In the preface to his novel Le Bleu du ciel,1 Georges Bataille makes an important distinction between books that are written for the sake of experiment and books that are born of necessity. Bataille argues that the books that mean most to us are usually those which ran counter to the idea of literature that prevailed at the time they were written. He speaks of “a moment of rage” as the kindling spark of all great works: it cannot be summoned by an act of will, and its source is always extraliterary. Self-conscious experimentation is generally the result of a real longing to break down the barriers of literary convention. But most avant-garde works do not survive; in spite of themselves, they remain prisoners of the very conventions they try to destroy. The poetry of Futurism, for example, which made such a commotion in its day, is read by hardly anyone now except scholars and historians of the period.

On the other hand, certain writers who played little or no part in the literary life around them—Kafka, for example—have gradually come to be recognized as essential. The work that changes our sense of literature, that gives us a new feeling for what literature can be, is the work that in some way changes our lives. It often seems improbable, as if it had come from nowhere, and because it stands so ruthlessly outside the norm we have no choice but to create a new place for it.

Le Schizo et les langues is not only improbable, but totally unlike anything that has come before it. To say that it is a work written in the margins of literature is not enough: its place, properly speaking, is in the margins of language itself. Written in French by an American, it has little meaning unless it is considered an American book; and yet, for reasons that will be made clear, it is also a book that excludes all possibility of translation. It hovers somewhere in the limbo between the two languages, and nothing will ever be able to rescue it from this precarious existence. For what we are presented with here is not simply the case of a writer who has chosen to write in a foreign language. The author of this book has written in French precisely because he had no choice. It is the result of brute necessity, and the book itself has the urgency of an act of survival.

Louis Wolfson is a schizophrenic. He was born in 1931 and lives in New York. For want of a better description, I would call his book a kind of third-person autobiography, a memoir of the present, in which he records the facts of his disease and the utterly bizarre method he has devised for dealing with it. Referring to himself as “the schizophrenic student of languages,” “the mentally ill student,” “the demented student of idioms,” Wolfson uses a narrative style that partakes of both the dryness of a clinical report and the inventiveness of fiction. Nowhere in the text is there even the slightest trace of delirium or “madness”: every passage is lucid, forthright, and uncannily objective. As we read along, wandering through the labyrinth of the author’s obsessions, we come to feel with him, to identify with him, in the same way we identify with the eccentricities and torments of Kirilov, or Molloy.

Wolfson’s problem is the English language, which has become intolerably painful to him, and which he refuses either to speak or listen to. He has been in and out of mental institutions for over ten years, steadfastly resisting all cooperation with the doctors, and now, at the time he is writing the book (the late Sixties), he is living in the cramped lower-middle-class apartment of his mother and stepfather in New York. He spends his days sitting at his desk studying foreign languages—principally French, German, Russian, and Hebrew—and protecting himself against any possible assault of English by keeping his fingers stuck in his ears, or listening to foreign language broadcasts on his transistor radio with two earplugs, or keeping a finger in one ear and an earplug in the other.

In spite of these precautions, however, there are times when he is not able to ward off the intrusion of English—when his mother, for example, bursts into his room shrieking something to him in her loud and high-pitched voice. It becomes clear, too, that he cannot drown out English by simply translating it into another language. Converting an English word into its foreign equivalent leaves the English word intact; it has not been destroyed, but only put to the side, and is still there waiting to menace him.

The system that he develops in answer to this problem is complex, but not difficult to follow once one has become familiar with it, since it is based on a consistent set of rules. Drawing on the several languages he has studied, he becomes able to transform English words and phrases into phonetic combinations of foreign letters, syllables, and words that form new linguistic entities, which not only resemble the English in meaning, but in sound as well. His descriptions of these verbal acrobatics are highly detailed, often taking up as many as ten pages, but perhaps the result of one of the simpler examples will give some idea of the process. The sentence “Don’t trip over the wire!” is changed in the following manner: “Don’t” becomes the German “Tu’ nicht,” “trip” becomes the first four letters of the French “trébucher,” “over” becomes the German “über,” “the” becomes the Hebrew “èth hè,” and “wire” becomes the German “Zwirn,” the middle three letters of which correspond to the first three letters of the English word: “Tu’ nicht tréb über èth hè Zwirn.”

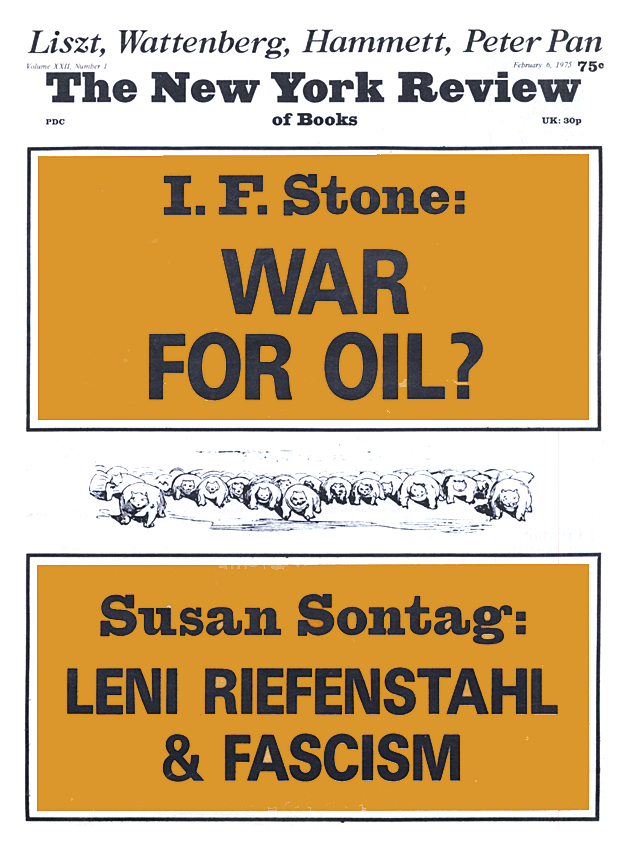

Advertisement

At the end of this passage, exhausted but gratified by his efforts, Wolfson writes: “If the schizophrenic did not experience a feeling of joy as a result of his having found, that day, these foreign words to annihilate yet another word of his mother tongue (for perhaps, in fact, he was incapable of this sentiment), he certainly felt much less miserable than usual, at least for a while.”2

The book, however, is far more than just a catalogue of these transformations. They are at the core of the work, and in some sense define its purpose, but the real substance is elsewhere, in the human situation and daily life that envelop Wolfson’s preoccupation with language. Few other books give a more immediate feeling of what it is like to live in New York and to wander through the streets of the city. Wolfson’s eye for detail is excruciatingly precise, and each nuance of his observations—whether it be the prison-like atmosphere of the Forty-second Street Public Library reading room, the anxieties of a high school dance, the Times Square prostitute scene, or a conversation with his father on a bench in a city park—is rendered with attentiveness and authority A tendency to detach himself from his own experience is continually at work, and the prose, which opens this distance, at the same time acts as a kind of lure, always drawing us toward what is written.

By treating himself in the third person, Wolfson is able to create a space between himself and himself, and thereby make himself visible, to watch himself, to prove to himself that he exists. The French language serves much the same function. By looking out on his world through a different lens, by punning his world—which is immured in English—into a different language, he is able to see it with new eyes, in a way that is less oppressive to him, as if, to some slight degree, he were able to have an effect upon it.

In his toneless, deadpan style, he manages to present a portrait of life among the Jewish poor that is so horrendously comical and vivid that it stands comparison with the early childhood passages of Céline’s Death on the Installment Plan. There seems to be no question that Wolfson knows what he is doing. His aims are not aesthetic ones, but in his patient determination to record everything, to set down the facts as accurately as possible, he has exposed the true absurdity of his situation, which he is often able to respond to with an ironical sense of detachment and whimsy.

His parents were divorced when he was four or five years old. His father has spent most of his life, on the periphery of the world, without work, living in cheap hotels, idling away his time in cafeterias smoking cigars. He claims that his marriage took place “with a cat in the bag,” since it was not until later that he learned his wife had a glass eye. When she eventually remarried, her second husband, now Wolfson’s stepfather, disappeared after the wedding with her diamond ring—only to be tracked down by her and thrown into jail the moment he stepped off a plane a thousand miles away. His release was granted only on the condition that he go back to his wife.

The mother is the dominant, suffocating presence of the book, and when Wolfson speaks of his “langue mater-nellie” it is clear that his abhorrence of English is in direct function to his abhorrence of his mother. She is a grotesque character, a monster of vulgarity, who ridicules her son’s language studies, insists on speaking to him in English, and perseveres in doing exactly the opposite of what would make his life bearable. She spends much of her spare time playing popular songs on an electric organ, with the volume turned up full blast. Sitting over his books, his fingers stuck in his ears, the student sees the lampshade on his desk begin to rattle, feels the whole room vibrate in rhythm to the piece, and as the deafening music penetrates him, he automatically thinks of the English lyrics of the songs, which drives him into a fury of despair. (Half a chapter is devoted to his linguistic transformation of the words to “Good Night, Ladies.”)

Advertisement

But Wolfson never really judges her. He only describes. And if he allows himself an occasional smirk of under-statement, it would seem to be his right. “Naturally, her optical weakness seemed in no way to interfere with the capacity of her speech organs (perhaps it was even the reverse), and she would speak, at least for the most part, in a very high and very shrill voice, even though she was positively able to whisper over the telephone when she wanted to arrange secretly for her son’s entrance into the psychiatric hospital, that is to say, without his knowledge.”3

Beyond the constant threat of English posed by his mother (who is the very embodiment of the language for him), the student suffers from her in her role as provider. Throughout the book, his linguistic activities are counterpointed by his obsessions with food, eating, and the possible contamination of his food. He oscillates between a violent disgust at the thought of eating, as if it were a basic contradiction of his language work, and terrifying orgies of gluttony that leave him sick for hours afterward.

Each time he enters the kitchen, he arms himself with a foreign book, repeats aloud certain foreign phrases he has been memorizing, and forces himself to avoid reading the English labels on the packages and cans of food. Reciting one of the phrases over and over again, like a magical incantation to keep away evil spirits, he tears open the first package that comes to hand—containing the food that is easiest to eat, which is usually the least nutritional—and begins to stuff the food into his mouth, all the while making sure that it does not touch his lips, which he feels must be infested with the eggs and larvae of parasites. After such bouts, he is filled with self-recrimination and guilt. As Gilles Deleuze suggests in his preface to the book, “His guilt is no less great when he has eaten than when he has heard his mother speak. It is the same guilt.”4

This is the point, I feel, at which Wolfson’s private nightmare touches on certain larger questions about language. There is a fundamental connection between speaking and eating, and by the very excessiveness of Wolfson’s experience we are able to see how deep this relationship is. Speech is an anomaly, a biologically secondary function of the mouth, and myths about language are often linked to the idea of food. Adam is granted the power of naming the creatures of Paradise and is later expelled for having eaten of the Tree of Knowledge. Mystics fast in order to prepare themselves to receive the word of God. The body of Christ, the word made flesh, is eaten in holy communion. It is as if the life-serving function of the mouth, its role in eating, had been transferred to speech, for it is language that creates us and defines us as human beings. Wolfson’s fear of eating, the guilt he feels over his escapades of self-indulgence; are an acknowledgment of his betrayal of the task he has set for himself: that of discovering a language he can live with. To eat is to compromise, since it sustains him within an already discredited and unacceptable world.

Wolfson seems to have undertaken his search in the hope of one day being able to speak English again—a hope that flickers now and then through the pages of the book. The invention of his system of transformations, the writing of the book itself, are part of a slow progression beyond the hermetic agony of his disease. By refusing to allow anyone to impose a cure on him, by forcing himself to confront his own problems, to live through them alone, he senses in himself a dawning awareness of the possibility of living among others—of being able to break free from his one-man language and enter a language of men.

The book he has created from this struggle is difficult to define, but it should not be dismissed as a therapeutic exercise, as yet another document of mental illness to be filed on the shelves of medical libraries. Gallimard, it seems to me, has made a serious error in bringing out Le Schizo et les langues as part of a series on psychoanalysis. By giving the book a label, they have somehow tried to tame the rebellion that gives the book its extraordinary force, to soften “the moment of rage” that everywhere informs Wolfson’s writing.

On the other hand, even if we avoid the trap of considering this work as nothing more than a case history, we should still hesitate to judge it by established literary standards and to look for parallels with other literary works. Wolfson’s method, in some sense, does resemble the elaborate word-play in Finnegans Wake and in the novels of Raymond Roussel, but to insist on this resemblance would be to miss the point of the book. Louis Wolfson stands outside literature as we know it, and to do him justice we must read him on his own terms. For it is only in this way that we will be able to discover his book for what it is: one of those rare works that can change our perception of the world.

This Issue

February 6, 1975

-

1

Le Bleu du ciel, 1957. In Oeuvres Complètes de Georges Bataille, Vol. III (Gallimard, 1971), p. 381. ↩

-

2

Le Schizo et les langues, p. 213. The French reads: “Si le schizophrène n’éprouvait pas de joie comme résultat de ses trouvailles, ce jour-là, de mots étrangers pour anéantir un mot de plus de sa langue maternelle (car peut-être était-il plutôt incapable de ce sentiment), assurément il se sentait beaucoup moins misérable que d’habitude, ceci du moins durant un peu de temps.” ↩

-

3

Le Schizo et les langues, p. 31. The French reads: “Naturellement, sa faiblesse optique ne semblait aucunement interférer avec la capacité de ses organes de parole (peut-être même c’était le contraire), et elle parlait, du moins pour la plupart, d’une voix très haute et très aiguë, bien qu’elle pût vraiment chuchoter au téléphone quand elle voulait clandestinement arranger l’admission de son fils à l’hôpital psychiatrique, c’est-à-dire à son insu.” ↩

-

4

Le Schizo et les langues, p. 12. ↩