In response to:

What Did the Romantics Mean? from the November 1, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

I would like to comment on Charles Rosen’s article “What Did the Romantics Mean?” in your November 1 issue.

It’s interesting to see how Charles Rosen perceives Caspar David Friedrich’s personality and art, for the many different attempts at interpreting these, and the history of the understanding and misunderstanding of his art, are part of the Friedrich phenomenon. It confirms just that which the reviewer of my necessarily concise explanations in the London exhibition catalogue has tried to refute, namely that Friedrich speaks a very private language in his paintings, which veils the intended message more and more as time goes on, so that the superficial observer is held at a distance from that which was, for Friedrich, an inner necessity to express.

The reviewer writes of my interpretations that “we need not wait for his forthcoming book to protest.” He at least could have taken the time to glance at the appendix to the catalogue, where interpretations by Friedrich’s contemporaries are printed. If his friends Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert and Ludwig Tieck were in error, at least I find myself, in agreeing with them, in good company. And finally I can also rely on Friedrich’s own explanation of the Tetschener Altar to justify my method of interpretation.

Interpretations of the “great preserve” such as Rosen cited can only be presented as conjectures in the framework of a catalogue and may of course raise some doubts here and there. But they were intended as a stimulus to verify the findings in other paintings. The meaning of an abruptly ending avenue, for instance, becomes clear when one examines this motif in the artist’s total oeuvre. I have done just that in my recent book with all the various visual objects that appear in Friedrich’s work.

Helmut Börsch-Supan

Charles Rosen replies:

Börsch-Supan, understandably aggrieved, is unwise to call attention to the appendix of his catalogue. The documents which are printed there do not at all bear witness for his side in the matter upon which we disagree. He is mistaken in imagining himself in the company of Tieck and G. H. Schubert: neither of them claims, as he does, that the meaning of the elements in Friedrich’s art remains fixed from picture to picture.

The point at issue is not whether Friedrich’s pictures have religious and, sometimes, “allegorical” meanings (although that is a word whose meaning has often shifted radically, and was given different interpretations during Friedrich’s own lifetime). That much is fundamental and obvious and admitted by anyone. What is debatable is how these meanings are to be read.

Börsch-Supan claims that Friedrich’s language is “private”; but this is true only in so far as it is not a traditional one. It is astonishing and even sad that he has not drawn the logical and immediate conclusion: that the meanings of the elements of Friedrich’s language cannot be discovered as if they were parts of a traditional, completely public, but not yet understood tongue, by comparison and decoding. That is why the documented comparisons he promises in his forthcoming book hold out no hope for understanding. They represent the way of finding out the meanings of the traditional iconography of previous centuries, the traditional iconography that Friedrich, like most of his contemporaries, rejected because the meanings were “arbitrary,” imposed from without. They had to be learned, as Börsch-Supan proposes to learn Friedrich’s, and if he is right, then Friedrich’s pictures do not work. Börsch-Supan, in fact, can only illuminate Friedrich’s failures. Tieck, in a passage that Börsch-Supan does not print but which follows closely upon the one he does, calls attention to the failures, to the occasional works by Friedrich whose meaning is arbitrary, private, unrevealed through the pictorial forms.

Friedrich’s greatness—and he was a very great painter—lies elsewhere. Of all the documents printed in the appendix, the closest to Börsch-Supan’s view is that of the painter Ludwig Richter, who hated Friedrich’s work. It is the misunderstanding of men like Richter that made Friedrich’s work forgotten for so long. I see no point in trying to revive his view. Friedrich’s own opinion was that his language was not private but accessible. As he himself wrote (and as Börsch-Supan prints in the appendix): “Just as the pious man prays without speaking a word and the Almighty hearkens unto him, so the artist with true feeling paints and the sensitive man understands and recognizes it; while even the less sensitive gain some inkling of it.” There is not a word here of a private language. A comparison of Friedrich’s pictures will tell us how he conveyed meanings, not what meanings: only an interpretation of the forms of each work can lead us to that.

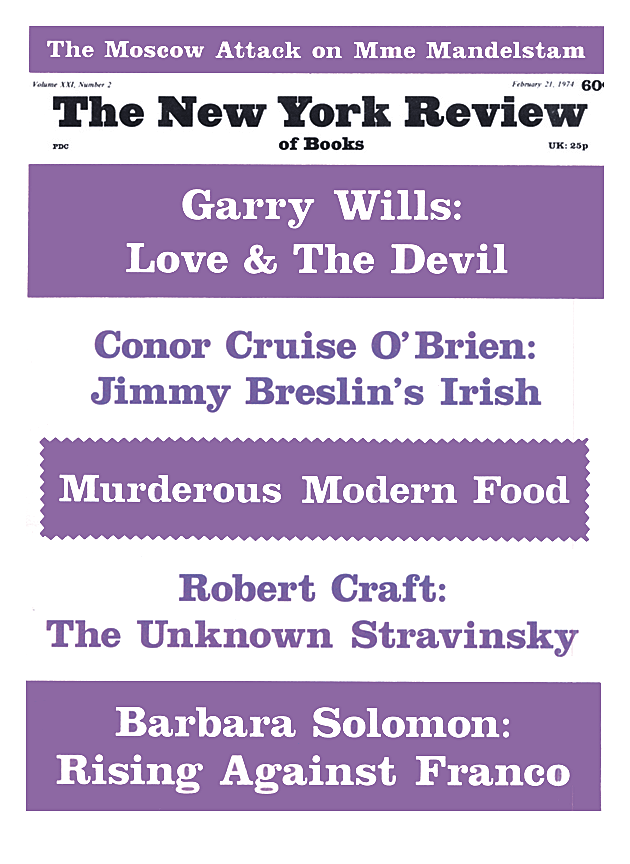

This Issue

February 21, 1974