In France the 1920s are known as l’époque. The Thirties, less glamorous artistically, though grander far in a destructive way, are called simply les années trente. Both are nevertheless a part of the twenty-year armistice during which Europe and America prepared themselves for going on with the World War. And their artistic history, though it fluttered a bit with the financial tremors of 1929, is a continuous one.

An official view of modern painting and sculpture—long ago set up by collectors, curators, and commission men—assumes aesthetic values, historical values, and monetary values to be identical. This monumental myth is still the operating axiom of art-as-business. The musical spoils of the time, far less controllable by ownership, are still being fought over by the heirs to school-of-Paris modernism and the German publishers, heirs to virtually everything else, including vast resources for promotion.

Literature during those crucial decades, when lives and livings, senses and sensibilities, were evolving in unexpected ways and needed in consequence every freedom for being written about convincingly, turns out to have centered its main progress in Paris. Writing in Russia, in Italy, in the Germanic regions, and in the Iberian peninsula had suffered gravely from government interference. But France still had a tradition of literature as a private enterprise, with a dozen or more prosperous publishers and with authors aplenty. England and America too. But in 1920 Paris was cheaper. It was also exploding with intellectual energies as well as with other enticements for the young, far more so than either the United States or Britain. That is why so much of the best American writing and a good deal of the British took place there.

Actually the British-American literary scene was so full of vigor, so active in poetry, fiction, reporting, and polemics, that it is hard nowadays to distinguish the products of pre-last-war France from the home-grown. Nevertheless, one fact is clear, that the two chief English-language gene-complexes of our century—James Joyce and Gertrude Stein—were carriers of the evolutionary process through a twist of which only one part is native, the other ineluctably Parisian.

One is constantly being asked what it was like, living and working in Paris between the two wars. Not what any particular aspect was like, but all of it, all of life and art and love and food and hygiene. The young, of course, have no idea. And it’s hard explaining that everything, literally everything, was different, even the food.

Artistic values, for instance, were a freely floating currency, though during the Twenties these were still somewhat sensitive to snob favor. In the Thirties another influence appeared, demands for political and sociological cogency, right or left. But during both times the daily press, the liberal or the Catholic weeklies, the far-out fashion monthlies, and the learned quarterlies all were less involved with fomenting consumption than with, at best, expressing amazement, at the worst denouncing the times. This is different from now, believe me, when, more often than not, ideas come ready-made and have a fixed over-the-counter exchange value.

Also, the known leaders of art, music, and letters were not rich and successful celebrities as they largely are now, for the simple reason that they were neither really rich nor really successful. Indeed, though some were of high repute, they were not in our contemporary sense either celebrities or successful. Their work could still be criticized, and was. And very few, save in the Thirties Picasso and Hemingway, owned stocks or bonds or real estate.

Anybody, of course, could feel rich at Paris prices, but only the really rich really were rich. And what did the really rich really do with their riches? They bought châteaux and works of art, wore dresses that were works of art (you can see them now at the Metropolitan Museum). And they patronized art’s workers in the vineyard for no tax deduction. They gambled too, went traveling, had girl friends and gigolos, drank some, read books, amused themselves off hours just like the young and talented, quite often at the same bars and bistros. Being Geniuses Together was what Robert McAlmon called his autobiography, published in 1939. And that is exactly what life was like on the slopes of Montparnasse. Geniuses came in all sizes, all sexes, all disciplines. The smaller ones were admiring public for the larger ones, and the larger ones were careful not to loom.

As Gertrude Stein was to say, “It was not so much what France gave you as what she did not take away.” Certainly many had flocked there after World War I, coming from many countries, many provinces, many Middle Wests. And many had taken on quite early, through simple sincerity, some magical presence. There was lots of magical presence about. And the larger presences, say of both Joyce and Stein, like those of Debussy and Ravel before them, or of Picasso and Braque, were simply around. They could be bitter about one another and refuse to meet, but they saw the same people, frequented the same galleries and bookstores, appeared in the same little mags. They were reputable artists and definitely worth knowing. But they were in no way publicity stars, as Hemingway and Picasso were to become. They were members of a mixed cast, rather, which contained also Ezra Pound and e e cummings and André Gide and Scott Fitzgerald and T. S. Eliot, though the latter proudly kept himself off in England, as did also George Moore and W. B. Yeats.

Advertisement

It was a big cast too, with lots of active talent, and not all of it just American or French or English. There were Italians too, and Belgians and Poles and Romanians, and lots of exiled Russians, and by the mid-Thirties Germans, especially from the learned professions and from the film world. For writing was only a part of what went on, since Paris is by its nature full of painters; and for several years after the death of Diaghilev in 1929 ballet dancers and ballet decorators and ballet composers—including Stravinsky himself—were still to be encountered in the better restaurants and in society.

During all of this time, for twenty years, the two chief modern literatures, English and French, were undergoing (or so it seemed to us) a transformation. But in Paris the book publishers kept up with literary progress no better than those of London and New York. French writers, however, knew how to by-pass this inattention. There was always a master printer around the corner, and an artist friend of some repute to lend illustrations which would help sell a limited edition. If you sold out only part of your edition, moreover, the remaining copies would rise in value. For quite small outlays the French were printing up all their advanced poetry, their surrealist texts polemical and pornographic, their Dada manifestoes. It was only natural that the Anglos should follow. In London, by 1922, small presses were getting busy about T. S. Eliot, in New York about William Carlos Williams. And there were modernist magazines everywhere, some from before World War I, to preview new materials.

The first American to publish in Paris after World War I seems to have been an American journalist, William Bird, who in 1919 or 1920 found his master printer and learned handtypesetting. His first book was by himself, A Practical Guide to French Wines, and a soundly charming book it is, though his main work remained the management in Europe of a Consolidated Press Association. Then in 1921 he met Ernest Hemingway, also a journalist, and Hemingway introduced him to Ezra Pound, who took him to Robert McAlmon.* McAlmon, a naturalistic writer from North Dakota and New York, with money from his English father-in-law, was about to bring out some stories of his own, A Hasty Bunch. The appearance of these in 1922 was simultaneous with the issuing at Sylvia Beach’s bookstore Shakespeare and Company of Ulysses by James Joyce. Both books had been the work of Darantière, a printer in Dijon who knew no English.

Miss Beach, in spite of many solicitations, never again published any book except for two small scripts by Joyce. But McAlmon, at first teaming up with Bill Bird, later on his own, went on putting out, either under his own imprint of Contact Editions or of Bird’s Three Mountains Press, literary texts by himself and by others he had faith in. These books comprised the first-ever by Hemingway (Three Stories and Ten Poems), a first novel by Mary Butts (Ashe of Rings), The Making of Americans by Gertrude Stein, XVI Cantos by Pound, plus more Hemingway (in our time), more Pound (Antheil and the Theory of Harmony), and works of poetry and prose still current by Mina Loy, H. D., Robert Coates, Djuna Barnes, Ford Madox Ford, and W. C. Williams.

Edward Titus, husband of the cosmetics manufacturer and eventual art collector Helena Rubinstein, himself a book dealer and a bibliophile of taste, started publishing in 1926. Along with literary discrimination Titus had also a nose for best sellers, Ludwig Lewisohn’s The Case of Mr. Crump, for instance, Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D. H. Lawrence (its first commercial printing), and Kiki’s Memoirs (introduced by Ernest Hemingway, with portraits by Man Ray, Foujita, Kisling, Per Krogh, and Hermine David plus reproductions of twenty paintings by Kiki). He issued books from 1926 through 1932; and every one was distinguished in both authorship and format, though his choices were a shade more obvious than those of writer-publishers like McAlmon, the Crosbys, and Nancy Cunard.

Harry and Caresse Crosby’s Black Sun Press issued several books of poetry by themselves and some illustrated classics before they got around to their contemporaries. Then they took on Archibald MacLeish, D. H. Lawrence, Kay Boyle, James Joyce, Hart Crane (The Bridge, no less), Bob Brown, and Eugene Jolas, along with early reprints of William Faulkner, Dorothy Parker, McAlmon, Hemingway, and Kay Boyle. They put out French books too in distinguished translations—Les Liaisons dangereuses (Ernest Dowson), René Crevel’s Babylone (as Mr. Knife, Miss Fork, Kay Boyle), Raymond Radiguet’s Le Diable au corps, Charles-Louis Philippe’s Bubu de Montparnasse (also Kay Boyle), Alain-Fournier’s Les Grands Meaulnes, and Vol de Nuit by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (Stuart Gilbert).

Advertisement

There is no doubt that Harry and Caresse Crosby, though neither was quite first-class as a poet, followed with persistence an enlightened policy in publication, possibly Caresse even more so after Harry’s death. Also that their handsome hospitality, drunken parties, and general warmth of radiation (particularly by Caresse) lit up the literary scene so dependably that Harry’s double suicide of 1929 (in New York with a young woman named Josephine) scarcely shook the pattern at all.

In 1928 Bill Bird sold his hand press and his fonts of type for £300 to the Honorable Nancy Cunard and arranged for their shipment to her cottage in Normandy. There, with almost no help from any printer, though there was one near by, she and her house guest of the time, Louis Aragon, mastered the skills of hand-setting and of pressing, and got themselves in the process vast amounts of both fatigue and happiness, printing manuscripts by her elderly admirers Norman Douglas and George Moore, as well as a brilliantly worked out French translation by Aragon of Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark.

Newer works from this Hours Press (eventually returned to Paris and set up in the rue Guénégaud) were early volumes of poetry by Robert Graves and Laura Riding, XXX Cantos by Ezra Pound, Collected Poems by John Rodker, Apollinaire by Walter Lowenfels, Words by Bob Brown, The Revaluation of Obscenity by Havelock Ellis, and Whoroscope by a twenty-four-year-old poet whom nobody knew, Samuel Beckett.

In 1930 Gertrude Stein sold a blue Picasso (Woman with a Fan) to the New York dealer Marie Harriman and set out to publish her own works, long-since a goodly pile and growing. She began her Plain Editions in 1931 with Lucy Church Amiably and ended it in 1932 with Operas and Plays. There were five volumes in all, for the most part poorly printed and poorly bound; but they got her work to circulating. By the next year she had acquired an agent and composed a best-selling autobiography.

During the 1930s Eugene Jolas and Samuel Putnam led the Paris-American publishers, along with Titus, who essayed to revive and keep fresh Ernest Walsh’s earlier magazine This Quarter, a grab-bag of goodies if there ever was one. Jolas’s own magazine transition, another offshoot of This Quarter, benefited initially from the co-editorship of Elliot Paul; and it attracted international attention throughout its eleven-year existence (1927-1938) by printing sizable chunks of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (entitled then simply “Work in Progress”). Its other main line, derived from surrealism, was being polemical about something Jolas called “the Revolution of the Word.”

The Obelisk Press, founded in 1930 by Jack Kahane, English author of light novels, began with Joyce and Richard Aldington, made money on erotica by Radclyffe Hall and Frank Harris, then in 1934 brought out Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, in 1936 Anaïs Nin’s House of Incest, in 1938 Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn. Plagued by censorship and seizures of books in England and in America, as indeed all the braver offshore publishers had been, Kahane eventually found such bannings to be good for sales.

The Obelisk list (1930-1939) is not one of banal pornography, though a flavor of the salable erotic does permeate its thirty-six offerings. The success of Joyce’s Ulysses can probably be credited with some of the epoch’s bookstore enthusiasm for quality erotica (hitherto more rare in English than in the Latin tongues). Certainly it is the father of all Henry Miller’s work, though Céline is the more advertised connection. And along with Stein’s even more radical tongue-twister Tender Buttons, Ulysses is both prophecy and gospel to Jolas’s messianic hope for a “revolution of the word.”

Studies of both the English languages (indeed of Comp. Lit. too, if that is after all where Joyce belongs) have been advanced by Hugh Ford’s book Published in Paris, a detailed examination of how so much writing of major import got printed in Paris between the two wars. This study covers the field quite broadly enough to allow for its being viewed as a panorama. Thus encompassed, it turns out to contain not merely two major and, say, five or six minor characters in search of a printer, but upward of a hundred authors and more than a dozen publishers, two-thirds of whom were themselves consecrated writers. The others, whether drop-outs from millionaire bohemia (into real hard work) like the Crosbys, or adventurers like Titus and Kahane (excited by their own luck), were nonetheless contributors to an achievement. They all by-passed an establishment of blind-as-a-bat publishers, which was doing very little about quality except to pick up bourgeois novelists like Willa Cather and the few really brilliant ones, like Edith Wharton and Scott Fitzgerald, who worshiped wealth.

In this view Robert McAlmon, Nancy Cunard, Bob Brown, Laura Riding, Walter Lowenfels, and the possibly over-consecrated Eugene Jolas take on size not only as warriors but also as artists. McAlmon, for instance, who by the 1930s had come to be viewed as a failed Hemingway, was defended against exactly that attack (from Waverley Root in the Paris Tribune) by Kay Boyle, who pointed out that if a debt were owed, it was from Hemingway to McAlmon, on grounds of precedence at least. Indeed, she contended, a half-dozen or more contemporary authors owed to McAlmon a “debt of influence,” who had been the “sound and almost heedless builder” and Hemingway merely “the gentleman who came in afterward and laid down the linoleum because it was so decorative and so easy to keep clean.”

McAlmon’s stories published by Contact Editions in 1922 and 1923 as A Hasty Bunch, A Companion Volume, and Post-Adolescence are easily identifiable as predecessors (though possibly not unique ones) to the postwar male-oriented naturalism so characteristic of Hemingway and Morley Callaghan. And his accounts of Berlin’s early-Twenties homosexual world in Distinguished Air (Grim Fairy Tales) (Three Mountains Press, Paris, 1925) are surely the model, should one be needed, for similar evocations in The Last of Mr. Norris, by Christopher Isherwood, published in 1935.

Actually Robert McAlmon, early praised by W. C. Williams, by Joyce, by Pound, by Adrienne Monnier, by many of the choicest choosers, and later renounced by them when in the 1930s he turned bitter, is a writer whose time is past; or else it has not yet come. As for myself, admiring of his early fiction and also of his late poetry, I have long viewed him as a victim of unfair treatment. And it has been a pleasure to find in Hugh Ford’s book not only the space he deserves for sustained midwiferies but also for the completeness and the outright brilliance of his comments. It is this kind of abundance, plus Ford’s not really disliking anybody, that has made of Published in Paris the only history of its time that recounts that time convincingly as I remember it, who was of it.

I wish Hugh Ford had kept his helpful lists and index a little cleaner, though with all the material he has handled a few slips may be condoned. When I tried to find out the history of Nancy Cunard’s Negro: An Anthology, which came out in 1934, too late for the Hours Press and certainly much too big a work for hand-setting, the only source I could find listed was Ford himself, mentioned on the jacket flap as editor of the 1970 edition (but still with no publisher named).

Ford himself is too young to have been part of the epoch he describes, and he has known only a few of its figures, old. But he seems to have broken through the lack of understanding so general among today’s young regarding yesterday’s. Certainly he has brought older ones to life full-size and still aglow with their youth, surrounded by one another, getting drunk with one another, and taking drugs and committing suicide and being pompous and silly and quarreling bitterly but quite without malice, because they all bore toward one another a kind of ferocious good will, and they were all doing the same thing as one another, namely, striving to make their writing come out true, afterward to see it decently buried. The number of resurrections that have ensued is pure miracle, as indeed was earlier whatever grace may have surrounded the whole enterprise.

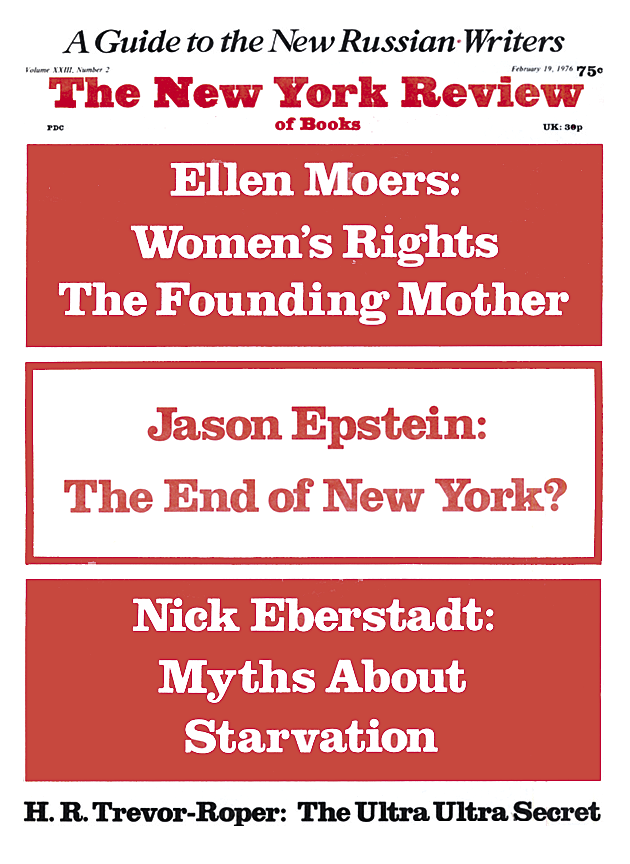

This Issue

February 19, 1976

-

*

There is no significance in two of these pioneers being regular pressmen. In later years many literary authors—Elliot Paul, Eugene Jolas, Robert Sage, Bravig Imbs, Henry Miller—would do casual time on the Paris edition of The [Chicago] Tribune, an easy-going paper not worried about keeping its employees on staff. The Herald (of New York) and The Daily Mail (London), being more particular to hire professionals of the news, were less distinguished in their columns and reviews. ↩