Questions that have more to do with American culture than with American politics keep intruding themselves into the campaign, to McGovern’s embarrassment. McGovern prefers to discuss the “real,” political issues. Thus Eagleton was dropped lest his medical career distract the public from the “real” issues—Nixon’s record, the war, the economy. Eagleton’s ingenious but rather belated suggestion that his candidacy might serve to educate the public about “mental illness” was greeted without enthusiasm by McGovern and his advisers. (This issue, incidentally, illustrates the depth of the cultural divisions among us. Many Americans still resist the progressive view that neurosis should be regarded as a disease and not as a defect of character. Yet this “advanced” position has itself been under attack for years, and many intellectuals now regard the medical model of neurosis as naïve and outmoded.)

Since “cultural” issues seem to be working to McGovern’s disadvantage, it is easy to understand his desire to avoid them. Nevertheless those issues persist. In several states, for instance, busing continues to excite deep feelings. From McGovern’s point of view busing is another unreal issue. He seems never to have been able to understand or to identify himself imaginatively with the distress of working-class communities threatened with forced integration.

Working-class audiences may admire the courage and integrity of his defense of unpopular rulings of the Supreme Court, so striking in contrast to Nixon’s flouting of these rulings, but they are unlikely to take much comfort from McGovern’s assurance that he understands why parents are reluctant to send their children long distances to school by bus. Riding a bus to school is not what people fear. Rather, busing has become a symbol of the sacrifice of local needs and of whole neighborhoods to bureaucratic design—integration, urban renewal—imposed from above and supported, it appears, by wealthy suburbanites who themselves have nothing to lose from the implementation of these schemes. Rightly or wrongly, busing is identified with the disintegration of formerly close-knit ethnic neighborhoods, the collapse of schools that were once a source of local pride, the growth of crime, spiraling tax rates, and the collapse of the city itself.

Abortion poses a similar set of problems for McGovern. Here again working-class apprehensions conflict with the wishes of the liberals who make up the heart of the McGovern movement and who support legalized abortion either because they are feminists or because it coincides with the goal of “zero population growth.” McGovern cannot completely repudiate the demand for liberalized abortion laws without antagonizing many of his most devoted supporters, but neither can he endorse it: to do so would be fatal in working-class constituencies. Here too McGovern tries to escape from his dilemma by arguing that abortion is not a “real” issue—a disingenuous argument that has the additional disadvantage of being completely unconvincing.

There is only one way for a populist candidate to deal with these divisive cultural issues. Without denying their reality, he must attempt to unify his constituency around a set of radical economic demands. In the 1890s, the Southern populists attempted to eliminate the racial issue from Southern politics by presenting an economic program on which lower-class whites and blacks could unite in common opposition to the banks, the railroads, and the supply merchants. It has been clear from the beginning that McGovern’s principal hope of election is to follow a similar strategy and to hammer away at the issues of tax reform, income redistribution, the need to cut defense spending and to rearrange priorities. We have heard very little about these issues in recent months. In his speech to the New York Capital Society of Security Analysts in August, McGovern abandoned what was potentially his strongest issue, his plan for tax credits—the heart of his program of income redistribution. Although he still favors closing tax loopholes for the rich, for practical purposes this issue has also disappeared from his campaign.

Instead of following a populist strategy, McGovern has tried to get elected by running as a conventional liberal, whose differences with Nixon boil down to his opposition to the war and his concern for civil liberties. (These in themselves, it should go without saying, remain compelling reasons to support him. Nixon’s complete contempt for the First Amendment is no small matter.) Since McGovern is in fact a liberal and has been a liberal all along, even when seeming to present himself as a populist, it is not altogether surprising that he has chosen this course—the course of reassurance, mending fences, soothing ruffled feelings within the party. Perhaps the only thing that has been genuinely surprising about McGovern’s campaign is his groveling to Johnson, which appears to compromise even his opposition to the war and from which he had nothing to gain in any case—an act unforgivable politically, revolting morally. Even this ceremonial and futile visit to Big Daddy, however, suggests McGovern’s thoroughly conventional instinct for party unity and consensus.

Advertisement

The trouble is that having won the nomination as some sort of populist, appealing to a variety of discontents and to a pervasive feeling that something is radically wrong with American society, McGovern could not retreat from his earlier positions without losing his overriding asset in a campaign against Richard Nixon, his credibility. In spite of the Watergate affair, the grain deals, his failure to end the war, and his generally unsavory past, it is Nixon who presents himself as a man of candor and honesty, while McGovern is asked again and again to clarify his positions and to explain why he keeps changing his mind. The Democrats’ inability to turn Republican scandals to their own advantage may testify to a pervasive cynicism that takes it for granted that public life is always corrupt; but this cynicism might abate if the voters could be convinced that there is an important difference between the two parties. McGovern’s vascillation, however, has made him appear indistinguishable from other politicians.

The kinds of discontent around which McGovern organized his primary campaign may be too diffuse to be unified into a winning coalition; but he had really no other choice than to try. In spite of certain limitations inherent in populism itself (notably its inability to deal with cultural issues), I am not convinced that failure was by any means the inevitable conclusion of such a campaign.

Indeed what is astonishing about the campaign at this point is that McGovern’s position remains as strong as it is, in spite of his many blunders, evasions, and retreats. Although it is no longer likely that he will win, his position is much better, I believe; than the polls would indicate. Large numbers of people have not yet made up their minds, while others are no longer sure what McGovern stands for but intend to vote for him anyway in preference to Nixon. If McGovern had stuck to his original program, there is every reason to think Nixon would now be waging a desperately defensive campaign.

It is said that McGovern had to retreat in order to get the kind of money needed for a presidential campaign. Even with limited funds, however, he could have fought a somewhat limited campaign concentrating on a few crucial states. As a matter of fact this is exactly what he has had to do anyway, since his compromises did not convince the big spenders after all. They remain resolutely unreconciled to McGovern. Yet in spite of their hostility, he has managed to keep himself prominently in view and to get his message across. It is the content of the message, or lack of it, that inhibits his candidacy, not his inability to get the public ear.

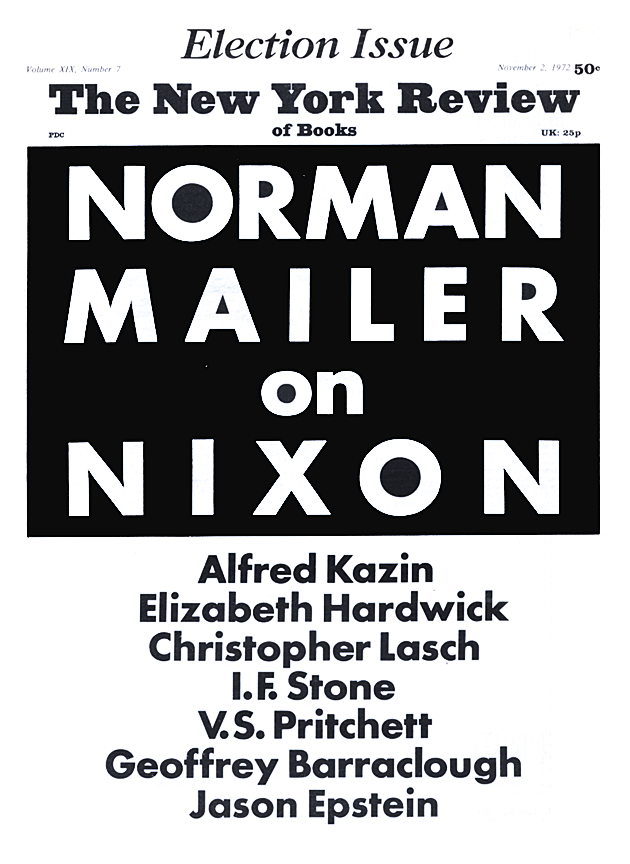

This Issue

November 2, 1972