Once, long ago, there were only novelists, content to make up stories they hoped might amuse, excite, or improve the character. Now, however, we also have “serious novelists,” writers who keep worrying themselves and their readers about art and ideas, determined to be significant even if it kills us. A serious novel doesn’t achieve seriousness, the real thing, simply by warning you not to relax and enjoy; and it risks something in its insistence on seeming more than the commercial product.

Here are four serious novels by intelligent and practiced writers, with some nineteen books to their collective credit. Each has his own sense of experience and his own scrupulosities about his art. But as it gets harder and harder to write a really bad novel—compare Love Story or even Airport with the really bad novels of fifty years ago—it also seems to get harder to write a really good one. I wish I liked the worst of these books less, and the best better. But the center holds all too well, since the center is the tactical sophistication all novelists, serious or otherwise, now carry in their pockets. Even out at the crazy edges, where imagination struggles to reconcile form with life, things now feel pretty stable; imaginative struggles have become the most conventional of fictional conventions.

But of course one must discriminate. Certainly Jose Yglesias isn’t a very edgy novelist. In The Truth About Them the obligatory skepticisms stir around in a narrator who is reconstructing a family history that began before he was there to record it. Occasionally he says that his knowledge is incomplete, his understanding tentative, and so on; it is thus that one maintains membership in a tricky craft. But mostly The Truth About Them, though told episodically and with a lot of temporal crisscross, means what the title says.

Yglesias’s seriousness is decently old-fashioned. The novel concerns the lives of a Cuban-American family in Florida and Depression New York, from the mid-nineteenth century to now. Pini, the narrator, is of its nearly assimilated third generation. Now middle-aged, a veteran of World War II, and a journalist turned novelist, he lives in New York with his Jewish wife and two up-to-date children, one of whom, a student radical blooded at Columbia, goes underground as the book ends. Pini’s grandmother, the long-dead matriarch whose remembrance hovers over the lives of her children and grandchildren, was an aristocratic girl from Matanzas who left Cuba to bear an illegitimate child whose father she was too proud to marry. She met and married an émigré cigar maker, and settled into a working-class life she mastered without ever quite accepting. Her reach for freedom, with its ambiguous results, is the thread Pini pursues through the family’s experience.

Yglesias’s perspective on America has considerable freshness. These are not the conventional poor people of social protest novels, though they knew poverty well enough in hard times and felt the confused and inept discriminations of Crackers who weren’t quite sure whether Latins were Niggers. As Cubans the family had an identity that for a time remained indifferent to the pressures of their new land. Success, not suffering, dissolves this identity as the third generation begins to prosper, as third generations somehow tend to do.

It is here that Yglesias’s sense of his subject, poised and loving when focused on prelapsarian days, falters in a way that Pini’s occasional uncertainties can’t justify. The story of his sister Eloisa, for example, much too neatly epitomizes assimilation—she marries in turn a communist cigar maker who adores her but can’t resist other girls either, an intellectual Jewish union organizer, and a prosperous Anglo lawyer named Wilfred Pettigrew (her sexual life, needless to say, is all downhill), surviving them all to live in Tampa’s most exclusive suburb next door to a kindly and helpful mafioso. Life indeed plays strange tricks, but art does better to pass them up.

Finally Yglesias isn’t sure how to play it. As figures in a political landscape the family has possibilities. The strongly felt, independent, and rather aimless radicalism of Hispanic working people is nicely rendered; and their enthusiasm for Castro and contempt for the bourgeois refugees who fled him to infest Florida provide a counterpoint to the family’s emergence into the comforts of middle-class America, as does their cautious approval for Pini’s radical son. (He has yet to learn what they know, that survival, however passive and silent, is also a mode of freedom.)

But this material is jostled by a kind of ethnic comedy that, for all of Pini’s embarrassment, sounds a little like tomming for the Anglo reader, as in the stories of Pini’s aunt “Mama Chucha” (who, almost by accident, had fifteen children and fell out of the car en route to her mother-in-law’s deathbed) and her husband “Papa Leandro” (who was fat and guilefully clownish but a marvelous dancer and became a minor poet in old age). Yglesias may want us to ascribe the cuteness to Pini’s difficulties about his own mixed identity, but I’m afraid it may recommend The Truth About Them to less judicious readers than the book otherwise has its eye on.

Advertisement

Hubert Selby’s The Room is very obscene, in inventive as well as boring ways, and it too will attract readers who really shouldn’t be there. Here point of view is all, as Selby ransacks the paranoid mind of a prisoner waiting to be tried, apparently on a minor charge. I say “apparently” because this is one of those novels that accord merely “objective” details very little status. The prisoner fantasizes endlessly, and I can’t tell whether the bit of court transcript near the end, where he seems to be charged with loitering with intent outside a jewelry store window, should be taken as fact or as a depressive replay of earlier fantasies of triumph and vindication.

But it doesn’t matter. The prisoner is guilty of something, everything—his pitiful psychopath’s brain contains the intention of all possible crimes, along with the conviction of perfect innocence. And Selby, who in Last Exit to Brooklyn so impressively showed his power to imagine psychosexual extremity and the lurid despairs inside seemingly commonplace souls, gives this prisoner plenty to think about, as he dreams up hideous vengeances on cops, women, and the other authority figures of his humiliating history.

But it’s terribly difficult to render, from inside, dull and resourceless minds like this one. The trick is not to suggest that such people really are richly aware and sensitive when you get to know them, down there beneath the impassive, inarticulate surface. Few writers even come close—offhand I think only of Defoe, Flaubert, and Joyce, which is select company. Selby is a conscientious craftsman—the raw immediacy of Last Exit was sustained by a remarkable sense of structure and timing. But, like everyone else, he’s no Joyce, and The Room falls short of its ambitions.

The prisoner remembers a lower-middle-class childhood in the Thirties, when model planes were frustrating to make but fun to set fire to afterward, when the spirits of Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd presided over games of Cops and Robbers, when (a few years later) it cost only a quarter to get into the Saturday matinee for double-feature feel-ups with your girl. More generally he recalls bewilderment and pent-up violence, inadequacies at school, anxiety about being a mama’s boy, fear of policemen and adults in general, without sustaining comradery with other children.

But this familiar matter doesn’t add up to the poor monster Selby shows us—as Kenneth Burke once replied to simplistic theories of psychic formation, “Many are weaned but few are Kierkegaards.” Selby attacks our smug assumption of distance from the psychopathic—to the extent that we share the prisoner’s memories we are implicated in his sickness—but something is missing. He remembers nothing after early puberty; one can’t tell, for example, how his early sex life, strangely ignorant of the very idea of coitus, connects with his adult fantasies of copious intercourse, conventional and (especially) anal. Something must have happened in between, something we luckily were spared, and without these middle terms the prisoner’s case seems too diagrammatic and classic to be scary and moving enough.

Inconsistency is a narrative problem here. One has trouble identifying a mind that remembers being ridiculed for calling the denominator of a fraction the “plural” yet even now defends the answer because the number was larger than one, a mind whose usual idiom is an obsessive and witless obscenity (“Jesus, this fucking world stinks. People are nothing but a bunch of shits”), with the mind that finds a decent eloquence for self-pity:

That terrible, overwhelming feeling of loneliness that makes you unaware of crowded streets and noisy rooms. That terrible loneliness that makes simple movements gigantic chores and weighs so heavy inside you that you cant answer a simple question with a yes or a no, or even shake your head. You cant even stare into inquisitive eyes. You can only feel the heavy loneliness flowing through your body and hanging wet and heavy on your eyes. They know nothing about these things.

Though the book needs this rhetorical perspective to achieve the compassion it aims at, cheating is still cheating.

It takes some cheating, too, to get in the best thing in The Room, a dazzling sado-masochist extravaganza that transforms the arresting officers into dogs whom the prisoner torture-conditions into suitably beastly perversions, which they then perform before a stunned audience of their own relatives and children in the prisoner’s imaginary laboratory. The episode, a central one, seems rather too inventive and witty for a mind whose other reveries run to screwing in the church choir, sending the cops filthy photos of himself with their wives, or entering into subliminally homosexual association with elegant and powerful gentlemen named Donald Preston and Stacey Lowry to rid society of police corruption and injustice generally.

Advertisement

Played more as horror-comedy, all this might be instructively amusing. But Selby’s presentation is essentially sober and earnest—the prisoner is evidently one of “the thousands who remain nameless and know” to whom the novel is dedicated, “with love,” and that love, however honorable its intentions, blurs the clarity of the human image it’s attached to. To make a dull mind interesting enough to be lovable, the novelist intrudes upon his own illusion, but by making the prisoner express what can’t be accepted as his own, the intrusions interfere with the credibility that precedes compassion. The Room is powerful and disturbing even so, but the boundaries of Selby’s art and moral vision are too large to be filled up by a single commonplace mind, psychopathic or not.

The boundaries of art are of course much under discussion in France these days, and in The Book of Flights J. M. G. Le Clézio crosses and recrosses them with contemptuous gestures toward the customs officers, though they haven’t arrested anyone in years. Le Clézio’s hero, Young Man Hogan, seeks to escape the oppressions of Western culture, especially language, traveling the world and enduring perilous tests in search of the truth that words have obscured. But of course the subtitle, “An Adventure Story,” is a joke—this adventurer has no fixed identity, the places he visits aren’t (for a while) very literal, nothing much happens. And of course the novel keeps destroying itself: Hogan isn’t the only narrator; poems, letters, and journal entries appear, as well as accurate “self criticisms” by the author and meditations by someone on Western and Eastern philosophy.

Even Childe Harold might find this Hogan embarrassing. He’s too charmed by noticing that from inside a bus the world seems to move while you stand still, too ready to admit the (in his case) all too evident truth that “I have everything to say, everything to say! I hear, I repeat!,” too interested by the thought that there are poems inside every head, that machines are alive, that every ball-point contains a novel. Le Clézio sees the objections to such romanticisms, but he can’t resist them either, and the interaction of the naïve and the ironic becomes a kind of self-indulgence, a way of being able to say whatever one likes without making up one’s mind about it.

I recognize that the roman nouveau rejects the idea that minds can usefully be made up, and of course it has a point, but the excitement of narrative indeterminacy seems to me to have lessened. Surely it’s rather late in the day for a novel to begin by asking, “Can you imagine that?” I’m less stirred than I used to be by hearing, after a fairly direct description of a town, that “It was in Italy, or Jugoslavia, or else Turkey. It was 1912, or else 1967, or 1999. No way of knowing.” (None at all?) When a writer asks, “How to escape fiction? How to escape language?” I mutter, “Why not try shutting up?” It’s like seeing a pretty girl rub off her make-up to show you her pimples.

As it proceeds, The Book of Flights subdues such nervous mannerisms and improves. Hogan leaves the Americanized West behind and travels into an Orient he and Le Clézio take more seriously (Hogan was born in Vietnam, we’re told, around 1939). And as we’re increasingly granted the illusion that we’re really there, and that “there” is somewhere in particular, the mood deepens. I must quote from a wonderfully sober and straight episode called “The Flute Player at Angkor,” where a simple enigmatic music induces in Hogan an apprehension of being, both Buddhist and oddly Wordsworthian, that is fully earned by the writing:

The music had ceased to be strange. It formed an integral part of everything, its sound issued clearly from the earth, the stunted trees, the old tumbledown walls. It gushed ceaselessly from the sky, floated along with the ball-shaped clouds, arrived at full speed with the light. There was no longer any reason to listen. Or to be far away. One no longer had ears. One was close, face to face with it. The music was long drawn out, no longer had an ending. It had never had a beginning. It was there, infinitely motionless, exactly like an arrow poised in mid-flight…. Where was all this happening? What was he going to do? The clouds move lazily in the sky, the stunted trees need water. Are there enough words for each of us? There is great joy, joy in the notes that soar and swoop, in the soft hissing, in the sharp trills. There is great fear, too, the voluble fear that furnishes silence. The earth is far away, as though viewed through the wrong end of a telescope. Is one on this side or the other side of the mirror?

“Are there enough words for each of us?” is a much better question than “How to escape language?” At a moment like this Le Clézio’s romanticism, no longer hung between youthful posturings and the equally youthful self-ironies that sustain and feed them, becomes serious and moving. By comparison, the fun and games of the anti-novel seems pretty shallow.

George Lamming’s Natives of My Person takes the form of a rather dated but solid historical novel (I suspect that Robert Graves is somewhere in Lamming’s mind), yet it records a history that never was on land or (in this case) sea. The ship Reconnaissance sails, without official clearance, on the triple passage from Europe to Africa to America and home again; but its anonymous Commandant takes on no slaves at the Guinea Coast, since he intends not to complete the voyage but rather to establish a free settlement in the New World, without obligations to the homeland and its compromising political and moral history. But while the decor and technology of Lamming’s story are consistently sixteenth- or seventeenth-century, the narrative is mysteriously out of skew with our history books.

The Commandant and (with one exception) his crew are natives of Lime Stone, a country torn with sectional divisiveness; the exception is the Pilot, Pinteados, a turncoat from Lime Stone’s great military and commercial rival, Antarctica. Lime Stone is governed and oppressed by an institution called (putting first things first) The House of Trade and Justice, the wife of whose corrupt Lord Treasurer is the Commandant’s old lover; she, it develops, has helped to organize the voyage and has sailed ahead with the wives of the crew to await their arrival at the site of the planned colony, San Cristobal (Colón?).

But the ship’s officers, Priest, Steward, Surgeon, and Boatswain, held by compromising ties to the old order, mistake or resist the expedition’s purpose, and two of them murder the Commandant during the Middle Passage, being then killed themselves by his loyal cabin boy. The crew, as bewildered as the reader, set off in the boats for San Cristobal, women, and a freedom they don’t quite understand, while Pinteados makes terms with the Antarcticans. The book ends with the women waiting for the Reconnaissance, ignorant of its awful fate yet somehow prepared for it, men being what they are.

Now all this sounds just dreadful, I know, and Natives of My Person is exasperating in more than its story. Lamming’s prose is portentous, hooked on simile, and anxious to suggest more than it says, inviting questions the story never answers. Why, apart from evoking the hard and the cold, “Lime Stone” and “Antarctica”? Why are so many of the crew named (in French or Russian) after New Testament characters? Why are some not so named? Can Lamming be serious when he calls (more than once) the officers’ last meal together their “last supper”?

Yet if reading Natives of My Person is a voyage into frustration and annoyance, Lamming’s story survives and grows in the mind afterward. As you learn not to ask the questions he seems to invite, not to interrogate names and events for some efficient correspondence between the novel’s world and ours, this imagined history reveals itself as a version of significances that “real” history is itself only a version of. Moral generality is a rare and dangerous aspiration for fiction, but Lamming’s thick, slow-motion prose is capable of achieving it, reminding one of Conrad’s successes as well as his indulgences. The best things here are the close-up portraits of well-intentioned minds under pressures that overbalance the available means of resistance, as in the Priest, destroyed for the service of the God he deeply believes in by seeing that he has served Him wrongly even though that was the only service possible.

On a larger scale the touch is less sure, but while Lime Stone and Antarctica can’t be simply identified in the terms of our history (as if that were somehow prior to all possible meaning), still their mutually supportive antagonism, and its effects on the people involved in it, is a helpful perception about the phenomenology of power in our world, past and present, and the Commandant’s effort to break free illuminates (for example) the complexities of Third World intentions without simply “meaning” them.

Certainly Lamming’s large perspectives preserve him from difficulties that many other black writers would have had with such material. The corrupting guilt of the slave trade, colonialism generally, hovers over this story of ruined new beginnings, and the Guinea Coast is the only exact point of tangency between its geography and ours. But if, as a West Indian, Lamming sees why the Commandant’s San Cristobal is situated in the Isles of the Black Rock, he also sees that the suffering of these “European” figures comprises his history even as the sufferings of his people, in the Middle Passage and after, comprise ours. The racial subject coalesces with other, sexual ones—just as Lamming transcends his blackness without forgetting it for a minute, so he transcends his maleness to write with intelligent compassion about the cross-purposes that bewilder men and women in their efforts to be themselves while understanding and respecting each other’s desires.

Natives of My Person is a hard novel to like, with excesses and longueurs that are very provoking; but I must grudgingly say that it finally succeeds in the pursuit of a seriousness that can be taken seriously.

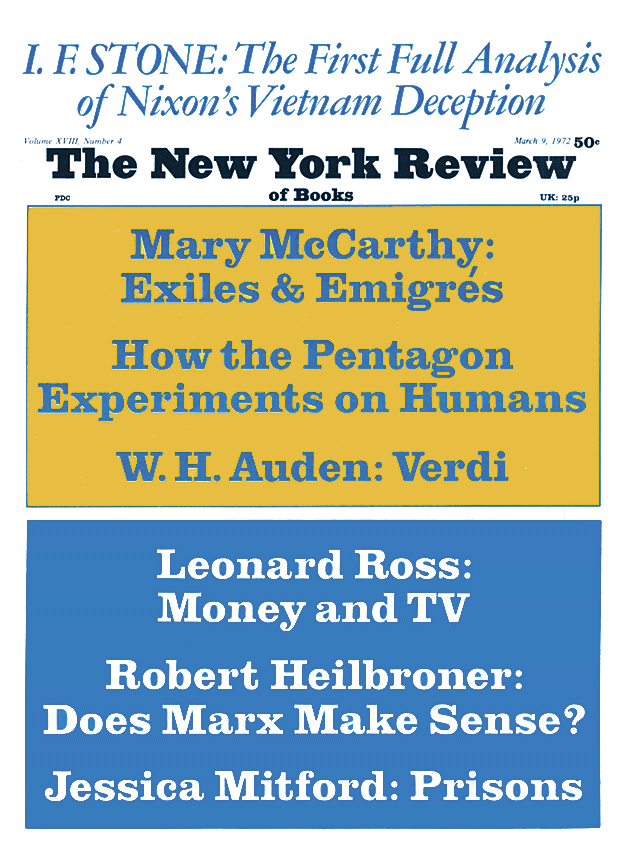

This Issue

March 9, 1972