No bouquet of letters by Alice Toklas could fail the reader; she was such a vivid character, vivid and voluble. So voluble indeed that after thirty-eight years with Gertrude Stein, for Toklas a time of relative reticence, during the next twenty she fulfilled herself in words, both spoken words and epistolary, to a degree hardly less than Stein herself had done.

She gave out published articles and three books, two on cooking and one a memoir. But what she wrote for print she wrote for money; naturally it does not vibrate like her letters. These, virtually identical with talk, could fill volumes and no doubt will. Especially if some active scholar should one day trace down all the stories, plots, and intrigues that with their dramatis personae make up the content.

The present assemblage begins on the day of Miss Stein’s death, July 27, 1946. The loss, voluntary destruction, and general nonavailability of Miss Toklas’s earlier correspondence with California family and friends, as well as the meagerness, during their years together, of her communications with Gertrude’s particular associates, seem to have made those last years alone the best field for a first coverage. During that time she poured out her voice to friends, enemies, tradesmen, lawyers, agents, and publishers with virtually no withholding of facts and no more distortion of them than might be expected from a lady whose private life had become a matter of public interest.

The theme of that later life was responsible widowhood. Though never reconciled to Gertrude’s death, she accepted the fact of it and undertook at once its sacred duties. These comprised the getting into print of Gertrude’s unpublished writings (eventually eight volumes), the advancement of her literary fame, and the preservation of her picture collection.

The publication, aided at the Yale University Press by Thornton Wilder and Donald Gallup, editorially by Carl Van Vechten, was subsidized through the sale of all her Picasso drawings, pornographic and other. The post-humous fame was encouraged by Alice’s praise or discouragement of authors wishing to write about Miss Stein. Her usual tactic was to be difficult of access, then less difficult, then to broadcast through visitors and correspondents her blessing on the essay or her distaste for it. Donald Sutherland’s Gertrude Stein: A Biography of Her Work (Yale, 1951) received and continued to receive her highest hymning. When This You See Remember Me: Gertrude Stein in Person by W. G. Rogers (Rinehart, 1948), though it brought minor scoldings, was warmly welcomed. John Malcolm Brinnin’s The Third Rose: Gertrude Stein and Her World (Little, Brown, 1959) she tended to disapprove, though she was aware of its favorable influence. On the other hand, Elizabeth Sprigge’s Gertrude Stein, Her Life and Work (Harper and Brothers, 1957) she never forgave. She did not specify her objections, but her scorn was intense. And she continued for years to speak of its author in a tone of invective generally reserved for Ernest Hemingway, whom she hated as one can only hate people to whom one has been unjust.

Alice’s love and dislikes, as a matter of fact, she did not deign to argue; she would declare them in a ukase, backing this up, if at all, by stories of kind attentions or by denigrating remarks. And I do not imagine that either her highly emotional attacks on people or her gushing approval of them actually influenced Gertrude’s fame as a writer. This was rising when she died, and it continued to rise, Alice serving chiefly as rooter for the home team, out for victory every day or, if that failed, to fire a manager, kill an umpire.

With Leon Katz, a scholar who had achieved access at Yale to the early fiction (scandalous for its time, every piece of it) and to the diary-like notebooks which Gertrude had kept from 1902 to 1911, she was in the end cooperative, so eager was she to get a look at the notebooks whose very existence she had not known. When she also expressed hope that they not be published right away Katz reassured her. Actually her examination by him and of them took place more than twenty years ago, and still their annotated version has not appeared. The deal struck was simple and fair. Alice was to answer all questions in return for being shown the transcript (the books themselves being still at Yale). Her only demurrer was that she need not volunteer information not directly asked for. In this way Alice learned what Gertrude had been doing and thinking for the five years preceding her own arrival (1907) and for the four that followed. And Katz became the world expert on Gertrude’s life and work, at least through 1911, the year she wrote Tender Buttons.

Alice’s dream of keeping the picture collection intact produced the poverty which dominated her last years and to which, had not friends formed a small committee for keeping her alive and for struggling with three batteries of lawyers—American, French-American, and French—our heroine might well have succumbed—old, bed-ridden, and blind—to despair if not outright starvation.

Advertisement

Alice had been left for her lifetime Gertrude’s income from all sources, plus the right to dispose of properties as she saw fit, including the pictures. But her reluctance to grant the eventual heirs (Gertrude’s brother Michael’s three grandchildren) any control over her possible dissipation of their fortune produced some lack of confidence. And on her side, distrust of the guardians grew into such bad will that war became inevitable and continuous; no peace-making effort on either side provoked any act of generosity. Or of justice either, since Alice, when several million dollars in picture-capital had been sequestered, could not even pay her char; and the heirs themselves, with Alice surviving, had to wait more than twenty years before touching any part of that capital. Alice, about the pictures, had been tactless, probably illegal; but neither was I aware at any time, following the affair closely, of a single one of the estate lawyers being anything but dilatory, secretive, and obstructionist.

Had Alice, after selling off drawings to pay the Yale Press, continued to raid the collection, even for her own comfort (which had certainly been Gertrude’s wish), then, should the heirs have come to protest, bargained with them toward anticipating a settlement, it is possible all parties might have benefited. And certainly Alice’s treatment of the heirs’ parents, Allan Stein and his wife Roubina, though in the early years of her usufruct this had been courteous enough, left open later very few possibilities of arrangement. In no circumstance would she countenance any sale from the collection for their benefit, though at least once she secretly disposed of a minor Picasso for her own.

All that is part of a story which eventually, I presume, will be fairly told. In these letters we hear it only through Alice’s plaints. Nor do we sense it even then with amplitude. In fact, it has not been the practice of the present editor to annotate the sorrows or the accusations in a way to make them convincing, beyond the basic facts of the bereavement and of the survivor’s faith in her loved one’s genius. These come through; everything else is suspect, on account of Alice’s penchant for excessive statement, whether of thanks, praise, or distrust.

Did Alice really “like” Thornton Wilder, for instance? I doubt it. She was grateful to him; he had been useful to Gertrude in Chicago and regarding Yale. But he kept putting off writing a preface for Four in America; it had to be insisted on and wangled for. She confessed to Mildred Rogers that he “has such a seeing eye and then what he doesn’t see he has felt and the combination has always made me a little afraid of him.” But how she butters Wilder’s sister! With unctuous compliments for the two of them and constantly little recipes, homefolks recipes involving short cuts, substitutes, and easy ways out. These are not, as cuisine, serious; nor are in general those she sent to Mildred Rogers and some others. To a publisher’s wife she did tell how to make hollow fried potatoes (the round ones, not the flat pommes soufflées), but unless I am quite wrong about those deep-butter delights she forgot to say that they require clarified butter.

When agitating for another sacred assignment, which was the liberation of a French friend convicted of wartime collaboration, she could be devoted without letup. But I have no evidence, in the letters or elsewhere, that she was of help, even though the final solution of his plight was favorable. Since I was involved myself in certain efforts toward improving the situation of this friend (for a longer time mine than Gertrude’s) it may be of interest to show here through my own correspondence a fuller picture.

In an undated letter from the fall of 1946, written the day after his condemnation, she wonders, “Is it the moment for the intervention of…?” and suggests another possible course of action.

Twice during December she wrote me again about the case. On December 28, 1946, “There has been no news of your friend—but it is neither surprising nor discouraging. There is—it would appear—more danger in appealing the case than the lawyer is ready to risk—but there are several other things to do and any one is possible to succeed if it can be pushed far enough.”

After a devoted friend of the victim had consulted Washington concerning possible pressures from there, I wrote to Alice that the American government seemed at that moment not inclined to ask of France favors for “a minor collaborator.”

Advertisement

This tactless phrase drew anger; on January 25, 1947, she wrote:

I was aghast at your attitude to[–––] and the verdict. You haven’t lived in France lately or you couldn’t feel as you do—only[–––’s] personal enemies believe him capable of such crime as you believe he committed. And we know with what positive pleasure he collected enemies. No—you have some Frenchmen on your side but they were always his personal enemies—or the French who passed the Occupation in New York possibly. Please do not ever let us speak of it again. My memory is not as good as it was so all this won’t trouble me as long as it would have in the old days. Didn’t you once quote Madame Langlois—“How astonishing that such a corrupt person [‘un garçon aussi corrompu’ had been her phrase] should write such pure music.” I’m sure the music for The Mother of Us All [at that moment about to be completed for a spring premiere] is pure if you want it to be pure and that it is intriguing, vital, and beautiful. For your music I will make any confession of faith you want—but for what it is surrounded by—Dieu m’en garde. What do you nourish it on? You may well answer that you are not a pelican of course. I don’t agree with Madame Langlois’ mot. It’s not the corruption that puts me off—it’s the being mistaken. You see so clearly in your music. Perhaps the rest of us see any thing clearly because we haven’t your gift. Let it go at that.

Would you for Gertrude’s sake not mention [–––’s] name to a living soul until his situation has changed. I could under that condition easily be

as ever

Alice

To this invigorating explosion I replied that she might as well keep her shirt on; I was not quarreling with her, nor resigning from a situation that might possibly still be helped out.

Following that, she wrote warmly on April 20 and May 9. On July 2, “About your not coming over I’m more disappointed than I can say.” Then, as a postscript, “Should you hear any rumors that Gertrude and I were Christian Scientists please deny them.”

I did not answer the request, knowing full well that the fact was true of Alice, though not of Gertrude. I did not, however, either spread such a rumor or have occasion to deny it; and I never spoke to Alice about the matter, even when we discussed later her having become a Catholic.

Neither did we ever again have sharp words. Her outburst and my reply seem to have relieved a hidden tension that had been there between us since first we met, in 1926. And sometime in the 1950s (I cannot find the letter at this time) she wrote me a declaration of faith and friendship, amende honorable complete.

Actually our correspondence went on year in year out, as did our meetings; and it is full of references to her friends, to my friends, to all the people she liked and disliked most. These letters are plenty indiscreet, sometimes malicious or outlandishly overstated. Printing them out of context, with no framework of notes to make them seem less cruel, makes Alice appear as even more irresponsible of tongue than she was and the book’s editor as perhaps willfully disobliging toward her victims.

For instance, the wife of a certain painter is dismissed as “poisonous”; in a later mention she is “admirable, competent, devoted.” Was the slap worth printing? Alice was in fact not at all a poor judge of character, but her pen was hasty.

She could also misstate facts when Gertrude’s interests or her own were involved. In the latter case she could be treacherous, lay plans, eliminate from Gertrude’s life intimates whose closeness had reached a danger point. This procedure had been operated, I am sure, regarding Gertrude’s brother Leo and also Mabel Dodge Luhan. I know that it explains the break with Ernest Hemingway, and I actually saw it used on the young French poet Georges Hugnet.

In all these cases, while ostensibly moving “to protect Gertrude,” Alice was also protecting her own monopoly of Gertrude’s sentimental life. Whether Gertrude saw through the maneuvers, actually knew when plotting was afoot, I seriously doubt. Alice could so easily make it appear that some good friend’s loyalty was being withdrawn; and Gertrude would then feel rejected, hopeless about going on, henceforth reliant only on Alice’s affection. Later she might have regretted the lost friend had not Alice covered every mention with character smears and with scorn. In no case was any reason for the break or for its permanence ever stated; even Gertrude came to pretend that with Leo and with Hemingway the intimacy had just “withered away.” Hemingway at least knew better, and that Alice, not Gertrude, was the enemy.

There were also minor excommunications, but for any of these there was usually an admissible reason. The four major ones, however, follow a pattern—an amorous attachment on Gertrude’s part (yes, even possibly to her brother), a separation without stated reasons, then, largely on Alice’s part, a campaign of frightfulness, of scurrility, and a blank wall against all attempts to research the relationship. Probably Mabel Dodge and for certain Hemingway (he said so) found Gertrude desirable. Hugnet, who did not, was amazed, in an intellectual friendship, at the quasi-love letters she would write him. Leo’s thoughts I know not.

It would be interesting to learn regarding Alice’s autos-da-fé how the victims felt. Hemingway told all in a well-known letter to William G. Rogers. Hugnet’s adventure I knew as it occurred. For him there was nothing traumatic; he took it for a plain quarrel between gens de lettres about prestige. And along with real disappointment he got sizable rewards—a Stein-language version of his long poem Enfances, published in 1930 on parallel pages in Pagany, later independently as Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded, and a hundred or more letters in Gertrude’s warmly spontaneous French, which he sold not long ago quite profitably “to an American university.”

I know only too well how harshly Alice spoke of the heirs, the disdain she felt for their parents and for their legal guardian. She tells in a letter of the present collection how she refused their mother’s request for financial aid through sale of a picture by pointing out that she didn’t have to “keep a car.” Their lack of regard for her was evident when Alice, in spite of her lawyers’ efforts and of the friendly succor organized by Doda Conrad, became increasingly in need of ready cash to pay indispensable helpers. One of these was owed at Alice’s death wages covering several years. But while Alice complained of her opponents constantly, they kept a civil silence. And waited.

Their waiting was rewarded, as was Alice’s determination to keep intact the collection, since the final price paid by a group of American investors, trustees of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, was said to be, for the main items, $6,500,000; and the pictures finally were shown together, along with some that had belonged to Gertrude’s brothers, at that museum. Indeed, they seem not yet to have come on the open market.

Aside from this partial victory, due as much to the stubbornness of the heirs in trust and to her own estate lawyers as to any effort of hers, Alice Toklas’s more than twenty years of “staying on alone” chalked up no major success, merely gratifications. Publication of the remaining works, ordered in Gertrude’s will, could scarcely have been omitted. Likewise, Gertrude’s literary fame would have grown, as it has in fact gone on growing, even with Alice no longer tending it. Her efforts at procuring the liberation of the alleged collaborator were quite without effect. His own poor health in prison, compassionate transfer to a hospital, escape from there at his own risk and expense, a belated presidential pardon brought about through his brother’s persistence and tolerated by his political enemies (themselves too grown compassionate after a shamefully skimpy trial and an admittedly improper sentence), these saved his life and brought him liberty. As a scholar he has taught successfully since in Spain and Switzerland, written new books and published them in France. His rehabilitation and return, I may add, gratified not only Alice.

She was happy also with the success of Gertrude’s posthumous opera The Mother of Us All and the revival of Four Saints in Three Acts, which she saw in Paris. And she never failed to express delight with books by people she approved, though I must say her tastes were peculiar. She considered Mercedes de Acosta’s memoir Here Lies the Heart a “tremendous accomplishment,” a “new volume” of James Joyce’s letters “incredibly woefully ignorant uneducated and blastingly uncultivated.”

Alice Toklas herself was none of those. For good or ill, she was a lady. She knew the household arts, was adept at hospitality, could in a most accomplished manner both read and write. Her expertness in all such ways, plus volubility and wit, made her a delicious companion. And her utter devotion to Gertrude Stein gave her detachment in other relationships, justifying any walk-out, any lie or treachery or plotting. I am not sure she did not practice on occasion unfriendly magic, just as she burned candles to Sainte Geneviève for bringing about beneficial events, long before Roman Catholicism had become her faith.

What that conversion really amounted to is hard to judge. She had been born and reared in a well-to-do skeptical family, Jewish but not Orthodox, and at twelve, to please a friend of her mother’s, was baptized a Catholic. No record of the baptism has been found, but it may have got destroyed in the Fire. Later she became a Christian Scientist, how much later I do not know; but she wrote Donald Sutherland at seventy, on October 8, 1947, “for the first time in fifty-three years I’d to see the doctor,” in other words, not since she was seventeen. Conversion from Moses to Mrs. Eddy is common, from Science to Holy Church very rare. In 1957 the need felt must have been very great for Alice Toklas, at eighty, to make her First Communion. (An American priest had credited her California baptism.)

Admittedly the transfer of faith had been motivated by a desire (self-centered of course) for reunion with her great and beloved Gertrude, whom God, she believed, could not possibly have failed to receive. She writes after this of praying for people, and surely she made some gifts of money to her priest. But no lessening of her propensities to scorn, malice, anger, even gluttony, appeared. By nature a spendthrift and a showy one, she entertained at only the most expensive restaurants, giving hundred-dollar tips plus the fifteen percent already charged. One wonders whether some of this throwing-away was not perhaps a getting even with the heirs, and whether they were not perhaps quite wise in withholding her access to unlimited cash. Also whether, had they not done this, she might eventually have made substantial church gifts out of money they considered rightfully theirs.

With even urgent expenditures prevented, Alice’s friends saw to it that to the end she had a roof, a maid, medical care, and for food a few necessary luxuries. Also to the end, impotent, incontinent, and almost blind, she thanked them, as a lady should, in warmest terms, restating in every letter her affection, offering her prayers, adding dirty cracks about the young Steins and about Ernest Hemingway, still unforgiven, though dead.

What curses she might have launched against the present volume I can only guess, considering its casual tone, and also how she had always fought with editors, even the best. I must say I am shocked myself at the absence throughout the book of the three dots that acknowledge an omission, though several of the recipients have assured me that their letters have been generously cut. Such punctilio might have made perusal more difficult; but it is the custom, and neglecting it is unfair to both writer and reader. So is an incomplete index. Actually the letters as printed tell no consistent story, however close a portrait they may give of the Toklas daily life, her tempers, her temperament, her sorrows and happy times. What access there had been to a fuller and fairer story I cannot judge. My own two hundred or more communications were not seen, since my initial reluctance toward entrusting these led to no further inquiries. Other sources may have been similarly hesitant. But Alice’s tirades and massive indiscretions do invite some reserve.

Among the book’s unimportant errata that I have noted, here are a baker’s dozen:

- To Picasso’s “bateau lavoir” studio, where he painted Gertrude Stein’s portrait, there is no “nearby Seine,” the rue Ravignan, near the top of Montmartre, being at least two miles away. (P. 16)

- Picasso arrived in Paris in 1900, not 1903. (P. 16)

- Elliot Paul, though often a contributor to The Chicago Tribune and occasionally to The New York Herald (their Paris editions), was never the editor of either. (P. 51)

-

Toklas’s miscalling the office des changes an office d’echange needs correcting. (P. 73)

-

Georges Maratier’s American friend was Ed Livengood (not Livergood). (P. 76)

-

The statement that at a reading of Picasso’s play “Georges Hugnet supplied the music” needs further explanation, since this excellent poet was no musician at all. (P. 115)

-

Le Colombier (not Columbier) was the name of the house near Culoz. (P. 136)

-

Angel Regus (for Reyes) is no doubt an unchecked misreading of Alice’s penmanship, as Aaron Copeland (for Copland) might be anyone’s mistake, surprising though it is. (P. 172)

-

Paul Bowles knew Stein and Toklas from 1931, not 1935. (P. 189)

-

Opaline bowls, surely, not opalier. (P. 190)

-

Lunch at Le Bossu, yes, not Le Bosse. (P. 205)

-

The Mallorcan twisted coffee-cake is an ensaimada (not ensimada). (P. 214)

-

Former head of the Vassar Art Department was Agnes Rindge (not Range). (P. 238)

None of these slips is grave, though they all indicate negligence about checking dates, proper names, and foreign-language references. In general the book, though handsomely printed on good stock with surfaces hard enough for reproducing photographs, is editorially not quite first-class, in spite of prefatorial credits to Donald Gallup (in charge of Yale’s Gertrude Stein Collection) and Leon Katz (editor of Stein’s notebooks). Nevertheless the book is a joy because Toklas the woman was for real—gushy, gossipy, grudge-holding, and unforgiving, but also generous, warm, lively, perspicacious, vastly sociable, and civilized in the Victorian, the Edwardian, the pre-World War I way, which is the good way or, as she would have put it, the San Francisco way.

I do hope she has made it to Heaven and is no longer alone but finally with Gertrude forever, though in spite of all her social charms, she might become a nuisance there if she went in for “protecting” her friend. And dear Gertrude would be happy to have her there, certainly for the housekeeping, but most of all for help in analyzing character and in remembering exactly who everybody is and how to put them into stories that can be repeated throughout eternity in exactly the way that they will have finally come to be told by them to each other.

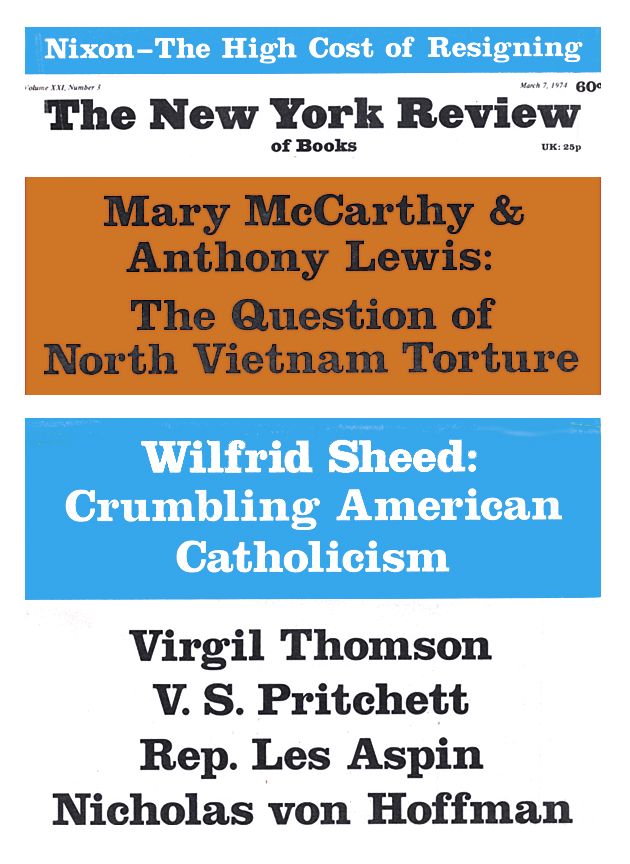

This Issue

March 7, 1974