Will Christianity survive the year 2000 as a major religion of mankind? Two generations ago such a question would have been outrageous. On the one hand, Fortress Vatican presided over by the saintly Pius X, on the other, the great missionary conference held in Edinburgh in 1910 each in its own way marked the triumphant progress of the religion of Western man. Well might the American Methodist John Raleigh Mott prophesy the evangelization of the world in a single generation. Even in 1938, on the eve of the Second World War, my predecessor as Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Glasgow, Rev. John Foster, described the missionary conference at Tamebaram in south India as one of the milestones along the road toward the Christianization of the world.

Today such ideals, and the myths that sustained them, have faded. Under the combined pressures of human disasters on an unimaginable scale, successive scientific revolutions, and the standardization and secularization of society the world over, the old certainties of the Christian faith have steadily been eroded. If the major Churches edge closer together, their movement too often resembles sheep huddling before a storm. Theirs has become unity for the sake of survival, not the alliance of advancing and optimistic creeds. The “Nadir of Triumphalism” that has succeeded the end of the Second World War is still with us.

All this is brilliantly, if somberly and sometimes even wrongheadedly, told by Paul Johnson. His is a tour de force, one of the most ambitious surveys of the history of Christianity ever attempted and perhaps the most radical. In eight sections, which show a great range of reading and a knowledge that is never made tedious, he tells the story of the rise, greatness, and decline of Christianity; how the “Mitred Lords and Crowned Ikons” of the tenth century become the “almost chosen peoples” of the Reformation era, the triumphant missionaries of the nineteenth century, only to fail within his own lifetime. Characteristically, the story opens with the Jerusalem Council of 49.

In the author’s view this, and not even Pentecost or presumably the Crucifixion, was the decisive moment in the early history of Christianity. Had the surviving followers of Jesus of Nazareth prevailed over Paul and compelled converts to Christianity to be circumcised, then the teachings of Jesus would have become nothing more than the hallmark of a Jewish sect doomed to be submerged eventually into the mainstream of the ancient creed. Paul, if he did not win, went his own way, and the fall of Jerusalem in 70 ended the prospect of an emergence of a rival Jewish-Christian faith led by the followers of Jesus’ brother, James.

Christianity, then, is primarily Paul’s interpretation of Jesus, the worship of the pre-existent son of God, whom he identified with the historical Jesus. The latter does indeed exist for the author as much as he did for Paul, though in the few pages devoted to him one may wonder why it was his resurrection that caused such a stir. Jesus was not a simple figure we are told. He may have had political connections with his cousin, John the Baptist. His actions and motives were complex, and he taught something that was hard to grasp. He had a new doctrine to deliver, namely salvation through love, sacrifice, and faith, and he presented it in the guise of a reformation of the old. His teaching was more a series of glimpses or matrices, a collection of insights, rather than a code of doctrine.

There is truth in this, but it is legitimate to ask whether this is anything like the whole truth, and how so complicated a personality would be regarded as perfect man and as God, or more intelligibly, the value of God for humanity. So grotesquely Nestorian a figure could hardly have gained the allegiance of Paul or even James. The nagging doubt whether Johnson has presented a credible portrait of the life and teaching of Jesus as told in the synoptic Gospels remains with the reader throughout. It is not easy to accept that Paul’s letter to the Romans had a greater effect on the religious history of mankind than the four Gospels.

From Paul, however, there was no looking back for the Church. The mixture of Jewish and Greek ideas that gave rise to a permanent clergy was fruitful. The episcopate provided the Christians with a greater sense of unity than any other cult possessed. The Christians, thanks largely to Origen (d. 254), were able to absorb enough Greek philosophy to make their creed attractive to intellectuals. Their conspicuous works of mercy brought in the people. Origen’s pagan contemporaries were forced on to the defensive. By the latter part of the third century, it was clear that paganism could provide no credible alternative to Christianity. Constantine’s conversion merely set the seal on a victory already won.

Advertisement

The ensuing age of the Fathers was a crucial one for the Church. In alliance with the Roman state, Christianity was the greatest single force in the world. Somehow, as at other periods of its history, it just did not succeed. Its institutions such as the papacy were contaminated by outrageous worldliness, as in the time of Pope Damasus, 366-384. Search for power rather than humility and generosity characterized the episcopate of Ambrose of Milan. From martyrs the Christians became inquisitors. Ambrose’s episcopate “marked an important stage in the construction of a society in which only orthodox Christianity exercised full civic rights.” An even more important one was demonstrated by the career of Ambrose’s younger contemporary, Augustine of Hippo. For him the author feels profound dislike tinged with respect. “Augustine was the dark genius of imperial Christianity.” His dealings with the Donatists ensured that persecution of unorthodoxy would not only be practiced but justified from Scripture. His triumph over the Pelagians snapped the tradition of speculating on first principles and criticizing accepted conclusions. He bridged the gap between the humanistic optimism of the classical world and the despondent passivity of the Middle Ages, not to the advantage of humanity.

The Renaissance and Reformation saw a decisive break from the alternatives of institutionalism and anarchic millenarianism that had characterized religion in the Middle Ages. A third force emerged, namely Christian humanism. Here the author is at his brilliant best. Taking up the thesis of D.P. Walker that among the most important achievements of the late fifteenth century was the study of religious movements, such as Pythagoreanism and Hermetism, as pagan anticipations of Christianity, the author weaves the story of the Reformation around the greatest exponent of the New Learning, Erasmus. Luther and Calvin fall into the background. Erasmus’ Greek New Testament published in 1516 (the year before Luther’s thesis at Wittenberg), with its commentary, laid down an essential program of reform which would have made the Reformation unnecessary.

It was too late. “I fear a great revolution is about to take place in Germany,” Erasmus said next year, and he was correct. For every scholar of the standing of Erasmus, More, and Colet, there were wild men who cared only for the destruction of the old order; for every theologian of the stamp of Sadolet and Contanini, there were fanatics such as Paul IV, and cruel, narrowminded administrators like London’s Bishop Bonner under Mary Tudor. Europe had to undergo more than a century of religious war before reason asserted itself once more. The founder members of the Royal Society in 1677 were all sincere Christians, but like others they had begun to doubt the value of institutional Christianity. Feuds and intolerance were embarrassments to their scientific endeavor.

From then on, the issue lay between the forces of reason within the Church and the representatives of institutionalism, of Augustinianism, and of European triumphalism under the guise of Christianity. The author does not mince matters. European missionaries, whether Catholic or Protestant, merely exported overseas their conflicts and divisions. The great chance for Christianity to become the religion of mankind was in the seventeenth century when its impact was new and tremendous, and the discovery of the New World had placed boundless opportunities at its door. It was frittered away. Jesuits clashed with Dominicans and Franciscans in Japan until the Japanese rulers became convinced that all Christians were crypto-revolutionaries and struck with such effect that for the first time in its history Christianity was actually persecuted out of existence.

In the nineteenth century the great Protestant advance was at the expense of primitive animistic cults. Neither the Protestants nor the Catholics could make much impression on the other established religions of mankind, least of all Islam. Today, the vast cathedral built by Cardinal Lavigerie in 1892 on the Byrsa hill at Carthage to symbolize his role as Primate of Africa is deserted, and ready for either conversion into a museum or destruction. In the emergent nations of Africa, Christianity remains an optional extra.

So much of this is true and there is so much of interest in the detailed narrative that words of warning may seem churlish. But this is not a book for beginners in Church history. There are, to start with, far too many errors in simple ascertainable fact. Thus, Constantine’s father had not been a Christian, the Tome of Leo was not a “huge volume” but a fairly lengthy personal letter (six pages of print in Bindley/Green) to his colleague, Flavian of Constantinople; Alexander of Abonuteichos would have been shocked to learn that he was “a leading Montanist.” It was Edessa and not Antioch that saw the riots against Bishop Ibas in 449. Eusebius of Caesarea was consecrated bishop circa 314, and not in 362. It was in Hippo, not Carthage, that the Donatists controlled the public bakery.* The east was not “Arian” between 360-380. Augustine was not writing De Civitate Dei in 398. He did not begin it until after the fall of Rome in 410, and then in reply to pagan charges that Rome had fallen to Alaric because the old protecting gods had been dispossessed by the Christians. This is a random harvest from one section (Section 2) but it warns the reader to be cautious before accepting all the author’s facts.

Advertisement

Usually, the author is generous toward the early heretics. Donatists and Pelagians come off very well. We are shown correctly and lucidly where Apollinaris of Laodicea and Nestorius “went adrift.” Curiously, shorter shrift is given to the Monophysites. Their “doctrinal errors,” according to Johnson, opened the way to the triumph of Islam, which “was itself a version of their heresy,” and they prevented Christian expansion southward from Egypt. Neither statement can be accepted. Southern Arabia in the sixth and early seventh centuries was the scene of a triangular struggle between the Persians supported by Jews and Nestorian Christians, the Byzantines represented by the Monophysite kingdom of Ethiopia, and the Arab tribes. By 600 advantage was passing to the Persian party, and so far as Mahomet’s religion owed anything to Christianity it was to Jewish Christianity, which emphasized Jesus as a prophet but played down his divinity against the Monophysites.

The latter were in fact the great missionaries in the Nile valley, being responsible for the Christianization of the Nubian kingdoms in the sixth century, Ethiopia, and south India. The brilliance of the Nubian Christian civilization revealed by the frescoes of the cathedral at Faras is one of the major discoveries of the last fifteen years, although unmentioned in this book.

One comes now to the writer’s central theme, the fundamental importance of Paul for the spread and shaping of Christianity. No one would deny Paul’s contribution. It is doubtful even if Jesus ever had the idea of spreading his message beyond the confines of Palestinian Jewry. His statement recorded in Matthew 10:23, “Ye shall not have gone over the cities of Israel till the Son of Man be come,” suggests the contrary. But the generation after Paul was strangely un-Pauline. Thus, in the letter from the Church of Rome to that of Corinth dating to about 90-100 AD, known as I Clement, the writer, while loud in his praises for Paul as an individual, makes no reference to Justification or “renewal unto the spirit” or other characteristic Pauline ideas, while Jesus is regarded as the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53, not as a pre-existent angelic being or Personified Wisdom (a second God in the Jewish religion would be unthinkable), and far from End of the Age about to occur, Christians were expected to enjoy a normal length of life.

Nor did Paul leave a tradition of mission behind him. Christianity did spread in the generation after the fall of Jerusalem, but by whose agency we do not know. There was no office of “missioner” in the early Church. If one looks to the background of the spread of early Christianity, Philo of Alexandria (died circa 40 AD) is an almost equally significant figure, the “father of Christian philosophy” and one of the great bridgebuilders between Jewish and Greek modes of thought—infinitely more important than Paul in this respect.

The structure, therefore, that Mr. Johnson has built is not always sound. But for all its mistakes this is a book containing deep insights as well as a majestic sense of history. It is also the work of an Erasmian liberal, one to whom the liberal and humanistic traditions of Christianity—the Pauline “freedom”—are paramount. It is a tragedy for such a person that only in the short pontificate of John XXIII has the Erasmian tradition been represented in the Papacy since the Reformation; while the Anglican Communion, where it is at home (vide the Lambeth decision accepting contraception in 1930), has seemed bound to a Church-State establishment. It is Constantine as against Leo. It is not easy to make a choice. One thing stands out: the Church never was a united body. Diversity is of its very nature. Human arrogance and stupidity, as well as theological and social differences, turn those diversities into divisions. These lessons have still to be learned.

With Ernle Bradford’s study, we move back to Paul. In this book, however, the patriarch of Christianity is absorbed into the determined person with gray beard and piercing eyes, who practically took command of the vessel that was taking him as a prisoner to Rome and saved the lives of passengers, guard, and crew as well as his own. From the vantage point of the wreck in Paul’s Bay, Malta, probably in November 59, we look on Paul’s career, his boyhood in Tarsus, education in Jerusalem, the first traumatic contact with Christianity with the stoning of Stephen, and then conversion and brilliant career as missionary to the Gentiles. There are no great profundities. The reader seeking explanations of allusions in the Pauline letters will have to look elsewhere. He will find a fast-moving and attractively told tale explaining why Paul undertook his journeys, why most of the local Jews he encountered detested him, and how eventually he found himself rescued from both his open enemies and his nominal friends at Jerusalem and despatched to stand trial in Rome. This is a sunny Mediterranean travelogue centered on Paul. Taking it together with the early chapters of Paul Johnson’s study, the reader will find himself a good deal wiser about the origins of Christianity, and even optimistic concerning its future.

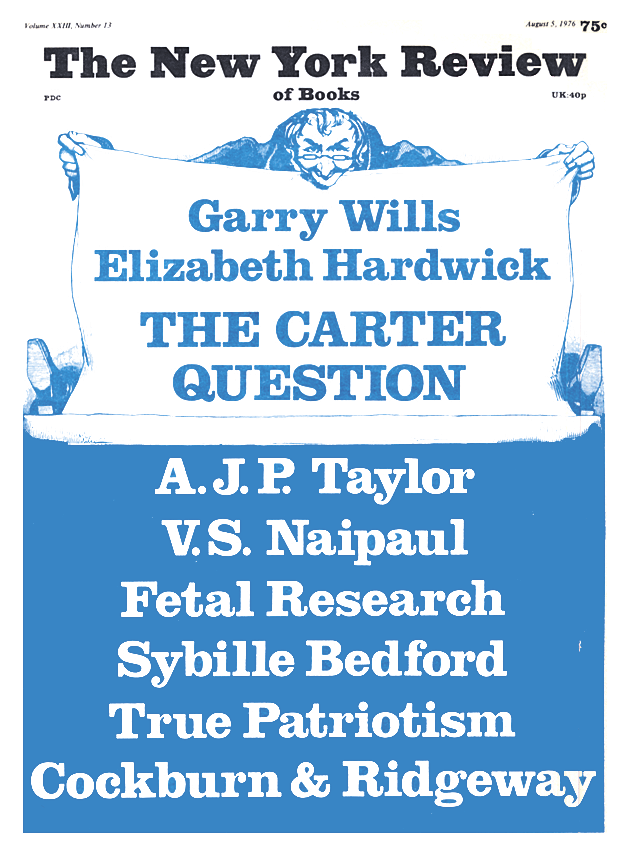

This Issue

August 5, 1976

-

*

See Augustine, Against the letter of Petilian ii.83.184. ↩