Roots is about lineage and blood, history and suffering, and the need to know about these things. The need-to-know is Alex Haley’s. Why and how the author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X has driven himself for a dozen years to find his own bloodlines, or one strain at least, is almost as intriguing as the saga that has been the result. The costs have been high in time and energy. The author could hardly have guessed twelve years ago that the work would earn him a million dollars and be one of the major publishing events of the year, but he scoured libraries and archives in two continents, consulted university professors of African history and languages, and read widely in history and anthropology. He lectured freely along the way to keep himself going.

All of this he did to connect the stories his grandmother told on the front porch of her Henning, Tennessee, home with the remote African homeland of the most vivid personality in Grandmother Cynthia’s tales. Her family originated in America, so it had been told through many generations, with a young African named Kunta Kinte, a man so rebellious that he made four attempts to escape his new owner, received as many vicious beatings, and on the last attempt had half his right foot severed in punishment.

As Haley’s story develops (and one cannot tell from the book where Grandmother Cynthia’s story leaves off and Haley’s research begins), young Kunta was brought in 1767 to Annapolis, Maryland, at the age of seventeen, aboard the slaver Lord Ligonier, and soon thereafter taken into Spotsylvania County, Virginia, where he began a long, cruel, and imperfect adjustment to the ways of the white man and his plantation. After monumental effort, and not a little blind luck, Haley found his way back to the African Kunta, alive in the oral tradition of West Africa, stored in the memory of a griot, a village storyteller whose memory bank included, among thousands of other matters, the bloodlines of Kinte’s people, and the very story Grandmother Cynthia herself had told about how young Kunta had met foul play one day when he had gone to the forest to cut wood for a new drum and was captured by slave traders.

One concrete story. Not much perhaps, but enough to convince Haley that he had brought together two oral traditions separated by two centuries, that he had connected his own American family with an ancient and distinguished tradition of West Africa. Haley promises another volume soon that will explain his search for his roots, that will outline the detective work, and perhaps some of the emotional experience that accompanied his own journey from America to Africa and back again. But for the moment we must assume that something stronger than curiosity, and an urge different in more than degree, separates him from the would-be members of the Daughters of the American Revolution or other like-minded patrons of the census room at the National Archives, Haley’s need must have owed not a little to simply knowing the name of the man who made that cruel involuntary journey to America; blood can’t be thicker than water until the name is known. But once it is, honor, justice, and loyalty are possible.

Haley’s need to know must also be related to the particular pain of not knowing shared by most Afro-Americans whose history was so curiously mislaid in America, cast aside as a first sacrifice to survival on the plantations of the New World. Thus Haley’s search becomes the vicarious search of many others who hadn’t Haley’s good fortune in having a Grandmother Cynthia, or for that matter an original Afro-American parent who troubled to stitch American places and things into the memories of his progeny with African names, leaving clues for the Alex Haley yet-to-be to follow, as Theseus followed Ariadne’s thread out of the labyrinth.

In pressing backward with his clues, his stories, his tracing of words like “bolongo” for river (Kamby Bolongo for Gambia River), “yiro” for tree, “tilo” for sun, Haley at last identified two of his potential 124 great-great-great-great-great grandparents, the mother and father of Kunta Kinte, a pair of high birth and enviable social status named Omoro and Binta of the village of Juffure, not far from the Gambia coast. In Haley’s imagining of them, the pair become almost mythical, with the irreducible qualities of parenthood ennobled. They are Moslem, and speak the Mandinka tongue. They provide well for their children, drawing them confidently by proper stages into the rich culture to which they are born. Nobody could be shamed by the grave and dignified Omoro or the accomplished Binta. Nor, one should add, think to shame them either. Their parenting of Kunta reveals more about Haley’s reading in West African anthropology and history than of specific information about this particular couple, but the imagined specifics of their lives and their natures carry the conviction of all stories that have been told many many times: what signifies is not how things were, but how things ought to have been.

Advertisement

If their descendant’s book survives either as literature or as history, which only time will tell, Omoro and Binta Kinte could possibly become the African proto-parents of millions of Americans who are going to admire their dignity and grace. When asked whether and how true Roots is to life, Haley is reported to have responded that it is “factional,” a strange term that suggests that the primary incidents and historical moments are true, but that in reconstructing the emotions of his personalities in the grip of their fates, in supposing their motives, indeed, in filling their mouths with conversation, he has done the best he could, as other writers of historical fiction try to do.

Roots is not precisely a historical novel, because the main carriers of the story were indeed true people. Although it is clear that Haley has few specific facts about the three Africans, Omoro, Binta, and Kunta, even they are more than exclusive constructions of the author’s imagination. Nevertheless there is as much fiction as fact in Roots, some of it designed to lift the spirit, some to amuse, and all of it to tell the collective story of a people. Roots hasn’t the plot of a novel but in following the generations it has instead the spirit as well as the form of a saga.

Sagas are usually told in episodes, and for that reason Roots is particularly well adapted to television. ABC, as modern minstrel, will not be stingy. A record $6 million is going into a sequence of ten installments. A new Juffure has been created in Georgia for filming the village scenes and the slave ship is apparently a shocker of realism. Black residents of the Savannah area serving as secondary characters demanded higher wages when they found how horrible playing captives aboard the slave ship will really be. Success for Haley, and for Georgia, on the scale of Gone With the Wind’s, seems secure; only time will say more, but the signs are auspicious. The first requirement of a saga is that it must keep going, and Roots does. I wouldn’t miss the movie for the world.

Haley has no trouble beginning his saga, and getting it moving. But the problem of characterizing the individual people of so many generations, of making more than a score of persons come alive in the special circumstances of two vastly different cultures, and over a span of two centuries, challenges Haley the artist, and taxes Haley the historian. There are long sections in the book that will cause the historian to call Roots fiction, when literary critics may prefer to call it history rather than judge it as art. For Roots is long and ambitious, and all of its parts are not as good as the best parts.

The splendid opening section on African life is beautifully realized. It is an artistic success. But that the real Juffure of two hundred years ago was anything like the pastoral village Haley describes is not possible. Whatever bucolic character Juffure may have today, it was in the eighteenth century a busy trading center, inhabited by possibly as many as 3,000 people. It was the chief city of Ndanco Sono, the powerful king of Ñomi who tightly controlled (through customs charges) all comings and goings on the Gambia River. He was ever alert to possible infringements of agreements made with the English and the French that might diminish his appointed part of the profits from the slave “factory” on James Island (within full view of Juffure). The king had only to cut off their food and water to bring them to their knees.

In the year Kunta was captured, a commercial war was brewing between Ñomi and the English because of English reluctance to pay the king’s customs for the mere privilege of passing further up the river in pursuit of slave trade.

Ñomi countered by threatening to stop ships from taking on extra crews and interpreters in Ñomi, as they had been doing for decades. The British had the guns of the fort but Ñomi had a fleet of war “canoes,” each carrying forty or fifty men armed with muskets. For a time it was a standoff, but quarrels of this kind rarely led to serious fighting or a long stoppage of trade, since neither side profited when trade stopped altogether.*

It is inconceivable at any time, but particularly under these circumstances, that two white men should have dared to come ashore in the vicinity of Juffure to capture Kunta Kinte, even in the company of two Africans, as Haley describes it. The capture of Kunta, or indeed of any other subject of the king of Ñomi, owner of an estimated one hundred of those formidable “canoes,” would have invited a terrible punishment. It would have been exacted indiscriminately on the crew of the next English ship that Ndanco Sono could lay his hands on.

Advertisement

It could well be that there is an important truth in giving Kunta Kinte a garden of Eden to grow up in that simply outdistances any historical fact. Myth pursues its truth largely outside the realm of reality. But if there were other villages more like the one Haley’s hero grew up in, they were at some distance from Juffure. Actually, the section on Kunta’s childhood owes more to modern anthropology than to history. In fact history seems entirely suspended in the African section. No external events disturb the peaceful roots of Kunta Kinte’s childhood.

Once Haley learned the probable experiences of a Mandinka youth up to the age of seventeen, he simply handed those experiences to Kunta. This works, and Haley has only to relate the passage of time to the idealized life of a lad who learns fast. The scenes in the forest as Kunta travels with his father are memorable for their serenity; when Kunta goes to his training for manhood we share his fear and pride; we understand his complex relations with his brothers, and with his mother, who is, like Juno, occasionally jealous. All of this is clearly Haley’s creation, and not a product of Grandmother Cynthia’s remembering, but these moments are convincing in ways that some of the New World scenes are not.

Conveying the passage of time becomes a serious problem, both aesthetically and historically, after Kunta Kinte reaches America. Haley writes with power, and often with lyrical effect, but his feeling for the probable talk of slaves is often marred by a too-exposed mechanical purpose. He puts these conversations up to little lessons in history that are more distracting than informative. He has difficulty showing how the information picked up at the white man’s dinner table, or from the driver’s seat of the massa’s buggy, or from a surreptitiously read newspaper, is relayed in the kitchen and the quarters. In one scene, for example, the subject is the United States’ undeclared naval war with France of 1798, and Toussaint L’Ouverture’s struggle for an independent black Haiti. The Big-House cook has the floor.

“You ‘members few months back when one dem tradin’ boats got raided somewhere on de big water by dat France?”

Kunta nodded. “Fiddler say he heard dat Pres’dent Adams so mad he sent de whole Newnited States Navy to whup ’em.”

“Well, dey sho’ did. Louvina [the waitress just back from the dining room] jes’ now tol’ me dat man in dere from Richmon’ say dey done took away eighty boats b’longin’ to dat France. She say de white folks in dere act like dey nigh ’bout ready to start singin’ an’ dancin’ ’bout teachin’ dat France a lesson.”

What follows is about “dat Haiti,” where “dat Toussaint” is struggling against a revolt led by a “mulatto” and how “Massa Waller” thinks Toussaint too dumb to run a country, and that “all dem slaves dat done got free in dat Haiti gwine wind up whole lot wuss off dan dey was under dey ol’ massas.” The too frequent “dat” spoils the cadence, which is otherwise not unreasonable, even when it is staged.

Kunta Kinte’s own life poses no such problems about time for Haley, for the process of assimilation is one of the strongest and subtlest themes in Roots. For the miseries of Kunta in the land of “toubob” (white man), the reader will not only feel a vivid sympathy; he may even laugh a little at the incomprehensible ways of Kunta’s captors. There was a word, for instance, that bothered Kunta from the beginning. He heard it often. “What, he wondered, was a nigger?” Kunta, the devout Moslem, was daily offended by the smell and sight of pork, which he never knowingly tasted. (These people “even fed the filthy things.”) Especially effective is the inner contempt the African hero (for that is his role) feels for those of his color who shuffle and scrape when they say “Yassuh, Massa.” Those who had learned this manner of dealing with power returned Kunta’s contempt with a predictable suspicion, for they saw in the African’s wild ways the courage of desperation, and its dangers.

It is all convincing, for we are made to feel that inevitably this is how things happened. We know as well that Kunta must at last bow a little or die, and we know that he will live. We recognize that he will marry Bell because she is kind to him, and looks like a woman of his people. He will marry her in spite of her noisy Christianity and her generous vision of their massa, whom she regards as being a human being, to Kunta an amazing idea. We know that Kunta and Bell must have a child, as they do, so that Grandmother Cynthia may be eventually informed about all that happened to the African while he was discovering so painfully what “nigger” means.

But the account of the external conditions in which Kunta lives in virginia before, during, and after the American Revolution is disconcerting. The reader of any basic book on Southern history will be startled to learn that Kunta was put to work picking cotton in northern Virginia before the Revolution (or ever, really), under the whip of an overseer, in fields loaded with the white stuff “as far as Kunta could see.” Surely this is Alabama in 1850, and not Spotsylvania County, Virginia, in 1767. Haley next employs Kunta at wire fencing, nearly a century ahead of its general use. Okra is a food little known, even now, in the Old Dominion, and the expletive “cracker” has never had much currency there either. This reviewer has not seen the word “redneck” in antebellum writings, and only rarely afterward until it achieved political and pejorative connotations in the twentieth century. “Po white” was the word in Virginia straight along.

These anachronisms are petty only in that they are details. They are too numerous, and chip away at the verisimilitude of central matters in which it is important to have full faith. Are the attitudes ascribed here to whites realistic for the different periods in which they are said to occur? Attitudes toward slaves being taught to read or write? Toward possible insurrection? On the private right of emancipation? In conflating several generations of the institutional history of slavery Haley has only done what most modern historians of slavery tend to do. But the cost of such conflation for a book pursuing a narrative line is naturally higher, and every small confusion of fact, time, or place becomes more exposed.

Haley’s sense of historical setting becomes more sure-footed in the pre-Civil War decades, and after Reconstruction, when the whole family moves under the guidance of the steady blacksmith Tom to Henning, Tennessee. The appearance of such memorable characters as “Chicken George” in a more crowded field of relatives and ancestors enlivens the close of Roots. Chicken George, by reputation the greatest gamecocker in North Carolina, is too fantastic not to be real. His services were won from George’s hapless owner by an English lord in a game at high stakes, and George was carried off to England to train the nobleman’s cockerels. He stayed there more years than his devout wife Matilda cared to recall, but reappeared in his classic style, on horseback, “wearing a flowing green scarf and a black derby with a curving rooster tail feather jutting up from the hatband.” He died in 1890 at the age of eighty-three.

Sagas must have many persons and many stories, many deeds. But there should be one dominant soul, and in Roots it is. Kunta Kinte, whose gloomy intelligence inspires the action through three-fifths of the work. Kunta’s final departure from the book (and not by death) is its most poignant moment, and the subtlest statement on the finality of slavery that this reviewer has read. Kunta has counted the months and years of his bondage by putting a small stone in a gourd every full moon, so that he may eventually determine how many rains (or years) he has lived. Kunta had been twenty rains in toubob’s land before he married Bell, and his beloved daughter Kizzy had soon blessed their love.

It was through Kizzy, and only through her, that the African’s stories were passed to her son, Chicken George, and from him to the somber blacksmith, his son Tom, and on at last to Grandmother Cynthia. Kizzy was not yet twenty herself when the unthinkable (for Kunta and Bell at least) happened in one dreadful morning. With lightning swiftness Kizzy was torn from her parents and turned over to the sheriff, who sold her into another state. Her parents’ high position in “Massa Waller’s” favor could not save her from his wrath when he learned that Kizzy had aided her sweetheart to attempt an escape.

Kunta, felled by a blow from the departing sheriff’s, pistol butt, recovered only to recall in a dazed way what was done in Africa to assure the safe return of traveling loved ones. He limped to his cabin door and scooped up in his hands the clearest print of Kizzy’s foot he could find in the dust. Bursting into his cabin his eye fell upon his gourd as a place to put his dust, but the finality of what had happened then came upon him, and he knew that Kizzy was gone forever.

His face contorting, Kunta flung his dust toward the cabin’s roof. Tears bursting from his eyes, snatching his heavy gourd up high over his head, his mouth wide in a soundless scream, he hurled the gourd down with all his strength, and it shattered against the packed-earth floor, his 662 pebbles representing each month of his 55 rains flying out, ricocheting wildly in all directions.

Halfway into the next page, the reader knows that Kunta too is gone forever, that only through Kizzy could more be learned of her father; only through her could Grandmother Cynthia learn. Only in death or a fairy tale could Kizzy hope to return to Virginia. In its perfect finality, slavery was no fairy tale.

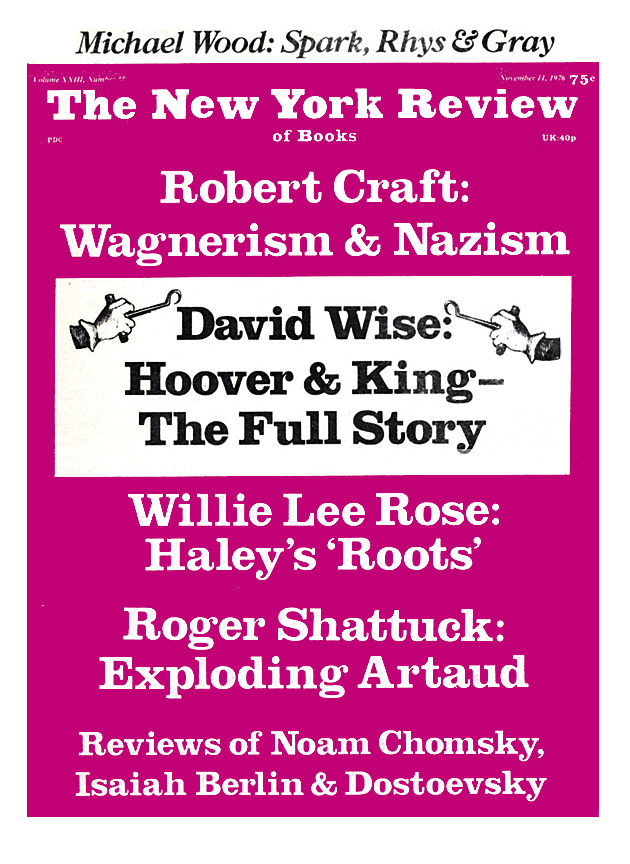

This Issue

November 11, 1976

-

*

Philip D. Curtin, Economic Change in Pre-Colonial Africa: Senegambia in the Era of the Slave Trade (University of Wisconsin Press, 1975), p. 123. ↩