Lloyd’s most famous bank clerk revalued the poetic currency forty-nine years ago. As Joyce said, The Waste Land ended the idea of poetry for ladies. Whether admired or detested, it became, like Lyrical Ballads in 1798, a traffic signal. Hart Crane’s letters, for instance, testify to his prompt recognition that from that time forward his work must be to outflank Eliot’s poem. Today footnotes do their worst to transform innovations into inevitabilities. After a thousand explanations, The Waste Land is no longer a puzzle poem, except for the puzzle of choosing among the various solutions. To be penetrable is not, however, to be predictable. The sweep and strangeness with which Eliot delineated despair resist temptations to patronize Old Possum as old hat. Particular discontinuities continue to surprise even if the idea of discontinuous form—which Eliot himself was to forsake—is now almost as familiar as its sober counterpart. The compound of regular verse and vers libre still wears some of the effrontery with which in 1922 it flouted both schools. The poem retains the air of a splendid feat.

Eliot himself was inclined to pooh-pooh its grandeur. His chiseled comment, which F. O. Matthiessen quotes, disclaimed any intention of expressing “the disillusionment of a generation,” and said that he did not like the word “generation” or have a plan to endorse anyone’s “illusion of disillusion.” To Theodore Spencer he remarked in humbler mood, “Various critics have done me the honor to interpret the poem in terms of criticism of the contemporary world, have considered it, indeed, as an important bit of social criticism. To me it was only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life. It is just a piece of rhythmical grumbling.”

This statement is prominently displayed by Mrs. Valerie Eliot in her superb decipherment and elucidation of The Waste Land manuscript. If it is more than an expression of her husband’s genuine modesty, it appears to imply that he considered his own poem, as he considered Hamlet, an inadequate projection of its author’s tangled emotions, a Potemkin village rather than a proper objective correlative. Yet no one will wish away the entire civilizations and cities, wars, hordes of people, religions of East and West, and exhibits from many literatures in many languages which lined the Thames in Eliot’s ode to dejection. And even if London was only his state of mind at the time, the picture he paints of it is convincing.

His remark to Spencer, made after a lapse of years, perhaps catches up another regret, that the poem emphasized his disgust at the expense of much else in his nature. It identified him with a sustained severity of tone, with pulpited (though brief) citations of Biblical and Sophoclean anguish, so that he became an Ezekiel or at least a Tiresias. (In the original version John the Divine made a Christian third among the prophets.) While Eliot did not wish to be considered merely a satirist in his earlier verse, he did not welcome either the public assumption that his poetic mantle had become a hair shirt.

In its early version The Waste Land was woven out of more kinds of material and was therefore less grave and less organized. The first two sections had an over-all title (each had its own title as well), “He Do the Police in Different Voices,” a quotation from Our Mutual Friend. Dickens has the widow Higden say of her adopted child, “Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the Police in different voices.” Among the many voices in the first version, Eliot placed at the very beginning a long, conversational passage describing an evening on the town, starting at “Tom’s place” (a rather arch use of his own name), moving on to a brothel, and concluding with a bathetic sunrise:

First we had a couple of feelers down at Tom’s place,

There was old Tom, boiled to the eyes, blind….—(“I turned up an hour later down at Myrtle’s place.

What d’y’ mean, she says, at two o’clock in the morning,

I’m not in business here for guys like you;

We’ve only had a raid last week, I’ve been warned twice….

So I got out to see the sunrise, and walked home.

This vapid prologue Eliot decided, apparently on his own, to expunge, and went straight into the now familiar beginning of the poem.

Other voices were expunged by Eliot’s friend Ezra Pound, who called himself the “sage homme” (male midwife) of the poem. For example, there was an extended, unsuccessful imitation of The Rape of the Lock at the beginning of “The Fire Sermon.” It described the lady Fresca (imported to the waste land from “Gerontion” and one day to be exported to the States for the soft drink trade). Instead of making her toilet like Pope’s Belinda, Fresca is going to it, like Joyce’s Bloom. Pound warned Eliot that since Pope had done the couplets better, and Joyce the defecation, there was no point in another round. To this shrewd advice we are indebted for the disappearance of such lines as:

Advertisement

The white-armed Fresca blinks, and yawns, and gapes,

Aroused from dreams of love and pleasant rapes.

Electric summons of the busy bell

Brings brisk Amanda to destroy the spell…Leaving the bubbling beverage to cool,

Fresca slips softly to the needful stool,

Where the pathetic tale of Rich- ardson

Eases her labour till the deed is done…

This ended, to the steaming bath she moves,

Her tresses fanned by little flut- t’ring Loves;

Odours, confected by the cunning French,

Disguise the good old hearty fe- male stench.

The episode of the typist was originally much longer and more laborious:

A bright kimono wraps her as she sprawls

In nerveless torpor on the window seat;

A touch of art is given by the false

Japanese print, purchased in Ox- ford Street.

Pound found the decor difficult to believe: “Not in that lodging house?” The stanza was removed. When he read the later stanza,

—Bestows one final patronising kiss,

And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit;

And at the corner where the stable is,

Delays only to urinate, and spit,

he warned that the last two lines were “probably over the mark,” and Eliot acquiesced by canceling them.

Pound persuaded Eliot also to omit a number of poems which were for a time intended to be placed between the poem’s sections, then at the end of it. One was a renewed thrust at poor Bleistein, drowned now but still haplessly Jewish and luxurious under water:

Full fathom five your Bleistein lies

Under the flatfish and the squids.Graves’ Disease in a dead jew’s/ man’s eyes!

Where the crabs have eat the lids….That is lace that was his nose….

Roll him gently side to side

See the lips unfold unfold

From the teeth gold in gold….

Pound urged that this and several other mortuary poems did not add anything either to The Waste Land or to Eliot’s previous work. He had already written “the longest poem in the English langwidge. Don’t try to bust all records by prolonging it three pages further.” As a result of this resmithying by il miglior fabbro, the poem gained immensely in concentration. Yet Eliot, feeling too solemnized by it, thought of prefixing some humorous doggerel by Pound about its composition. Later, in a more resolute effort to escape the limits set by The Waste Land, he wrote “Fragment of Agon,” and eventually, “somewhere the other side of despair,” turned to drama.

Eliot’s remark to Spencer calls The Waste Land a personal poem. His critical theory was that the artist should seek impersonality, but this was probably intended as not so much a nostrum as an antidote, a means to direct emotion rather than let it spill. His letters indicate that he regarded his poems as consequent upon his experiences. When a woman in Dublin remarked that Yeats had never really felt anything, Eliot asked in consternation, “How can you say that?” The Waste Land compiled many of the nightmarish feelings he had suffered during the seven years from 1914 to 1921, that is, from his coming to England until his temporary collapse.

Thanks to the letters quoted in Mrs. Valerie Eliot’s Introduction, and to various biographical leaks,* the incidents of these years begin to take shape. In 1914 Eliot, then on a traveling fellowship from Harvard, went to study for the summer at Marburg. The outbreak of war forced him to Oxford. There he worked at his doctoral dissertation on F.H. Bradley’s Appearance and Reality. The year 1914-15 proved to be pivotal. He came to three interrelated decisions. The first was to give up the appearance of the philosopher for the reality of the poet, the second was to marry, and the third to settle in England.

He obtained much encouragement in all three from Ezra Pound, whom he met in September, 1914. Pound read the poems which no one had been willing to publish and pronounced his verdict, that Eliot “has actually trained himself and modernized himself on his own.” Harriet Monroe, the editor of Poetry, must publish them, beginning with “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It took Pound some time to bring her to the same view, and it was not until June, 1915, that Eliot’s first publication took place. This was also the month of his first marriage, on June 26. His wife was Vivienne Haigh-Wood, and Eliot remained, like Merlin with another Vivian, under her spell, beset and possessed by her intricacies for fifteen years and more.

Advertisement

What the newlyweds were like is recorded by Bertrand Russell, whom Eliot had known at Harvard. In a letter of July, 1915, Russell wrote of dining with them:

I expected her to be terrible, from his mysteriousness; but she was not so bad. She is light, a little vulgar, adventurous, full of life—an artist I think he said, but I should have thought her an actress. He is exquisite and listless; she says she married him to stimulate him, but finds she can’t do it. Obviously he married in order to be stimulated. I think she will soon be tired of him. He is ashamed of his marriage, and very grateful if one is kind to her.

Eliot’s parents did not take well to their son’s doings, though they did not, as has been said by Sencourt, cut him off. His father, president of the Hydraulic Press Brick Company of St. Louis, had expected his son to remain a philosopher, and his mother, though a poet herself, did not like the vers libre of “Prufrock” any better than the free and easy marriage. To both parents it seemed that bright hopes were being put aside for a vague profession in the company of a vague woman in a country only too distinctly at war. They asked to see the young couple, but Vivienne Eliot was frightened by the perils of the crossing, perhaps also by those of the arrival. So Eliot, already feeling “a broken Coriolanus,” as Prufrock felt a Hamlet manqué, took ship alone in August for the momentous interview.

His parents urged him to return with his wife to a university career in the States. He refused, he would be a poet, and England provided a better atmosphere in which to write. They urged him not to give up his dissertation when it was so near completion, and to this he consented. He parted on good enough terms to request their financial help when he got back to London, and they sent money to him handsomely, as he acknowledged. Not handsomely enough, however, to release him from the necessity of very hard work. He taught for a term at the High Wycombe Grammar School, between Oxford and London, and then for two terms at Highgate Junior School. He completed his dissertation and was booked to sail on April 1, 1916, to take his oral examination at Harvard; when the crossing was canceled his academic gestures came to an end. In March, 1917, he took the job with Lloyd’s Bank at which he stuck for eight years.

During the early months of their marriage the Eliots were helped also by Russell, who gave them a room in his flat, an act of benevolence not without complications for all parties. Russell found the couple devoted to each other, but noted in Mrs. Eliot a sporadic impulse to be cruel toward her husband, not with simple but with Dostoevskyan cruelty. “I am every day getting things more right between them,” Russell boasted, “but I can’t let them alone at present, and of course I myself get very much interested.” The Dostoevskyan aspect affected his imagery: “She is a person who lives on a knife-edge, and will end as a criminal or a saint—I don’t know which yet. She has a perfect capacity for both.”

The personal life out of which came Eliot’s personal poem now began to be lived in earnest. Vivienne Eliot suffered obscurely from nerves, her health was subject to frequent collapses, she complained of neuralgia, of insomnia. Ezra Pound, who knew her well, was worried that the passage in The Waste Land,

“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

Speak to me. Why do you never speak? Speak.

What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

might be too photographic. But Vivienne Eliot, who offered her own comments on her husband’s verse (and volunteered two excellent lines for the lowlife dialogue in “A Game of Chess”), marked the same passage as “Wonderful.” She relished the presentation of her symptoms in broken meter. She was less keen, however, on another line from this section,

The ivory men make company between us,

and got her husband to remove it. Presumably its implications were too close to the quick of their marital difficulties. Years afterward Eliot made a fair copy of The Waste Land in his own handwriting, and reinserted the line from memory. (It should now be added to the final text.) But he had implied his feelings six months after his marriage when he wrote in a letter to Conrad Aiken, “I have lived through material for a score of long poems in the last six months.”

Russell commented less sympathetically about the Eliots later, “I was fond of them both, and endeavoured to help them in their troubles until I discovered that their troubles were what they enjoyed.” Eliot was capable of estimating the situation shrewdly himself. In his poem “The Death of Saint Narcissus,” which Poetry was to publish in 1917 and then, probably at his request, failed to do, he wrote of his introspective saint, “his flesh was in love with the burning arrows…. As he embraced them his white skin surrendered itself to the redness of blood, and satisfied him.”

For Eliot, however, the search for suffering was not contemptible. He was remorseful about his own real or imagined feelings, he was self-sacrificing about hers, he thought that remorse and sacrifice, not to mention affection, had value. In the Grail legends which underlie The Waste Land, the Fisher King suffers a Dolorous Stroke which maims him sexually. In Eliot’s case the Dolorous Stroke had been marriage. He was helped thereby to the poem’s initial clash of images, “April is the cruellest month,” as well as to hollow echoes of Spenser’s Prothalamion (“Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song”). From the barren winter of his academic labors Eliot had been roused to the barren springtime of his nerve-wracked marriage. His life spread into paradox.

Other events of these years seem reflected in the poem. The war, though scarcely mentioned, exerts pressure. In places the poem may be a covert memorial to Henry Ware Eliot, the unforgiving father of the ill-adventured son. Henry Eliot died in January, 1919, and Eliot’s first explicit statement of his intention to write a long poem comes in letters written later in the year. The references to a father’s death probably derive as much from this actual death as from The Tempest, to which Eliot’s notes evasively refer. As for the drowning of the young sailor, whether he is Ferdinand or a Phoenician, the war furnished Eliot with many examples, such as Jean Verdenal, a friend from his Sorbonne days, who was killed in the Dardanelles. But it may be as well an extrapolation of Eliot’s feeling that he was now fatherless as well as rudderless.

The fact that the principal speaker appears in a new guise in the last section, with its imagery of possible resurrection, suggests that the drowning is to be taken symbolically rather than literally, as the end of youth. Eliot was addicted to the portrayal of characters who had missed their chances, become old before they had really been young. So the drowned sailor, like the buried corpse, may be construed as the young Eliot, buried in or about “l’an trentièsme de son eage,” like the young Pound in the first part of Hugh Selwyn Mauberley.

It has been thought that Eliot wrote The Waste Land in Switzerland while recovering from a breakdown. But much of it was written earlier, some in 1914 and some, if Conrad Aiken is to be believed, even before. A letter to Quinn indicates that much of it was on paper in May, 1921. The breakdown or, rather, the rest cure did give Eliot enough time to fit the pieces together and add what was necessary. At the beginning of May, 1921, he consulted a prominent neurologist, who advised three months away from remembering “the profit and loss” of Lloyd’s Bank. When the bank had agreed, Eliot went first to Margate and stayed for a month from October 11. There he reported to Richard Aldington that his “nerves” came not from overwork but from an “aboulie” (Hamlet’s and Prufrock’s disease) and “emotional derangement which has been a lifelong affliction.”

But whatever reassurance this diagnosis afforded, he resolved to consult Dr. Roger Vittoz, a psychiatrist in Lausanne. He rejoined Vivienne and on November 18 went with her to Paris. It seems fairly certain that he discussed the poem at that time with Ezra Pound. In Lausanne, where he went by himself, Eliot worked on it and sent revisions to Pound and to Vivienne. Some of the letters exchanged between him and Pound survive. By early January, 1922, he was back in London, making final corrections. The poem was published in October.

The manuscript had its own history. In gratitude to John Quinn, the New York lawyer and patron of the arts, Eliot presented it to him. Quinn died in 1924, and most of his possessions were sold at auction; some, however, including the manuscript, were inherited by his sister. When the sister died, her daughter put many of Quinn’s papers in storage. But in the early 1950s she searched among them and found the manuscript, which she then sold to the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library. The then curator enjoyed exercising seignorial rights over the collection, and kept secret the whereabouts of the manuscript. After his death its existence was divulged, and Valerie Eliot was persuaded to do this knowledgeable edition.

She did so the more readily, perhaps, because her husband had always hoped that the manuscript would turn up as evidence of Pound’s critical genius. It is a classic document. No one will deny that it is weaker throughout than the final version. Pound comes off very well indeed; his importance is comparable to that of Louis Bouilhet in the history of the composition of Madame Bovary. Yeats, who also sought and received Pound’s help, described it to Lady Gregory, “To talk over a poem with him is like getting you to put a sentence into dialect. All becomes clear and natural.” Pound could not be intimidated by pomposity, even Baudelairean pomposity:

London, the swarming life you kill and breed,

Huddled between the concrete and the sky;

Responsive to the momentary need,

Vibrates unconscious to its formal destiny.

Next to this he wrote “B-ll-S.” (His comments appear in red ink on the printed transcription which is furnished along with photographs of the manuscript.) Pound was equally peremptory about a passage which Eliot seems to have cherished, perhaps because of childhood experiences in sailing. It was the depiction at the beginning of “Death by Water” of a long voyage, a modernizing and Americanizing of Ulysses’ final voyage as given by Dante:

Kingfisher weather, with a light fair breeze,

Full canvas, and the eight sails drawing well.

We beat around the cape and laid our course

From the Dry Salvages to the eastern banks.

A porpoise snored upon the phosphorescent swell,

A triton rang the final warning bell

Astern, and the sea rolled, asleep.

From these lines Pound was willing to spare only

with a light fair breeze

We beat around the cape from the Dry Salvages.

A porpoise snored on the swell.

All the rest was—seamanship and literature. It became clear that the whole passage might as well go, and Eliot asked humbly if he should delete Phlebas as well. But Pound was as eager to preserve the good as to expunge the bad: he insisted that Phlebas stay because of the earlier references to the drowned Phoenician sailor. With equal taste, he made almost no change in the last section of the poem, which Eliot always considered to be the best, perhaps because it led into his subsequent verse.

Eliot did not bow to all his friend’s revisions. Pound feared the references to London might sound like Blake, and objected specifically to the lines,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the time,

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

Eliot wisely retained them, only changing “time” to “hours.” Next to the passage,

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

They called me the hyacinth girl,”

Pound marked “Marianne,” and evidently feared—though Mrs. Eliot’s note indicates that he has forgotten—that the use of quotation marks would seem an imitation of Marianne Moore. But Eliot, for whom the moment in the hyacinth garden had obsessional force—it was based in part on an incident in his own life—made no change.

Essentially Pound could do for Eliot what Eliot could not do for himself. There was some reciprocity, because when the first three Cantos appeared in 1917, Eliot offered criticism which resulted in their being completely altered. It seems, from the revised versions, that he objected to the elaborate windup, and urged a more direct confrontation of the reader and the material. A similar theory is at work in Pound’s changes in The Waste Land. Chiefly by excision, he enabled Eliot to tighten his form. Perhaps partially in reaction, he studied out means of loosening his own in the Cantos.

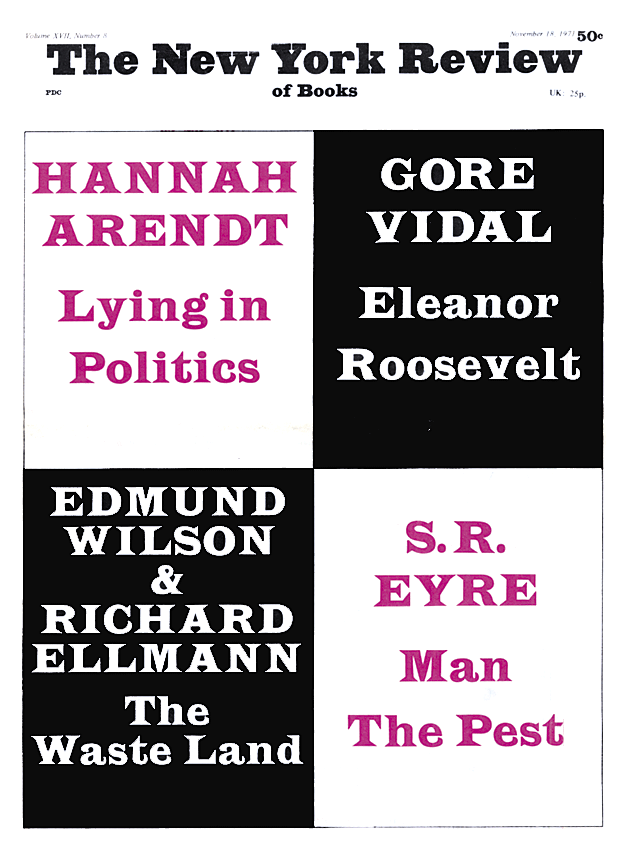

This Issue

November 18, 1971

-

*

Among them is the new book by the late Robert Sencourt, T.S. Eliot: A Memoir, edited by Donald Adamson (Dodd, Mead, 1971), which is the first biography: Sencourt is undependable in fact and in interpretation. The animating theme, though whispered only in the book’s corners, is that Eliot was homosexual. This and other distortions are self-discrediting. The book has, however, some excellent photographs. ↩