One of the few welcome by-products of the Colonels’ regime has been to stimulate a flood of books on the recent history of Greece. Almost fifty titles have been published, ranging in seriousness from Pavlos Bakojannis’s sociopolitical study Militärherrschaft in Griechenland (Kohlhammer, 1972) to Melina Mercouri’s I Was Born Greek (Doubleday, 1971). Most of these are anti-Colonel, some are unashamedly pro. But another, much smaller, but in many respects more interesting group seems to take the position that, while military dictatorship is generally undesirable, nonetheless the Greeks are such an unregenerate and incorrigible rabble that the rigors of martial law are the only means of keeping them in line. The most sophisticated proponent of this view is David Holden, the author of Greece Without Columns (whose subtitle is The Making of the Modern Greeks, a little presumptuous, perhaps, on the part of a writer who appears to know little or no Greek).

Holden’s avowed aim is to sweep away the myths that surround the modern history of Greece and the Greeks, and that color our understanding of the present situation. This is an entirely laudable aim, and I would be the first to agree with him that more cant has probably been written about Greece than about any other country in Europe. But in his eagerness to sweep away existing myths he propagates new ones. This is not to argue that he does not have some useful things to say. He is quite right, for instance, in seeing the Colonels as the lineal descendants of General Metaxas, who, under the aegis of King George II, ruled Greece as a quasi-fascist dictator between 1936 and 1941. Papadopoulos, like the general, is bent on eliminating the “worm of egocentricity,” and, like his predecessor, he seems bound to fail. Holden also effectively demolishes the more patently absurd elements in the fashionable mythology of “CIA involvement” in the Colonels’ take-over.

Moreover, he has a clear gift for racy expression, although his obvious delight in polemic frequently gets the better of him. “Like the illegitimate child of some hedgerow affair, modern Greece was born out of, and into, the politics of irresponsibility.” Is this really the language of reasoned explanation and inquiry in which Holden believes himself to be engaged? He can, too, indulge in humbug worthy of that archhumbug Kazantzakis, for whom he clearly has great admiration. The Greeks, he tells us, “live in a state of total and permanent contradiction of each other and themselves.” What on earth does this mean?

To succeed, such an exercise in demythologizing requires scrupulous attention to the facts of Greece’s historical experience. Too often Holden weakens the force of his argument through hyperbole or downright inaccuracy. Nonetheless, Holden’s view of recent Greek political history seems to be gaining some credence. Before these new myths gain acceptance it seems to me important to study them in some detail.

Greece Without Columns contains a number of irritating historical errors. The Phanariots did not exist in Byzantine times. Adamantios Korais, the intellectual mentor of Greek independence, was not a schoolmaster. Nor did he invent the katharevousa (or artificial purified Greek). Nor did he go back to Greece during the War of Independence to show the Greeks how to run their affairs. If Holden is going to write off so important a figure as Korais as an “evil genius” (following Sir Steven Runciman), then he really should get his facts straight. The monks of Lavra did not begin the War of Independence. The Greek Communist Party (KKE) of the Interior is not of “maoist” tendency: an error reminiscent of Churchill’s dismissal of the insurgent Greek communists in December, 1944, as “Trotskyists.” And it was with the interior faction that Theodorakis was associated until his recent defection from the party, not the third, or “Chaos” group.

These and other errors are relatively minor. What raises more serious questions are the facts that Holden adduces in support of his thesis that Greek politics are “the politics of irresponsibility” in which “petty factionalism” is the norm; that Greece before the coup was in a condition of “bourgeois anarchy” and that because of “unbridled patronage” the welfare of the state was forgotten in a “welter of personal ambition”; that practically every statesman in independent Greece has fallen victim to “overweening pride” (Kharilaos Trikoupis? Panayiotis Kanellopoulos?); that parliamentary democracy in Greece was utterly incapable of reforming itself from within; that dictatorship, and more particularly military dictatorship, is quite as much the norm in Greece as “ostensible” democracy. The Colonels, he argues, may not be very agreeable, or may even be ludicrous, but what is now going on in Greece, or something very like it, has often happened before, so what is all the fuss about? Why don’t we simply allow the Greeks to go on festering in their mean and irresponsible way?

Advertisement

Holden tells us that ten “major” coups d’état have taken place in Greece during this century, but does not explain what he understands to be a major, as opposed to a minor, coup. Does he mean by major one that results in the overthrow of an existing government? If so, it would be interesting to know which specific coups he is thinking of, since the last successful military coup before that of the Colonels took place in 1926. What Holden does not tell us is that, with the exception of the coup of Pangalos in 1925, in every case since 1900 the military soon stepped down voluntarily in favor of civilian governments and elections.

Before the Colonels appeared on the scene, the Greek military for the most part acted on behalf of existing political organizations rather than seeking direct political power for themselves. After more than six years the Colonels, despite their earlier promises of a return to democracy, have shown no eagerness to relinquish power.

The military dictatorship is not, as Holden would have us believe, a recurrent feature of the Greek political scene. Pangalos’s opéra bouffe dictatorship lasted barely a year, while the Colonels have already well outlasted Metaxas’s dictatorship, which was not strictly a military dictatorship and was not brought into being by a military coup. No one would dispute that the Greek army has a sorry political record in the twentieth century; but why needlessly exaggerate the picture?

Again, we are told that constitutions sprout from the agile minds of the Greeks like “leaves from a vigorous tree,” a favorite simile (in the 1920s administrations “swirled in and out of office like leaves in a high wind”). It is a striking “fact,” Holden assures us, that virtually every Greek regime, “whether ostensibly democratic or dictatorial,” has taken “enormous pains to equip itself with a formal constitution.” The unsuspecting reader might think that there have been well over 100 constitutions in force since independence. In fact there have been six (1844, 1864, 1911, 1927, 1952, and 1968), all save the last adopted after reasonably free debate in a popularly based assembly. Moreover, the 1952 constitution is essentially a revision of that of 1911, which in turn is a revision of that of 1864.

We learn that after the constitutional crisis of July, 1965, George Papandreou’s Centre Union (EK) fell apart. In fact, only 45 out of 171 deputies defected to Stefanopoulos and the “apostates.” This still left the Centre Union, with 126 out of 300, as easily the largest single party, followed by the National Radical Union (ERE) in coalition with the Progressive Party, with 105, and the United Democratic Left (EDA) with 22. And precisely which of Panayiotis Kanellopoulos’s actions in the months before April, 1967, “suggested that his desperation had taken his judgment prisoner”? Holden fails to appreciate that much of the seeming agitation in Greek politics before the Colonels’ coup was so much froth on the surface—part of the “game of politics” as played in Greece. Between the crisis of July, 1965, and that of April, 1967, there was one political killing in Greece. In Northern Ireland during 1972 there were 467 killings.

This kind of blanket condemnation of the old politikos kosmos has of course constituted a major plank in the Colonels’ propaganda effort, particularly after they abandoned their initial pretense of having intervened in order to forestall an imminent communist take-over. Holden can scarcely be described as an apologist for the Colonels; but in his anxiety to correct what he considers to be a distorted picture of the regime he can be badly mistaken. The “inescapable suspicion of perjury and propaganda” surrounding so many of the torture allegations made against the Colonels, he maintains, casts doubt on the findings of the European Commission of Human Rights of the Council of Europe that torture was, during the period of their investigation, an administrative practice of the regime.

This is indeed a grave charge. But let us take a closer look at what he considers to be the most notorious of these “exaggerated, if not fabricated” allegations. This, he tells us, occurred in Strasbourg in 1968

…when the Greek Government produced two prisoners to testify to the Human Rights Commission that they had not been tortured. Before they could do so, the two men disappeared, to surface in Norway a few days later…. There they announced that, on the contrary, they had been tortured; but after a few more days they reappeared yet again in Greek Government hands to maintain that they had been kidnapped by Papandreou’s men, including twenty “communists” with guns, and had made their previous statements under duress…. From such a scene of black comedy it was impossible for any detached observer to draw anything much save, perhaps, a renewed determination to hold hard to his natural skepticism in dealing with Greek affairs.

True, but for the fact that Holden’s account is seriously inaccurate.

Advertisement

The “detached observer” of what actually took place may perhaps draw altogether different conclusions. Constantine Meletis and Pandelis Marketakis were indeed brought to Strasbourg to testify on behalf of the regime that they had not been ill-treated while in custody. They then defected and proceeded to testify under oath before the European Commission of Human Rights that they had in fact been tortured. Only then did they decamp for Norway. Shortly afterward one of them (Marketakis) redefected to the Greek government. He then proceeded to claim, and as the Commission drily noted, not under oath, that he had been manhandled by Jens Evensen, the Norwegian government’s legal agent, and that his sworn testimony before the Commission had been given under duress. He further offered to return to Strasbourg to repudiate his earlier testimony. But in fact he failed to appear again before the Commission, apparently on the grounds that a visit to Strasbourg would be “extremely perilous.”

The Commission concluded not unreasonably that Marketakis, who had earlier claimed that the regime had threatened reprisals against his family which was still in Greece, could not be regarded as a free and independent witness. Meletis continues to live in exile and has not withdrawn his testimony. The facts of the Meletis/Marketakis case are contained in the Commission’s heavily documented four-volume report, itself a unique document of contemporary history. Whatever else this bizarre episode does, it does not shake confidence in the findings of the Human Rights Commission.

Dismissing George Papandreou as being more interested in power than in reform, Holden maintains that the Colonels, in contrast, have a firm commitment to political and social revolution, that they have a “populist” appeal to the peasants and lower middle class, that, in short, they are ardent levelers. Holden lays great stress on Papadopoulos’s humble background as the son of the village schoolmaster of Elaiokhorion, near Patras. But it is difficult to see what this is supposed to prove. George Papandreou was the son of the equally humble priest of the neighboring village of Kalantzi, while Karamanlis came from a village in Macedonia. Holden finds a special significance in the fact that most of the Colonels were born and bred in the provinces. But so, too, were most former politicians. That the Colonels are bent on crushing the power of the old political establishment is beyond dispute, and there certainly is a “populist” flavor to their rhetoric. But what about their practice? Surely “populism” must imply redistribution of the national income in favor of the poor and an attempt to curb the power and privilege of big business.

In fact, the available evidence (of which Holden gives scarcely a hint) indicates that the relative income of the peasants and urban workers (relative, that is, to property and capital owners) has been declining over the past six years. The proportion of government expenditure allotted to education, health, and social services has declined under the Colonels, while that to defense and security has markedly increased. For a regime to lower the age for compulsory schooling from fifteen to twelve (reversing a major plank of Papandreou’s 1964 educational reform) and to emasculate peasant cooperatives and trade unions in the way this one has done shows a rather odd form of populism. The Greek workers and peasants, at least, are able to see things for what they are. During the crisis years of 1965-1966, 78,000 people emigrated. The figure for 1969-1970 is 173,000.

The contracts that the Colonels awarded with great fanfare to Litton-Benelux, Onassis, and the Macdonald Company (all three have since foundered) are scarcely the work of anti-establishment radicals. Moreover, Papadopoulos has shown increasing signs of desperation in his efforts to grovel before the country’s economic oligarchy. In a speech before the Association of Greek Shipowners, of which he has been elected president for life, he ingratiated himself by offering to allow the sons of shipowners to complete their national service in three months (Nea Politeia, March 4, 1972). The sons of peasants are required to serve for two years.

Holden is very sparing with information that would provide the background against which we could objectively judge his dismal picture of a political system entirely given over to feckless and unregenerate politicians shamelessly manipulating a system that was beyond any hope of reform. In the process he plays down the fact that Greek politics had stabilized remarkably during the 1950s and early 1960s. In the elections of March, 1950, no fewer than forty-six parties entered the elections, among them the Greek Motorists Party (Komma Aftokinitiston Ellados) and the National Byzantine Party of Greece (Ethnikon Vyzantinon Komma Ellados), led by the pretender to the throne of Byzantium. By the time of the last elections held before the coup (February, 1964), the number of parties had dropped to four, of which two (the National Radical Union and Spyros Markezinis’s miniscule Progressive Party) were in coalition. Holden tells us that on the average the government changed almost every year since the turn of the century. But surely it is of equal significance that between 1950 and 1967 there were only six governments, apart from service governments and two that failed to receive a vote of confidence. Between 1955 and 1965 there were three.

Karamanlis held office as prime minister for eight consecutive years, a term of office not easily matched in recent British politics. But this Holden regards as essentially a freakish interlude, to be explained largely by the increased opportunities for patronage open to Karamanlis as a result of American aid. Beneath the surface, in Holden’s view, Greek politics continued in their neocolonial decadence.

Of the 123 years between 1844, when independent Greece acquired its first constitution, and 1967, 111 have been years of parliamentary rule. For only twelve years during this period were parliamentary institutions in abeyance, and this includes the wartime occupation and its immediate aftermath. Parliamentary government in Greece may have been imperfect, at times seriously so, but it is surely to the credit of the Greeks that they managed to preserve a reasonable likeness of parliamentary democracy when other countries (as Holden himself points out) with similar historic, economic, and social weaknesses have succumbed to authoritarianism.

Holden’s criteria of acceptable democracy seem high indeed—witness his sneer at the “more or less democratic” countries of the Council of Europe. Although there is no evidence so far that the Colonels can be regarded in any real sense as reformists, Holden believes it to be arguable that radical social change in Greece can be brought about only by authoritarian measures.

This quite unnecessarily gloomy prognostication is at least partly the result of his inadequate appreciation of the realities of Greece’s past history and of the situation in Greece in 1967. He talks of Greece under George Papandreou as being caught in a spiral of inflation, whereas in fact the average annual rate of inflation between 1963 and 1966 amounted to a mere 3 percent (in Britain during 1971 it was three times as high). Moreover, he believes Greece to have been in the midst of a genuine economic crisis when the Colonels took over. In fact the GNP rose at an annual rate of 7.65 percent during 1963-1966, a rate higher than that achieved by any other country in Europe. That Greece was able to maintain her remarkable momentum of growth during the political, but not economic, crisis of 1965-1967 is perhaps an indication that her institutions were not quite in the state of administrative confusion that he would have us believe.

In fact, on almost every count, economic chaos, political violence, near civil war, etc., if Greece was ripe for dictatorship in 1967, then how much more so is Britain in 1973? This is precisely what the Colonels themselves would argue. Western parliamentary democracy they hold to be in a state of irreversible decline. Sooner or later, they believe, the Western world will turn to the “Greek model” as their only hope of salvation from the prevailing “socialist misfortune” and “Marxist” democracy of the West. In the words of one of their handouts, the “New Democracy” (a term earlier employed by Rafael Leonidas Trujillo) purports to guarantee freedom of expression without “extraneous irritants like strikes and demonstrations.”

The coup of 1967 occurred, despite the seeming chaos of the preceding two years, at one of the most hopeful junctures in Greece’s recent political history. There seemed a real possibility that Greece, without resorting to authoritarian methods, would be able to develop modern and responsive political structures, enabling her to emancipate herself from her heritage of political weakness and economic backwardness. With a dynamic economy which was clearly reaching the stage of “take-off,” Greece seemed ready to rejoin Europe. The Colonels’ coup, however, has set Greece’s political development back by at least a generation and has reopened old wounds which had gradually begun to heal in the stability and growing affluence of the 1950s and early 1960s.

The longer the Colonels stay in power the more Greek society will be polarized. The recent abolition of the monarchy in the wake of an attempted naval counter-coup and proclamation of a “presidential republic” clearly indicate that they have no intention of voluntarily abdicating their power or of submitting themselves to a fair test of popular support. For the ostensible purpose of the referendum to be held on July 29 is not only to ratify the creation of a republic but also to elect Papadopoulos, the sole candidate, to a seven-year term as president of the republic. Undoubtedly the results will go in the Colonels’ favor. Already they have banned public discussion during the period before the vote, while martial law will remain in force in Athens and Piraeus, the main urban centers. In any case a government spokesman has emphasized the “heads we win, tails you lose” quality of the referendum. A “no” vote will not be considered as a vote for the monarchy or, indeed, as a vote against Papadopoulos as president. This kind of blatant chicanery does not hold out much prospect that the elections which Papadopoulos has promised by the end of 1974 will be remotely acceptable as an indicator of public support.

There certainly is a great need for demythologizing, if not debunking, the history of Greece, and Holden’s book is to be welcomed as providing an alternative view of the course of modern Greek history and the nature of Greek society. But what a pity he has dissipated his opportunities by indulging in the very rhetoric, hyperbole, imprecise generalization, and tendency to gloss over unpalatable facts that he deplores among the Greeks.

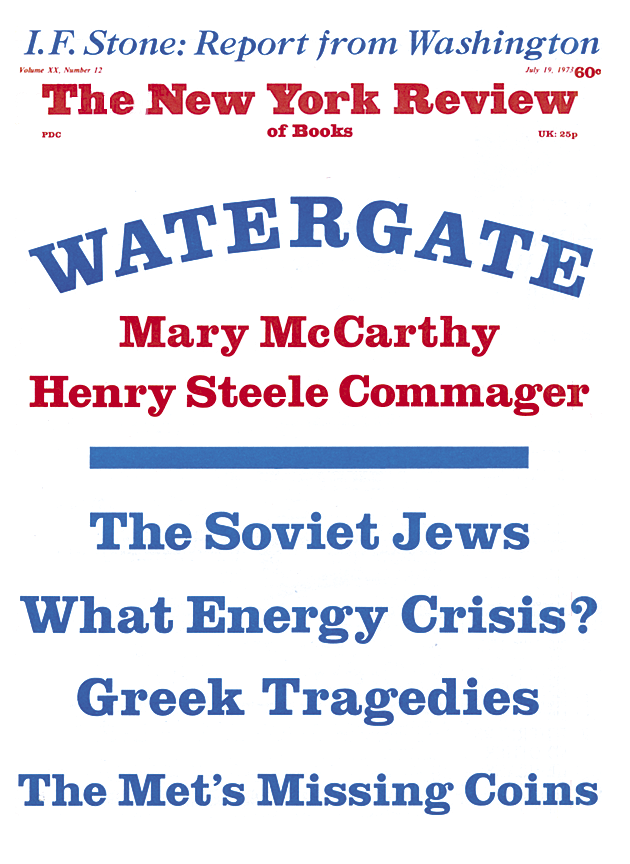

This Issue

July 19, 1973