Recovered psychiatric patients don’t usually write about their experiences in and out of the hospital, but enough of them have done so to make a tradition of sorts. One thinks of A Mind That Found Itself, written by Clifford Beers in 1907; or Fight Against Fears, Lucy Freeman’s dramatic account of her troubles—a bestseller in the middle 1940s, when psychiatry was catching hold among the middle and upper American bourgeoisie; or more recently, Barbara Field Benziger’s The Prison of My Mind, from which the reader learns how the rich can be hoodwinked and devastated by the seamier side of medicine and its various specialties—all those “rest homes” and “sanitoria” with their pretty names, set up to fleece patrons, whom they insult and humiliate, then quickly discharge when cash runs out or suspicions (no doubt called “paranoia”) get dangerously active.

Then there are those who don’t recover. They start out with something that is called “anxiety” or a “phobia” by the family doctor. With his help they struggle against their symptoms for a time, only to feel worse and worse. If they are reasonably well-to-do and educated they are likely to take themselves to a private psychiatrist. If they have little money but are students or young professional men or women they may go to a clinic, where their youth and “promise” earn them favored status—“individual psychotherapy.” If they are poor or their parents are working people—mechanics, gas station attendants, waitresses, switchboard operators—the chances are that “medication” will be prescribed, infrequent and brief “follow-up” visits recommended, and maybe, under the best of circumstances, some “group therapy” made available.

In 1958, August Hollingshead and Frederick Redlich in their study Social Class and Mental Illness concluded that money commands attention from psychiatrists, among others; those who are relatively poor or uneducated (meaning millions and millions of ordinary working people, who can barely pay the baby doctor for the routine childhood illnesses that come up, let alone bills for psychotherapy) are commonly treated in ways that require much less of the doctor’s time. In the fourteen years since their book appeared, nothing has happened to change their description.

Yet here, as in so many other respects, psychiatry has to be distinguished from other branches of medicine. Nowhere in this country, or in any other country, do the rich and powerful fail to get better “care” than the poor. Hospitals vary, as does nursing care or the quality and quantity of medical attention, according to the patients’ pocketbooks or positions in society. (Since Hippocrates, the call for another, more equalitarian approach has been given unremitting lip service.) Yet whether a patient is rich or poor, penicillin is prescribed for bacterial pneumonia, surgery for an inflamed appendix; class barriers have nothing to do with the way children are protected from polio or tetanus—the same vaccine is used throughout the country.

In contrast, psychiatrists talk about various “modalities of treatment,” supposedly a rational response to separate “clinical entities,” whereas in fact different patients, possessed of the very same “difficulties” (or “illnesses” as they are mainly called, an arguable use of medical imagery), receive thoroughly different kinds of “therapy” (in psychiatry, where irony and mystery if not mystification abound, quotes around words are not a temptation, but a necessity). One patient with the diagnosis of a severe “phobic disorder” or, perhaps more ominous, “border-line schizophrenia,” is called “treatable,” seen two or three times a week with what some of Freud’s patients called “the talking cure.” Another patient, similarly diagnosed, is pronounced “a poor treatment case,” maybe especially “resistant” to intervention, or “unmotivated,” an “undesirable candidate for psychotherapy”—to draw upon a phrase that I used to hear over and over again when I was a resident and, damn fool that I was in those calm Eisenhower years, never once thought to question.

Psychiatric terms, apparently so clear-cut and emphatic, have extraordinarily versatile lives: they come and go, blend into one another, are used by one doctor, scorned by another. More dangerously, they can have subtle and not so subtle moral or pejorative implications. “Good” patients, liked by their doctors, are described one way, “bad” patients, whose mannerisms (maybe just plain manners) or “attitude” or deeds are found to be unattractive, are described differently.

The difference is one of tone, emphasis, and, always, choice of words, many of them as portentous as they are slippery. This youth is “obsessive,” but much of his behavior is “egosyntonic,” and his primary struggle is “oedipal,” even if his “defenses” are by no means adequate, and sometimes shaky indeed. Another youth is also “obsessive,” but underneath are serious “pre-oedipal” conflicts. Furthermore, his defenses are “primitive,” and he may well be a “border-line case.” With additional exploration we might even discover an “underlying psychotic process.”

Advertisement

Needless to say, the very same youth can be seen by one psychiatrist, then another, and on and on, with a similar divergence of opinion. X-rays do not affect the diagnosis. Blood tests cannot establish without doubt what has to be done. We are in a world of feeling, the doctor’s as much as the patient’s, so no amount of training or credentials or reputation can remove the hazards of such a world: inclinations of various kinds, outright biases, blind spots. I do not deny the enormous value that a personal psychoanalysis has for a future psychiatrist, or the effect years of supervision can also have. By the time most psychiatrists have finished their long apprenticeship they do indeed tend to know what kind of patient they work well with, what kind of patient they ought to avoid, and most important, what their vulnerabilities are.

Still, such awareness isn’t always translated into wise clinical decisions. Patients are accepted who ought to be referred. Patients are treated one way, when perhaps another tack might make things a lot easier for both them and their doctors. And even when in a particular case things do begin to work well, “life” is always to be reckoned with. Not everyone can keep at therapy or analysis for those months that have a way of becoming years. There is a job to hold, and it might require a move. There is the draft. There are unavoidable accidents or emergencies that come up from time to time.

From the other side, a similar range of disruptions may arise: the doctor decides to move, or is in training, and so leaves one clinic or hospital for another; he may decide to switch from “practice” to more teaching and research; he finds that his private patient no longer can afford his fees, hence is to be referred to a clinic. It is no doubt painful for many of us to think very long about that last “factor,” but it is not an uncommon one, and is yet another reminder about the nature of our society—psychiatrists make themselves available to those whose position in the world enables the purchase of the special kind of intimacy provided by the doctor-patient relationship.

Nor can the implications of such an arrangement be completely forgotten, by either the one who pays or the one who receives the money. Expectations and, later on, demands are backed up by expenditures, and payments establish for the man or woman who receives them their own mandate—while week after week two individuals are talking about the most extraordinarily personal matters and developing between themselves honest and, it is hoped, sustaining exchanges. As well as those “transferences” and “countertransferences” that measure our unfailing ability to find targets for our irrational strivings in those we meet and spend time with (and also, at one remove, in the books we read and the authors we occasionally lavish with praise or feel ourselves inexplicably turning against).

Obviously some of these issues are almost infinitely complicated; they have to do with how various human beings get on and, just as important, the subtleties of class and even caste (some would insist, thinking of patients in mental hospitals) as they affect the lives of both psychiatrists and patients. Once in a while, though, generalities and difficult arguments come into especially clear view for both psychiatrists and patients through the medium of a particular, concrete event.

James Wechsler’s In a Darkness provides such an occasion. The reader knows from the beginning that unlike Clifford Beers, Lucy Freeman, or Barbara Benziger, Michael Wechsler, son of James and Nancy Wechsler and brother of Sally Karpf, committed suicide at age twenty-six, after a long and stormy series of involvements with no fewer than eight therapists, whose offices are scattered over Boston and New York, which, incidentally, contain the heaviest concentration of psychiatrists in the world.

Mr. Wechsler is a well-known journalist; he is now editorial page editor of the New York Post. He has written his book with the help of his wife and daughter. They have wanted to look back and ask themselves questions which they know ought to be asked, not because they are laboring under “grief reaction” and need “catharsis,” but out of respect to their rights as intelligent and sensitive human beings who have gone through a saddening, at times harrowing, experience. They do not want to leave unexamined the many circumstances, moments of crisis, tragic as they turned out, which they and their son went through from the spring of 1960, when the boy, then in the Fieldston School at Riverdale, New York, first felt the need to see a psychiatrist, until the spring of 1969, when his parents found him in bed and without a pulse, and rushed him to a nearby hospital, where he was pronounced dead, a victim of an overdose of barbituates.

Advertisement

The book is short and unpretentious. Mr. Wechsler wastes no time in eulogies, nor has he any desire to use his considerable skill as a writer in order to achieve the kind of self-justification it would be only human for him to want. Rather his effort is to describe, from his and his family’s point of view, a certain progression in the short life of a bright, sensitive, gifted youth, whose parents’ emotional, social, economic, and political resources, however substantial, were in the end not enough to save his life—and when one says that, one must immediately make it clear that Mr. Wechsler has been moved to write this book and give it the title he has because he does not know to this day what would have been enough, what was needed to save his son’s life.

Still faced with “darkness,” the mystery and confusion that he as the father of a severely troubled psychiatric patient could never somehow escape from, Mr. Wechsler has written a book of great narrative power which will doubtless unnerve his readers (notably the educated lay public, but, I would hope, also the psychiatric profession itself).

Michael Wechsler was apparently a “normal” boy and youth until he was seventeen and a senior in high school. That is to say, he got along reasonably well with his family, was a first-rate student, had a number of good friends and a fairly active social life. He had presented no real problems to his parents as he grew up, and so they were taken aback when he asked them for the money to see a psychiatrist. Why? For what “problem”?

They would not easily find out, not then and, to some extent, not ever. They agreed to pay the bills, beginning with Doctor First. (Mr. Wechsler calls the doctors Dr. First, Dr. Second, and so on up to the last one, Dr. Eighth, which serves to dramatize the disruptive and bewildering aspects of the experience for both the patient and his family. Names like “Brightlawn,” “Fairhope,” “Grace Hills” are given to the five institutions in which Michael Wechsler spent a total of twenty-six months, which further evokes the kind of bitter irony and enigmatic fatefulness that Kafka felt drawn to.)

So it began, an awful journey for the young man and no less so for his family. At first things went reasonably well, even if there was considerable trouble between Dr. First and Michael’s parents. When Michael was accepted by Harvard, the psychiatrist pronounced himself worried about his patient, but said that there had been progress, and certainly there was no need for the young man to hesitate about going up to Cambridge. In no time Michael was seeing Dr. Second in Cambridge, and because they didn’t get on well, Dr. Third was brought in, with the blessings of Dr. First, to whom Michael had been quite attached.

The first year at Harvard is hard for many of the bright, earnest students who come there, with so much talent and so much self-consciousness about their supposed superiority. On the other hand, some strong and ambitious students quickly see the college as a place whose opportunities ought to be seized. Michael set to work, tried to keep up with the fast pace around him, and in time developed a strong interest in psychology—the experimental kind, meaning the possibilities in pigeons rather than the unconscious dynamics of human beings. He mainly kept to himself. He was shy and rather nervous, though certainly in that respect not much different from many of his classmates. Nor were his visits to the two psychiatrists at all remarkable; the Harvard University Health Services operate a much visited psychiatric department, staffed with a dozen or so doctors, and nearby are the private offices of more such doctors, some of whom spend most of their time with students.

The first year at Harvard went by, and the second, without too much difficulty. The Wechslers knew Michael was in trouble, but they kept hoping, as parents do, that somehow the turmoil and moodiness would go away. Instead, things began to get worse. Michael fell asleep at the wheel, was declared “accident-prone.” Then he got a motor bike, and was nearly killed when he collided with a bus. In fact, the bus driver would eventually insist that the fault was his, he had suddenly taken a wrong turn.

But by then both Michael and his parents were well down a road all too many people have traveled: their every move was subjected (by them and by the doctors, one after the other) to a scrutiny so close that at times it became utterly self-defeating, because what was intended to clarify became a new source of anxiety and despair. When everything is so closely watched, when events are turned over and over, so that their “significance” can be appreciated, when psychological “meaning” is attributed to everything a person does, then awkwardness and self-consciousness become a fact of life—become life itself. A bus driver’s mistake is taken as evidence of a patient’s deterioration and his parents’ negligence, if not outright wrongdoing, because they paid for the bike.

Anyway, Michael’s condition did not substantially improve, in spite of the “help” he was getting. Young patients often simply outgrow the kind of self-centeredness that prompts psychiatric treatment—if they don’t, they are likely to be headed for a long stretch indeed with the doctor. Michael grew more and more inward, cut off from friends and family. He continued at Harvard, had some good moments, but by his junior year was in worse shape than ever before; he flunked his examination in psychology and soon thereafter was admitted to the university infirmary because he had swallowed a large number of pills.

The next step was a mental hospital, the first of six such episodes in the course of the following five years. At that point, in the chapter called “The First Mental Hospital,” Mr. Wechsler’s book gains momentum. The earlier uncertainties are now gone, and the author is free to show the reader directly how things went—downhill all the way. Everything is there: the rituals that a mental patient and his visitors have to go through in the hospital; the inscrutable faces, the rudeness and vulgarity, and occasional stupidity, of some doctors; the warmth, decency, and intelligence of other doctors; the banalities that psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers use—not necessarily out of malice, but because, they, too, are in the dark, and so find refuge in clichés and a certain calculated impassivity, the more insulting and harmful because they are clearly meant to stifle questions, let alone objections.

There are also the disagreements—between one psychiatrist and another, between the hospitals, the first one in Massachusetts, the others in New York; and the grim and sad life in Manhattan’s East Village, where drugs overwhelm already vulnerable young people, no small number of them just out of or just ready to enter mental hospitals. Finally both patient and family get desperate as bad becomes worse, as doctors are given up for yet more doctors, as new “therapies” are suggested, tried, found wanting—so that all too soon hope recedes for good and everyone is content to hold on for dear life, knowing that the outcome of even such a day-to-day struggle can by no means be taken for granted.

Psychiatrists and the institutions they run are no less susceptible to sham than other professional men and other institutions, and Wechsler has a sharp eye for their hypocrisies. Anyone who has gone through psychiatric training in the Northeast will have little trouble recognizing the hospitals described and, for that matter, the not unrepresentative array of doctors presented. So will many patients with Michael Wechsler’s upper-middle-class background and education. The author is sometimes unfair to his son’s doctors, some of whom were and no doubt are as desperate as he was and is for the answers that might spare future young people and their parents the “darkness” this book documents. But his is a thoroughly restrained and thoughtful analysis, not without its moments of grim humor:

As we pursued this inquiry, we heard many favorable comments about another state hospital that had the incidental but appealing advantage of being located in the borough in which we lived. When we proposed it to the resident, his response was enthusiastic but he warned that it was extremely difficult to gain admission. Its prestige, however, was a major asset in convincing Michael of its desirability—he, too, had heard respectful comment about it through the patient grapevine. With his acquiescence assured, we exerted all available influence and we hailed the news that he had been accepted with some of the same delight we had felt when Harvard opened its doors to him.

Mr. Wechsler also describes the social workers who say, without expression, only “How do you feel?” or “What are your feelings about that?” One wants, at the very least, to tell them to come off it. To do so, however, would be to exhibit “hostility,” just as a patient has to watch out, too, lest he or she be accused of “acting out.” There are good reasons for social workers to keep in close touch with the relatives of hospitalized psychiatric patients, and beyond any doubt the intense feelings that psychotherapy can generate do indeed spill over from the doctor’s office to the home, the job, and, in this instance, to the hospital ward.

Nevertheless, what Mr. Wechsler objects to and satirizes is something else—the heavy self-righteousness that the parents of a troubled child are especially apt to experience at the hands of certain “mental health professionals,” as they sometimes call themselves. It comes across as a mixture of rhetorical phrases, thinly veiled accusations, and galling (because inappropriate) self-confidence. They seem to be telling one in a manner of almost absolute cool (one never gets excited, that is “neurotic”) how everything must be: you’ve made your mistakes, let’s face it, and even today you are compelled to repeat them, we know it, so we are the ones to take over now; and meanwhile, don’t get in our way, don’t go beyond the limits we in our knowledge (if not wisdom) will set, and let us do this and that—after all, he or she is without question suffering from X, maybe with a touch of Y.

Before he died Michael Wechsler saw psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, men-doctors, women-doctors; he received insulin, drugs, electric shock treatments; he had occupational therapy, a good deal of it; he was seen in private offices, on hospital wards, in clinics associated with important and well-known hospitals. Beyond question he came under the care of first-rate physicians, well-trained (even well-known) analysts; and he was a patient in America’s “best” (teaching) hospitals. To add to the complexity of his case, he clearly was not as disturbed and overwhelmed as other “schizophrenic” (the diagnosis he eventually got) patients become in the course of what is one of the cruellest and most enigmatic states of mind or being man can fall prey to.

I refer to a “state of mind” because even though Mr. Wechsler keeps on calling his son “sick” and “ill,” and even though the president of the National Association for Mental Health has told him that his son Michael’s affliction is the “number one health problem in the world today,” there are good reasons to hold off using that kind of medical imagery. Schizophrenia may indeed have its origins in faulty genes, in some neurophysiological or biochemical disorder we have yet to understand. But right now we know that it is a word meant to describe the way some people have come to live with themselves and others—they think and feel and often enough act in ways that to some degree distinguish them from the rest of us.

Why do they do so? How has it come about that they do so? For precisely what psychological (let alone genetic or somatic) reasons? These are questions best acknowledged as unanswered. Why does one youth, brought up by decent, kind, and attentive parents, become schizophrenic, whereas another who grows up among narrow-minded, stingy, even brutish parents pays a price for it but never goes crazy, never sets foot in a mental hospital, has no desire to commit suicide, is called “normal” by the rest of us—and by no means has to turn into a replica of his or her parents?

Psychiatric formulations can help to clarify what happened to those “in trouble”—else why have they gone to the doctor? In retrospect those doctors come forth with explanations, but child psychiatrists know how hard it is to single out exactly what is truly pathological and apt to remain so, as opposed to a particular child’s way of growing up and coming to terms with himself or herself. They are correctly loath to predict the psychological future even of the upset children they do see, never mind those millions and millions who have no reason to go near a child guidance clinic.

When things go wrong with a grown-up or a child, everything that has happened or been said becomes potentially significant, as engrossed doctors labor hard to understand what they see and hear; and often the pieces just can’t be picked up and put together—just as, when things are working well in a person’s mind, no one notices the dozens of idiosyncrasies and blind spots (“neurotic character traits,” some psychiatrists would call them) that we all have and that assume such importance only when we being to get into “emotional trouble.” In the face of such uncertainties and ambiguities, modesty on the part of psychiatrists and a certain hesitation to talk about “diseases” and their “causes,” as other doctors are wont to do, might even be “therapeutic” for beleaguered patients and their relatives, who deserve more than nervously authoritative fiats, and for those clinicians who have to contend with what are, finally, life’s complexities.

Mr. Wechsler explains why he was moved to write In a Darkness:

Indeed, if there is a single message in these pages, it is that those who see in Michael some resemblance to someone they love resist being intimidated by professional counsel and place some faith in their own instincts. This is not to derogate the need for such counsel—too many are denied it for lack of private means or public resources—but, rather, to warn that it may often be conflicting, confusing, and stifling.

He does not repeat that assertion, but rather lets his account make the case: the changes from one doctor to another, one hospital to another, none of them initiated by the Wechslers; the assertions and counterassertions handed down; the conflicting philosophies of treatment recommended; and perhaps most unsettling, the snide remarks made about each other by professional men and women. Nevertheless, the author seems to know that however justifiable the resentment he and his wife have felt, the real tragedy was a condition, a state of affairs in which they were each one of them caught up—not only Michael Wechsler and his parents, but also the long succession of doctors and nurses and fellow patients to whom the young man turned and from whom he drifted away.

Perhaps no one could have “saved” Michael Wechsler, which means helped him to shake off the suffocating grip his moody, self-lacerating side had gained. Yet, even though I do not fault the author’s right to be severely disappointed with several of the doctors his son saw (the words and phrases reported ring completely true to my ear), I found myself thinking of what we do know, what many dedicated therapists have been able to accomplish over the years since psychiatry has become such a prominent part of American life.

One of the hardest things about being a psychiatrist is the terrible discrepancy between what is understood and what can be done. I really do think that several of those eight psychiatrists knew a lot more about Michael, understood him far better, than they could possibly reveal to his parents even if they had the time or wanted to. They were doubtless haunted as any clinician is by their task: how to translate analytic vision into therapeutic action that works. Maybe the dogmatism, the gratuitous self-assurance, the rigid insistence on rules of conduct or treatment reflect not so much the anxiety doctors feel when they know deep down how much they don’t know, but the despair a clinician feels when he realizes how much needs to be done and how hard it is to do—how uncharted, sometimes unsatisfactory, and occasionally hopeless therapy can be.

Maybe, too, several of those eight doctors were haunted by an awareness of the extraordinarily impressive example analysts like Harry Stack Sullivan, Frieda Fromm-Reichman, Harold Searles, and Gertrud Schwing have set for the rest of us. Anyone who has read Sullivan’s Schizophrenia as a Human Process1 or Fromm-Reichman’s Principles of Intensive Psychotherapy2 or Searles’s brilliant and unashamedly self-scrutinizing Collected Papers on Schizophrenia and Related Subjects3 or Schwing’s A Way to the Soul of the Mentally Ill4 can only realize the demanding and exhausting nature of the work such therapists do—but do do, day in, day out, and sometimes with astonishing results. Years of patience and persistence are required, and a special temperament. Many doctors simply cannot take to such work, or stay with it, managing the delicate balance of firmness and flexibility, of openness and self-containment that seem so welcome and healing to the kind of patient Michael Wechsler was.

We will never know what actually happened between Michael and the eight doctors he saw, but especially in Harold Searles’s book (which is written for his colleagues rather than the general public) one learns how men and women far more disturbed than Michael Wechsler ever was were treated—and with eventual success. The patients’ families were not told to stay away or regarded as outcasts. Nor were the patients themselves asked to endure the doctor’s studied aloofness or silence, his “neutrality,” his unwillingness to talk about himself, about his own worries and fears, and even his “needs”—including those that made him become a psychiatrist in the first place. If bitterness and resentment and various disappointments were seen as “problems” for those Dr. Searles worked with, then love, too, was acknowledged and appreciated as well as “analyzed”—including not only those childhood love affairs we all have experienced but also the respect and affection that may take place between a doctor and a patient, by no means all of it “irrational” or “neurotic” or adequately conveyed by the use of clinical terms like “transference” or “counter-transference.”

I write this aware that it is no solace at all to mention those books, those especially resourceful therapists—who, tough as they have to be, seem virtually inspired, graced with miraculous qualities of mind and heart. If only, one is saying, and if only, James and Nancy Wechsler must continue to think. Still, they themselves wanted to share their experience so that others might be spared needless suffering, even as Frieda Fromm-Reichman tried over and over again to tell her colleagues to take a stand against various rigid attitudes and policies, all in the hope that patients one shunned or wrongly approached would no longer be so condemned.

One can only keep on hoping that every young psychiatrist-in-training will read carefully what James and Nancy Wechsler saw and felt, and never forget the lessons they have suffered to learn. Were at least some of those doctors to do so, I believe Michael Wechsler’s fine, compassionate spirit, which continues to press itself on his parents and comes across so movingly in his poems and letters, would find itself significantly affirmed—and that particular kind of redemption, unostentatious but given expression day after day in the lives of others, may be all many of us on this earth can ever find for ourselves, no matter how long we happen to live.

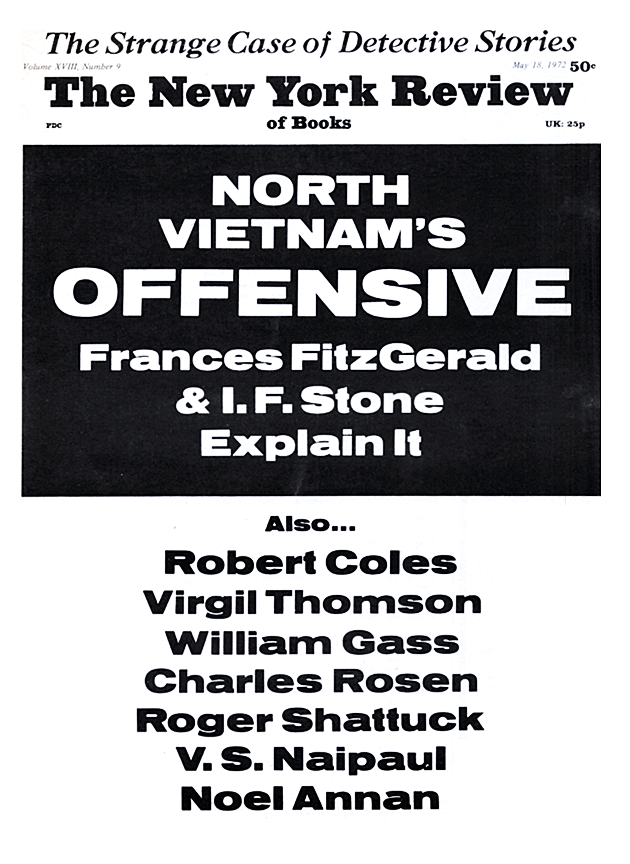

This Issue

May 18, 1972