Uncommon is the word for Chester Kallman—uncommonly attractive and uncommonly odd. Probably no other poet of Chester Kallman’s generation, the generation of “the nineteen-twenties-born,” the generation which, as he mordantly remarks, “had no name,” seems so singular, so dryly or vividly himself. And yet, for all that, no other poet, I think, seems, here and there, so quaint, so much the poor proverbial drunk endlessly searching for his wallet under the streetlamp although he lost it up the alley. Storm at Castelfranco and Absent & Present and The Sense of Occasion—certainly the three collections of his poems are arresting performances. And certainly a number of the poems grow better from book to book, poems full of nipping lines, of “wry and borrowed ambiguities,” of contraries and conceits.

Yet often with Kallman just when a fancy’s having its head it becomes gnarled, just when the whimsey sparkles or stirs it turns crabbed. Here is a poet who knows most of what there is to know about meter and form (the mesmeric iambs of “Missing the Sea,” the exquisite syllabic variants of “The African Ambassador”). And here is a poet who knows most of what there is to know about rhetoric (the bravura style of “Testament of the Royal Nirvana”—it is small-scale virtuosity, but virtuosity nonetheless). Yet here, alas, is a poet who, now and again, appears to know nothing—or to know everything and forget everything—about tone.

Tone, after all, is the heart of the poem, “the heart hot within,” as the Psalmist says. It is what makes or breaks a voice. I don’t, of course, mean tone color. The author of “Griselda Sings” or “Weighty Questions” is a master of consonants and vowels; these poems, in particular, have the grace and delicacy of a Vittoria madrigal. I mean, rather, the steady dramatic shaping of one’s moods, one’s expectancy, one’s belief. About that, I think, Chester Kallman can be astonishingly inapt.

Consider “The Body’s Complaint to the Soul,” for instance. It is a pretty, playfully allegorical quarrel between the fleshly and the idyllic, the “cage” of appetite and the “lark” of spirit. The couplets are a bit sprung, but the poem, in its rippling way, is stately enough, and the reader ripples along pleasantly with it. But then, lo and behold, a bolt from the blue:

As I live,

Miss Skylark! titivated in

The touchy dungeon of my skin….

What is one to make of that? Is it John Rechy misreading Ronald Firbank, or Firbank mimicking John Rechy? And all the other inconsistencies of tactic and tone in all the other poems, which, in so exacting, so moving or witty a poet, cannot help but rankle the reader. All those hot-house jokes (“Come as you are if you have nothing on“), all those fey interjections (“My foot!”), all the lexicographer specialties or Anglo-American slang (“Orts of me,” “beastly,” “con”), all the greenroom improvisations on the theme of “We Happy Few,” worthy, no doubt, of Bunthorne and Grosvenor and the battle of the aesthetes in Patience.

Coleridge tells us that “a continuous undercurrent of feeling everywhere present” is what we most often look for in a work of art, but that the feeling is “seldom anywhere a separate excitement.” Chester Kallman, it seems to me, has a good deal of dissiliency, a starting asunder or a springing apart, a sort of fluttery distinctiveness which can indeed be a “separate excitement”; but he has, except in those poems where he’s most possessed by his subject, little of resiliency, that striking power or capability of a “strained body to recover,” as Webster’s says, “its size and shape after deformation.”

In the three collections of his poems, he looks back, I think, to the age of Dryden and Etherege and Pope, to the shimmering stanza and the ceremonious quip; and then looks ahead to modernist or expressionist practice, to the jagged and the idiomatic: the dark side of Graves, the light side of Auden, the Theodore Roethke of The Lost Son or Praise to the End, and Marianne Moore. It is the meeting between these highly idiosyncratic styles, or the lack of it, that accounts, I suppose, for the medley of masks and moods, the great charm and eccentricity of his work.

He is a didactic poet, a romantic poet, and a comic poet. As the latter he has the comic poet’s view of the world, the cosmopolitan buzz of the “Bores and Bored,” of “gossipers” and “gossipees.” With Kallman, the world is usually a musico-literary set in Athens or Austria or New York, a world where the way and the truth are paradoxical (“Austere, factual, theater to the core”), where we have punsters or parodists but never buffoons, or party birds and bar flies (the delightful “An Encounter”), or erubescent figures of fun who grow a little pale over—well, over a baby:

Advertisement

I must leave home or go crazy.

Those Hystereo-radios!

And that baby:

His cooing parents, our neighbors,

Must have given him a microphone for his birthday.

“Urban History” and “Look on the Ant” are cautionary poems, poems whose moral and formal properties illustrate a lesson:

And men who emulate with love

The ant are soon the victims of Impossible ideals

The jollifications of “Nightmare of a Crook” illustrate a lesson, too: Don’t be greedy! Always sensual and appetitive, Kallman has, predictably, a fondness for food, even, shamelessly, “food for thought.” He must surely be one of the few poets writing who can make of sauces and spices, the killing of the Great White Goose, of fingers and lips, liver and belly the savory parts of an aphoristic commentary.

His real glory, however—where he’s most himself, or at least most securely himself—is, I feel, when he becomes more or less obsessed with more or less operatic themes, romantic infidelity and romantic fidelity: Il est beau de mourir en s’aimant—the most operatic theme of all. It is here that his lively or luxuriant imagination, with its natural inclination toward the indiscreet, departs from the classical restraint or the coterie preciosity which can—sorely, at times—so blinker his style. The terrifically hard-bitten “The Middle of the Night: The Hands,” fierce in its particulars, pitiless in feeling, has a rhythmically brilliant, almost staccato lilt, its lines and images full of an abrupt intensity and a pressing refrain:

I pity those who fall into your hands…

God help us both if we are in his hands

Reading the poem, certainly one of the best end-of-the-affair poems of the day, you pass beyond the merely epigrammatic or the merely anecdotal and, as they say, touch the man. Through it, and other poems (“Like As Not,” “Griselda Sings,” the febrile heraldic landscape of “Delphi”), the reader has an exhilarating sense of calamity always around the corner, the fear that one is not being loved enough or that one is not being taken seriously enough, the fear that one cannot really be loved or that one cannot really be serious, the preponderant infatuation with those older than oneself or those younger. Romantic poetry—in our addled age, at least—is essentially self-portraiture; it lives or dies, really, according to how inclusively honest a poet can be. Mocking toward others (the “self-possessed affairs” of his friends), Kallman is equally mocking toward himself: a little frivolous in vice, more than a little unbelieving in passion (“Intense but narrow, my dear,” as he has a friend remark, probably truthfully, of himself).

The tour de force of his latest collection, The Sense of Occasion, the extraordinary sequence of poems called “The African Ambassador,” is, I believe, romantic, too—though with a good deal more gravity, more range; its theme less the difficulties of a statesman than the difficulties of la condition humaine, the difficulty of being human at all. The telling epigraph is from Graham Greene: “To me…Africa will always be the Africa of the Victorian atlas, the blank unexplored continent the shape of the human heart.”

What Kallman has done, what Berryman and Yeats have also done in altogether different works, is to create a public persona for his private demons, a wickedly imagined and mysteriously ironic figure of state: the punctilious representative of the Moor and the Bantu, “strolling hatless through Rome”; the “exile” contemplating minaret and campanile and embassy gardens; the suave but embittered ambassador at Naples looking at a “Lone date palm black upon/The backdrop of the blue bay,/Fruitless” where “Africa begins”; the ambassador, on one of his “night voyages,” amorously fingering “Where the heart’s black heart lies wrapped: South. Sud. Sudare. Sweat”; the ambassador, more European than African, who thinks “human/Means cosmopolitan”; the ambassador, fattened by memory, starved by the present, who knows that in “A full-length looking glass,” “You meet yourself and pass.”

These poems (and the best of them seem to be “His Private Collection,” “His Tour of Naples,” “His Night Voyages,” “His Upper Class Love Affair,” “His Reasons for Locking Doors”) are so genuinely intercadenced and interrelated, so full of the black arts of diplomacy, of “journeyings,” of the intricacies of music and language themselves, that they are not, alas, amenable to quotation. Still, perhaps, two stanzas, the second and the third from “His Upper Class Love Affair,” can suggest how flashingly direct and indirect Chester Kallman can be—and how sad it is, finally, that we do not have such tart or impassioned excellence more often:

What do you hear? The cry

Of pinned worms from that neb.

What do you see? A fly

In that abandoned web.

Feel? Oh hold me! We held

Hours, years, held teeth and nails

Rounding to one hard-shelled

Universe like two snails.

What’s love? An open door:

New names and natures line

The revealed corridor

Down to its last confine

A full-length looking glass.

You meet yourself and pass.What’s love? Look at the sky.

The gate’s locked! Very well.

Teach me your magic! I?

You, only you! Oh hell,

There’s nothing one can tell.

If I can’t know, I’ll die!

Die. Of shame! You? You smell

Of last night’s drinks gone dry.

Back for the morning meal,

With all the rest I serve

Myself and dread they feel

That I feel through each hair

A vine-tip made, a nerve,

Love dead, love everywhere.

Most of the poems of William Meredith are so balanced and modest and appealing, composed in so many uncomplicated and civilized ways, so much the sort of poetry appropriate to read on a lazy afternoon, perhaps even to read while listening to Dietrich sing “Lazy Afternoon,” that an intemperate spirit might, at times, wonder—no doubt, frivolously—what would happen if Professor Meredith read nothing but Rimbaud or Mayakovsky or—heaven help us—Anais Nin? Would the climate in Connecticut change, would there be unruly declamations, moments of fine excess, would one go absolutely out of one’s squash? It seems unlikely. William Meredith, a durable, though admittedly minor, poet, has always had a conservative sense of people and place. He offers two mottoes—“The Poet as Troublemaker” and “Iambic Feet Considered as Honorable Scars”—and only the most thoughtless of his readers would ever be hard put to know which of these mottoes was closest to the professor’s heart.

Advertisement

In the New and Selected Poems we follow him moving gracefully over the years from the authority of the military life (the Second World War, “the bomb’s luck, the gun’s poise and chattering”) to the authority of the university (for a while it seemed as if Professor Meredith would become the academic poet par excellence) to that, finally, of the suburban and reflective style of his most recent and most successful stage.

If he is really too disciplined and adjusted an individual, too genial, too much the hero of the buried life, harumping among the hydrangea bushes, he is, nevertheless, a poet who knows, deep to his fingertips, what the tiger or the nightingale always forgets, that the dispassionate, domestic, monogamous world has its dramas and sorrows, that rectitude itself can be an adventure, a moral adventure almost as Kierkegaard dreamed, that if “identity is a travelling-piece for some,” for the poet, for this poet, “here is what calls me, here what I call home.” That, within it, “there is no end to the/Deception of quiet things/And of quiet, every-day/People a lifetime brings”; that the common routine, in its diffident way, is a magical contrivance; that the common experience can be a fable, and “yet all of a piece and clever/And at some level, true.”

Very likely Professor Meredith would agree with Plato that “to prefer evil to good is not in human nature”—or agree and not agree. For it is that assenting and dissenting, the gentle skepticism, that charmingly understated, and often unexpected, weighing of philosophical alternatives which can, I think, so enhance his work. That, and another quality, closer to prose, a quality which seems, in its naturalistic details, its air of reasonableness and muted Freudianism, reminiscent of the tales of William Maxwell, the beautiful furtive simplicity of The Folded Leaf, the fellowship of Limey and Spud, the troubled undergraduates who, no matter how subtly or how darkly they stray, always return, in acceptance and gladness, to the middle road, the middle way.

The roots to a New England past, to a truth-saying, faintly elegiac past, are there in Meredith, as they are there in Maxwell, and in an age hell-bent on destroying every amenity, every grace, an age certain of nothing except the tintinnabulation of the next havoc, the next craze, they must haunt the poet as perhaps only a last inheritor who knows he is a last inheritor can be haunted.

So the quotidian moments, burdensome, unadorned; so, too, the night side of life always re-creating itself under the light of common day—these prompt the poems, the newer poems, especially: level-headed songs (lieder, if not arias) about nature and memory, parents and dying, about “an old field mowed for appearances’ sake,” about an elderly neighbor chatting vaguely of Shelley, about a mugging on a stairway and a “brown face briefly/phrased like a question.” At times these rise—or almost rise—to eloquence (the marvelous conclusion of “The Wreck of the Thresher”), but more often settle for a comeliness and a rightness (“The Open Sea,” “The Chinese Banyan”), or an emblematic morality (“Fables about Error”), which Professor Meredith, in the best of his poems, achieves so discreetly, so steadily, so well.

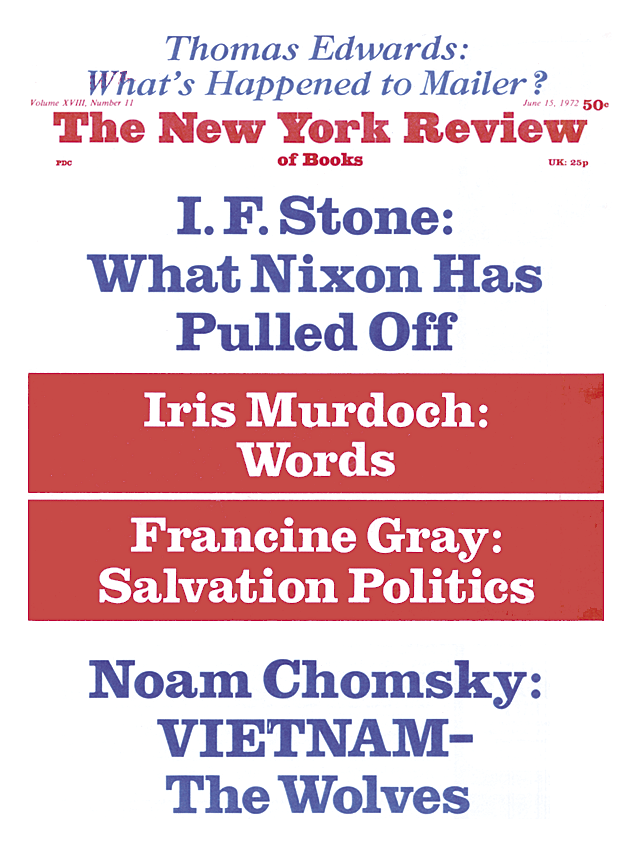

This Issue

June 15, 1972