Nobody has done more to arouse an interest in Spanish literature among English-speaking readers than Mr. Brenan. His scholarship is impeccable and his prose style felicitous.

Spain in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was a very strange country and I am very glad I didn’t have to live in it. First, there was the Jewish Problem. When the rule of Islam was over, a good many Jews, whether out of conviction or for worldly reasons, were baptized and became known as the New Christians. By the middle of the fifteenth century they had become the Spanish middle class.

They controlled the silk and cloth industry, they collected the royal and ecclesiastical revenues and many of the best offices in the church, notably the canonries, were filled by them. The judges, lawyers, doctors and apothecaries came mostly from their ranks and a contemporary account gives them as numbering one third of the population in the larger cities.

(The only disability they seem to have suffered under was that they were forbidden to bear arms.) Consequently, they were more hated by the masses than those who had kept their Jewish faith.

Recent research has uncovered an interesting story. St. Teresa’s grandfather, Juan Sánchez de Cepeda, a prosperous merchant, suddenly announced his conversion to Judaism and apostatized along with his wife and children. Soon after, a tribunal of the Inquisition was set up in Toledo. Faced with the alternative of returning to the Church or being burned at the stake, he not unnaturally chose the former. Why did he renounce Christianity in the first place? Mr. Brenan suggests that, at the time, it was physically safer to be a Jew than a New Christian. In several cities there had been riots in which the merchant quarter had been sacked, while the Jewish quarter was left untouched. It is also probable, though not proven, that St. John of the Cross was partly Jewish. His uncles had been in the silk trade.

Secondly, there were in Spain in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the extraordinarily complicated goings-on in the Carmelite order, and it is with these that Mr. Brenan’s book is mostly concerned. The first positive information about them comes from a Greek monk called Phocas, who visited Mount Carmel in 1185 and found a community of anchorites living there in seclusion and great austerity. In 1258, when the Saracens were closing in, most of them emigrated, a great many to England.

The Carmelites expanded rapidly in Spain, but began to find their rule too austere, and in 1432 Pope Eugenius gave them a milder one which was general until, in 1562, St. Teresa founded a reformed branch, emphasizing poverty, fasting, and prayer. The laxer branch became known as Calced Carmelites, St. Teresa’s as Discalced. The history of the relations between them, the feuds, the intrigues would make a fascinating if very depressing movie. Much depended upon the attitude of the authorities in Italy. The Carmelite General Rubeo, who had first been in favor of the reform, turned against it. The papal nuncio Ormaneto backed it, but then he died and his successor, Sega, was strongly prejudiced against it and gave his support to Rubeo’s emissary, Tostado, who placed all Carmelite houses under the direction of the Calced.

In October, 1577, there was a terrible scene.

Teresa’s term as prioress had lapsed, her successor had come and gone and now a third choice had to be made. There were two parties among the nuns—the strict party who wanted Teresa back and the lax party who wanted someone else. Tostado sent down the provincial to superintend the affair with instructions to make sure that the Calced candidate was elected, and he, thinking he could best secure this by frightening the nuns, threatened to excommunicate any of them who should vote for Teresa. But in spite of this, fifty-five of them, encouraged by Fray Juan de la Cruz’s exhortations, declared their intention to vote for her, and they formed a majority…. The provincial took his stand by the grille, abusing and excommunicating those nuns who voted contrary to his wishes and striking, crumpling and burning their voting papers. But even this did not produce the effect that he wanted. He therefore gave orders that none of the recalcitrant nuns should attend mass or enter the chapel or see either their confessors or their parents until they had voted as he desired. When they once again refused to do this he declared the election null and void, excommunicated them a second time and appointed the nun who had obtained the lesser number of votes as prioress.

Fray Juan de la Cruz’s role in this was not forgotten, and in December he was arrested and cast into prison. Before describing his experiences there, I should say something about his early career.

Advertisement

He was born in 1542 and baptized under the name of Juan de Yepes y Alvarez. His father, Gonzalo de Yepes, orphaned at an early age, was brought up by his uncles who were in the silk trade, joined them and seemed all set for a prosperous career, but then he fell in love with a poor silk weaver, Catalina Alvarez, and married her. Outraged, his uncles cut him off. He became a silk weaver himself and died twelve years later, leaving his widow and three sons in great poverty. Juan seems to have inherited from him an indifference to worldly success: what the father was prepared to sacrifice for Eros, the son was prepared to sacrifice for Agape.

His mother could not support him and he was placed in an orphanage, where he was taught to read and write. Attempts were made to train him for some manual job, but he proved totally incompetent. He spent some time working in a hospital for incurable syphilitics—rather an odd occupation, surely, for a boy—but its administrator noticed his love of reading and got him enrolled in a grammar school run by Jesuits. For someone with his tastes and talents, the priesthood seemed the obvious profession, but he was already determined to forsake the world and, at the age of twenty-one, joined the Carmelite order and adopted the name Fray Juan de San Matías. He then went to study in the Carmelite college attached to the University of Salamanca.

The turning point in his career came in 1567 when he met St. Teresa. He had become discontented with the relaxed rule of the Calced Carmelites and was thinking of joining the Carthusians. St. Teresa persuaded him to remain and assist her in her reforms, and in November, 1568, he changed his name to Fray Juan de la Cruz.

Though he became her confessor and she said she never had a better one, relations between them were not always easy. She immediately recognized his saintliness, but his incapacity in practical affairs may have sometimes irritated her, and he may have sometimes thought her too concerned with the things of this world.

We hear of him mortifying her by handing her an unusually small host at communion when he knew that she liked large ones, giving his reason for this that she was too fond of gustos or spiritual consolations…and she once remarked: “If one tries to talk to Padre Fray Juan de la Cruz of God, he falls into a trance and you along with him.”

From his student days on, his reproaches of the conduct of others, however just, seem to have caused great offense. “Let us be off—that devil is coming,” his fellow students would say. Later in life, there were two men, Diego Evangelista and Fray Francisco Crisóstomo, both of whom he had reproved for leaving their priories too often to preach elsewhere, who became his mortal enemies and, when the opportunity arose, took vengeance.

In appearance, Juan de la Cruz was a very small man [under five feet] with dark hair and complexion, a face round rather than long and a slightly aquiline nose. His glance, we are told, was gentle. He grew a slight beard and went bald early…. Unlike Teresa, he was singularly devoid of all those vivid and arresting features that one calls personality. We see an inward looking, silent man with downcast eyes, hurrying off to hide himself in his cell and so absent-minded that he often did not take in what was said to him.

But now back to his experiences in prison. Physically this was sheer hell.

His bed was a board laid on the floor and covered with two old rugs so that, as the temperature of Toledo sinks to below freezing point in winter and a damp chill struck through the stone walls, he suffered greatly from the cold. Later when the summer came round he suffered equally in his stifling closet from the heat. Since he was given no change of clothes during the nine months that he was in prison, he was devoured by lice. His food consisted of scraps of bread and a few sardines—sometimes only half a sardine. These gave him dysentery.

Then he was frequently scourged, the marks of which he bore to the end of his life.

His tunic, which was clotted with blood from his scourgings, stuck to his back and putrified. Worms bred in it so that his whole body became intolerable to him.

But then something extraordinary happened. After some six months he was given a new jailer who took pity on him and gave him a new tunic. He also gave him a pen and ink so that he could “compose from time to time a few things profitable to devotion.” One evening St. John heard a young man singing a popular love song in the street outside.

Advertisement

I am dying of love, dearest. What shall I do? Die.

He fell into an ecstasy and started writing his most famous poem, “The Spiritual Canticle,” and composed several others.

In order to allow him some fresh air, his new jailer would leave the door of his cell open while the friars were taking their siesta. This gave him the opportunity to loosen the staples screwed into the door to hold the padlock, and on the fourteenth of August, 1578, he, miraculously, considering his enfeebled state, managed to escape.

His next ten years were peaceable and happy, living in various priories, acting as a confessor and also, no doubt, having mystical visions. Then, in 1588, when Nicolas Doria, a former Genoese banker who had joined the Carmelites ten years before, was elected vicar-general, he was soon again in trouble.

Inflexible, calculating, despotic, with great business capacity and drive, he [Doria] had his own ideas on how the Discalced should be governed and wished to be free to carry them out. In doing so he would show no respect for persons.

He set up a consulta, composed of six elected councilors, sitting in perpetual session, which would impose its authority on all priories and convents, irrespective of their special problems. To this St. John of the Cross was strongly opposed. He believed that no prior should be re-elected after his two-year term because he was convinced that power always corrupts, and he advocated election by secret ballot. His popularity with the nuns and his reputation for sanctity brought Doria to the conclusion that here was the enemy he must destroy. He sent Fray Diego Evangelista down to Andalusia to collect evidence of Juan’s scandalous conduct.

Diego would question them minutely for hours on end, and, if he could not get what he wanted by threats would misconstrue and falsify what they had said and then, without giving them what he had written to read through, order them to sign.

One nun was made to declare that Fray Juan had kissed her through the grille, but, as St. Teresa had previously observed:

If a friar questioned a not very intelligent nun for several hours on end he could make her say anything he wanted because nuns were easily frightened and accustomed to obeying their superiors.

San Juan refused to defend himself and by the beginning of 1591 was deprived of any office. In September he was taken ill with an inflammation of his right foot and went to the priory of Ubeda. Unfortunately its prior was his other old enemy, Fray Francisco Crisóstomo, who treated the dying man very harshly. On December 14 Juan died. What followed was, by modern standards, ghoulish. The crowd rushed into the priory. One of them bit off his toe, others took snippings from his hair or tore off his nails. His body reached Segovia minus an arm, a foot, and several fingers. Later the remaining limbs were cut off and, except for an arm given to Medina del Campo, and a finger or two bestowed elsewhere, were restored to Ubeda. Segovia kept only the head and trunk.

In 1675 he was beatified and canonized in 1720.

I find the man and his life as fascinating as Mr. Brenan does. I wish, though, I could share his enthusiasm for the poems, but I can’t. I can sense their musical felicities and appreciate the love of God’s creation which they exhibit. (In his prose works he could write: “All the beauty of the creatures, compared to the infinite beauty of God, is the height of deformity,” which smacks to me of Gnosticism. But in the poems, if there is any inclination toward heresy, it is toward Pantheism.) But I am forced to confess that the poems bore me. I should, however, very much like to read translations, if there are any, of a poet I had never heard of, Garcilaso, who introduced into Castilian poetry the Italian hendecasyllable and was, so Mr. Brenan tells us, the main poetic influence on St. John of the Cross, though Garcilaso’s subject matter was his enfeebled state, managed to escape.

I have no objection to “religious” poetry as such. For example, I love George Herbert’s poems, but they deal with experiences like guilt, contrition, prayer, Divine Providence, etc., of which I have some first-hand knowledge. But I do not believe it is possible to write a satisfactory poem about the mystical union. I think I understand why, when theologians like Gregorius, St. Bernard, and St. Peter Damian wanted to describe this experience, granted to very few people, to the average Catholic, they should have resorted to the erotic poetry of the Song of Songs. What they seem to be saying is that there are only two human experiences in which egoconsciousness is completely obliterated, the mystical union and the sexual orgasm. The difficulty about this is that the average reader is apt to take what they intended to be an analogy as an identity and to imagine the mystical union as being itself an erotic experience. Thus, when one looks at Bernini’s famous sculpture of St. Teresa in ecstasy, what one sees is a woman in orgasm. I’m perfectly certain that the two experiences must be totally different. Agape and Eros are not the same. No, I’m sorry, for me St. John of the Cross’s poems simply don’t work. Give me Gongora every time.

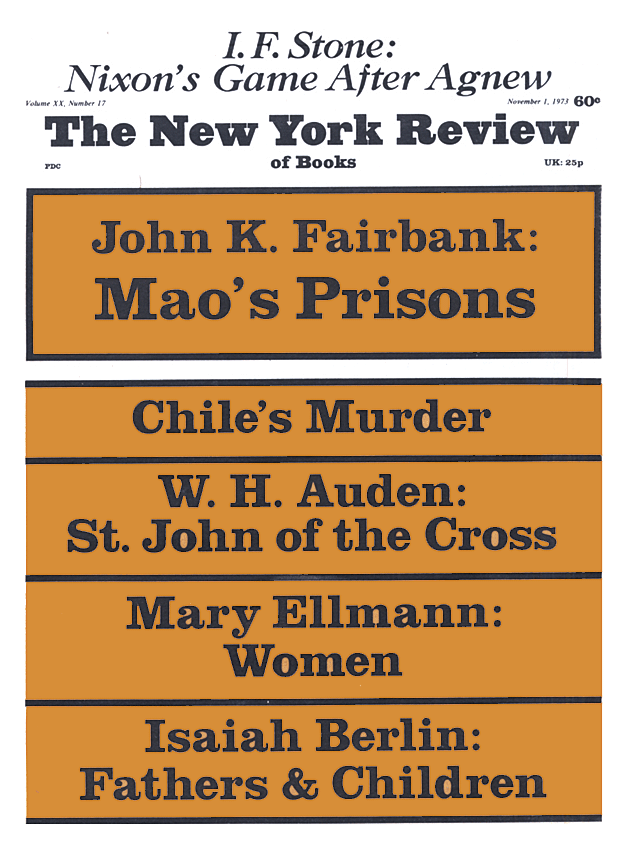

W.H. Auden wrote this review, including its title, and the accompanying poem this summer. He frequently contributed to this paper. We mourn his death.

—The editors

This Issue

November 1, 1973