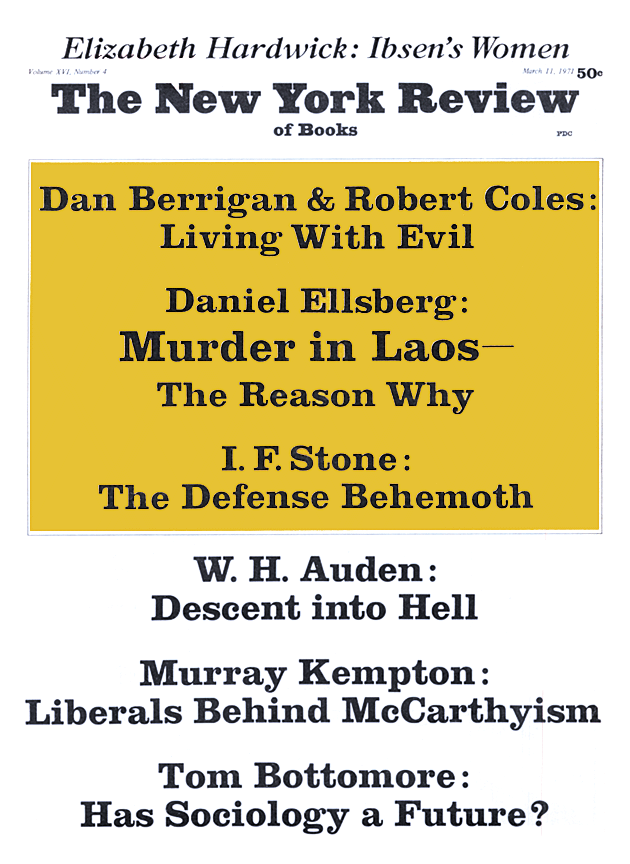

2) Mr. Griffith has favored us with a good deal of material about the character and the rhetoric of the campaign against McCarthy which helps our understanding of how little his fall changed the fundamentals of government policy. But, again, Mr. Griffith fails to report things he certainly knows. He contributes an affectionate and useful study of Senator Ralph Flanders, the Vermont Republican, who in March of 1954 delivered the first direct assault on McCarthy to come from his own party’s side of the aisle. But his quotations from Flanders’s speech nowhere suggest elements in its tone which led I.F. Stone to select it as a notable example of how hard it was “to draw the line of principle between McCarthy and his critics.”6

All the fighters against McCarthyism [Stone noticed] are impelled to adopt its premises…. Flanders talked of a crisis “in the age long warfare between God and the Devil for the souls of men.” He spoke of Italy as “ready to fall into Communist hands,” of Britain nibbling at “the drugged bait of trade profits.”… Flanders told the Senate, “We will be left with no place to trade and no place to go except as we are permitted to trade and go by the Communist masters of the world.”

We ought to encourage historians never to undertake a study of the Fifties without strenuous attention to I.F. Stone; it is only one reason for such advice that the essential premises of Flanders’s attack on McCarthy probably survive for our enlightenment in Stone’s book but in no other works in print.

After all, Stone asked, “If there is indeed a monstrous and diabolic conspiracy against world peace, isn’t McCarthy right?”

3) Griffith does not tell us enough about those sneaky maneuvers of the Eisenhower Administration which covertly did more to bring McCarthy down than any of his other enemies were able to accomplish openly. We can, of course, be grateful for a chronology which reminds us of Mr. Eisenhower’s skill at choosing moments when a light push could do the job as effectively as a heavy shove. But we miss any clear explanation of the role of Vice President Nixon, the Blifil whose betrayal did so much to damage this Black George. Mr. Griffith’s references to Nixon leave him murky as always; still there must have been more movement in those shadows at McCarthy’s back than we are vouchsafed here.

There is the occasion in July, 1953, when McCarthy appointed J.B. Matthews as staff director of his Senate subcommittee on investigations. The senator’s enemies discovered that the same month’s American Mercury was displaying an article by J.B. Matthews beginning with the flat assertion that “the largest single group supporting the Communist apparatus is composed of Protestant clergymen.” They saw at once their chance to bring one bigotry into the fight against another; the ensuing scandal produced the first real check to McCarthy and at its end even brought in the White House, where a band of conspirators which seems to have included Vice President Nixon and Deputy Attorney General William Rogers, now his Secretary of State, induced President Eisenhower to issue a statement describing recent attacks upon the clergy as “unjustifiable and deplorable.” Unfortunately Senator McCarthy had already decided to fire Matthews before the President’s statement was ready for issuance.

There then followed a frantic race between McCarthy, who had already decided to let Matthews go, and the White House, which wanted the credit, to see whose release would reach reporters first. The White House won.

That is as far as Griffith’s account goes; and it overlooks that chance for us to understand the subtleties of Mr. Nixon’s treason which is provided by the reminiscences of Emmett John Hughes, a White House assistant and major conspirator.7 Hughes says that he was trying to get Mr. Eisenhower’s signature on the anti-Matthews statement when he got word that McCarthy was on his way to the Senate floor, probably carrying Matthews’s resignation for public announcement and due credit there. Rogers met the crisis by calling the Vice President who hastened from his office, caught McCarthy on his way to the Senate, and held him in conversation until Hughes could give the signal that Mr. Eisenhower’s statement was already in the hands of the press corps.

Mr. Truman had unsuccessfully fought McCarthy as an incubus to sound methods of standing up to Communism. Mr. Nixon had survived McCarthy and even assisted his downfall from the same premise even more fervently held. He helped to destroy McCarthy to save McCarthyism. The insistence that we stood at Armageddon against the Soviets pervaded government after the senator’s overthrow and was even strengthened by the character of the rhetoric which helped so much to accomplish it.

For, in the end, we can agree that McCarthy affronted both Presidents Truman and Eisenhower by the brutal and unfeeling nature of his assault on the proprieties and still have to recognize that he was also distasteful as an inconvenience. However distortedly, he represented a challenge to the executive’s assumption that Congress could not be trusted with anything like disclosure of the operations of our military and diplomatic policies. The alarm of the Eisenhower White House at the threat that McCarthy might investigate the CIA had some of its origin in the fact that, of all senators, he was the least fit for such a task; but it originated just as much in the government’s certainty that the CIA was not a proper subject for the scrutiny even of the best senators, being an institution beyond the competence of the legislature.

For one of the unnoticed and by no means least mischievous consequences of McCarthy’s career was that its course and final wreck established for too long the immunity of the executive from any real legislative challenges to the secrecy with which it has ever since been able to shroud its most fateful decisions. The Senate which saved the White House from McCarthy managed, in the process, to protect the White House, at least for the next decade, from the Senate too.

This Issue

March 11, 1971

-

1

In George III, Lord North and the People (Russell & Russell, 1968). ↩

-

2

The linking in history of Gouzenko and Amerasia is the best example of the period’s habit of confusing categories. The Gouzenko case involved the alliance of attachés of the Soviet embassy in Canada and certain members of that country’s Communist Party in activities that might fairly be described as espionage. In the Amerasia case, three employees of the State Department gave documents to a magazine which then published them. ↩

-

3

In making such distinctions among his citizens, the President was adhering to what had become an established liberal credo. The liberals of this period were quick enough to defend “mistaken identity cases”; but the open Communist Party member could expect no help from them. One or two personal failures of my own may illustrate how pervasive this spirit was. In the Fifties I attempted to persuade a deeply engaged Washington lawyer, revered for his struggle with the inequities of the Congressional committees on behalf of the famous and the innocent, to take as a client a friend of mine who was a Communist Party official and who had been indicted under the Smith Act. The lawyer would not even see us. ↩

-

4

The rumor that J. Edgar Hoover had been marked for extinction by Governor Dewey had originated with Walter Winchell, who was then so devotedly Mr. Hoover’s equerry as to suggest that the FBI director was its source. Mr. Hoover seems, by the way, to have let himself be used as a campaign instrument of the administration in office rather more often than the notions he gives us of his pride might lead us to expect; he seems to scratch the backs of his temporary bosses almost as assiduously as they do his. ↩

-

5

In The Intellectuals and McCarthy (MIT, 1969). ↩

-

6

In I. F. Stone, The Haunted Fifties (Random House, 1963). ↩

-

7

In The Ordeal of Power (Atheneum, 1963). ↩