I am writing this in Paris, in a room about 4′ by 10′, sitting on a wicker chair at a typing table in front of a window which looks onto a garden; at my back is a cot and a night table; on the floor and under the table are manuscripts, notebooks, and two or three paperback books. That I have been living and working for more than a year in such small bare quarters, though not at the beginning planned or thought out, undoubtedly answers to some need to strip down while finding a new space inside my head. Here where I have no books, where I spend too many hours writing to have time to talk to anyone, I am trying to make a new start with as little capital as possible to fall back on.

In this Paris in which I live now, which has as little to do with the Paris of today as the Paris of today has to do with the great Paris, capital of the nineteenth century and seedbed of art and ideas until the late 1960s, America is the closest of all the faraway places. Even during periods when I don’t go out at all—and in the last months there have been many blessed days and nights when I have no desire to leave the typewriter except to sleep—each morning someone brings me the Paris Herald-Tribune with its monstrous collage of “news” of America, encapsulated, distorted, stranger than ever from this distance: the B-52s raining mega-ecodeath on Vietnam, the repulsive martyrdom of Thomas Eagleton, the paranoia of Bobby Fischer, the irresistible ascension of Woody Allen, excerpts from the diary of Arthur Bremer—and, last week, the death of Paul Goodman.

I find that I can’t write just his first name. Of course, we called each other “Paul” and “Susan” whenever we met, but both in my head and in conversation with other people he was never “Paul” or ever “Goodman” but always “Paul Goodman”—the whole name, with all the ambiguity of feeling and familiarity which that usage implies.

The grief I feel at Paul Goodman’s death is sharper because we were not friends, though we coinhabited several of the same worlds. We first met twenty years ago. I was nineteen, a graduate student at Harvard, dreaming of living in New York, and on a weekend trip to the city someone I knew at the time who was a friend of his brought me to the loft on Twenty-third Street where Paul Goodman and his wife were celebrating his fortieth birthday. He was drunk, he boasted raucously to everyone about his sexual exploits, he talked to me just long enough to be mildly rude. The second time we met was four years later at a party on Riverside Drive, where he seemed more subdued but just as cold and self-absorbed.

In 1959 I moved to New York, and from then on through the late 1960s we met often, though always in public—at parties given by mutual friends, at panel discussions and Vietnam teachins, on marches, in demonstrations. I usually made a shy effort to talk to him each time we met, hoping to be able to tell him, directly or indirectly, how much his books mattered to me and how much I had learned from him. Each time he rebuffed me and I retreated. I was told by mutual friends that he didn’t really like women as people—though he made an exception for a few particular women, of course. I resisted that hypothesis as long as I could (it seemed to me cheap), then finally gave in. After all, I had sensed just that in his writings: for instance, the major defect of Growing Up Absurd, which purports to treat the problems of American youth, is that it talks about youth as if it consists only of adolescent boys and young men. My attitude when we met ceased being open.

Last year another mutual friend, Ivan Illich, invited me to Cuernavaca at the same time that Paul Goodman was there giving a seminar, and I told Ivan that I preferred to come after Paul Goodman had left. Ivan knew, through many conversations, how much I admired. Paul Goodman’s work. But the intense pleasure I felt each time at the thought that he was alive and well and writing in the United States of America made an ordeal out of every situation in which I actually found myself in the same room with him and sensed my inability to make the slightest contact with him.

In that quite technical sense, then, not only were Paul Goodman and I not friends, but I disliked him—the reason being, as I often explained plaintively during his lifetime, that I felt he didn’t like me. How pathetic and merely formal that dislike was I always knew. It is not Paul Goodman’s death that has suddenly brought this home to me.

Advertisement

He had been a hero of mine for so long that I was not in the least surprised when he became famous, and always a little surprised that people seemed to take him for granted. The first book of his I ever read—I was sixteen—was a collection of stories called The Break-up of Our Camp, published by New Directions. Within a year I had read everything he’d written, and from then on started keeping up. There is no living American writer for whom I have felt the same simple curiosity to read as quickly as possible anything he wrote, on any subject. That I mostly agreed with what he thought was not the main reason; there are other writers I agree with to whom I am not so loyal. It was that voice of his that seduced me—that direct, cranky, egotistical, generous American voice.

Many writers in English insist on saturating their writing with an idio-syncratic voice. If Norman Mailer is the most brilliant writer of his generation, it is surely by reason of the authority and eccentricity of his voice; and yet I for one have always found that voice too baroque, somehow fabricated. I admire Mailer as a writer, but I don’t really believe in his voice. Paul Goodman’s voice is the real thing. There has not been such a convincing, genuine, singular voice in our language since D.H. Lawrence. Paul Goodman’s voice touched everything he wrote about with intensity, interest, and his own terribly appealing sureness and awkwardness. What he wrote was a nervy mixture of syntactical stiffness and verbal felicity; he was capable of writing sentences of a wonderful purity of style and vivacity of language, and also capable of writing so sloppily and clumsily that one imagined he must be doing it on purpose. But it never mattered. It was his voice, that is to say, his intelligence and the poetry of his intelligence incarnated, which kept me a loyal and passionate addict. Though he was not often graceful as a writer, his writing and his mind were touched with grace.

There is a terrible, mean American resentment toward someone who tries to do a lot of things. The fact that Paul Goodman wrote poetry and plays and novels as well as social criticism, that he wrote books on intellectual specialties guarded by academic and professional dragons, such as city planning, education, literary criticism, psychiatry, was held against him. His being an academic freeloader and an outlaw psychiatrist, while also being so smart about universities and human nature, outraged many people. That ingratitude is and always was astonishing to me. I know that Paul Goodman often complained of it. Perhaps the most poignant expression was in the journal he kept between 1955 and 1960, published as Five Years, in which he laments the fact that he is not famous, not recognized and rewarded for what he is.

That journal was written at the end of his long obscurity, for with the publication of Growing Up Absurd in 1960 he did become famous, and from then on his books had a wide circulation and, one imagines, were even widely read—if the extent to which Paul Goodman’s ideas were repeated (without his being given any credit) is any proof of being widely read. From 1960 on, he started making money through being taken more seriously—and he was listened to by the young. All that seems to have pleased him, though he still complained that he was not famous enough, not read enough, not appreciated enough.

Far from being an egomaniac who could never get enough, Paul Goodman was quite right in thinking that he never had the attention he deserved. That comes out clearly enough in the obituaries I have read since his death in the half-dozen American newspapers and magazines that I get here in Paris. In these obituaries he is no more than that maverick interesting writer who spread himself too thin, who published Growing Up Absurd, who influenced the rebellious American youth of the 1960s, who was indiscreet about his sexual life. Ned Rorem’s touching obituary, the only one I have read that gives any sense of Paul Goodman’s importance, appeared in the Village Voice, a paper read by a large part of Paul Goodman’s constituency, only on page 17. As the assessments come in now that he is dead, he is being treated as a marginal figure.

I would hardly have wished for Paul Goodman the kind of media stardom awarded to McLuhan or even Marcuse—which has little to do with actual influence or even tells one anything about how much a writer is being read. What I am complaining about is that Paul Goodman was often taken for granted even by his admirers. It has never been clear to most people, I think, what an extraordinary figure he was. He could do almost anything, and tried to do almost everything a writer can do. Though his fiction became increasingly didactic and unpoetic, he continued to grow as a poet of considerable and entirely unfashionable sensibility; one day people will discover what good poetry he wrote. Most of what he said in his essays about people, cities, and the feel of life is true. His so-called amateurism is identical with his genius: that amateurism enabled him to bring to the questions of schooling, psychiatry, and citizenship an extraordinary, curmudgeonly accuracy of insight and freedom to envisage practical change.

Advertisement

It is difficult to name all the ways in which I feel indebted to him. For twenty years he has been to me quite simply the most important American writer. He was our Sartre, our Cocteau. He did not have the first-class theoretical intelligence of Sartre; he never touched the mad, opaque source of genuine fantasy that Cocteau had at his disposal in practicing so many arts. But he had gifts that neither Sartre nor Cocteau ever had: a genuine feeling for what human life is about, a fastidiousness and breadth of moral passion. His voice on the printed page is real to me as the voices of few writers have ever been—familiar, endearing, exasperating. I suspect there was a nobler human being in his books than in his life, something that happens often in “literature.” (Sometimes it is the other way around, and the person in real life is nobler than the person in the books. Sometimes, as in the case of Sade, there is hardly any relationship between the person in the books and the person in real life.)

I always got energy from reading Paul Goodman. He was one of that small company of writers, living and dead, who established for me the value of being a writer and from whose work I drew the standards by which I measured my own. There have been some living European writers in that diverse and very personal pantheon, but no living American writer apart from him.

Everything he did on paper pleased me. I liked it when he was pig-headed, awkward, wistful, even wrong. His egotism touched me rather than put me off (as Mailer’s often does when I read him). I admired his diligence, his willingness to serve. I admired his courage, which showed itself in so many ways—one of the most admirable being his honesty about his homo-sexuality in Five Years, for which he was much criticized by his straight friends in the New York intellectual world; that was six years ago, before the advent of Gay Liberation made coming out of the closet chic. I liked it when he talked about himself and when he mingled his own sad sexual desires with his desire for the polity. Like André Breton, to whom he could be compared in many ways, Paul Goodman was a connoisseur of freedom, joy, pleasure. I learned a lot about those three things from reading him.

This morning, starting to write this, I reached under the table by the window to get some paper for the typewriter and saw that one of the two or three paperback books buried under the manuscripts is New Reformation. Although I am trying to live for a year without books, a few manage to creep in somehow. It seems fitting that even here, in this tiny room where books are forbidden, where I try better to hear my own voice and discover what I really think and really feel, there is still at least one book by Paul Goodman around, for there has not been an apartment in which I have lived for the last twenty-two years that has not contained most of his books.

With or without his books, I shall go on being marked by him. I shall go on grieving that he is no longer alive to talk in new books, and that now we all have to go on in our fumbling attempts to help each other and to say what is true and to release what poetry we have and to respect each other’s madness and right to be wrong and to cultivate our sense of citizenliness without Paul’s hectoring, without Paul’s patient meandering explanations of everything, without the grace of Paul’s example.

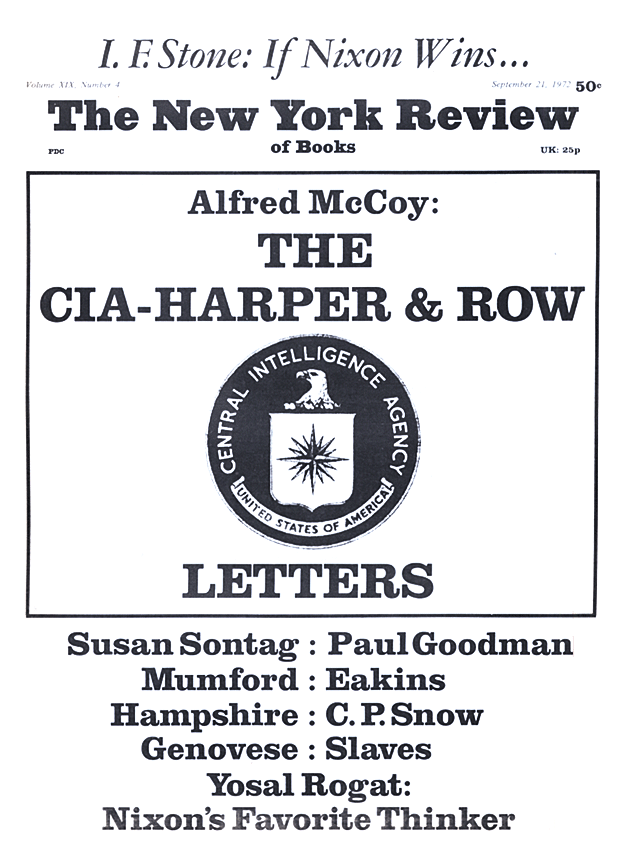

This Issue

September 21, 1972