Every author has his own special reason for writing about a trial. So the first question to come to mind is why Murray Kempton chose to spend almost seven months in Manhattan’s Criminal Courts Building, following the prosecution of thirteen Black Panthers. Obviously any account of a criminal case provides some insight into the functioning of justice. But even in the opening pages of The Briar Patch (a mistaken and misleading title) it becomes plain that Kempton has something much more ambitious in mind. His subject is the condition of American radicalism itself.

In the early morning hours of April 2, 1969, five-man squads of New York policemen, armed with shotguns and wearing bulletproof vests, pounded on a succession of apartment doors throughout the city. This foray, which ranged from Washington Heights to the East Village, resulted in the arrest of twelve black citizens, all of them members of the New York branch of the Black Panther party. Two others were already in custody on other charges, and seven more were rounded up later. Of these twenty-one young men and women, thirteen were eventually brought to trial on 156 counts involving attempted arson, attempted murder, and three kinds of conspiracy. They were charged with, among other things, planning to blow up various police stations, school buildings, a railroad yard, and the Bronx Botanical Gardens. At the end of the trial the jury found the defendants innocent of all these crimes.

Kempton leaves no doubt that this was entirely a New York event. The arrests, indictments, and prosecutions had no connection whatever with John Mitchell’s Justice Department, but originated within the city at the midpoint of John Lindsay’s administration. Yet in its major particulars, New York’s Panther case paralleled the attempts to convict war protestors in Gainesville, Harrisburg, Camden, and other American cities. Like the others, it was a conspiracy trial. People found themselves arrested for having participated in discussions which the authorities chose to construe as penultimate planning sessions. For example, it was suggested that at the time of their apprehension the Panthers were on the verge of planting explosives in Bloomingdale’s. In addition, nearly all the government’s evidence came from infiltrators who not only dissembled their way into the discussions, but revealed an uncommon enthusiasm for even the most hypothetical of projects. Finally, the police, prosecutors, and others connected with the case really believed that a local jury would vote to convict in spite of the tawdriness of the evidence.

Trials of this kind are not surprising when they come from an administration that gave custody of the nation’s justice to John Mitchell, Richard Kleindienst, and William Rehnquist. But how could such a case come about in New York Country—the statutory name for Manhattan—which boasts one of America’s most liberal and tolerant citizenries? Kempton’s book shows, better than anything else I have seen, how the criminal justice apparatus can pursue its course and remain virtually untouched by the outside, even in a borough that gave two-thirds of its votes to John Lindsay and almost that number to George McGovern.

Put simply, the proceeding was an exercise in deception, consciously conceived and cruelly executed. The police department under Howard Leary, through its Bureau of Special Services, operated much like that of a South American junta in its use of surveillance and infiltration. The district attorney, Frank Hogan, found no difficulty in believing that the accused formed a “paramilitary structure” ready to “harass and destroy” some of the city’s leading institutions. George McGrath, the commissioner of corrections, identified the defendants as “dangerous, obdurate, and untrustworthy prisoners” and hence confined them in separate jails so they could not confer (conspire?) on a common defense. The presiding judge, John Murtagh, especially chosen for the case by Frank Hogan, remarked even before the trial began, “They have enough on those people to hang them.” I only wish that Kempton had speculated on why, in view of the political and demographic changes in the city, such men and their methods continue to hold power. Nor does he remark on the common origins of the leading figures on the state’s side. I wonder whether certain perceptions and procedures are characteristic of a generation I might call the administrative Irish, a question perhaps better left to Wilfrid Sheed or Garry Wills.

For all this, the jurors, whom the prosecution initially had deemed satisfactory, voted to acquit. Kempton’s is basically a book about New York, and the jury members reflect still another part of the city. According to the process by which juries are selected only voters are called; conservative types tend to cop themselves out; and older people are usually challenged in the voir dire. Thus the panel that emerged for the Panther case, composed almost entirely of middle-class Manhattan liberals, was not atypical. It contained three editors, two teachers, several civil servants, and a Columbia graduate student, hardly the cross section that would make the verdict a vindication of democracy. Even so, the account shows how the jurors, as much by their own devices as from the prodding of defense counsel, asked sharp questions and gradually grew disgusted with the transparency of the prosecution’s case.1 But this was small consolation for the defendants, who remained in jail for more than a year prior to and during their trial.

Advertisement

The case was a disgrace to the city. While the behavior of the judge and the district attorney was probably beyond the control of the mayor’s office, the political zealotry of the police and the callousness of the department of corrections fell well within the mayor’s jurisdiction. In one sense at least the Panther case was John Lindsay’s Watergate: his imperviousness to the idiocy and insensitivity of subordinates.

The Briar Patch tries to show what it must be like to be black and radical in New York City. Whether a white writer can fathom the black mind is an issue that does not arise. For Kempton presents his subjects by rendering their outward behavior, in the best tradition of that method. He goes outside the courtroom to show how his subjects actually spent their lives: the houses they lived in, where they worked, where they traveled; what they discussed, thought about, disagreed over. The activities of these ordinary people, during the year prior to their arrests, have a place in the history of our times.

Kempton sets out to describe what our epoch does to those who would be its radicals. The conditions that move black Americans to rage, to hatred, to despair, are real. Every day they see how a society consigns their sons and daughters to a lifetime in the shadows. How much can a seminar paper or a scholarly study on racism and poverty add to what we see when we gaze across 128th Street?2 In this respect the black radical reveals more than his white counterpart. While I will not compare intensities of commitment, I nevertheless suspect that opposing the Vietnam war cannot consume as much of one’s life as seeing the day-by-day disintegration of one’s children. Indeed the reliance of white radicals on books, articles, and abstract ideas may suggest its own ambiguities. I am grateful to Kempton for staying on Center Street instead of traveling to Harrisburg or Seattle.

The raison d’être of radicalism is action. So in the United States, at the turn of the 1970s, what do you do if you are black and persuaded that yours is a sadistic society? Quite clearly the black masses are not ready to rise. The Panthers used Gilo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers as a textbook; but its lessons assumed the presence of brothers and sisters prepared to face tanks in the streets, and a country to be taken over. Neither Harlem nor Oakland nor any other American slum has so quickened a consciousness. So a small group concluded that the tactic for the interim must be guerrilla warfare for the awakened few. Yet the question still remained, what do you do to demoralize your oppressors? One route—on which a book is yet to be written—has been that of the supposed “Black Liberation Army,” or at least those persons who have cold-bloodedly killed several New York police officers. Terror of this sort has proved effective when you have a local majority on your side and troops of another nationality are occupying your territory—witness the French Resistance, the Stern Gang, the Irish Republican Army. However, taking shots at American policemen does not fit this formula; indeed, such gestures will bring even greater repression.

But the Panthers who stood trial in New York never considered anything even approaching assassination, either of outsiders or, for that matter, of their own members. Of that we can be sure, considering how carefully their every interchange was observed by the police. They were, rather, similar to other American radicals, such as Philip Berrigan, Elizabeth McAlister, and the Chicago and Gainesville defendants, who did not do much more than muse about kidnapping Kissinger, carrying slingshots to the Republican convention, and lacing Richard Daley’s reservoirs with LSD. For, as everyone now knows, the New York Panthers spoke of blowing up not bridges or tunnels or power stations, but the greenhouses at the Bronx Botanical Gardens. (The gardeners stood in little danger, for at best the group’s arsenal consisted of five sticks of dynamite in uncertain working order.) How tempting to remark that this is not radicalism at all, but the war games of children, played by those who have yet to learn the meaning of politics. Living with tragedy, can they respond only with dangerous farce?

Advertisement

But Kempton never patronizes his subjects or condescends, a difficult temptation to avoid in view of the bewilderment and incompetence in the Panther case. Nor does the book wallow in liberal guilt. Its success lies in the perspective Kempton brings to a story which could so easily be made to seem ludicrous. He affirms that black Americans have every justification for taking a radical position. But he also understands—sorrowfully rather than cynically—that we will not in our time see the events that radicals want. This apposition itself justifies the effort to chronicle an obscure political prosecution. By exploring the lives of a few already forgotten citizens, Murray Kempton has undertaken the most difficult and yet the most valuable way of writing the history of our time.

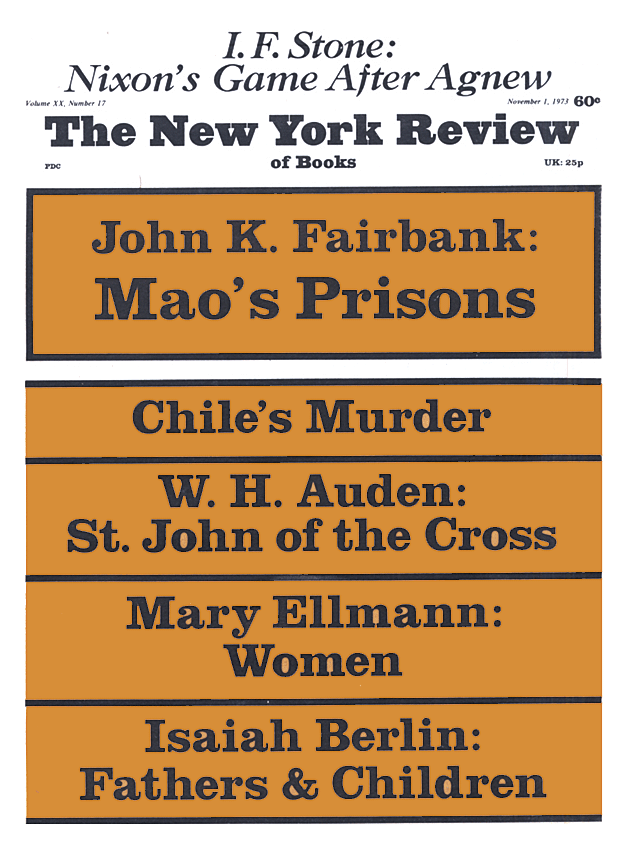

This Issue

November 1, 1973

-

1

Edwin Kennebeck’s Juror Number Four (Norton, 1973) provides a useful and intelligent account of what went on in the juryroom. Catherine Breslin’s article, “One Year Later: the Radicalization of the Panther Thirteen Jury,” New York Magazine, May 29, 1972, carries the story even further. ↩

-

2

Indeed the defendants were survivors; their chapters of autobiography are littered with the corpses of friends, classmates, and lovers who died early deaths. Their collective chronicle, Look for Me in the Whirlwind (Vintage, 1971), deserves much more attention than it has received. It is more than a book on a trial. ↩