I believe those who describe him didn’t know him as I did, and here’s why. First, I could know only one side of his being—the radiant side. After all I was just a stranger, probably a not easily understood twenty-year-old woman, a foreigner. Secondly, I myself noticed a big change in him when we met in 1911. Somehow, he had grown dark and haggard.

In 1910 I saw him extremely seldom: only a few times. Nevertheless he wrote to me all winter long.1 He didn’t tell me that he composed verses.

As I understand it now, what he must have found astonishing in me was my ability to guess rightly his thoughts, to know his dreams and other small things—others who knew me had become accustomed to this a long time before. He kept repeating: “On communique.” Often he said: “Il n’y a que vous pour réaliser cela.”

Probably, we both did not understand one important thing: everything that happened was for both of us a prehistory of our future lives: his very short one, my very long one. The breathing of art still had not charred or transformed the two existences; this must have been the light, radiant hour before dawn.

But the future, which as we know throws its shadow long before it enters, knocked at the window, hid itself behind lanterns, crossed dreams, and frightened us with horrible Baudelairean Paris, which concealed itself someplace near by.

And everything divine in Modigliani only sparkled through a kind of darkness. He was different from any other person in the world. His voice somehow always remained in my memory. I knew him as a beggar and it was impossible to understand how he existed—as an artist he didn’t have a shadow of recognition.

At that time (1911) he lived at Impasse Falguière. He was so poor that when we sat in the Luxembourg Gardens we always sat on the bench, not on the paid chairs, as was the custom. On the whole he did not complain, not about his completely evident indigence, nor about his equally evident nonrecognition.

Only once in 1911 did he say that during the last winter he felt so bad that he couldn’t even think about the thing most precious to him.

He seemed to me encircled with a dense ring of loneliness. I don’t remember him exchanging greetings in the Luxembourg Gardens or in the Latin Quarter where everybody more or less knows each other. I never heard him tell a joke. I never saw him drunk nor did I smell wine on him. Apparently, he started to drink later, but hashish already somehow figured in his stories. He didn’t seem to have a special girl friend at that time. He never told stories about previous romances (as, alas, everybody does). With me he didn’t talk about anything that was worldly. He was courteous, but this wasn’t a result of his upbringing but the result of his elevated spirit.

At that time he was occupied with sculpture; he worked in a little courtyard near his studio. One heard the knock of his small hammer in a deserted blind alley. The walls of his studio were hung with portraits of fantastic length (as it seems to me now—from the floor to the ceiling). I never saw their reproductions—did they survive? He called his sculpture “la chose“—it was exhibited, I believe, at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911. He asked me to look at it, but did not approach me at the exhibition, because I was not alone, but with friends. During my great losses, a photograph of this work, which he gave to me, disappeared also.

At this time Modigliani was crazy about Egypt. He took me to the Louvre to look at the Egyptian section; he assured me that everything else, “tout le reste,” didn’t deserve any attention. He drew my head in the attire of Egyptian queens and dancers, and he seemed completely carried away by the great Egyptian art. Obviously Egypt was his last passion. Very soon after that he became so original that looking at his canvases you didn’t care to remember anything. This period of Modigliani’s is now called la période nègre.

* * *

He used to say: “les bijoux doivent être sauvages” (in regard to my African beads), and he would draw me with them on.

He led me to look at le vieux Paris derrière le Panthéon at night, by moonlight. He knew the city well, but still we lost our way once. He said: “J’ai oublié qu’il y a une île au milieu [l’île St-Louis].” It was he who showed me the real Paris.

Of the Venus of Milo he said that the beautifully built women who are worth being sculptured and painted always look awkward in dresses.

Advertisement

When it was drizzling (it very often rains in Paris), Modigliani walked with an enormous and very old black umbrella. We sat sometimes under this umbrella on the bench in the Luxembourg Gardens. There was a warm summer rain; nearby dozed le vieux palais à l’italien, while we in two voices recited from Verlaine, whom we knew well by heart, and we rejoiced that we both remembered the same work of his.

I have read in some American monograph that Beatrice X may have exerted a big influence upon Modigliani—she is the one who called him “perle et pourceau.” I can testify, and I consider it necessary that I do so, that Modigliani was exactly the same enlightened man long before his acquaintance with Beatrice X—that is, in 1910. And a lady who calls a great painter a suckling pig can hardly enlighten anyone.

People who were older than we were would point out on which avenue of the Luxembourg Gardens Verlaine used to walk—with a crowd of admirers—when he went from “his café,” where he made orations every day, to “his restaurant” to dine. But in 1911 it was not Verlaine going along this avenue, but a tall gentleman in an impeccable frock coat wearing a top hat, with a Legion of Honor ribbon—and the neighbors whispered: “Henri de Régnier.” This name meant nothing to us. Modigliani didn’t want to hear about Anatole France (nor, incidentally, did other enlightened Parisians). He was glad that I didn’t like him either. As for Verlaine he existed in the Luxembourg Gardens only in the form of a monument which was unveiled in the same year. Yes. About Hugo, Modigliani said simply: “Mais Hugo c’est déclamatoire.”

* * *

One day there was a misunderstanding about our appointment and when I called for Modigliani, I found him out—but I decided to wait for him for a few minutes. I held an armful of red roses. The window, which was above the locked gates of the studio, was open. To while away the time, I started to throw the flowers into the studio. Modigliani didn’t come and I left.

When I met him, he expressed his surprise about my getting into the locked room while he had the key. I explained how it happened. “It’s impossible—they lay so beautifully.”

Modigliani liked to wander about Paris at night and often when I heard his steps in the sleepy silence of the streets, I came to the window and through the blinds watched his shadow, which lingered under my windows….

The Paris of that time was already in the early Twenties being called “vieux Paris et Paris d’avant guerre.” Fiacres still flourished in great numbers. The coachmen had their taverns, which were called “Rendez-vous des cochers.” My young contemporaries were still alive—shortly afterward they were killed on the Marne and at Verdun. All the left-wing artists, except Modigliani, were called up. Picasso was as famous then as he is now, but then the people said: “Picasso and Braque.” Ida Rubinstein acted Salome. Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe grew to become a cultural tradition (Stravinsky, Nijinsky, Pavlova, Karsavina, Bakst).

We now know that Stravinsky’s destiny also didn’t remain chained to the 1910s, that his work became the highest expression of the twentieth century’s spirit. We didn’t know this then. On June 20, 1911, The Firebird was produced. Petrushka was staged by Fokine for Diaghilev on July 13, 1911.

The building of the new boulevards on the living body of Paris (which was described by Zola) was not yet completely finished (Boulevard Raspail). In the Taverne de Panthéon, Verner, who was Edison’s friend, showed me two tables and told me: “These are your social-democrats, here Bolsheviks and there Mensheviks.” With varying success women sometimes tried to wear trousers (jupes-culottes), sometimes they almost swaddled their legs (jupes entravées). Verse was in complete desolation at that time, and poems were purchased only because of vignettes which were done by more or less well known painters. At that time, I already understood that Parisian painting was devouring French poetry.

René Gille preached “scientific poetry” and his so-called pupils visited their maître with a very great reluctance. The Catholic church canonized Jeanne d’Arc.

Où est Jeanne la bonne Lorraine

Qu’Anglais brulèrent à Rouen?

(Villon)

I remembered these lines of the immortal ballad when I was looking at the statuettes of the new saint. They were in very questionable taste. They started to be sold in the same shops where church plates were sold.

* * *

An Italian worker had stolen Leonardo’s Gioconda to return her to her homeland, and it seemed to me later, when I was back in Russia, that I was the last one to see her.

Advertisement

Modigliani was very sorry that he couldn’t understand my poetry. He suspected that some miracles were concealed in it, but these were only my first timid attempts. (For example in Apollo, 1911). As for the reproductions of the paintings which appeared in Apollo (“The World of Art”) Modigliani laughed openly at them.

I was surprised when Modigliani found a man, who was definitely unattractive, to be handsome. He persisted in his opinion. I was thinking then: he probably sees everything differently from the way we see things. In any case, that which in Paris was said to be in vogue, and which was described with splendid epithets, Modigliani didn’t notice at all.

He drew me not in his studio, from nature, but at his home, from memory. He gave these drawings to me—there were sixteen of them. He asked me to frame them in passe-partout and hang them in my room at Tsarskoye Selo. In the first years of revolution they perished in that house at Tsarskoye Selo. Only one survived, in which there was less presentiment of his future “nu” than in the others.

Most of all we used to talk about poetry. We both knew a great many French verses: by Verlaine, Laforgue, Mallarmé, Baudelaire.

I noticed that in general painters don’t like poetry and even somehow are afraid of it.

He never read Dante to me, possibly because at that time I didn’t yet know Italian.

Once he told me: “J’ai oublié de vous dire que je suis Juif.” That he was born in the environs of Livorno and that he was twenty-four years old he told me immediately—but at that time he really was twenty-six.

Once he told me that he was interested in aviators (nowadays we say pilots) but once, when he met one of them, he was disappointed: they turned out to be simply sportsmen (what did he expect?).

At this time light airplanes (which were—as everybody knows—like shelves) were circling around over my rusty and somewhat curved contemporary (1889) Eiffel Tower. It seemed to me to resemble a gigantic candlestick, which was lost by a giant in the middle of a city of dwarfs. But that’s something Gulliverish.

* * *

And all around raged the newly triumphant cubism, which remained alien to Modigliani.

Marc Chagall had already brought his magic Vitebsk to Paris and Charlie Chaplin—not yet a rising luminary, but an unknown young man—roamed the Parisian boulevards (“The Great Mute”—as cinematography then was called—still remained eloquently silent).

* * *

“And a great distance away in the north…” in Russia died Leo Tolstoy, Vrubel’, Vera Komissarzhevskaia; symbolists declared themselves in a state of crisis and Aleksandr Blok prophesied:

Oh, if You children only knew

About coldness and darkness

Of the days to come….

The three whales, on which the Twenties now rest—Proust, Joyce, and Kafka—didn’t yet exist as myths, though they were alive as people.

* * *

I was firmly convinced that such a man as Modigliani would start to shine, but when in coming years I asked people who came from Paris about him, the reply was always the same: we don’t know, never heard of him.2

Only once N. S. Gumilev, when we went together for the last time to see our son in Bezhetsk (in May 1918), and I mentioned the name Modigliani, called him “a drunken monster” or something of the kind. He told me that they had had a clash because Gumilev had spoken in some company in Russian; Modigliani protested this. Only about three years remained for both of them and a great posthumous fame awaited both.

Modigliani regarded travelers with disdain. He considered journeys as a substitute for real action. He always had Les chants de Maldoror in his pocket; this book at that time was a bibliographical rarity. He told me that once he went to a Russian church to the Easter matins—he went to see the religious procession with cross and banners—he liked magnificent ceremonies—and that “probably a very important gentleman” (I should think from the embassy) came up to him and kissed him three times. It seems to me Modigliani didn’t clearly understand the meaning of this.

For a long time I thought that I would never hear anything about him. But I did and quite a lot.

* * *

In the beginning of NEP,3 when I was on the board of the Writer’s Union of those days, we usually had our meetings in A. N. Tikhonov’s office.4 At that time correspondence with foreign countries began to return to normal, and Tikhonov used to receive many books and periodicals. It happened that once during the conference someone passed an issue of a French art magazine to me. I opened it—a photograph of Modigliani…. Small cross…. There was a big article—a kind of obituary—and from this article I learned that Modigliani was a great artist of the twentieth century (as I remember he was compared with Botticelli) and that there were already monographs about him in English and in Italian. Later on in the Thirties Ehrenburg, who dedicated his verses5 to Modigliani and who knew him in Paris later than I did, told me much about him. I also read about Modigliani in a book, From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter, by Carco, and in a cheap novel, whose author coupled him with Utrillo. I can say firmly that the hybrid, which is pictured in this book, does not bear any resemblance to Modigliani in 1910-1911, and that what the author did belongs to the category of the impermissible.

And even quite recently Modigliani became a hero of a pretty vulgar French film, Montparnasse 19. That’s extremely distressing!

Bol’shevo 1958-Moscow 1964

—translated by Djemma Bider

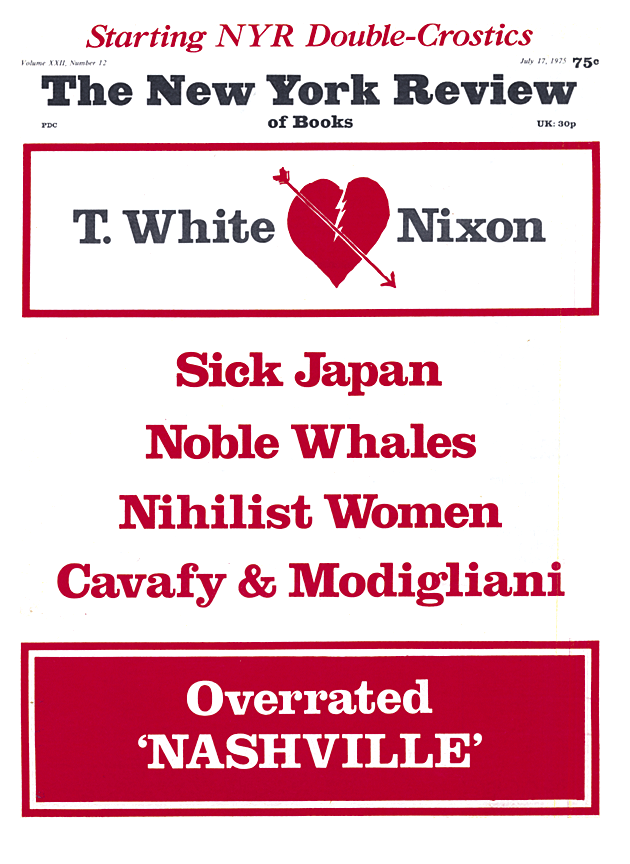

This Issue

July 17, 1975

-

1

I remember a few sentences from his letters. Here is one of them: “Vous êtes en moi comme une hantise.” ↩

-

2

He was not known to A. Ekster (the artist, from whose school came all Kiev’s left-wing artists), or to Anrep (well-known mosaic artist), or to N. Al’tman, who in the years 1914-1915 painted my portrait. ↩

-

3

The New Economic Policy. ↩

-

4

At the World Literature Publishing House, 36 Mokhovaia Street, Leningrad. ↩

-

5

They were printed in a book, The Poetry about Eves. ↩