The engineer who had introduced me to the squatters’ settlement in Bombay was also working on a cooperative irrigation scheme up on the Deccan plateau, some miles southeast of Poona. In India, where nearly everything waits for the government, a private scheme like this, started by farmers on their own, was new and encouraging; and one week I went with the engineer to look.

I joined him at Poona, traveling there from Bombay by the early morning train, the businessman’s train, known as the Deccan Queen. There was no air-conditioned carriage; but on this rainy monsoon morning there was no Indian dust to keep out. Few of the ceiling fans were on; and it was soon necessary to slide down the aluminum-framed window against the chill. Rain and mist over the mainland sprawl of Greater Bombay; swamp and fresh green grass in a land apparently returning to wilderness; occasional factory chimneys and scattered apartment blocks black and seeming to rot with damp; the shanty towns beside the railway sodden, mud walls and gray thatch seemingly about to melt into the mud and brown puddles of unpaved lanes, the naked electric bulbs of tea stalls alone promising a kind of morning cheer.

But then Bombay faded. And swamp was swamp until the land became broken and, in the hollows, patches of swamp were dammed into irregular little ricefields. The land became bare and rose in smooth rounded hills to the plateau, black boulders showing through the thin covering of monsoon green, the fine grass that grows within three days of the first rain and gives these stony and treeless ghats the appearance of temperate parkland.

It doesn’t show from the train, but the Bombay-Poona region is one of the most industrialized in India. Poona, at the top of the ghats, on the edge of the plateau, is still the military town it was in the British days and in the days of the Maratha glory before that, still the green and leafy holiday town for people who want to get away from the humidity of the Bombay coastland. But it is also, and not at all oppressively, an expanding industrial center. Ordered industrial estates spread over what, just thirteen years ago, when I first saw it, was arid waste land. On these estates there has been some reforestation; and it is said that the rainfall has improved.

The plateau around Poona is now in parts like a new country, a new continent. It provides uncluttered space, and space is what the factory-builders and the machine-makers say they need; they say they are building for the twenty-first century. Their confidence, in the general doubt, is staggering. But it is so in India: the doers are always enthusiastic. And industrial India is a world away from the India of bureaucrats and journalists and theoreticians. The men who make and use machines—and the Indian industrial revolution is increasingly Indian: more and more of the machines are made in India—glory in their new skills. Industry in India is not what industry is said to be in other parts of the world. It has its horrors; but, in spite of Gandhi, it does not—in the context of India—dehumanize. An industrial job in India is more than just a job. Men handling new machines, exercising technical skills that to them are new, can also discover themselves as men, as individuals.

They are the lucky few. Not many can be rescued from the nullity of the labor of pre-industrial India, where there are so many hands and so few tools, where a single task can be split into minute portions, and labor can turn to absurdity. The street-sweeper in Jaipur City uses his fingers alone to lift dust from the street into his cart (the dust blowing away in the process, returning to the street). The woman brushing the causeway of the great dam in Rajasthan before the top layer of concrete is put on uses a tiny strip of rag held between her thumb and middle finger. Veiled, squatting, almost motionless, but present, earning her half rupee, her five cents, she does with her finger-dabs in a day what a child can do with a single push of a long-handled broom. She is not expected to do more; she is hardly a person. Old India requires few tools, few skills and many hands.

And old India lay not far from the glitter of new Poona. The wide highway wound through the soft, monsoon-green land. Bangalore was 500 miles to the south; but the village where we were going was only a few hours away. The land there was less green, more yellow and brown, showing its rockiness. The monsoon had been prolonged, but the water had run off into lakes. It was from one such lake that water was to be lifted and pumped up to the fields. The water pipe was to be buried four feet in the ground, not to hamper cultivation of the land when it was irrigated, and to lessen evaporation. Already, early in the morning, the heat of the day still to come, and even in this season of rain, the sky full of clouds, the distant hills cool and blue above the gray lake, heat waves were rising off the rocks.

Advertisement

The nationalized agricultural bank had loaned the farmers 90 percent of the cost of the project. Ten percent the farmers had to pay themselves, in the form of labor; and the engineer had computed that labor at a hundred feet of pipe-trench per farmer. The line of the trench had already been marked; and in the middle of what looked like waste land, the rocks baking in spite of the stiff wind, in the middle of a vast view dipping down to the lake, a farmer with his wife and son was digging his section of the trench.

The man was small and slightly built. He was troubled by his chest and obviously weary. He managed the pickaxe with difficulty; it didn’t go deep, and he often stopped to rest. His wife, in a short green sari, squatted on the stony ground, as though offering encouragement by her presence; from time to time, but not often, she pulled out with a mattock those stones the man had loosened; and the whitecapped boy stood by the woman, doing nothing. Like a painting by Millet of solitary brute labor, but in an emptier and less fruitful land.

A picture of the pain of old India, it might have seemed. But it contained so much that was new: the local agricultural enthusiast who by his example had encouraged the farmers to think of irrigation and better crops, the idea of self-help that was behind the cooperative, the bank that had advanced the money, the engineer with the social conscience who had thought the small scheme worth his while and every week made the long journey from Bombay to superintend, advise, and listen. It wasn’t easy to get qualified men to come out from the city and stay with the project, the engineer said; he had had to recruit and train local assistants.

The digging of the trench had begun the week before. To mark the occasion they had planted a tree, not far from a temple—300 years old, the villagers said—on the top of a hill of rock. The pillars of the temple portico were roughly hewn; the three-domed lantern roof was built up with heavy, roughly dressed slabs of stone. On this plateau of rock the buildings were of stone. Stone was the material people handled with instinctive, casual skill; and the village looked settled and solid and many times built over. In the barrenness of the plateau it was like a living historical site. Old, even ancient, architectural conventions—like the lantern roof of the temple—mingled with the new; unrelated fragments of old decorated stone could be seen in walls.

Four lanes met in the irregularly shaped main square. A temple filled each of two corners; and, slightly to one side in the open space of the square, there was a tree on a circular stone-walled platform. People waiting for the morning bus—luxury!—sat or squatted on the wall below the tree, and on the stone steps that edged the open raised forecourt of one temple. On this forecourt there was a single pillar, obviously old, with a number of bracket-like projections, like a cactus in stone. It was a common feature of temples in Maharashtra, but people here knew as little about its significance as they did elsewhere. Someone said the brackets were for lights; someone else said they were pigeon-perches. The pillar simply went with the temple; it was part of the past, inexplicable but necessary.

The post office was of the present: an ocher-colored shed, with a large official board with plain red lettering. On another side of the square a smaller, gaudier signboard hung over a dark little doorway. This was the village restaurant, and the engineer’s assistants said it was no longer to be recommended. The restaurateur, anxious to extend his food-and-drink business, had taken to supplying some people in the village with water. People too poor to pay in cash paid in chapattis, unleavened bread; and it was these chapattis—the debt-cancelers of the very poor, and more stone than bread—that the restaurateur, ambitious but shortsighted, was now offering with his set meals. He had as a result lost the twice-daily custom of all the engineer’s assistants. They had begun to cook for themselves in a downstairs room of the irrigation project office. And a certain amount of unspoken ill-will now bounced back and forth across the peaceable little square, with every now and then, on either side, the smoke signals of independence and disdain.

Advertisement

The bus came and picked up its passengers, and the dust settled again. At eleven, rather late in the morning, as it seemed, the schoolchildren appeared, the boys in khaki trousers and white shirts, barefooted but with white Gandhi caps, the girls in white blouses and long green skirts. The school was the two-storied panchayat or village council building in one of the lanes off the square, beyond the other temple, which had a wide, smooth, stonefloored veranda, the wooden pillars of the veranda roof resting on carved stone bases. Everywhere there was carving; everywhere doorways were carved. Outside every door hung a basket or pot of earth in which the tulsi or basil grew, sacred to Hindus.

Even without the irrigation scheme, improved agriculture had brought money to this village. Many houses were being renovated or improved. A new roof of red Mangalore clay tiles in a terraced lane announced a brand-new building. It was a miniature, very narrow, with just two rooms, one at the front and one at the back, with shelves and arched niches set in the thick stone walls. A miniature, but the roof had required a thousand tiles, at one rupee per tile: a thousand rupees, a hundred dollars for the roof alone. But that was precisely the fabled sum another man, just a short walk away, had spent on the carved wooden door of his new house, which was much bigger, and half built already, the stone walls already rising about the inset shelves of new wood, the beautifully cut and pointed stone of the doorway showing off the wooden door, already hung: wood, in this land of stone, being especially valuable, and carving, the making of patterns, even in this land of drought and famine, still considered indispensable.

The engineer had remained behind in his office. My guide was now the sarpanch, the chairman of the village panchayat or council; and he, understanding that I was interested in houses, began to lead the way to his own house.

He was a plump man, the sarpanch, noticeably unwashed and unshaved; but his hair was well oiled. He was chewing a full red mouthful of betel nut and he wore correctly grubby clothes, a dingy long-tailed cream-colored shirt hanging out over dingier green-striped pajamas, slackly knotted. The grubbiness was studied, and it was correct because any attempt at greater elegance would have been not only unnecessary and wasteful but also impious, a provocation of the gods who had so far played fair with the sarpanch and wouldn’t have cared to see their man getting above himself.

In the village it was accepted that the sarpanch was blessed: he was distrusted, feared, and envied as a prospering racketeer. Some years before he had collected money for a cooperative irrigation scheme. That money had simply vanished; and there was nothing that anybody could do about it. Since then the sarpanch’s power had if anything increased; and people had to be friendly with him, like the dusty little group scrambling after him now. To anyone who could read the signs the sarpanch’s power showed. It showed in that very full mouth of betel nut that made it difficult for him to speak without a gritty spray of red spittle. It showed in his paunch, which was as it were shaded in appropriate places by an extra griminess on his shirt. The long-tailed shirt, the pajama bottom: the seraglio style of dress proclaimed the sarpanch a man of leisure, or at any rate a man unconnected with physical labor. He was in fact a shopkeeper; and his shop stood next to his house.

From the lane the two establishments did not appear connected. The shop was small, its little front room and its goods quite exposed. The house, much wider, was blank-fronted, with a low, narrow doorway in the middle. Within was a central courtyard surrounded by a wide, raised, covered veranda. At the back, off the veranda, and always shaded from the sun, were the private rooms. It was surprising, after the dust and featurelessness of the lane: this ordered domestic courtyard, the dramatization of a small space, the sense of antiquity and completeness, of a building perfectly conceived.

It was an ancient style of house, common to many old civilizations; and here—apart from the tiles of the roof and the timber of the veranda pillars—it had been rendered all in stone. The design had been arrived at through the centuries; there was nothing now that could be added. No detail was unconsidered. The veranda floor, its stone flags polished by use, sloped slightly toward the courtyard, so that water could run off easily. At the edge of the courtyard there were metal rings for tethering animals (though it seemed that the sarpanch had none). In one corner of the courtyard was the water container, a clay jar set in a solid square of masonry, an arrangement that recalled the tavern counters of Pompeii. Every necessary thing had its place.

A side passage led to a smaller, paved courtyard. This was at the back of the shop, which, according to a notice painted in English on the inside wall, was mortgaged—“hypothecated” was the word used, and it seemed very fierce in the setting—to a bank. And then we were back in the lane.

A man of property, then, a man used to dealing with banks, and, as chairman of the village council, a politician and a kind of official: I thought the sarpanch must be the most important man in the village. But there was a grander: the Patel. The sarpanch was a shopkeeper, a money-man; the Patel was a landowner, the biggest landowner in the village. He owned fifty good acres; and though he didn’t own people, the fate of whole families depended on the Patel. And to these people he was, literally, the Master.

To the house of the Patel, then, we went, by sudden public demand, as it seemed, and in equally sudden procession. The engineer was with us again, and there was a crowd, swamping the group around the sarpanch, who now, as we walked, appeared to hang back. Perhaps the Patel was in the crowd. It was hard to say. In the rush there had been no introductions, and among the elderly turbaned men, all looking like peasants, men connected with the work of the land, no one particularly stood out.

The house was indeed the grandest in the village. It was on two floors, and painted. Bright paint colored the two peacocks carved over the doorway. The blank front wall was thick. Within that wall (as in some of the houses in Pompeii) stone steps led to the upper story, a gallery repeating the raised veranda around the courtyard at ground level. The floor was of beaten earth, plastered with a mixture of mud and cow dung. To the left as we entered, on the raised veranda, almost a platform, were two pieces of furniture: a bed with an old striped bedspread embroidered with the name of the village in nagari characters, and a new sofa of “contemporary” design with naked wooden legs and a covering in a shiny blue synthetic fabric: the Western-style sofa, sitting in the traditional house just like that and making its intended effect, a symbol of wealth and modernity, like the fluorescent light tube above the entrance.

That part of the veranda with the bed and sofa was for receiving visitors. Visitors did not go beyond this to the courtyard unless they were invited to do so. On the raised veranda to the right of the entrance there was no furniture, only four full sacks of grain, an older and truer symbol of wealth in this land of rock and drought. It was a house of plenty, a house of grain. Grain was spread out to dry in the sunlit courtyard; and in the open rooms on either side were wickerwork silos of grain, silos that looked like enormous baskets, as tall as a man, the wickerwork plastered to keep out rats, and plastered, like the floor, with mud and cow dung.

Invited to look around, received now as guests rather than official visitors, we walked past the grain drying in the courtyard to the kitchen at the back. The roof sloped low; after the sunlight of the courtyard it was dark. To the left a woman was making curds, standing over the high clay jar and using one of the earliest tools made by civilized man: a cord double-wound around a pole and pulled on each end in turn: the carpenter’s drill of ancient Egypt, and also the very churning-tool depicted in those eighteenth-century miniatures from the far north of India that deal with the frolics of the dark god Krishna among the pale milkmaids. In the kitchen gloom to the right a chulha or earthen fireplace glowed: to me romantic, but the engineer said that a simple hinged opening in the roof would get rid of the smoke and spare the women’s eyes.

Our visit wasn’t expected, but the kitchen was as clean and ordered as though for inspection. Brass and silver and metal vessels glittered on one shelf; tins were neatly ranged on the shelf below that. And—another sign of modernity, of the new age—from a nail on the wall a transistor radio hung by its strap.

The woman or girl at the fireplace rose, fair, well-mannered in the Indian way, and brought her palms together. She was the Patel’s daughter-in-law. And the Patel (still remaining unknown) was too grand to boast of her attainments. That he could leave to the others, his admirers and hangers-on. And the others did pass on the news about the daughter-in-law of this wealthy man. She was a graduate! Though lost and modest in the gloom of the kitchen, stooping over the fire and the smoke, she was a graduate!

The back door of the kitchen opened on to the back yard; and we were in the bright sun again, in the dust, at the edge of the village, the rocky land stretching away. As so often in India, order, even fussiness, had ended with the house itself. The back yard was heaped with this and that, and scattered about with bits and pieces of household things that had been thrown out but not quite abandoned. But even here there were things to show. Just a few steps from the back door was a well, the Patel’s own, high-walled, with a newly concreted base, and with a length of rope hanging from a weighted pole, a trimmed and peeled tree branch. A rich man indeed, this Patel, to have his own well! No need for him to buy water from the restaurant man and waste grain on chapattis no one wanted. And the Patel had something else no one in the village had: an outhouse, a latrine! There it was, a safe distance away. No need for him or any member of his family to crouch in the open! It was like extravagance, and we stood and marveled.

We re-entered the house of grain and food and graduate daughter-in-law—still at her fireplace—and walked back, around the drying grain in the courtyard, to the front vestibule. We went up the steps set in the front wall to the upper story. It was being refloored: interwoven wooden strips laid on the rafters, mud on that, and on the mud thin slabs of stone, so that the floor, where finished, though apparently of stone, was springy.

Little low doors led to a narrow balcony where, in the center, in what was like a recessed shrine, were stone busts, brightly painted, of the Patel’s parents. This was really what, as guests, we had been brought up to the unfinished top floor to see. The nagari inscription below the busts said that the house was the house of the Patel’s mother. The village honored the Patel as a rich man and a Master; he made himself worthy of that reverence, he avoided hubris, and at the same time he made the reverence itself more secure, by passing it backward, as it were, to his ancestors. We all stood before the busts—bright paint flattening the features to caricature—and looked. It was all that was required; by looking we paid homage.

Even now I wasn’t sure who, among the elderly men with us, was the Patel. So many people seemed to speak for him, to glory in his glory. As we were going down again I asked the engineer, “What is the value of this house? Is that a good question to ask?” He said, “It is a very good question to ask.” He asked for me. It was a question only the Patel himself could answer.

And the Patel, going down the steps, revealed himself, and his quality, by evading the question. If, he said, speaking over his shoulder, the upper flooring was completed in the way it had been begun—the wood, the mud plaster, the stone slabs—then the cost of that alone would be 60,000 rupees, $6,000. And then, downstairs, seating us, his guests, on the visitors’ platform, on the blue-covered modern sofa and the bed with the embroidered bedspread, he seemed to forget the rest of the question.

Tea was ordered, and it came almost at once. The graduate daughter-in-law in the kitchen at the back knew her duties. It was tea brewed in the Indian way, sugar and tea leaves and water and milk boiled together into a thick stew, hot and sweet. The tea, in chipped china cups, came first for the chief guests. We drank with considered speed, held out our cups to surrender them—the Patel now, calm in his role as host, detaching himself from his zealous attendants—and presently the cups reappeared, washed and full of the milky tea for the lesser men.

And the Patel sat below us, in the vestibule, looking like so many of the villagers, a slight, wrinkled man in a peasant-style turban, a dhoti and koortah and brown woolen scarf, all slightly dingy, but mainly from dust and sweat, and not as studiedly grimed as the sarpanch’s shirt and slack pajama bottom. But as he sat there, no longer unknown, but a man who had established his worth, our host, the provider of tea (still being slurped at and sighed over), the possessor of this house (was he boasting about the cost of the new floor?), his personality became clearer. The small, twinkly eyes that might at first, in that wrinkled head, have seemed only peasant’s eyes, always about to register respect and obsequiousness combined with disbelief, could be seen now to be the eyes of a man used to exercising a special kind of authority, an authority that to him and the people around him was more real, and less phantasmal, than the authority of outsiders from the city. His face was the face of the Master, the man who knew men, and whole families, as servants, from their birth to their death.

He said, talking about the great cost of the new floor (and still evading the question about the value of the house), that he didn’t believe in borrowing. Other people believed in borrowing, but he didn’t. He did things only when he had the money to do them. If he made money one year, then there were certain things he felt he could do. That had been his principle all his life; that was how he intended to do the new floor, year by year and piece by piece. And yet he—like the sarpanch, and perhaps to a greater degree than the sarpanch—was almost certainly a money-lender. Many of the people I had seen that morning would have been in debt to the Patel. And in these villages interest rates were so high, 10 percent or more a month, that debts, once contracted, could never be repaid. Debt was a fact of life in these villages; interest was a form of tribute.

But it was also true that when the Patel spoke about borrowing he was not being insincere. The occasion was special. We were outsiders; he had done us the honors of his house; and now, in public audience, as it were, he was delivering himself of his proven wisdom. This was the wisdom that lifted him above his fellows; and this was the wisdom that his attendants were acknowledging with beatific smiles and slow, affirmative swings of the head, even while accepting that what was for the Patel couldn’t be for them.

Now that we were on the subject of money, and the high cost of things these days, we spoke about electricity. There was that fluorescent tube, slightly askew and in a tangle of cord, in the vestibule: it couldn’t be missed. The government had brought electricity to the village five years before, the Patel said; and he thought that 40 percent of the village now had electricity. It was interesting that he too had adopted the official habit of speaking in percentages rather than in old-fashioned numbers. But the figure he gave seemed high, because the connection charge was 275 rupees, over $27, twice a laborer’s monthly wage, and electricity was as expensive as in London.

Electricity wasn’t for the poor. But electricity hadn’t been brought across the plateau just to light the villages. Its primary purpose was to develop agriculture; without electricity the irrigation scheme wouldn’t have been possible. Electricity mattered mainly to the people with land to work. As lighting it was still only a toy. So it was even in the Patel’s house. The fluorescent tube in the vestibule, far from the kitchen and the inner rooms off the veranda, was the only electrical fitting in the house. There were still oil lamps about and they were evidently in daily use.

The fluorescent tube, like the shining blue sofa for visitors, was only a garnish, a modern extra. Sixty percent of the village was without electricity, and village life as a whole still took its rhythm from the even length of the tropical day. Twelve hours of darkness followed twelve hours of light; people rose at dawn and retired at dusk; every day, as from time immemorial, darkness fell on the village like a kind of stultification.

The village had had so little, had been left to itself for so long. After two decades of effort and investment simple things had arrived, but were still superfluous to daily life, answered no established needs. Electric light, ready water, an outhouse: the Patel was the only man in the village to possess them all, and only the water would have been considered strictly necessary. Everything else was still half for show, proof of the Patel’s position, the extraordinariness which yet, fearing the gods, he took care to hide in his person, in the drabness and anonymity of his peasant appearance.

It was necessary to be in the village, to see the Patel and his attendants, to understand the nature of the power of that simple man, to see how easily such a man could, if he wished, frustrate the talk from Delhi about minimum wages, the abolition of untouchability, the abolition of rural indebtedness. How could the laws be enforced? Who would be the policeman in the village? The Patel was more than the biggest landowner. In that village where needs were still so basic, the Patel, with his house of grain, ruled; and he ruled by custom and consent. In his authority, which in his piety he extended backward to his ancestors, there was almost the weight of religion.

The irrigation scheme was a cooperative project. But the village was not a community of peasant farmers. It was divided into people who had land and people who hadn’t; and the people who had land were divided into those who were Masters and those who weren’t. The Patel was the greatest Master in the village. The landless laborers he employed (out somewhere in his fields now) were his servants; many had been born his servants. He acknowledged certain obligations to them. He would lend them money so that they could marry off their daughters with appropriate ceremony; in times of distress they knew that they could turn to him; in times of famine they knew they had a claim on the grain in his house. Their debts would wind around them and never end, and would be passed on to their children. But to have a Master was to be in some way secure. To be untied was to run the risk of being lost.

And the Patel was progressive. He was a good farmer. It was improved farming (and the absence of tax on agricultural income) that had made him a rich man. And he welcomed new ways. Not everyone in his position was like that. There were villages, the engineer said later, when we were on the highway again, which couldn’t be included in the irrigation scheme because the big landowners there didn’t like the idea of a lot of people making more money. The Patel wasn’t like that; and the engineer was careful not to cross him. The engineer knew that he could do nothing in the village without the cooperation of the Patel. As an engineer, he was to help to increase food production; and he kept his ideas about debt and servants and bonded labor to himself.

The countryside was ruled by a network of men like the Patel. They were linked to one another by caste and marriage. The Patel’s daughter-in-law—who might not have been absolutely a graduate: she had perhaps simply gone for a few years to a secondary school—would have come from a family like the Patel’s in another village. She would have exchanged one big house of grain for another; in spite of her traditional kitchen duties she would be conscious of her connections. Development had touched people unequally. To some it had given a glimpse of a new world; others it had bound more fast in the old. Development had increased the wealth, and the traditional authority, of the Patel; it had widened the gap between the landed and the landless. Backed up by people like the sarpanch, minor politicians, minor officials, courted by administrators and the bigger politicians, men like the Patel now controlled; and nothing could be done without them. In the villages they had become the law.

From the Times of India, September 2, 1975: “The Maharashtra chief minister, Mr. S. B. Chavan, admitted in Bombay on Monday that he was aware of big landlords in the rural areas using the local police to drive poor peasants off their land, particularly during the harvest season. Seemingly legal procedures were being used by the police and the landlords to accomplish this purpose, he added.”

On the way back to Poona we stopped at the temple of Zezuri, like a Mughal fort, high up on a black hill. Mutilated beggar children—one girl with flesh recently scooped out of a leg—were hurried out to the lower steps and arranged in postures of supplication. Garish little shrines stained saffron and red, and their patient keepers, all the way up to the temple; archway after archway, eighteenth-century ornamented stucco crumbling over brick; bracketed pillars of varying size and age; on the stone steps, the worn carved inscriptions in various scripts of generations of pilgrims. At the top, on the windy parapet, a view through the Mughal arches of the town’s two tanks or reservoirs (one collapsed and empty) and the monsoon-green plateau in a clouded sunset.

But the rain that had greened the plateau had also, the next morning, made the outskirts of Poona messy: a line of transport office shacks and motor repair shops in yards turned to mud. The busy Poona-Bombay road, badly made, was rutted and broken. In time, going down from the plateau, we came to the smooth, rounded green hills, like parkland, over which rain and shifting mist ceaselessly played: during the monsoon months a holiday landscape to people from the coast, at other times scorched and barren, barely providing pasture for animals. At Lonavala, where we broke our journey, a buffalo herdsman sang in the rain. We heard his song before we saw him, on a hill, driving his animals before him. He was half naked and carried an open black umbrella. When the rain slanted and he held the umbrella at his side it was hard to tell him from his buffaloes.

But the land, though bare, offering nothing or very little, was never empty. All the way from Poona—except in certain defense areas—it was dotted with sodden little clusters of African-like huts: the encampments of people in flight from the villages, people who had been squeezed out and had nowhere else to go, except here, near the highway, close to the towns, exchanging nullity for nullity: people fleeing not only from landlessness but also from tyranny, the rule in a thousand villages of men like the Patel and the sarpanch.

In some parts of central and north-western India men squeezed out or humiliated can take to the ravines and gullies and become dacoits, outlaws, brigands. Whole criminal communities are formed. They are hunted down, and sometimes a district police communiqué gets into the Indian press (“Anti-Dacoit Operation Pays Big Dividends”: Blitz, October 4, 1975). This is traditional; the dacoit leader and the “dacoit queen” are almost figures of folklore. But some years ago there was something bigger. Some years ago, in Bengal in the northeast and Andhra in the south, there was a tragic attempt at a revolution.

This was the Naxalite movement. The name comes from Naxalbari, the district in the far north of Bengal where, in 1968, it all began. It wasn’t a spontaneous uprising and it wasn’t locally led; it was organized by communists from outside. Land was seized and landowners were killed. The shaky, semipopulist government of the state was slow to act; the police might even have been ambivalent; and “Naxalism” spread, catching fire especially in large areas of Andhra in the south. Then the government acted. The areas of revolt were surrounded and severely policed; and the movement crumbled.

But the movement lasted long enough to engage the sympathies of young people at the universities. Many gave up their studies and became Naxalites, to the despair of their parents. Many were killed; many are still in jail. And now that the movement is dead, it is mainly in cities that people remember it. They do not talk about it often; but when they do, they speak of it as a middle-class—rather than a peasant—tragedy. One man put it high: he said that in the Naxalite movement India had lost the best of a whole generation, the most educated and idealist of its young people.

In Naxalbari itself nothing shows and little is remembered. Life continues as before in the green, rich-looking countryside that in places—though the Himalayas are not far away—recalls the tropical lushness of the West Indies. The town is the usual Indian country town, ramshackle and dusty, with its little shops and stalls, its overloaded buses, cycle-rickshaws, carts. It is there, in the choked streets, after the well-tilled and well-watered fields, after the sense of space and of the nearness of the cool mountains, that the overpopulation shows. And yet the land, unusually in India, is not “old.” It was forest until the last century, when the British established tea plantations or “gardens” there, and brought in indentured laborers—mainly from far-off aboriginal communities, pre-Aryan people—to work the gardens.

The tea gardens are now Indian-owned, but little has changed. Indian caste attitudes perfectly fit plantation life and the clannishness of the planters’ club; and the Indian tea men, clubmen now in the midst of the aborigines, have adopted, almost as a sign of caste, and no longer with conscious mimicry, the style of dress of their British predecessors: the shirt, the shorts, and the socks. The tea workers remain illiterate, alcoholic, lost, a medley of tribal people without traditions and now (as in some places in the West Indies) even without a language, still strangers in the land, living not in established villages but (again as in the old plantations of the West Indies) in shacks strung along the estate roads.

There isn’t work for everyone. Many are employed only casually; but this possibility of casual labor is enough to keep people tied to the gardens. In the hours of daylight, with panniers on their backs like natural soft carapaces, the employed flit about the level tea bushes, in the shade of tall rain trees (West Indian trees, imported to shade the tea), like a kind of protected wildlife, diligent but timid, sent scuttling by a sudden shower or the factory whistle, but always returning to browse, plucking, plucking at the endless hedging of the tea bushes, gathering in with each nip the two tender leaves and a bud that alone can be fermented and dried into tea. Tea is one of India’s most important exports, a steady earner of money; and it might have been expected that the tea workers would have been among the most secure of rural workers. They are among the most depressed and—though the estate people say that they nowadays resent abuse—among the most stultified.

But it wasn’t because of the tea workers—that extra level of distress—that the revolutionaries chose Naxalbari. The tea workers were, in fact, left alone. The Naxalbari district was chosen, by men who had read the handbooks of revolution, for its terrain: its remoteness, and the cover provided by its surviving blocks of forest. The movement that began there quickly moved on; it hardly touched the real distress of Naxalbari; and now nothing shows.

The movement is now dead. The reprisals, official and personal, continue. From time to time in the Indian press there is still an item about the killing or capture of “Naxalites.” But social inquiry is outside the Indian tradition; journalism in India has always been considered a gracious form of clerkship; the Indian press—even before the Emergency and censorship—seldom investigated the speeches or communiqués or bald agency items it printed as news. And that word “Naxalite,” in an Indian newspaper, can now mean anything.

The communists, or that group of communists concerned with the movement, interpret events in their own way; they have their own vocabulary. Occasionally they circulate reports about the “execution” of “peasant leaders.” The Naxalite movement—for all its tactical absurdity—was an attempt at Maoist revolution. But was it a “peasant” movement? Did the revolutionaries succeed in teaching their complex theology to people used to reverencing a Master and used for centuries to the idea of karma? Or did they preach something simpler? It was necessary to get men to act violently. Did the revolutionaries then—as a communist journalist told me revolutionaries in India generally should do—preach only the idea of the enemy?

It is the theory of Vijay Tendulkar, the Marathi playwright—who has been investigating this business as someone sympathetic to the Naxalites’ stated cause of land reform, as most Indians are sympathetic—it is Tendulkar’s theory that Naxalism, as it developed in Bengal, became confused with the Kali cult: Kali, “the black one,” the coal-black aboriginal goddess, surviving in Hinduism as the emblem of female destructiveness, garlanded with human skulls, tongue forever out for fresh blood, eternally sacrificed to but insatiable. Many of the Naxalite killings in Bengal, according to Tendulkar, had a ritualistic quality. Maoism was used only to define the sacrifice. Certain people—not necessarily rich or powerful—might be deemed “class enemies.” Initiates would then be bound to the cause—of Kali, of Naxalism—by being made to witness the killing of these class enemies and dipping their hands in the blood.

In the early days, when the movement was far away and appeared revolutionary and full of drama, the Calcutta press published gruesome and detailed accounts of the killings: it was in these repetitive accounts that Tendulkar spotted the ritualism of cult murder. But as the movement drew nearer the city, the press took fright and withdrew its interest. It was as an affair of random murder, the initiates now mainly teenagers, that the movement came to Calcutta, became part of the violence of that cruel city, and then withered away. The good cause—in Bengal, at any rate—had been lost long before in the cult of Kali. The initiates had been reduced to despair, their lives spoiled for good; old India had once again depressed men into barbarism.

But the movement’s stated aims had stirred the best young men in India. The best left the universities and went far away, to fight for the landless and the oppressed and for justice. They went to a battle they knew little about. They knew the solutions better than they knew the problems, better than they knew the country. India remains so little known to Indians. People just don’t have the information. History and social inquiry, and the habits of analysis that go with these disciplines, are too far outside the Indian tradition. Naxalism was an intellectual tragedy, a tragedy of idealism, ignorance, and mimicry: middle-class India, after the Gandhian upheaval, incapable of generating ideas and institutions of its own, needing constantly in the modern world to be inducted into the art, science, and ideas of other civilizations, not always understanding the consequences, and this time borrowing something deadly, somebody else’s idea of revolution.

But the alarm has been sounded. The millions are on the move. Both in the cities and in the villages there is an urgent new claim on the land; and any idea of India which does not take this claim into account is worthless. The poor are no longer the occasion for sentiment or holy alms-giving; land reform is no longer a matter for the religious conscience. Just as Gandhi, toward the end of his life, was isolated from the political movement he had made real, so what until now has passed for politics and leadership in independent India has been left behind by the uncontrollable millions.

(This is the fourth in a series of articles on India.)

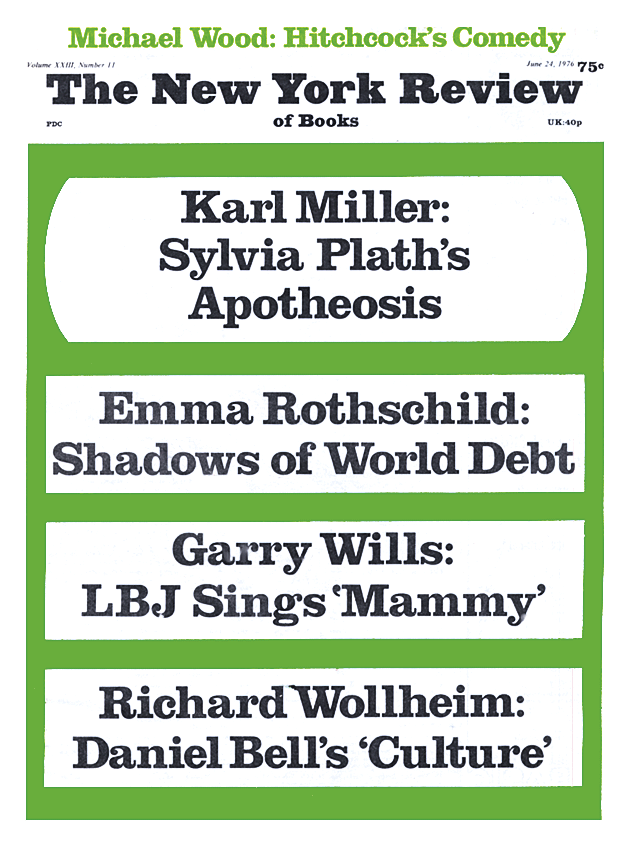

This Issue

June 24, 1976