We call her great, for her gift to us is not limited to the art of writing: it is the gift of a culture. I do not mean simply French culture and taste, but that she made certain discoveries with regard to the art of being which are indispensable to our lives, and which are regularly lost in the Western part of the world.

These discoveries came about as she got round the difficulties of her life. She became gradually the journalist of her own life, and in that journalism are strokes of genius that befit her to receive Nietzsche’s blessing. We can think of her as the prime exemplar of experiencing, who obtains truths which can only be got through the agency of things. She always found life new enough not to have to invent it; or we might put it another way, and say that she invented it by understanding it.

Because she teaches with her life, she is, fortunately, difficult to categorize, and belongs to philosophy as much as to literature. Her novels, which are brilliantly written, are as novels weak. By this I mean that when we read them we do not undergo a moral enlargement by reason of a vision whose effects are permanent, as we do with Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, George Eliot, or Henry James. She did not formulate in the abstract characters powerful enough to carry out schemes of redemption and enlightenment. That was not her way; it might very likely have seemed to her not truthful enough to what was all around her. And there is the danger, in finding one’s ultimate reach in literature, of losing the original talent with which one set out. If it had cost her her seership, then that would have been a loss so much more terrible than any gain in re-sizing her art that it is better forgotten.

The apprehension of sensual or magical situations is her province, enveloped alive in their own detail. Her supreme moment is the Annunciation; having learned to listen, she can hear when invisible forces announce their presences in mortal things. Should this sound too abstract for rational minds, we need only remind them of the grand pattern of evolutionary and spiritual behavior, and the humbler rhythms within the human body, and thereafter of the unseen, illogical, wholly real struggle between good and evil in the world, in order to regain their attention.

Given this basis for her writing, it will be seen that the more fresh life she lived, the stronger her work became. Life did not distract her from her thoughts; on the contrary, her real thoughts—the thoughts which were given to her—were outside, engrossed in life, and synonymous with it. She was never a mere clerk to her ego.

There were three marriages, a primordial mother a daughter a connection with the theater as an actress and dramatist, travels, a beautician interlude, books, and success.

The irony of the story is that everything is in that first marriage to the despised Willy, the literary man about town. The first marriage made necessary, and contained, the second, which was physical. And it made possible the third, which she could have missed by not having become quite herself, and which was a natural unhasty interlocking. Willy might have been a disaster for her, but she turned the whole thing to advantage, by going along with it, and investing in it, to try to see what it meant. In his favor is the fact that he imprisoned her in the heart of the right sort of cloud cuckoo-land. The other dusty cages contained Proust, Anatole France, Gide, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Schwob, Hérédia, Jarry; yesterday’s broken visionaries were only just off the pavements, Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, Gautier, Mallarmé. None of this would have been so immediately possible without Willy; he educated her and appreciated her, he stood between her and the literary businessmen who would have stolen her time from her as surely as he stole her books, and the money she needed to buy a life of he own.

It is worthwhile analyzing how a writing style of such beauty, and capacity, came into being; and how it was underpinned by psychological growth.

In a provincial schoolroom, the schoolgirl Colette wrote a note to a friend: “I scribbled down everything I could for her on a bit of tracing paper and launched the ball” (trans.. Antonia White). If we were able to unwrap that piece of tracing paper, we would find there stubs, particles, spotlessly clean, of the idiom of Claudine à l’école. It’s the primitive idiom of a little tomboy filled with joy and derision, whose manner of expression is kept pure by all the short cuts of laziness and illiteracy. Rimbaud’s early syntax is akin to it, but more carbolic. He cuts to ribbons, jams in a stone of a word—and it sends a sheet of light at you. The pages are made insufferable, invincible, by this kind of youth. But every additional year is dangerous to it, the blows soften the mind, and Colette was about twenty-five when she wrote the first Claudine book.

Advertisement

She had read a great deal of poetry by then. Baudelaire’s forest which vibrates like an organ appears two-thirds of the way through Claudine à l’école. She began, in general, to acquire the tone of the Symbolist poets.

The selection and treatment of descriptive detail, and the velocity of all action in this book, also suggest a reading of the masterly Poil de Carotte by Jules Renard, which had been published three years previously. A year before its publication, Jules Renard made a note in his diary about Colette, seen at the first night of a play with a long plait. The schoolboy Poil de Carotte spends most of his time at home; his quick-witted, hard-as-nails existence is aimed at us in a series of bulletins, anecdotes, and country images which are so exact that they appear harmless, when they are nothing less than implacable. A good example is the following description of a river: “It laps with a sound of teeth chattering, and exhales a stale smell” (trans., G.W. Stonier). Colette was almost equal to this and wrote, “Claire let off a laugh like a gas-escape” (Antonia White). She arranged her material in much the same way as Renard. Her sentencework was careful; verbs were already chosen with particular regard to the qualifying atmosphere they incorporated, their sense effect. Thus objects were “launched,” faces “grimaced,” and so on.

She was literary to the core, and her effects were calculated, as it was proper they should be. The calculation of her husband was of a different order when he asked her to put in “some patois, lots of local words, some naughtiness, you see what I mean?” Nevertheless, without his original suggestion, his conception of the book that might emerge if she set down some of her school memories, there would have been no book. He first had the idea of writing it himself, after lunching at her old school. Then in addition, without his efforts to make it scandalous, it would never have had the enormous worldly success which it had. Finally, he “arranged all the propaganda he could by all the means he could possibly think of”; he was a very great literary agent. As is well known, he published the book under his own name; having called it into being, he stole it away from Colette.

Margaret Crosland tells us that Colette’s signature was added to the contract with Willy’s; a significant fact. Colette knew, and her friends knew, who had written Claudine à l’école.

The deep psychological benefit to Colette of what followed must have been extraordinary. From that moment no matter what happened, underground, in the darkness, the place of fear and trembling, the gain had been registered—and that is where life truly begins. Despite an everyday existence of unchanged and indifferent quality, everything suddenly became possible, it came within reach. In the material world, it is extremely useful to become lucky before you can become unlucky. Your contemporaries get into the habit of liking you: and you are able to retain your daring.

Colette could not do anything about her success. She appears to have been a very young twenty-seven, with slight grasp of externals. She was in any case separated from reality by Willy. Evidently she found it extremely hard to credit things for what they were; she stuck fast, dreaming out her dream—and writing it down. In this condition she produced further Claudine books for Willy, and silently took an immense step forward. Her writing started to be very good. Twentieth-century Paris read her refreshing pages, pages of light temper, witty and clean-running; Willy, the taskmaster, struck in certain musicianly comments, and the books were all equally successful.

The drama behind her silent progression had been as follows. Her childish idea of herself had run on unchecked after marriage, and Willy had fostered it; in fact it was all she had. Suddenly she found out that he was unfaithful. The shock to her ego was more than it could bear; there was nothing inside capable of withstanding the blow, her personality was fragmented, and she collapsed into a nervous breakdown. At that moment she lost her childhood, and no longer knew who she was. Sido, her mother, came to Paris to nurse her, and helped her to pick up the thread of her own story again—and this is the very thread by which life hangs. When it was all over, and as soon as she began to write the first Claudine, she found herself, and could repair her identity. But this time a new self was in charge. It prescribed physical exercises for her body, and undertook the task of learning how to think, and be; the spirit stopped still and listened—an Oriental skill.

Advertisement

This mature work went on for eight years. From twenty-five until she was thirty-three, her thoughts wrote thoughtful letters to themselves. The mind restocked itself with itself. There was eventually so much life inside that she began mentally to live without her husband. And at the end of that time she had enough strength to move away from him physically. She had formed herself, and woken up. She was also capable of being alone if it was necessary.

Knowing how to be alone is a part of the wisdom of wild animals. Colette had never broken her bond with nature, and this includes the inanimate. The secret is commitment, detail, and alertness. Nature mystics would explain that you make friends with what is there; an animal, a plant, an object. Colette possessed herself of this knowledge and used it consciously throughout her life and in all her writings. Thus she arrived at the end of her time with Willy with a certain incomprehensible strength, and he was anxious to be rid of her.

Colette emerged as Pierrette, and with Willy’s help went on the stage. In the first book published as her own while still married, she wrote, “I mean to go on dancing in the theater.” It was called Dialogues de bêtes, a new genre. There was a rapport with Rudyard Kipling. The idea of animal conversations came most probably from his stories (which she mentions in Claudine à l’école), with their nicknames which described the characteristics of the animals, Stickly-Prickly and Bi-Coloured-Pythons-Rock-Snake.

The next development is profoundly instructive. Colette took her animals on the stage with her. She acted out of herself certain creatures, pure instincts, which had been locked up in a den inside for thirteen years. She personalized the animals of her subconscious, and drew its sting. All her natural desires, all her rage, instead of eating her internally—and one thinks of the expression “eating her heart out”—ceased to be harmful to her.

Becoming what she was in deeper levels of her mind brought about a physiological renewal. Her flesh was transformed by her psyche’s good health. Albert Flament described her later in life, for the process continued, “luscious arms—combing rapidly her short, thick hair, surrounding herself with a chestnut foam…. Eyes made for the stage, slanting upwards, and between their thick lashes, a look of youth, of joie de vivre, a spark of light so brilliant that it looks artificial….”

The years from thirty-three were those of the great test of strength. “Missy,” the Marquise de Belboeuf, was photographed standing with protective kindness behind Colette; one observes a somewhat sloping coastline, silk dressing-gown lapels, and the face of a manly, strong-minded nanny rabbit. Exactly what was needed. Colette was now playing George Sand, succubus and incubus, and although she would get into bed with Missy, she does not appear ever to have been deeply in love with a woman, which is an entirely different matter. She and Missy amused themselves immensely, and started scandals effective enough for fresh waves of publicity.

Colette continued her journalism, and contributed to Le Matin. In 1911 this great reporter and pierrette published La Vagabonde. It was a triumph. The book proceeds by scenes, dramatic reveries, and letters to plot through a love affair, nothing more, and in this case that is nothing less than everything. Motives and scruples are scanned familiarly by the inner eye. The quality of the sensibility is a lesson in itself; the needle quivers under the slightest vibration. Here is the parting between the heroine, Renée Néré, and her lover, Max. (Fossette is Renée’s dog.)

Fossette has squeezed between us her bronze-like skull, which gleams like rosewood….

“Max, she’s very fond of you; you’ll look after her?”

There now, the mere fact of bending together over this anxious little creature makes our tears overflow.

—(trans., Enid McLeod)

It is the homeliness and exactitude of the emotion that tells. It comes from a real life, cannot be got anywhere else, and is as fine as George Eliot’s humble drawn-thread work.

The following year Sido died. Colette lost so much of herself with this death that she spent the rest of her life writing about her. A second fundamental change took place. The spirit changes its condition of being, so to speak, it perceives there is another kind of life. After the baptism by death, Colette the wise woman was born, a person in authority.

She married Henri de Jouvenel three months later, and had a daughter by him. She had earned her daughter, and she could afford, psychologically and financially, to make this mistake. In any case it was irresistible, and had to be. Each side misconceived the other, and recovered from previously prepared positions, but slowly, going into years.

Chéri was published when Colette was forty-seven; and was said to be her masterpiece. It contains scenes which are of an emotional and aesthetic perfection; the marriage of symbolism and sexual experience. Yet it is static, even cold. In a large measure this is due to the central character, Chéri, who is perhaps a representation of an elemental, or nature spirit; he is two-dimensional and has no inner life. He comes from myth, from The Tempest, and all serious fairy stories. He is real enough, and can be described, like fire or water, but he will not go successfully into the fabric of human relationships which constitutes a novel. Placed at the center of a story, he petrifies the humanity, neutralizes the action, and renders all moral operation irrelevant. He is an essence and is imponderable. As a concept in himself, Colette knew she had made an important discovery. What she did not realize was that the nonhuman aspects of her subject were affecting her. The aesthetician predominates and repeats herself more often in this book than in any other, as though afraid to change the imagery that furnishes it, and only daring to rechisel. There are even moments when she thinks with words; low water for so great a writer.

Many novels, stories, autobiographical writings, and occasional pieces followed on; the articles for Le Matin are only now available in English (The Thousand and One Mornings). When at last Colette married Maurice Goudeket the foundations were solid, and from her happiness a flow of practical information comes to us; it is hard news. Her daily life has been converted by her into a raw material. She reports on it, as though she is a foreigner there. Now it can happen that between the reporter and the scene reported something is transmitted—and if it is written down immediately an uncanny electric truth is obtained. Normally this is only achieved by writing fast; or by being written by the facts. Colette was able to take on the wing such a revelation by mercury. It may be found in the atmosphere of the whole piece, its “entity,” or in half a sentence which brings our whole lives into focus. To paraphrase some words from the Koran, she says what she does not know. It is the quality that lifts her work into another class—another degree, the degree of master novelists, philosophers, mystics, and other grand masons of human development.

Margaret Crosland’s new interpretation of Colette is required reading for the Hamlets of London and New York. It is as good as her first study, Madame Colette. She has rethought her subject, added new facts, and filled in the Missy period between the first two marriages, and the early days with de Jouvenel. Willy emerges even more sympathetically. The book should be read on the spot, drained down to the dregs in one glance, bibliography, dates, italics, photographs, everything.

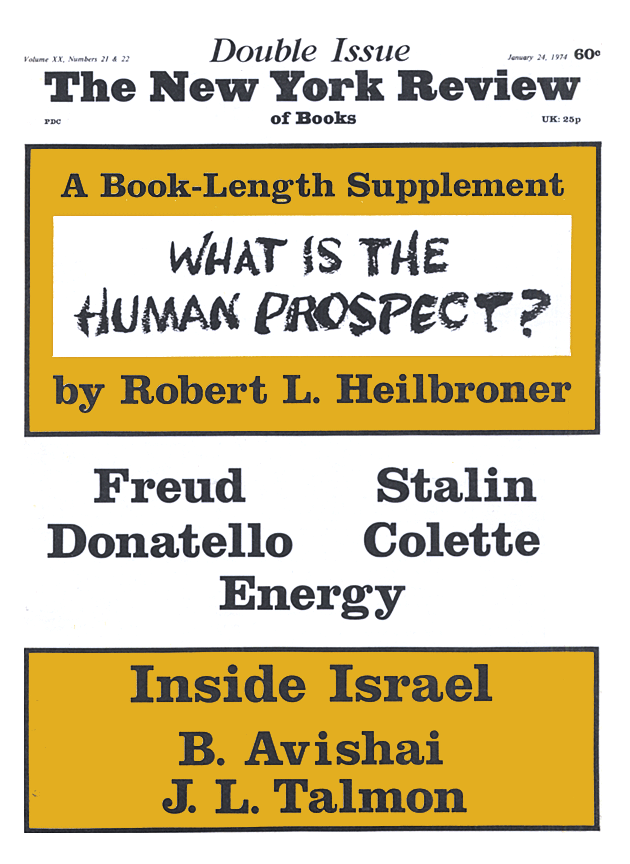

This Issue

January 24, 1974