In the global community of the postcold war world, freedom of individual expression is becoming a universal problem like food and energy. It is at issue on the Watergate and other fronts in the United States, and on the Sakharov-Solzhenitsyn front in Moscow, but will there be any Chinese Sakharovs? China is achieving technological development without political expression for the individual technician. The degree of individual freedom to be expected in the world’s crowded future is more uncertain in China than in most places because the Chinese are so well organized and so anti-individualist in custom and doctrine. Are they going to prove individualism out of date?

China is usually fitted into the international world either by a theory of delayed progress or by a theory of uniqueness. The first theory assumes that China has merely been slow to get on the path of modernity, but once launched will come along like all the rest of us with industrialization and all its ills and triumphs. The second theory, which of course is the stock in trade of most China specialists, is that China is unique and will never be like other countries. (Since China is obviously both like and unlike other places, this whole discussion is a great semi-issue in which each contestant must make his own mixture.)

The view that China must follow universal laws of development, which appeals to Marxists among others, can lead one to conclude that China’s growth in modern scientific scholarship still lags behind that of the Soviet Union, and so cases like that of academician Sakharov have not yet emerged in China but will do so in the future. Eventually, it may be assumed, a specialized scholarly elite cannot help having individual views and speaking out, but the People’s Republic is still at the stage of its evolution where egalitarianism is the dominant creed, education is to be only a matter of acquiring technical skills for public purposes, and in order to avoid the revival of the old ruling class tradition, no scholarly elite can be allowed to grow up in the universities. By this reckoning China, like the USSR, is on our track but has a long way still to go.

If one takes the other tack stressing the special character of Chinese society, one may conclude that the Chinese are far more sophisticated in their social organization and political life than we distant outsiders commonly realize. This view is compatible with the Maoist orthodoxy in China, which claims that the Soviets have lost the true communist vision while China retains it and can avoid the evils of capitalism including the American type of individualism.

From either point of view, China is seen to be setting a new style, achieving her own new solutions in applying technology to modern life. For example, helped by the press of numbers which makes automobiles for individuals inconceivable, the Chinese may escape the corrosive effects of automobile civilization. In such a crowded country, communities cannot be easily destroyed, and the apparent high morale of village life in the countryside betokens a people who can absorb a great deal more modern technology without having their local society disrupted.

In this view China is well rid of the Western type of individual political expression, opposed to it both because of tradition and because of present-day circumstances. Life in China will follow other norms than the Bill of Rights because the letter of the law and litigation through due process are still less esteemed than the common moral sense and opinion of the group, subordinating individual interests to those of the community. The mass of China is dense enough to permit this new Maoist way of life to be preserved there during industrialization, in spite of some growth of international contact through guided tourism. Given their numbers, resources, and traditions, the Chinese are obliged to create their own novel anti-individualist society. No one else has a model for them to follow, though the Soviets have offered the most.

Nevertheless, Western word-users of all sorts who appreciate their relative freedom of expression will continue to scan the variegated flood of China books for clues to the future of individualism there. Are all Chinese dutiful and interchangeable parts of Mao’s great production machine? What is the role of dissent in the society? What are its limits? How are dissidents handled?

China’s treatment of deviant individuals in labor camps owes something to Soviet inspiration but has developed in the Chinese style, not the Soviet. The contrast emerges from an unusual survivor account, by a Franco-Chinese who got the full treatment during seven lean years but learned how to survive in the system, and was discharged when France recognized China in 1964. His account is ten years old, from the time of troubles now attributed to Liu Shao-ch’i, before the Cultural Revolution.

Advertisement

Jean Pasqualini was born in China in 1926 of a French army father and a Chinese mother. He grew up with Chinese playmates, looking Chinese, speaking like a native. He learned French and English at French Catholic mission schools, and held the passport of a French citizen resident in China. In 1945 he worked for the Fifth US Marines as a civilian specialist with the Military Police, and later for the US Army Criminal Investigation Division until November, 1948. In 1953 he got a job in a Western embassy in Peking and was finally arrested during the anti-rightist campaign in December, 1957.

Under his Chinese name, Bao Ruowang, he then spent seven years of a twelve-year sentence for criminal activities in the Chinese communist labor camps, one of many millions undergoing Reform Through Labor (Lao Gai or Lao-tung kai-tsao), to be distinguished from the other multitudes undergoing Re-education Through Labor (Lao Jiao or Lao-tung chiaoyang). After de Gaulle’s recognition of the People’s Republic in 1964 led to Bao’s release, he came to Paris for the first time, where he is today a respected teacher of Chinese language.

In 1969 Rudolph Chelminski, the Life correspondent in Paris who had just spent two years in its Moscow bureau, heard Pasqualini’s amazing stories and began a three-year sparetime collaboration which produced this book. Chelminski soon “realized (to my surprise, I admit) that neither Jean nor the book we were developing was anti-Chinese or even anticommunist. In the camps he had been frankly employed as slave labor, and yet he couldn’t fail to admire the strength of spirit of the Chinese people and the honesty and dedication of most of the communist cadres he met.”

The book is indeed unique, probably a classic. Like William Hinton’s Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village,1 the story has been skillfully put together with conversations, personalities, and incidents made clear-cut and dramatic. It invites comparison with the accounts of Soviet labor camps, and the comparison goes in China’s favor. Pasqualini recounts a harrowing ordeal in grim detail but it is set in a social context of dedication to the revolution in word and deed. The individual is expected to submit completely and strive for reform, on the same ancient assumption that underlay Confucianism, that man is perfectible and can be led to proper conduct.

Pasqualini confirms the impression researchers gain from talking to Kwangtung escapees in Hong Kong, that the Chinese camps see little growth of an “inmate subculture.” Martin Whyte reminds us that in American prisons today, as also in Soviet labor camps under Stalin, “the very coercive nature of the prison gives rise to an informal but powerful subculture which dominates the lives of prisoners and obstructs rehabilitation.”2 In the Stalinist case little stress was put on political re-education. Instead, the genuine criminals were put in charge of the political offenders, which possibly fostered production but not reform.

These evils the Chinese avoided. Pasqualini says that Chinese camps are so effectively run that they make a profit, because the Chinese, unlike the Soviets, realize that mere coercion cannot get the most productive performance from prisoners. The Chinese system in Pasqualini’s time used hunger as a major incentive plus mutual surveillance, mutual denunciation, and self-evaluation as automatic disciplinary measures. But the main emphasis, after labor, was on study and self-improvement. For most of the millions who enter the labor camps the experience, he says, is permanent; few ever return to civilian life. Instead, after their terms have expired they continue as “free workers” in the camp factory with some extra privileges but under the same tight discipline, pretty thoroughly adjusted and continuously productive.

After his arrest Pasqualini, or Bao, to use his Chinese name, spent his first fifteen months in an interrogation center. Under the warders’ close supervision, his dozen cellmates constantly exhorted one another to behave properly and with gratitude to the government for their chance to expiate their crimes and achieve reform. The government policy was “leniency to those who confess, severity to those who resist, expiation of crimes through gaining merits, reward to those who have gained merits.” The key principle throughout was complete submission to authority.

Early on Bao was led into a torture chamber full of grisly equipment, only to be told after his first shock that it was a museum preserved from the Kuomintang era. Throughout his experience physical coercion of prisoners was strictly forbidden. Prison life was thoroughly organized to occupy nearly every waking moment. Prisoners moved at a trot with their heads bowed, looking neither right nor left. They followed punctilious daily routines, including periods for meditation when they sat cross-legged on their beds “exactly like a flock of Buddhist monks.” Five days a week were occupied with confessions and interrogations, which each man worked out laboriously for himself with his interrogators. Bao wound up with a 700-page statement. Sunday was free for political study and Tuesday for cleanup, including passing around “a little box for toenail parings” collected monthly and sold for use in traditional Chinese medicine. The proceeds paid for a movie every four months. During fifteen months in this detention center Bao “ate rice only once and meat never. Six months after my arrest my stomach was entirely caved-in and I began to have the characteristic bruised joints that came from simple body contact with the communal bed.” Vitamin deficiency led to his hair falling out and skin rubbing off.

Advertisement

“Facing the government we must study together and watch each other” was the slogan posted on the walls. Occasionally the study sessions would be punctuated by a struggle meeting, “a peculiarly Chinese invention combining intimidation, humiliation and sheer exhaustion…an intellectual gang-beating of one man by many, sometimes even thousands, in which the victim has no defense, not even truth.” A struggle can go on indefinitely until contrition has been achieved. The only way out is to develop a revolutionary ardor and the only means for that is by full confession. When it was decreed that all prisoners should take a two-hour nap in the summer afternoon, “anyone with his eyes open would receive a written reprimand. Enough reprimands and he would be ripe for struggling. We were very well-behaved. Model children.”

When his interrogation was finally complete, Bao was shown the dossier of accusations against him. He found that all kinds of friends and colleagues had submitted their hand-written denunciation forms about him. It was now his turn to denounce others. “We want you to reform, but how can we consider you to be truly on the good road unless you tell us about your associates? Denunciation of others is a very good method of penance.”

Another of the devices for inhibiting prisoner solidarity was the system by which cellmates were obliged to settle the ration due to each cell-member, based on his own proposal and everyone else’s assessment and vote. No one could help a friend eat well, any more than he could avoid struggling against him with hateful denunciations.

Finally, Bao came to trial: “You are not obliged to say anything. You will answer only when you are told to. We have chosen someone for your defense.” The defense lawyer made a simple point, “The accused has admitted committing these crimes of his own free will. Therefore no defense is necessary.”

While awaiting sentence Bao was transferred to a transit center known as the Peking Experimental Scientific Instruments Factory situated next to the pretty Tao Ran Ting Park. Here he found that productive labor consisted of folding three-foot by two-foot printed sheets three times onto themselves to make book pages. The communal plank beds that nightly held twelve men side by side were dismantled and used as work space by day. The beginner’s norm of 3,000 a day was difficult to achieve at first but the average output was 4,500 and the target of the government 6,000. One ate a ration according to one’s performance. Beginners got about thirty-one pounds of food a month. Folding 3,000 leaves a day got one forty-one pounds a month. Work was from 5 AM to 7:30 PM. After a bit Bao got up to 3,500 leaves a day but his weight had dropped to 110 pounds. By the time he left the transit center he had few fingernails remaining but he was folding up to 10,000 leaves a day.

He finally received a sentence of twelve years imprisonment for reform through labor. His experience was fairly straightforward, perhaps because of his foreign nationality. In many cases a sentence, say, of ten years for the record is not announced to the prisoner, who may be led to believe it is twenty years or life. Subsequently he is given apparent reductions of sentence. By the time he is said to have served his sentence and become a free worker, though still in the camps, he feels accumulated gratitude for these apparent reductions of sentence.

A year and a half after his arrest Bao had a six-minute visit from his wife and one of his children. After being thoroughly searched—the linings of jackets slit open with a razor blade—the prisoners receiving visitors were instructed to speak in a loud voice across the plank separating them. Even this was better than a “dishonorable visit” when a recalcitrant prisoner was visited by family members specially brought to upbraid and admonish him to improve his conduct.

Prisoners in the 1958-1959 period were caught up in the campaigns of the time. Urged to write down his feelings about his own sentence and crimes, Bao made the mistake of responding sincerely and stated that the government’s alleged concern for him seemed to be a sham. All it really wanted from the prisoners was cheap slave labor. Soon this was used, at the end of the ideological reform campaign, to make him an example and he was put in chains in solitary in a cell about four feet long and four and a half feet high, room enough to sit but not to stand or lie down, with a permanently lit electric bulb overhead. At mealtime his handcuffs which had been behind him were changed to be in front, which was better than having to lap up the food ration like a dog. With his hands bound, however, he could hardly fight off the lice which soon flourished on his body.

After five days he asked to speak with someone from the Ministry of Public Security, to whom he said that the government had told him lies when the warder had assured him that honesty would be rewarded and his worst thoughts should be put on paper. “Having obeyed because of my profound confidence in the government and the Party, I was now being rewarded with solitary. Where was my sin?” This got him out, since “the Maoist order is inordinately proud of its own special sort of integrity.”

In September, 1959, he was transferred to Peking Prison Number One, the model jail where he found it “almost shocking to be treated like a human being.” The food was now good and plentiful and the warden sympathetic and humane. “Maybe it was the classical Pavlovian approach…his decency after two years of pain and humiliation was absolutely inspirational.” Here Bao put together his first full-scale ideological review. In this the principles of criticism and self-criticism are the same as for citizens outside. Confession should be spontaneous, the moment one commits any error. Others should be quick to assist anyone who makes a mistake so that he can recognize it better. Only if this fails is the individual pushed into struggle or solitary. In this statement Bao typically declared that his sentence seemed most lenient and just, confessed that he had disregarded the regulations that prisoners should always move in groups of two or more because several times he had gone to the latrine alone, and other times in study sessions he had not sat in the regulation manner or again he had talked during working hours.

Worse, he had been reluctant to report on persons who had been good to him, although actually reporting on others is a “two-way help: it helps the government to know what is going on and it helps the person involved by making it possible for him to recognize his mistakes.” He finally wound up by pledging to listen to the government in all things. At this time he realized he was only protecting his skin but “before I left the Chinese jails, I was writing those phrases and believing them.” As one old-timer told him, “The only way to survive in jail is to write a confession right away and make your sins look as black as possible…but don’t ever hint that the prison authorities or the government share any of the responsibility.”

By this time Bao was diagnosed as having tuberculosis and so spent a couple of months in an infirmary. From there he went to the Ching Ho camp for an outdoor life in the fields.

China was now entering the hard years of malnutrition, and the ration for prison farms naturally suffered. Bao found himself in a settlement of the old and weak where discipline was less strict, there were few norms and hardly any guards. As one of the able-bodied gang he worked on the pig manure detail and learned more about how to survive, for example by snuggling up to the pigs on cold nights.

With their low rations the prisoners he had seen thus far had never shown any sexual problems. But one day the camp barber was found to have seduced a feeble-minded young prisoner. Within hours the barber was brought in front of the assembly, denounced, condemned, and shot, his brains spraying over the front rows of the audience. “I have read of men being raped in Western prisons. In China the guilty party would be shot on the spot.”

In October Bao went with a selected group on the long trip to the North-east as a volunteer for the famous Hsing Kai Hu farm in the barren lands north of Harbin on the Soviet frontier. “Everything seemed abundant up here in Manchuria and strangely unprison-like.” The vast confines of the camp area encompassed fields, barracks, watchtowers, villages. “Everything seemed orderly and well-tended.” The inhabitants welcomed the newcomers like human beings. The food seemed first-rate. “Improper attitude rather than low production was the criterion for cutting a man’s rations…. After a few days in the fields I was truly happy to be in the barren lands.” Unfortunately it was found that he was a foreigner in a sensitive frontier area. Together with a couple of over-seas Chinese he was sent back to Ching Ho after only a brief experience in this invigorating environment.

The fall of 1960 found Bao still struggling to get enough to eat as the winter cold came on. Work was reduced to six hours a day. Conditions became truly desperate as the food supply dwindled. The camp experimented with ersatz to mix in the food in the form of paper pulp. At first this made the steamed bread bigger and more filling, but soon the whole farm suffered “probably one of the most serious cases of mass constipation in medical history because the paper pulp powder had absorbed the moisture from the digestive tract…. I had to stick my finger up my anus and dig it out in dry lumps like sawdust.” Another effort was to use marsh water plankton but this proved unassimilable. Still the warden was able to give them a New Year meal with rice, meat, and vegetables.

By 1961 Bao had achieved a high ideological level: he believed what the warders told him, respected most of the guards, and was convinced that if the government didn’t exactly love him it was at least doing everything within its power to keep him healthy in the bad times. In this season of semi-starvation the warders put rumors to rest by taking all the prisoners through their own kitchen to show that they too were living on sweet potato flour mixed with corn cob ersatz. “Chinese communists are often painful fanatics but they are straight and honest.”

Being a foreigner Bao realized he was the only one who stood any chance of ever getting out of China and therefore he had avoided breaking the rule against foraging for extra food. But he developed low blood pressure and other signs of vitamin deficiency. Now his cellmates taught him the tricks of foraging, stealing a turnip, or reconditioning the discarded outer leaves of cabbages to balance their diet. One of his cellmates gave him some corn that had a strange powerful taste like ammonia, foraged from horse droppings. By May, 1961, he was ill and in the infirmary with amoebic dysentery and anemia, well on the way toward extinction. But cellmates kept bringing him special food, products of their foraging. After he made it back to health and work again, one of them explained, “You’re the only one who’s different, Bao. You might get out the Big Door someday. It could happen to a foreigner but not us. You’ll be the only one who can tell about it afterward.”

Getting back to work in summertime in the paddyfields it was possible to catch frogs. “We would skin them on the spot and eat them raw. The system is to start with the mouth and the head comes off with the spine.”

One cold night instead of going 200 yards to the latrine, Bao pissed against a wall. “I had barely finished when I received a very sharp and swift kick in the ass. It was a warder. ‘Don’t you realize the sanitation rules?’ he demanded. He was quite right but it was the ass of an ideological veteran he had kicked. ‘I admit I am wrong Warder, but I had the impression that government members were not supposed to lay hands on prisoners. I thought physical violence was forbidden.”‘ The warder admitted his mistake, said he would bring it up at his own next self-criticism session, and sent Bao back to his cell to write a confession. Bao thereupon confessed that his pissing on the wall had demonstrated “a disregard for the teachings of the government and a resistance to reform…displaying my anger in an under-handed manner…like spitting in the face of the government when I thought no one was looking. I can only ask that the government punish me as severely as possible.” The result was no punishment.

By 1963 Bao was so ideologically active and correct that he was trusted to be a cell leader. “With the zeal of a true convert I began searching for new ways to serve the government and help my fellow men.” Among other things he went barefoot in summertime to save the government shoe leather. Finally, however, he confessed to having bad thoughts: that if Chinese consuls demanded access to their nationals in Indian camps (as they were doing just then), the French consul should have access to Bao in China. Bao said he knew such ideas were wrong but still he had them. “I would not be sincere,” he wrote, “if I kept them hidden from the government.” His ideological reform seemed to have taken hold of him so completely that it probably contributed to his release as a French citizen when Sino-French diplomatic relations were established in 1964.

Other foreigners and Chinese who had lived abroad, as Bao had not, were unable to achieve his degree of conversion and acceptance. He records many bitter personal tragedies among this class of prisoners, whose foreign back-ground made them eternally vulnerable.

Chinese intellectuals in general seemed unable sufficiently to abjure their individualism. “Like the Soviets, the Chinese ideologues cordially despise and mistrust the intelligentsia because of its irritating tendency to form its own ideas.”

American journalists, as the most full-blown form of individualism-in-action, naturally seek to find it abroad. Warren Phillips and Robert Keatley of the Wall Street Journal visited China separately, each for several weeks in 1971-72. In addition to recording the data of China’s material development, they also questioned the Chinese they met about their personal circumstances and satisfactions. Typically, the Chinese hosts were most aware of their people’s material success in overcoming their old problem of peasant destitution, while the visitors were most concerned with the American-type question, “What goes on in the minds of those men and women on the bicycles or pulling the carts?” Phillips and Keatley cite many instances of friendly enthusiasm toward Americans and orthodox answers to political questions, but they found no explicit demand for greater political self-expression. As a matter of fact, they didn’t really get behind the mask. Like so many of the rest of us who have visited the People’s Republic, these able and culture-bound reporters looked for symptoms of individualism but did not find them.

Able China specialists, being more aware of Chinese values and more impressed with the revolution, may not look at all. In A Chinese View of China John Gittings’s selection of thirty-four translations from Chinese sources is intended to let the reader listen “directly to what the Chinese themselves have to say.” The result, of course, is a contribution from Mr. Gittings as well as from the Chinese, since as he says, he has “tilted the balance” to show the “attitudes toward their past and their present which are held by the Chinese in China today,” and who is to gainsay him? Every China specialist has to decide who are the Chinese. Mr. Gittings’s selections do indeed seem to reflect the current Peking view of history.

After half a dozen miscellaneous items on ancient China, the modern history selections reflect the black and white views of revolutionaries who may not know much of their own history but do know what they don’t like. Everything before Mao is shown to be either an evil from abroad or a footless effort by ineffective people at home. There is one of Commissioner Lin’s undelivered letters to Queen Victoria and an account of Mandarin sell-out to the British at Canton. A British imperialist voice, that of Consul Swinhoe, is quoted as a non-Chinese exception to indicate foreign rapacity, and then there is a passage on the evils of the coolie trade to Cuba. From this we move to the reform decrees of 1898 and folklore about the Boxers. The section ends with the railway engineer, Chan Tien-yu, a rather meaningless Sun Yat-sen piece, the end of Yuan Shih-k’ai, Mao’s article on the great union of the popular masses, a piece from Lu Hsun and another on foreign cigarette companies exploiting farmers.

Notably lacking in this selection is any reference to the considerable efforts of the Chinese leadership in the late nineteenth century to appraise the foreign problem, begin some industrialization and defense, and debate the whole question of modernization. The late Ch’ing generation is simply non-existent in this record. Even May 4 gets rather short attention, over-shadowed by the Chairman.

The contemporary selections contain items from Mao and others on the Long March, land reform, minorities, medical progress, and the exemplary Lei Feng, so humble but so remarkably eloquent. The book winds up with Red Guard documents, and a section of facts and figures. In sum, we learn that Peking has an idealistic enthusiasm for its own models, methods, and achievements. The book is illustrated and on the whole quite informative. (Unfortunately one fake picture has slipped in, labeled as “a local magistrate’s court,” taken from A. J. Hardy’s John Chinaman at Home [London, 1905]: a photograph of what is obviously a theatrical scene from a play with lictors in comical hats standing over a so-called magistrate with two culprits kneeling before him—a magistrate’s court such as never was, except for stage purposes.)

From what the Chinese themselves say in Mr. Gittings’s book, individual political expression is a nonproblem. Only the great collective effort could have remade China. What happens when higher education produces a stratum of highly educated people is a problem for the future. We can be confident it will be dealt with, when it arises, in a Chinese way.

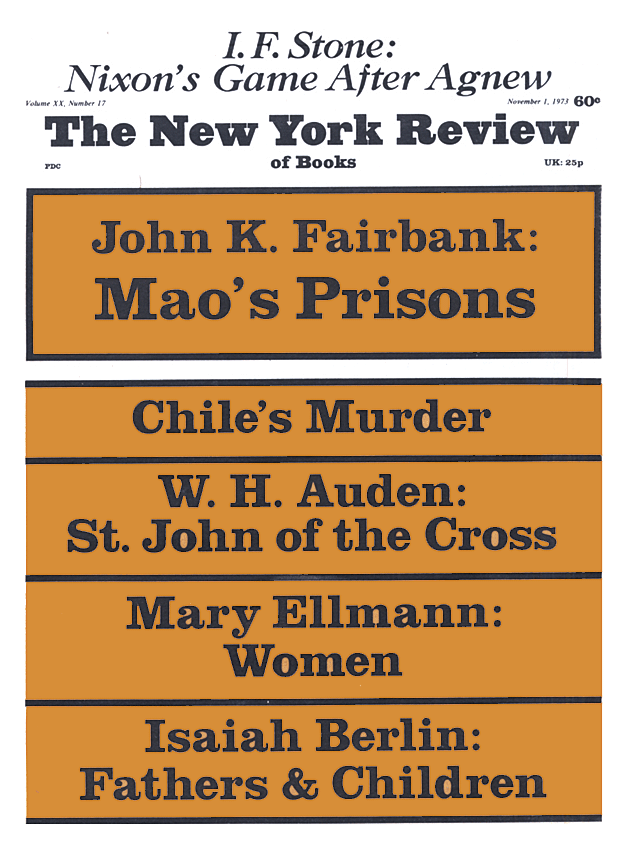

This Issue

November 1, 1973