Psychiatric self-help, the twentieth century’s equivalent of “self-culture,” commends itself as the shortest road to health and happiness, at least for those who can’t afford regular visits to a psychiatrist. The market for books of psychiatric advice and consolation appears inexhaustible. The style of these manuals, however, has recently undergone a certain refinement. Exhortation has yielded to analysis, positive thinking to study of the laws of psychological development. The popularization of psychiatric jargon and concepts has created a half-knowledgeable readership that can no longer be satisfied with slogans and proverbs, formulas for winning friends and influencing people, injunctions to keep smiling.

The agreeable fiction that life begins at forty no longer invites a willing suspension of disbelief. We know too much about the “mid-life crisis” to find comfort in such pieties. Today we insist that our doctors tell us the worst; we find our chief comfort in the knowledge that others get the same diagnosis. Others share our fears, dread the prospect of aging as much as we do, and yet in some cases seem to have found means of psychic survival. We used to read about the rich and famous in order to learn and emulate the secrets of their success; now we also need to be reassured that they suffer the same anxieties, the same despair, the same fear of mirrors that afflict the lowly.

The principle that misery loves company—the more exalted the better—explains the current fascination with the “stages of life.” If life no longer begins at forty, at least a common fate awaits us all—a slow descent, the pains of which, according to the new psychological realism, cannot be eased by closing our eyes to the aging process. The only protection against the unpleasant facts of “development,” according to Gail Sheehy, is to look them squarely in the face. This is cold comfort compared to what used to be held out by the upholders of mind over matter, but it rests on better psychology and a more realistic understanding of human limitations.

Such at least is the reader’s first impression of Passages, one to which the book owes much of its success. Yet the impression of psychological realism is deceptive. At heart, Gail Sheehy believes in the power of positive thinking. She has too much sense of her audience, however, to try to convince us that youthful thoughts will keep us young. Indeed she deplores the cult of youth. Her approach to the “predictable crises of adult life” nevertheless continues the tradition of Mary Baker Eddy, Dale Carnegie, and Norman Vincent Peale.

The book consists of material derived in part—some say, appropriated—from developmental psychologists like Erik Erikson and Roger Gould, in part from the author’s interviews with the affluent and educated. It offers the reader the knowledge that he is in the “good company,” as Sheehy puts it, of people with fictionalized names like Vanessa, Marabel, and Melissa—beautiful people who nevertheless experience the “trying twenties,” the “midlife passage,” the “deadline decade” in all their inescapable intensity. Their money and advantages do not protect these suburbanites against the predictable panic of middle age. Even our betters, it appears, adopt the usual self-defeating strategies for dealing with that panic—love affairs with younger partners, face lifts, hair transplants. Sheehy condemns not only the cult of youth but the illusion of individuality—the illusion that anyone escapes the “identity crisis” of early adulthood or the “crisis of authenticity” that comes with middle age. Not even Marabel and Melissa, in their well-appointed surroundings, escape. The question is not whether we will undergo these crises, according to Sheehy, but whether they come as a catastrophe or as an opportunity for further “growth.”

Sheehy wrote her book, she says, after experiencing a mid-life crisis of her own, and it is middle age, more than earlier “passages,” that especially interests her. She is now convinced that the way to make the best of middle age is to prepare for it and that the most important part of this preparation is knowing “what to expect.” It helps to know that fear of aging, dissatisfaction with your job, boredom with your life, rising marital tension, and a restless search for new experience are “perfectly natural at this stage.” For that matter, earlier crises are also “natural.” The self-questioning of early adulthood; the “couple puzzle” of the late twenties and early thirties, when the man is rising in his career while the woman stagnates at home; the male “climacteric”; the female menopause are “perfectly normal” events appropriate to a given stage of life, and their disruptive influence can be minimized, Sheehy thinks, by understanding this and by getting ready for trouble ahead of time.

Clearly the greatest appeal of this book, which has kept it at the top of nonfiction bestseller lists ever since its publication, lies not in its cute catchwords but in the stress on the predictability and regularity of crisis. As one reviewer has already pointed out, Sheehy does for adulthood what Spock did for childhood. Both assure the anxious reader that conduct he finds puzzling or disturbing, whether in his children, his spouse, or himself, can be seen as merely a normal phase of emotional development.

Advertisement

Reassurance of this sort can easily backfire, however. It may be comforting to know that a two-year-old child likes to contradict his parents and often refuses to obey them, but if the child’s development fails to conform to the proper schedule, the parent will be alarmed and seek medical or psychiatric advice, which may stir up further fears. The application of developmental psychology to adult life will probably have the same effect. Measuring experience against a normative model set up by doctors, people will be as troubled by departures from the norm as they are troubled by the “predictable crises” themselves, against which medical norms are intended to provide reassurance. The spirit of Sheehy’s book—like that of Spock’s famous manual on child-care—is generous and humane, but it rests on medical definitions of reality that remain highly suspect, not least because they make it so difficult for us to get through life without the constant attention of doctors, psychiatrists, and faith-healers. Sheehy brings to the subject of aging, which needs to be approached from a moral and philosophical perspective, a therapeutic sensibility incapable of transcending its own limitations. She understands that there is something wrong—not merely wasteful but ethically indecent—about the way our society approaches the problems of aging, but the psychiatric perspective she has adopted, far from clarifying or helping to alleviate those problems, in many ways makes them worse.

The normative concept of developmental stages inevitably promotes a view of life as an obstacle course, in which the aim of life is simply to get through the course with a minimum of trouble and pain. When existence has no meaning beyond itself, survival becomes the only object. Survival techniques—the ability to manipulate what Sheehy refers to, using a medical metaphor, as “life-support systems”—represent the highest form of wisdom: the knowledge that gets us through without “panic.” Those who master Sheehy’s “no-panic approach to aging” will be able to say, in the words of one of her subjects, “I know I can survive…I don’t panic any more.” This is hardly an exalted form of satisfaction, however. “The current ideology,” Sheehy writes, “seems a mix of personal survivalism, revivalism, and cynicism”; but her own book does not challenge this ideology, merely restates it in more “humanistic” form.

Sheehy recognizes that wisdom is one of the few comforts of age, but she does not see that to think of wisdom purely as a consolation divests it of any larger meaning or value. The real value of the accumulated wisdom of a lifetime is that it can be handed on to future generations. Our society, however, has lost this conception of wisdom and knowledge. It holds an instrumental view of knowledge, according to which technological change constantly renders knowledge obsolete and therefore non-transferable. The older generation has nothing to teach the younger, according to this kind of reasoning, except to equip it with the emotional and intellectual resources to make its own choices and to deal with “unstructured” situations for which there are no reliable precedents or precepts. It is taken for granted that children will quickly learn to find their parents’ ideas old-fashioned and out of date, and parents themselves tend to accept the social definition of their own superfluity.

Having raised their children to the age at which they enter college or the work force, people in their forties and fifties find that they have nothing left to do as parents. This discovery coincides with another, that business and industry no longer need them either. The superfluity of the middle-aged and elderly originates in the severence of the sense of historical continuity. The older generation no longer thinks of itself as living on in the next; it no longer achieves a vicarious immortality in posterity. Under these conditions, the old find it difficult to give way gracefully to the young. They cling to the illusion of youth until it can no longer be maintained, at which point they must either accept their superfluous status or sink into dull despair. Neither solution makes it easy to sustain much interest in life.

Sheehy appears to acquiesce in the devaluation of parenthood, for she has almost nothing to say about it. Nor does she criticize the social pressures that push people out of their jobs into increasingly early retirement. Indeed she accepts this trend as desirable. “A surprisingly large number of workers are choosing to accept early retirement,” she says brightly, “provided it will not mean a drastic drop in income.” Her solution to the mid-life crisis is to find new interests, new ways of keeping busy. She equates growth with keeping on the move. She urges her readers to discover “the thrill of learning something new after 45.” Take up skiing, golf, or hiking. Learn to play the piano. You won’t make much progress, “but so what!…The point is to defeat the entropy that says slow down, give it up, watch TV, and to open up another pathway that can enliven all the senses, including the sense that one is not just an old dog.”

Advertisement

Under a veneer of psychological realism, Sheehy extols the power of positive thinking. “More than anything else, it is our own view of ourselves that determines the richness or paucity of the middle years.” In effect, she urges people to prepare for the “mid-life crisis” so that they can be phased out without making a fuss. Under existing arrangements, this may be the best we can expect, but it should not be disguised as “renewal” and growth. At best, it enables us to get through the days.

The psychology of growth, development, and “self-actualization,” which gives to Sheehy’s book a spurious air of objectivity and realism, rests on deception. It presents survival as spiritual progress, resignation as renewal. In a society in which most people find it difficult to store up experience, knowledge, and even money against old age, or to pass on accumulated experience to their descendants, the growth experts compound the problem by urging the middle-aged to cut their ties to the past, embark on new careers and new marriages (“creative divorce”), take up new hobbies, travel light, and keep moving.

This is a recipe not for growth but for planned obsolescence. It is no wonder that American industry has embraced “sensitivity training” as an essential part of personnel management. The new therapy provides for personnel what the annual model-change provides for its products: rapid retirement from active use. Corporate planners have much to learn from Gail Sheehy’s popularization of humanistic psychology, which provides techniques by means of which people can phase themselves out of active life, often prematurely, painlessly, and without “panic.”

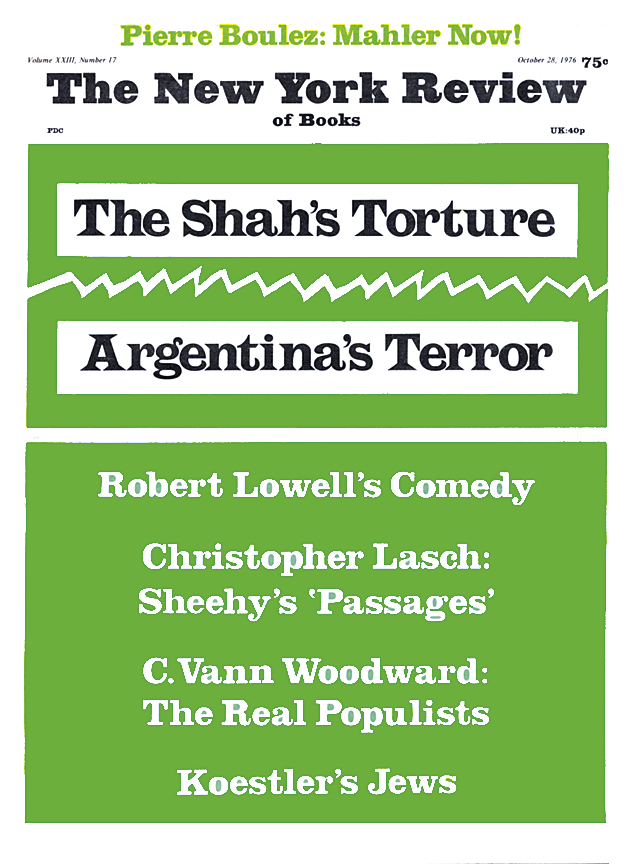

This Issue

October 28, 1976