In response to:

Eliot's English Usage from the June 10, 1976 issue

To the Editors:

Some, at least, of Robert Craft’s censures of T.S. Eliot’s prose are ill-founded. Eliot did not put a needless comma (“An artist, happens on a method”); he wrote “An artist happens upon [sic] a method” (To Criticize the Critic, London, 1965, p. 184; as when first printed in the New Statesman, March 3, 1917). Eliot did not omit a needed comma (“it is neither emotion, nor recollection, nor without distortion of meaning, tranquillity”); he wrote “it is neither emotion, nor recollection, nor, without distortion of meaning, tranquility” (Selected Essays, London, 3rd ed., 1951, p. 21; as when first printed in The Egoist, December 1919.

As for Mr. Craft’s preference for “among” where Eliot has “between,” his confidence that all that is in question is an “elementary blunder” should not survive Oxford English Dictionary V. 19: “In all senses, between has been, from its earliest appearance, extended to more than two.” Even Dr. Johnson was less peremptory than Mr. Craft: “Between is properly used of two, and among of more; but perhaps this accuracy is not always preserved.”

Christopher Ricks

Cambridge, England

Robert Craft replies:

Mr. Ricks betrays his lack of a sense of the ridiculous in contributing his research about two commas while failing to see that this only draws attention to the overwhelming number and weight of the remaining “strictures.” More serious, however, is his unjustifiable substitution of “needless”—meaning “unnecessary”—for my very different word “obtrude.” Being a teacher of English, Mr. Ricks might also have mentioned that the second comma occurs in another of those grammatical tangles as exemplified in my letter:

Consequently, we must believe that “emotion recollected in tranquillity” is an inexact formula. For it is neither emotion, nor recollection, nor, without distortion of meaning, tranquillity.

The realization continues to grow that Eliot’s prose was often shockingly bad and that this seems not to be recognized or admitted because of adulation for his poetry.

I erred in assuming that the last edition of the writings of an author of Eliot’s stature would be the most reliable, Mr. Ricks in believing that the first is the authoritative one. Yet with just a little more nit-picking he would have discovered that a later edition of The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism corrects the grammar and even alters the substance of a passage that I quoted in its first form.

My conviction that “among” is indeed preferable to “between” in the cited example has survived a study not only of the out-of-date OED but also of contemporary grammars. Finally, grateful as I am for the quotation from Dr. Johnson, whose dictum so emphatically supports me, I have never been contemporaneous with him; Mr. Rick’s statement “Dr. Johnson was less peremptory than Mr. Craft” lacks an essential present-tense verb.

Robert Craft

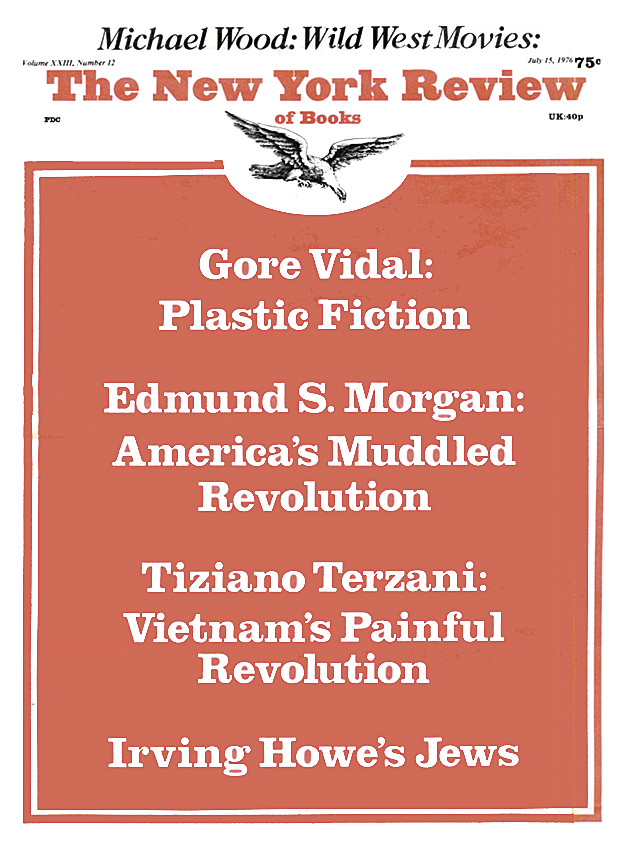

This Issue

July 15, 1976