Marx continues to brood over our intellectual life. In view of the immense impact that Marx has had on history, the fact would hardly be worth nothing were not his writing often so baffling. The famous historical essays and a few parts of Capital still have the effect of thunderbolts, but much of his earlier work, not to mention tedious chapters in the later volumes of Capital, are murky in a way that rouses both skepticism and impatience. That we nonetheless go on reading Marx, torturing ourselves by trying to penetrate the obdurate prose, can only be ascribed to a stubborn conviction that there is something of inestimable value beneath this opaque surface, if only we could discern exactly what it was.

At least in my own case, I now have a much clearer idea of that elusive Marxian contribution, thanks to a remarkable book, Alienation: Marx’s Conception of Man in Capitalist Society, by Bertell Ollman, a young professor of political science at New York University. For Ollman catches the crux of the difficulty in his very opening paragraph:

The most formidable hurdle facing all readers of Marx is his “peculiar” use of words. Vilfredo Pareto provides us with the classic statement of this problem when he asserts that Marx’s words are like bats: one can see in them both birds and mice. No more profound observation has ever been offered on our subject. Thinkers through the years have noticed how hard it is to pin Marx down to particular meanings, and have generally treated their non-comprehension as criticism. Yet, without a firm knowledge of what Marx is trying to convey to us, one cannot properly grasp any of his theories.

Why is Marxian language so opaque and batlike? The standard answer given to the student brave enough to raise the question is the “dialectical” nature of Marxian thought. Should the student be intrepid enough, however, to inquire: “And what is dialectics?” he is generally shoved off into the still deeper opacities of Hegel or Engels with their negations of negations, or asked to ponder over the famous triadic formula of thesis-antithesis-synthesis.

Ollman also solves the puzzle of Marx’s language by explaining its dialectic purpose, but what sets his book apart is that he has found a way of doing so that avoids—or rather, prepares the ground for—these baffling phrases. For Ollman has discovered a kind of Ariadne’s thread through the maze of Marxian linguistic problems in an element of dialectical thought that is usually overlooked or handled in an apologetic fashion, since it is radically at variance with the commonsense way in which we usually begin our philosophical analyses.

This disconcerting element is a relational view of the world. Such a view is very different from the nonrelational, particularist jumping-off point of normal discourse. To the ordinary person, reared in the tradition of Western empiricism, physical objects usually seem to exist “by themselves” out there in time and space, appearing as disparate clusters of sense data. So, too, social objects appear to most of us as things: land, labor, capital; the working class and the employing class; the state and the superstructure of ideas, philosophies, religions—all these categories of reality often present themselves to our consciousness as existing by themselves, with defined boundaries that set them off from the other aspects of the social universe. However abstract, they tend to be conceived as distinctly as if they were objects to be picked up and turned over in one’s hand.

But it is just this particularist way of looking at the world, according to Ollman, that interferes with our comprehension of Marx. For in Marx’s eyes, the basic “unit” of reality is not a thing but a cluster of relations. That is, the Marxian world (whose roots we can, of course, trace back through Hegel and Spinoza to Parmenides) is a web of relationships, extending through space and time, into which we can break only with difficulty, and whose isolated bits, physical or ideational, always contain within themselves the severed connections to other parts of the totality from which they were forcibly wrenched. Ollman cites Joseph Dietzgen, the first “Marxian” philosopher (a German autodidact little known in this country):

Where do we find any practical unit [of individuation] outside of our abstract conceptions? Two halves, four fourths, eight eighths, or an infinite number of separate parts form the material out of which my mind fashions the mathematical unit. This book, its leaves, its letters, or their parts—where do I stop?

I shall return later to the philosophical problem posed by this relational conception of the world, but I believe that Ollman is correct in insisting that only from such a viewpoint can we begin to make sense out of Marx’s dialectical language. For all the words that Marx uses in his treatment of capitalism or, for that matter, of history—capital, labor, value, the state—are batlike because each concept designates a complex set of relations embedded in a social matrix. For example, in capitalist society “labor” is a word that expresses both the essential productive activity of man and the “reified” form of that activity characteristic of a society in which labor has become a “commodity” (itself a multifaceted term); “capital” expresses both physical artifacts of production and an institution involving particular social relationships such as wage-labor; the “state” is a concrete set of law courts, legislatures, armies, etc., and an invisible web of class relations and ideologies.

Advertisement

Nor is this all. The relational view requires that we conceive the world, including its social elements, as more than a set of complex structures. We must also see it as a set of on-going processes. The word “capital,” for example, includes not only the relations we have mentioned, but also the ideas of accumulation and exploitation. Indeed, in the concept of capital we can even discern, in embryo, the destiny of capitalism.

This helps us to understand the idea of “law” in Marx. When Marx speaks of the “laws of motion” of capitalism, he means both those interactions that are immediately visible to non-Marxian social scientists, and the complex unfolding and working out of tendencies which the Marxian philosopher sees as an essential part of the realities he studies.

As a result of the multiplicity of meanings that lodge in his basic terms, Marx’s statements constantly appear to us as both perplexing and impossible, and at the same time suggestive and rich. The persistent attraction of Marxism, in the face of its confusing vocabulary, is thus evidence that Marx manages to assert himself by the reverberations of his thought even when his argument escapes us. Ollman’s contribution is to supply us with a means of tracing that argument by his analysis of the orchestral language that Marx uses.

Ollman’s book is called Alienation because he believes that the foundation of Marxian social philosophy is a theory of human nature. That is, the phenomenon of alienation, in its Marxian relational meaning, is not merely one of many attributes of life in a capitalist setting, but is the very touchstone through which the deepest and most obscure aspects of our existence become manifest.

What is the Marxian theory of human nature? It is very unlike the kind of theory that we would erect on the foundations of contemporary psychoanalytic or anthropological knowledge. Marx is interested in the “nature” of man in a relational rather than particularistic fashion, which is to say that he is concerned with the twin existence of man both as a biological creature and as a social being. As a biological creature, man shares with every other living being certain “powers” (or abilities) and certain physical needs; but in addition to this substratum of man’s “natural” nature, there is wedded to man his “species” nature—that is, a set of powers and needs peculiar to his existence as a human being.

What are these two sets of powers and needs? The biological substratum is left largely unspecified by Marx. It corresponds, Ollman suggests, with everything in man that is not distinctively “human,” a definition which it is not easy to flesh out. Presumably Marx conceives of natural man as a bundle of drives, instincts, sensory and manipulative capabilities, a creature endowed with animal powers of perception, reflexes, and the like. It is here, of course, that a critique of the Marxian vision begins, as we shall subsequently see. But it is species man, not natural man, that fascinates Marx. Man becomes human in so far as he uses his natural powers and needs differently from animals, injecting them with the mysterious attributes of self-consciousness and the imperatives of belief. For example, as Ollman points out, sexual activity as a natural power is an activity that man shares with all living things, but the manifold ways in which he treats women (or in which women treat men) is a specific human attribute of sex capable of innumerable variations.

Moreover, man’s truly “human” nature lies not only in this differentiation of his natural functions from those of sheer animality, but also in the developmental capabilities of those functions. As Ollman writes with regard to the sexual function, “Marx believes that when women are accepted as equals, possessing the same rights and deserving the same thoughtfulness as males, then man’s sexual activity is no longer that of an animal; sexuality will have been raised to the level of things peculiarly human.”

Three principal relations connect man’s natural being with the world and thus offer the avenues for his species development. The first of these is perception—the process by which man becomes aware of the existence of nature and of himself. The second is orientation—the process by which he “makes sense” of the world he perceives. The last is appropriation, or the use to which man puts the perceived and understood environment. The richer and more fully developed the human being, the more of his environment will he “appropriate,” not in the narrow sense of exerting a claim of ownership over it, but in the deeper sense of incorporating within his own being aspects of the world to which a less developed human will remain indifferent. Thus, in the goal of an ideal communist society, men will appropriate life as poets do, making part of themselves the smallest as well as the largest marvels of existence, until in Marx’s words: “Man appropriates his total essence in a total manner, that is to say, as a whole man.”

Advertisement

We shall look more carefully into the conception of an ideal communist society, but it remains now to trace the consequences of the Marxian conception of man. Here we enter more familiar ground, as we follow the social evolution of man from his “original” state through a long process of historical conditioning to the final goal of full humanity—a hegira which begins and ends in a social relationship that is communal, classless, stateless, and intensely personal, but whose origin and terminus are separated by the immense gulf of technical and intellectual development that distinguishes fully realized man from primitive man. In this process, whose misty beginnings we can vaguely discern in the first division of labor in early agricultural settlements, the central theme is the progressive and changing process of the “alienation” of man, a process that does not begin with, but that attains its most exaggerated and historically significant form in, that socioeconomic formation we call capitalism.

What is this pervasive alienation? Walter Weiskopf, in a well-received recent book, Alienation and Economics, describes it as a condition whose ultimate roots lie in the inescapable duality of the brute fact of human existence and the self-knowledge of human existence: “Through his consciousness,” writes Weiskopf, “man is alienated from the world and his world is alienated from him.” This leads Weiskopf to conclude that alienation cannot be completely eliminated. “Being human,” he writes, “is being alienated. Under no circumstances can man accomplish an existence in which he can actualize all his potentialities…. Renunciation and its inevitable consequence, suffering, are essential characteristics of human existence.”

Weiskopf postulates the inescapable presence of existential alienation as a prelude to discussing social alienation, which is caused by the particular forms of repression and deformation imposed by the changing institutions of society. His interesting book, which recalls Marcuse’s work, thus becomes both a description and a denunciation of the extraordinary repression of Western civilization with its reduction of reason to reasoning, its derogation of values as nonscientific, and its systematic constriction of spontaneity before the demands of organization.

Marx sees alienation in a different light. To him, alienation is not an inherent aspect of human existence but rather a condition from which man suffers because he has not yet attained the full “species powers” that he is given. The conflict of existence and consciousness which Weiskopf sees as the ineluctable core of alienation does not enter the Marxian view, in so far as the human acts of perceiving, orientating, and appropriating the world do not imply an impassable breach between man and nature, but a bridge by which men may find a unity with nature. To Marx, the truly human man merges himself with the external world by internalizing it.

What, then, is alienation to Marx? As Ollman puts it: “Alienation…is used by Marx to refer to any state of human existence which is ‘away from’ or ‘less than’ unalienation.” More specifically, alienation refers to the ways in which man’s “species powers” of perception, orientation, and appropriation become stunted and crippled by the pressures of economic society. To quote Ollman once again:

The distortion in what Marx takes to be human nature is generally referred to in language which suggests that an essential tie has been cut in the middle. Man is spoken of as being separated from his work (he plays no role in deciding what to do or how to do it)—a break between the individual and his life activity. Man is said to be separated from his own products (he has no control over what he makes or what becomes of it afterward)—a break between the individual and the material world. He is also said to be separated from his fellow men (competition and class hostility have rendered most forms of cooperation impossible)—a break between man and man. In each instance, a relation that distinguishes the human species has disappeared and its constituent elements have been reorganized to appear as something else.

Thus alienation is to unalienation as disease is to health. To put it differently, one might say that alienation is a human disease whose symptoms consist in the fracturing of “human nature” into nonhuman parts, each of which becomes elevated to the status of an autonomous aspect of “life.” Thus we have labor rather than work; commodities rather than the useful objects of human effort; classes and nation states and even “society” rather than the direct interaction of man and man. It follows as well that what Marx means by communism is the healing of man by reuniting these fragments in a social setting in which the abstractions and figments of alienated life will disappear like the wraiths they actually are.

This conception of alienation takes on additional meaning in the light of the relational point of view that Ollman stresses. For we can then see that the word “alienation” means to Marx not only the relations between man and his work, or man and other men, but also the process through which human nature realizes itself. Just as the concept of capital contains the idea of the destiny of capitalism, so the concept of human nature contains the idea of the destiny of man, which is his history. Man thereby suffers from the condition of alienation to the extent that he has not yet fully realized the potential of his being.

Marx directed his main analytic attention, as we know, to that phase of history called capitalism, at once a great step toward man’s self-realization and a terrible prison preventing his further progress. For under capitalism the phenomenon of alienation appears in a peculiarly exaggerated and yet curiously veiled fashion, reaching its heights in what Marx called “the fetishism of commodities”—the strange belief that prices represent the relationship between things rather than between men.

It is this central role of alienation under capitalism, both as a social condition and as a phase in the historic process of human development, that also makes the labor theory of value so critical in the Marxian scheme of things. For the labor theory, however unsatisfactory as a means of explaining prices, is indispensable in explaining a question that conventional “price theory” does not even consider: How does it happen that labor, which in many societies is not for sale, has a price—a value—under capitalism? Thus, the labor theory of value plays its all-important role just because labor is the “stuff” in which capitalist wealth is measured, in contrast to the political power, royal blood, religious charisma, or hunting prowess that constitute the coin of the realm of differently constituted societies.

I shall leave undiscussed the remainder of the book, in which the concept of alienation is traced in greater detail through man’s relation, under capitalism, to productive activity, to his fellow man, to commodities, classes, the state, religion. All this is reasonably familiar and brings few surprises. But what continues to invest with interest even this much worked over subject is the freshness that springs from Ollman’s constant emphasis on Marx’s relational use of language as the key to the dialectic character of his thought. For what Professor Ollman has provided, above his substantive contributions to the interpretation of Marx, is a translation of Marx from the obscurities of his ill-understood language into terms that present the complex intention of his thought in words that are no longer bats.

What remains is to place this clarified re-creation of Marxian thought in a critical perspective. And here Ollman again proves to be an excellent guide. For he has accurately placed the two pivotal elements in Marx’s thought. The first of these is the fundamentally “religious” nature of Marx’s view of man. As Ollman points out, Marx’s ultimate conception of man is beyond empirical demonstration; it is a declaration of belief for which no evidence is available. In Marx’s view, man is a creature of immense latent abilities, Promethean ambitions, and vast capacities for adaptation. This is not an optimistic view of man so much as a devout one, and like all such devotional statements—as well as statements to the contrary—beyond proof.

Marx asks us to believe that natural man—that bundle of all that is not species man—can coexist in perfect harmony with species man with all his bundle of social relationships, if the social environment no longer imposes the deforming conditions for which capitalism (perhaps Marx would today add industrialism) is responsible. Is this a fantasy? Is the idea of “unalienated” man, either in primitive or sophisticated communism, anything but the secular version of those wish-projections so patent in theology? Freud would surely call it a fantasy, as would Weiskopf, following in Freud’s footsteps.

Although Ollman does not use the word “religious,” it should quickly be said that he is fully alive to the element of faith in the Marxian view of human nature. “Are the changes which occur in [man’s] character always rational?” he asks. “How long does it take for new conditions to produce new people?” Indeed, by introducing considerations of generational lag and of character structure, he adds an important element of depth psychology which, while not ruling out the Marxian hope, rescues it from the shallow millenarianism that has made so much “Marxian” prophecy ludicrous. Ollman asks only that the question of man’s potential be left open. Some degree of human perfectibility, some progress toward a state of unalienation, is surely possible, he argues. A vision of unalienated man may be needed to help us to escape from the particular forms of alienation in which current institutions entrap us.

What Ollman does not ask is another and, to my mind, more searching question. It is whether the idea of unalienated man—of man in the full glory of his perfected being—is finally a benign conception of mankind. A single great leap from alienation to unalienation—a leap that Marx believed would occur when the social conditions of capitalism were completely removed—raises hopes for instant salvation that the inertial elements of the human personality can all too easily turn into despair and bitterness. But even the idea of de-alienation as a never-ending process has its dangers. However indispensable as a stimulus for men seeking to free themselves from harmful thralldoms, the quest for perfection ignores another human need—the need for solace. There is a Sisyphean aspect to the endless pursuit of the unalienated state that not only threatens to push exhilaration into exhaustion but lends itself all too easily to zealotry and fanaticism.

Equally in question is a second fundamental element of the Marxian philosophy. This is the Marxian emphasis on the relational nature of “things.” Ollman is fully aware of the debatable aspect of this proposition and of its rejection by most contemporary philosophers. What he believes, and argues for cogently, is that the relational view can hold its own alongside that of particularism and individuation. I would even go a step beyond Ollman here. Just as the human mind has the curious ability to see two-dimensional drawings in three dimensions, and then to have the third dimension reverse itself—the cube now coming toward you, now going away—so the mind is able to picture the outside world as composed both of individuated entities and interrelated wholes. Indeed, with one perceptual process as with another, we are often unable to prevent ourselves from organizing “reality” in ways that we know are mutually incompatible.

I would suggest that a philosophy of dialectical relations such as Marxism is one such way of comprehending social reality, and that it must be accepted, together with the opposite particularist view, as among the modes by which we manage to organize the assault of data on our minds. As such, it is neither better nor worse than the particularist view, but another powerful and fruitful way of comprehending things or, as Marx would say, of “appropriating” them.

Moreover, I would insist that the relational way is just as useful and important as the nonrelational for another reason. It is to urge the same open-mindedness upon Marxian philosophers as Ollman would ask of non-Marxian thinkers. For there is one tendency of Marxism to which Ollman’s book pays little heed, no doubt because he believes it to be only an excrescence on Marxian thought rather than an inseparable aspect of it. This is the tendency of Marxists to pass from philosophy to theology, in its worst sense, arrogating to their views an infallibility and exclusivity that change the suppleness of a relational philosophy into the brittle structure of dogma.

Marxism has no claim to be, and surely is not, the only mode of comprehending reality, including that aspect of reality on which it sheds a more vivid light than any other, namely, the historical and existential nature of capitalism. Perhaps one of the most salutary effects of Bertell Ollman’s brilliant and illuminating book is to prove that an intolerant religiosity is not a necessary characteristic of Marxist thought. Marx himself once said that history repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. For Marxism to retrace the depressing early intellectual history of theology would be, alas, to prove the dictum in reverse.

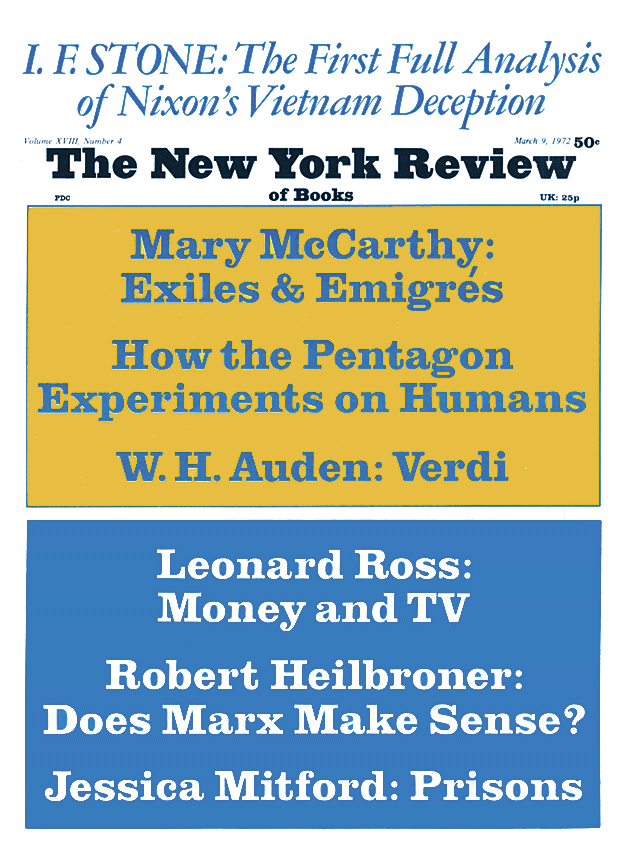

This Issue

March 9, 1972