Timon enters the space, a space as public and indiscriminate as a street. He is surrounded by people and yet without a setting. His claim to the space is scarcely greater than ours, the audience. Everything is bare and yet disorderly, not at all neat, not cool. Geometry is a statement, expensive; this space is a negligent, empty mess. There are sandbags, objects without character, defiant instead, merely useful to sit on, to form a circle for the dinner parties that are the peculiar and essential symbolic actions of Timon’s life. The sandbags are not attractive; they are just sand, dirt and absence. The bareness and the omissions are not in themselves to be called interesting, unless their interest is to make us happy that the scenic hole, the theatrical blank, is not to be filled with Greek tunics, Shakespearean ruffles, and page boys carrying platters on their palms.

Nothing is clean, shapely, pure in its quiet. It might be a rehearsal—those periods without illusion when the actors seem locked in their imperfect private lives, their faltering selves. No, it is not a rehearsal. Everything trembles, becomes tense. The simplicity is not an experiment, a trick, educational. It would be a disaster to look upon it in that way. The simplicity is real. When there is no money it is not necessary to scorn it.

The house is filled. It is a Sunday afternoon. The audience has waited outside in the cold drizzle for quite a while. We are in St. Denis, a working-class district in Paris. Communist posters and beautiful gray, worn stone buildings whose windows form a glimmering triangle as the streets narrow to meet a crossroad. Bouffes-du-Nord is the name of the theater and the place is a part of the manner in which this outstanding event, shaped by Peter Brook, seizes the public attention, defines itself. The building is a site, unredeemed, not stripped down but instead shaking in an ornate, interesting decay. It is a dingy, bankrupt, and splendid old structure with a dome of blackened, cracked glass. Its interior walls are flaky and stained; black grime and patches of white plaster melt into each other without renovation or restoration. It is a face in eruption and the holes cut into the walls so that the actors may appear and disappear from a height—these holes are like decayed teeth. The space itself, there, works on the spirits of the spectators as a teasing negative accepted. Necessity and creative will meet; the encounter is an achievement and lack is of course almost natural, not to be considered. It is a question then of something else, beyond, further. Luxury and illusion give way; easily too.

Timon itself, Shakespeare’s play, is in a state of reduction, at the least unrevised, thin in spots, late. It is perfectly served by the thrift of the staging, the challenging scantiness. Nothing would be worse than gold and silver, cloth from the ancient world, gilded sandals. The banquet scene with its Cupid, lutes, and Amazons is given by suggestion almost, without luxe. Instead a moody, hashish, blurred atmosphere, high, shrill sounds from the Arab quarter and mercifully no orgy or spot of nakedness standing out from the surface like a pimple upon which we are to gaze without pardon. The riches, the waste are all in the mind.

Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens is about the philanthropy the rich confer upon each other. (“O what a precious comfort ’tis to have so many like brothers commanding one another’s fortunes.”) The parties, the gifts, the courtesies, the lavish impulses plainly gratified—all of these carefree gestures to be underwritten by painstaking, by obsession. Yes, one’s whole life may be a benefaction distributed with no thought of necessity. With Timon, as with so many positioned thus by luck and inclination, it is the thing itself to some degree, the social contract also, and the aggressive planting of gnarled, complex roots of obligation. The generosity has in it a random quite sharp competitiveness and it is by agile calculations that one keeps ahead. Timon is very much on the strain in this matter; he is watchful, quick, serious. “No gift to him / But breeds the giver a return exceeding / All use of quittance.”

There is only the giving, the parties, and, of course, the previous consumption by the giver. One must buy a jewel in order to press it upon a friend who does not need it. This is all we know about Timon, nothing else. Generosity, or wastefulness, is his definition at the beginning and misanthropy is his definition at the end. He is an attitude and each comes to us in the midst of its flowering, without any preparation or backward glance. We accept it, if we do, because prodigality is indeed common, perhaps more common than greed, but certainly not more than selfishness. It is in no way contrary to selfishness, either, and the cynic sees the connection with a ready clarity.

Advertisement

Timon does not boast of his heavy habit of giving. He has style, the style that puts a glaze on his ruling passion. His social nature sits upon him comfortably, like a pair of blue eyes. He is refined, offhand, and it is sometimes hard to discover where his true pleasure lies. In diversion or just in the satisfaction of an unaccountably strong impulse? The happy days of liberality pass in the purest courtesy; it is the misanthropy to come, when his friends prove stingy and indifferent to his run of bad luck, his shrunken fortunes, his classical reversal in the shape of bills come due—it is at this moment that Timon seems almost coarse. His insistent and intense hatred of the perfidy of man comes upon him suddenly, like an ugly drunkenness. This outrageous defensiveness baffles us. When he is still the giver rather than as he becomes, briefly, the suppliant, the petitioner, Timon is occupied with all the veiled and difficult reticences of the interesting host.

Flattery: in constructing the moral air of the play we are reminded that prodigality and flattery are instant friends. This is the way things go in society. “He that loves to be flattered is worthy of the flatterer.” Yet one of the striking ways of Timon is his need to treat extravagant praise and attention as if they were the dreaded reciprocity his nature and his enterprise are so set against. The jeweler, showing a fine gem, remarks that Timon would enhance the beauty of the stone in the wearing of it. This is quickly dismissed by “Well mocked.”

Flattery is a challenge. The proper turning away from it, undercutting, diminishing it without offense or vehemence, is a social grace sweeter even than the swift determination to keep ahead in the race of hospitality. Ventidius, who has been made rich by the death of his father, tries to repay a debt to Timon. The repayment is refused along with praise for the refusal. Timon draws back, fastidiously, abruptly from the compliments. “Nay, my lords, ceremony was but devised at first / To set a gloss on faint deeds.”

Timon in Paris: he is young, thin, not tall. His presence is such that it is not out of order to speak of him as beautiful. An unexceptional, unflawed face. He is wearing a white linen suit. It is the romantic gaze that surprises, dominates the space, draws you toward him, toward the inward young man of the nineteenth century, found on a soft, lazy afternoon, approaching his sorrow. It is said early that through Timon one may “drink the free air.” This is more than his ruling liberality, his obsessive bestowing; it speaks also of the atmosphere of an ineffable, unattainable wish, a memory of the golden age. Timon seems to move in a sunlight very clear and fragile. The senators, the painters and poets, the strangely conceived Apemantus (“a churlish philosopher”) all have a good deal of lead in their natures. The leaden breathe the free air—in sloth and a bit of suspicion.

But who is the Timon in St. Denis? He is not an Athenian and although he speaks his lines in French he is not a Frenchman. He is not Shakespearean; still he is Timon, or a Timon. The world is waiting for him as the play opens. He appears to be the only person in Athens with imagination. He is on everyone’s mind—jewelers, merchants, soldiers, “friends.” They form a gathering that gives him his substance but none of them is quite real. They simply trail this curious young man through his moods.

His gaze is graceful, and the faint smile, the pleasingly self-absorbed lightness of his gestures, are suitable to the monochromatic drama, the slow and insistently peculiar single theme. Timon, the splendid young actor (François Marthouret) in Peter Brook’s production, greets the world in the manner of a young prince, an heir, but a prince with the gentle, strangely caressing and careless charm of a flawed inheritance, an irregular line. Yes, he is a rich and pleasing prince—one whose mother was an actress or a model. Thus he lacks, we think, the ingrained prudence, the caution, the patience of the pure line with its marbleized suet of inherited economies and thrifts.

Timon is dreaming, like the Prince von Homburg, who also had his temper tantrums, his indiscreet princely impulses, his lovely forgetfulness of the rules. Timon is a romantic, a spendthrift, full of longings for something perfect, if only the perfect gift, the dazzling charity. Jewels and horses, dowries and fanciful favors take up his time, but through it all he maintains, for himself, a kind of chastity, as if he were too young for lust. Or perhaps something warns him even at the first that the acute, burning misanthropy lies waiting for the exhausted innocent and the weary aesthete.

Advertisement

The play is an exceedingly cold one but there is a tropicality in the Paris scene, the tropicality of the desert perhaps. Athens is corrupt; it is a city of solid usurers and fat hypocrites. You can think of it as the Greece of the colonels if you like, or so the comments made by Brook on the text suggest. But the real stage makes of the play a pastoral, a dreamlike, empty, poor place, filled with ragged “senators” and unlikely “lords” and black companions, and a small, brown, beautiful, weasel-faced “putain” and another, large, tall, screeching. It is an arid playground with luxurious words and real dust on the sleeve of the master misanthrope. The final Timon is a raving, wounded lover of life who falls into reality with a cry of “No!” and who, betrayed, prepares for a ritual suicide. “A madman so long, now a fool.”

Money is merely an idea, an ornament to Timon. Gold is a joke and in the end all it can give you is a lesson. Timon has no family, no history. We are surprised that even the foolish senators, facing defeat by Alcibiades, should urge Timon to return from his bitter exile to “take / The captainship, thou shalt be met with thanks, / Allowed absolute power, and thy good name / Live with authority.” This is madness. The young man digging his grave by the sea has never had the slightest use for affairs of state, is no more honest than his creditors, and is so moody in his swings from courtesy to abuse that his “heroism” can only be that of the romantic, the personal. Even when his creditors are at the door in search of his “desperate debts”—desperate because a “mad man owes them”—even when he descends to acknowledge his unbearable change from giver to beggar, Timon is a hurt and weary youth, his love rebuked. He can only act, not as a leader of Athenian society, but as an actor, on the stage.

His plan is not to create money, but a dramatic impression. The invitation goes out for the last banquet. He who is now “naked as a gull” invites the old heavy feeders to open pots filled only with water. It is a gesture and the young man, poised like a dancer, flashes his eyes and splashes the water around the circle of sandbags for the “dogs,” as he now sees his friends, “to lap.” The guests make off, hardly caring, looking for their hats, pulling themselves together. It is all over for Timon. The gesture was not sufficient.

Early we had been warned that when fortune changes there will not be one of the former friends “accompanying his declining foot.” And so it proved to be, although the servants are loyal. Timon leaps into misanthropy, without a delaying moment of study. He is quick to assume his role, his place in history: he is a misanthrope, high, special, complete. Plutarch says he “embraced with kisses and the greatest show of affection, Alcibiades, then in his youth.” But it was a show, a performance even in the earliest recording. His reason—the hovering paranoia of the stabbed romantic. He embraced Alcibiades because he knew that the soldier would “one day do infinite mischief to the Athenians.” And then, near the grave, Timon will live by his most successful turn as an actor—his invitation to any Athenian who wishes to come and hang himself on the fig tree before it is cut down.

Timon is an attitude and in the end he is drowned by words. He does not speak of aches and hunger and loneliness; he speaks of his attitudes, of what he has in a flash learned about the squalid nature of human beings. He invites the most terrible sufferings for mankind and councils children, “To general filths / Convert o’ th’ instant, green virginity! Do’t in your parents’ eyes!” Humanity has not harmed Timon. The ingratitude was local, limited, and we had not expected him to keep such a deep accounting or to extend his demands so widely. He and Apemantus have a dialogue extreme in its pettiness. The Paris Apemantus is black and has a lilting accent, perhaps that of a North African. He is a wanderer and carries a burlap bag on his back, along with the disillusionment that Timon sees not as philosophy but as ressentiment. Timon, having betrayed his own fortune in the manic spending, reminds Apemantus that his long melancholy is not disinterested. Apemantus has never clasped “fortune’s tender arm,” and so he mistrusts the world merely because he was “bred a dog.” Here the snob passes the day. “Dog” as a word is everywhere in the play. The lowly dog, outcast, ignored, hunting for the scraps of life, seems to fill a place in the dreaming mind; the image is firmly locked behind the eyes.

Timon is a parable or a fable, but what is its instruction? “Here lie I, Timon, who alive all living men did hate.” An odd idea. The lottery money is spent, but it is not the loss, the deprivation and decline, that turn the heart to rage. To understand Timon is to imagine his own false memory of a garden of love greater than life, his own dreaming of a plenitude so greatly flowering that he himself seemed to direct it, command it. But it was not Eden after all. It was only another Saturday night with one’s own set; and at the end the dishes, the ashes, the quarrels, the squeezing pain of repetition, the hope that was a lie to ourselves more than to others. “One day he gives us diamonds, next day stones.” This is a comment from the outside, but it is the understanding of the host also. All those evenings he had been writing his epitaph, breaking the stones of the grave with his teeth.

This Issue

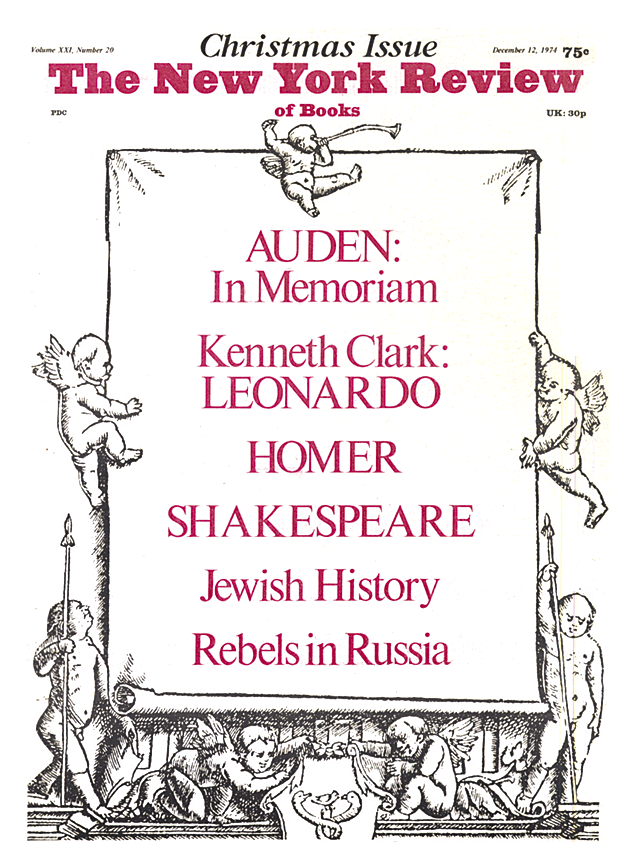

December 12, 1974