Residual sewer gas from the Watergate explosion has leaked to the surface. John Dean has written a book the aims of which are first to make money and second to disprove Joseph Alsop’s contention that its author is a “bottom-dwelling slug.”

The book may make money.

The new material in Blind Ambition consists mostly of the part of John Dean’s story he was afraid to tell under oath, the palaver that he himself says his lawyer warned him to cut out of his Ervin Committee testimony because it’s too self-serving. This time he doesn’t have anyone around to make him heed good advice, with the result that he invites the book-buying public to spend its money to worry about “my squealer image.” He quotes himself as telling Sam Dash of the Ervin Committee, “I’m getting eaten up by the idea that all I want to do is save my own ass…. I don’t want to be known as just the snitch of Watergate.” Poor fellow. He can’t accept the fact that he is the American ratfink of the twentieth century, so much so that a century hence “to pull a John Dean” may mean to double-cross your pals. Dean might take solace in the fact that millions of us do regard him as a providential bottom-dwelling slug, a slug of extraordinary distinction, a slug to whom we are grateful for eating Richard Nixon’s lettuce rather than our own, but a slug, who, if he was going to write this kind of book, should have entitled it, “The Stoolie’s Return, Or a Twice Told Tale.”

In his promotional efforts to sell his book, Dean has made much of the part played by Jerry Ford in blocking the late Representative Wright Patman’s investigation of where the money came from to pay for the Watergate break-in. Patman’s work was the first congressional look-see at Watergate and it failed because his committee wouldn’t give him subpoena powers. According to Dean, Ford, then the House Minority Leader, did his best to frustrate Patman. Subsequently Ford testified under oath that he hadn’t talked to the White House about the matter, but even if he lied in a minute of panic about the incident, Ford’s part, in stopping Patman doesn’t implicate him in the cover-up. He needed no guilty knowledge to move him to act; that was his job as Minority Leader—protect the party, protect the administration. And what about the Democrats? They held the majority on that committee; according to one of his Democratic colleagues the reason Patman didn’t get the subpoena power was that he got his signals switched and called for a show of hands while his winning votes were caught in traffic on the way in from the airport.

In any event, Dean’s knowledge is hearsay. What he knew from his own eyes and ears he testified to in front of the Ervin Committee and in court so that what’s indisputably correct in the book is old and what’s new is questionable or trivial. Mostly trivial. The nutmeat of the book is a rehash of his testimony, the difference being his testimony is clearer, more concise, and in better English; but it’s available through the Government Printing Office so Dean can’t make any money off it.

Dean’s difficulty is that he was a minor figure in the Nixon White House. A yes-man, a coat-holder and gopher, he made none of the important decisions, wasn’t consulted on them. A felonious functionary, lost in the back office keeping the physical arrangements of the conspiracy tidy, he seldom saw Nixon. He was so low status that he says it was a big, brave thing for him to dare to dial H.R. (Bob) Haldeman directly on the interoffice telephone. Toward the end he was brought in to see Nixon a few more times so that his bosses, alarmed at how badly things were going for them, could check up on their backroom clerk. At some point along the line they seem to have decided that Dean might be more valuable as the centerpiece of a frame-up. This explains, as Dean says, the last meetings with Nixon. They were trying to set him up.

Dean had the nimble shrewdness of the survivor so he turned them in before they could turn him in. They sought each other out and they deserved each other, but Nixon, when he wasn’t acting like a shoplifter loose alone in the White House, was a political man, did have important “policy goals.” Dean by his own description was pursuing his career for a sports car and as much pussy as he could handle. Toward the end of the book Dean has one of the gangsters in the country club jail where he served his four months ask how a twerp like him could get to be the president’s lawyer. “I just kissed a lot of ass, Vinny. A lot of it,” Dean quotes himself as saying. The ass-kisser is now in journalism which should tell us something about that.

Advertisement

Sam Dash calls Dean “a glorified messenger boy” and “a WASP version of What Makes Sammy Run,” in his book, Chief Counsel: Inside the Ervin Committee—The Untold Story of Watergate. Unhappily for him and for us, if there is an untold story of Watergate, Sam Dash doesn’t know it. He does know the inside of the Ervin Committee staff and that story consists of lawyers hiding evidence from each other, intriguing for the premier place in front of the TV cameras at the hearings, and arguing about who would get to examine the most important and publicity-worthy witnesses.

Somebody at Random House must have it in for Dash to let this book go out into the world. A solid third of it should have been red penciled out. An editor who loves an author doesn’t allow sentences like this to get by: “…like a moth attracted by a candle flame he had been drawn to the bright light of Oval Office power and got terribly burned.” That’s worse than Dean’s modified Lizzie Ray style which has people constantly turning white as sheets or ashen faced or feeling it in their gut. But Sam is the loving father moth who battles a thousand miles up the Columbia River every year to mate with the mother salmon. Only parental feelings of such strength would drive even an amateur writer to plug daughter Judi (the i is not mine), who came down to the Committee office and worked as a volunteer. When she was drawn by the bright light of learning back to college (Brown University, you’ll want to know), younger sister Rachel took her place and “experienced the excitement of finding her sister’s I.D. marker in some of the boxes Judi had gone through months before.” Rachel’s excitement was as nothing compared to the reviewer’s when reading about this find.

The book does contain tidbits here and there that historians may want to use, but they’re so specialized that depositing the manuscript in the National Archives would have done as much good as publishing it. Dash writes of Senator Howard Baker and his duplicitous squirmings ‘twixt the conniving jowls in the White House and the gallant investigators in the Senate; we can learn from him a little bit more about the dubious methods of the Justice Department attorneys who first handled the break-in and thereby see how skilled lawyers can legally obstruct justice by nuturing a studied capacity to ignore clues and smudge fingerprints. If those Marx brother prosecutors hadn’t been replaced by Archibald Cox they would have indicted the Sasquatch for ordering the Watergate burglary.

But all of that is of small moment now. Obviously government officials are not going to be particularly diligent in pursuit of those who commit presidentially inspired crimes. In the early months of Watergate, the desire for “containment” went beyond the White House and those eventually convicted of conspiracy to obstruct; it could be said to have included virtually everyone who might have had anything to do with it in the Justice Department or in the press and television. Historians will be more interested in why the containment stopped and the president was exposed. About this Dash has nothing new to offer, even though he was one of the instruments in uncovering the cover-up.

He sees it as a law case, a big, famous law case. His book begins with his being offered the job of handling the case. In fact, all three of these books, Jaworski’s also, begin with their authors being offered the job, for each in his own way sees himself in this drama as a professional pursuing his career.

For these men a person is as good or as significant as the law school he graduated from. Dash seems to think that one who graduates from the Harvard Law School has attained a higher state of being, while those who lack an LLD are women, probably wives, or non-persons. Put these three books together and you get some inkling about what matters to lawyers and you find out it’s office furniture. Dash, and Dean especially, give over much space to recounting how they got their offices and what they put in them. Jaworski, although he describes his office, thinks it’s more important to speak of his protocol battles, how he lowered himself to make the first call to this fella and humbled himself to get in the limo to visit that fella.

Advertisement

The profession of law itself is an obstruction of justice. Inside the White House the same legal professionalism which would make the secret bombing of Cambodia irrelevant to the case against Nixon guided Dean and convinced him that cute legal tricks would save him from culpability. It’s all right to coach an act of perjury, just don’t advise it. Outside the White House Jaworski and ten dozen other members of the bar were constructing the narrowest possible case, limiting, cutting back, letting people off, diminishing the charges, securing token convictions with suspended sentences thereby assuring the defendants’ silence. Jaworski’s book, bearing the information on the cover that its author is the recipient of ten honorary degrees, tells us that, although he won’t phrase it this way, his principal function in coming to Washington was to dampen the thing down, minimize the losses and close out the books as rapidly as possible. There’s no other conclusion you can come to after reading his description of how he handled Haldeman’s attempt to plea bargain.

Haldeman may be as important as Nixon. He was the only one who was on both sides of the Oval Office door, the man whose mouth Nixon spoke through, who issued orders in Nixon’s name. To an extraordinary degree Nixon only manifested himself as a decision maker and chief executive through the aspect of the brush-cut Haldeman. By Jaworski’s own account no effort was made to see if Haldeman would talk in return for being allowed to plead to a lesser charge with a lighter sentence. Jaworski, it would seem, wanted to do with Haldeman what the lesser federal prosecutors had done with the original burglars—keep them from pleading guilty so they didn’t spill their guts. In addition we have Jaworski’s account of how he prevented Nixon from being indicted, how he encouraged Ford to pardon Nixon, and how he arranged for the special treatment for John Connally.

Jaworski’s part in Watergate aside, this is a bad, bad book. A good editor might have salvaged Dash’s into something halfway presentable, but this job is too boring to be entertainment, too pat to be worth much as history, too obtuse for political science. It’s of vanity press quality but no fewer than three publishers have their names on it, Thomas Y. Crowell, Reader’s Digest Press, and the Gulf Publishing Company of Houston. There is also a statement in the front saying that all revenues from it will go to the Leon Jaworski Foundation, an institution that doubtless awards four-year scholarships to Texas A & M to the young person with the finest patriotic exhibit at the Austin State Fair. You get the feeling about this book that it’s subsidized political propaganda, that hundreds of thousands of copies of the damn thing are going to be given out in Sunday schools and weekday schools, too. The outward appearances suggest that this thing was cranked out to give the kiddies a hero in place of Nixon and to explain, if the US of A is the chosen of God and the Constitution was written by the Holy Ghost, how the unbroken, two-century line of saintly leaders and holy and venerable chief executives came to be interrupted by the reign of Richard. Jaworski’s book may not be the entire official story as it’s being worked out and elaborated, but it is the part which tells how paradise was regained and the saints resumed their seats in the city of the great federal dome.

This is a book which first makes you sleepy and then makes you angry. It’s so blandly superior with its hoity-toity Church of England title. The Right and the Power. We know who Jaworski thinks he is but he might keep it to himself. The worst, with all of these guys, but with Jaworski most of all, is that they think they are so great we will even care about the housekeeping details of their lawyerly lives. Jaworski has to write a paragraph on how he came to get a full-sized refrigerator in his Washington hotel suite; he has to give us his wife’s recipe for spaghetti and he has to tell us, “I managed to keep up with my jogging, a custom for years. I would jog at a fast pace from bedroom to bedroom while Jeannette [she’s the much loved and respected old ball-and-chain] was preparing breakfast, zigzagging around her as she moved from the kitchen to the sitting room, where we ate.”

Damn them, damn them, they’ll tell us the state of their bowels and how their hearts murmur, but they won’t tell us the truth.

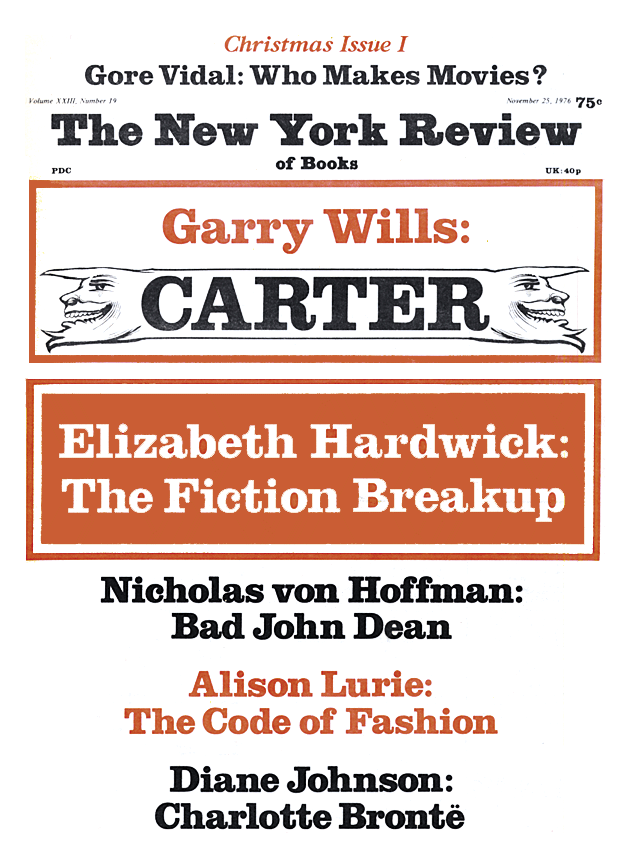

This Issue

November 25, 1976