IN A LARGE GREEK COLONY, 200 B.C.

That things in the Colony aren’t what they should be

no one can doubt any longer,

and though in spite of everything we do move forward,

maybe—as more than a few believe—the time has come

to bring in a Political Reformer.

But here’s the problem, the objection:

they make a tremendous fuss

about everything, these reformers.

(What a relief it would be

if they were never needed.) They probe everywhere,

question the smallest detail,

and right away think up radical reforms

that demand immediate execution.

Also, they have a liking for sacrifice:

GET RID OF THAT POSSESSION;

YOUR OWNING IT IS PRECARIOUS:

POSSESSIONS LIKE THOSE ARE WHAT RUIN COLONIES.

GET RID OF THAT INCOME,

AND THE OTHER CONNECTED WITH IT,

AND THIS THIRD, AS A NATURAL CONSEQUENCE:

THEY ARE SUBSTANTIAL, BUT WHAT CAN ONE DO?

THE RESPONSIBILITY THEY CREATE IS DAMAGING.

And as they extend the range of their control

they find an endless number of useless things to eliminate—

things which are, however, difficult to give up.

And when, all being well, they finish the job,

every detail now diagnosed and sliced away,

and they retire (also taking the wages due to them),

it’s a wonder anything’s left at all

after such surgical efficiency.

Maybe the moment hasn’t arrived yet.

Let’s not be too hasty: speed is a dangerous thing.

Untimely measures bring repentance.

Certainly, and unhappily, many things are wrong in the Colony.

But is there anything human without some fault?

And after all, you see, we do move forward.

A PRINCE FROM WESTERN LIBYA

Aristomenis, son of Menelaos,

the Prince from Western Libya,

was generally liked in Alexandria

during the ten days he spent there.

In keeping with his name, his dress was also modestly Greek.

He received honors gladly,

but he didn’t solicit them; he was unassuming.

He bought Greek books,

especially history and philosophy.

Above all he spoke very little.

Word spread that he must be a profound thinker,

and men like that naturally don’t speak very much.

He was neither a profound thinker nor anything at all—

just a piddling, laughable man.

He assumed a Greek name, dressed like the Greeks,

learned to behave more or less like a Greek;

and all the time he was terrified he’d spoil

his reasonably good image

by coming out with barbaric howlers in Greek

and the Alexandrians would start making fun of him,

as they have a way of doing, those disgusting people.

This was why he limited himself to a few words,

terribly careful of his syntax and pronunciation;

and he suffered no little agony, having

conversation on conversation heaped up inside him.

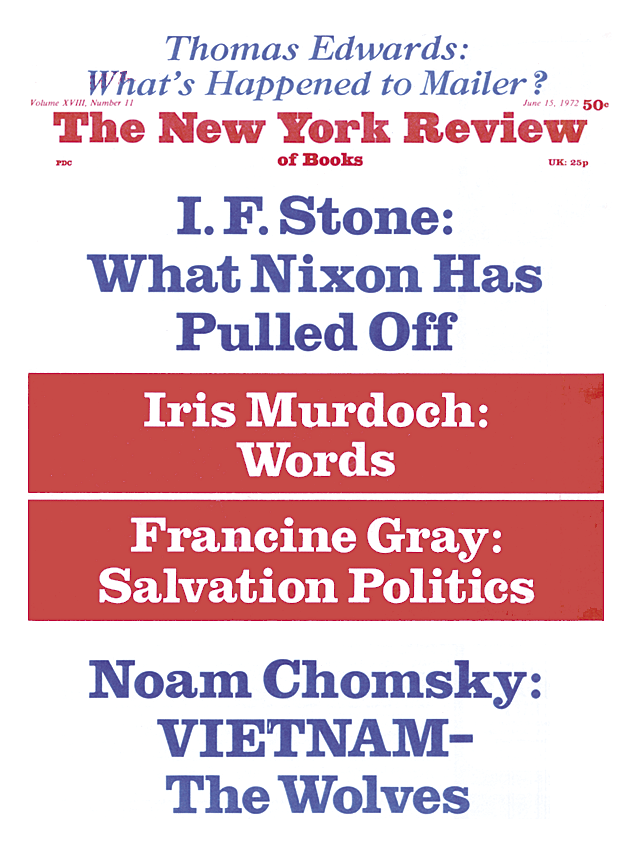

This Issue

June 15, 1972