Le Carré’s new novel is about twice as long as it should be. It falls with a dull thud into the second category of le Carré’s books—those which are greeted as being something more than merely entertaining. Their increasingly obvious lack of mere entertainment is certainly strong evidence that le Carré is out to produce a more respectable breed of novel than those which fell into the first category, the ones which were merely entertaining. But in fact it was the merely entertaining books that had the more intense life.

The books in the first category—and le Carré might still produce more of them, if he can only bring himself to distrust the kind of praise he has grown used to receiving—were written in the early and middle Sixties. They came out at the disreputably brisk rate of one a year. Call for the Dead (1961), A Murder of Quality (1962), The Spy Who Came In From the Cold (1963), and The Looking Glass War (1965) were all tightly controlled efforts whose style, characterization, and atmospherics were subordinate to the plot, which was the true hero. Above all, they were brief: The Spy Who Came In From the Cold is not even half the length of the ponderous whopper currently under review.

Elephantiasis, of ambition as well as reputation, set in during the late Sixties, when A Small Town in Germany (1968) inaugurated the second category. Not only was it more than merely entertaining, but it was, according to the New Stateman’s reviewer, “at least a masterpiece.” After an unpopular but instantly forgiven attempt at a straight novel (The Naïve and Sentimental Lover), the all-conquering onward march of the more than merely entertaining spy story was resumed with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), which was routinely hailed as the best thriller le Carré had written up to that time.

The Honourable Schoolboy brings the second sequence to a heavy apotheosis. A few brave reviewers have expressed doubts about whether some of the elements which supposedly enrich le Carré’s later manner might not really be a kind of impoverishment, but generally the book has been covered with praise—a response not entirely to be despised, since The Honourable Schoolboy is so big that it takes real effort to cover it with anything. At one stage I tried to cover it with a pillow, but there it was, still half visible, insisting, against all the odds posed by its coagulated style, on being read to the last sentence.

The last sentence comes 530 pages after the first, whose tone of myth-making portent is remorselessly adhered to throughout. “Afterwards, in the dusty little corners where London’s secret servants drink together, there was argument about where the Dolphin case history should really begin.” The Dolphin case history, it emerges with stupefying gradualness, is concerned with the Circus (i.e., the British Secret Service) getting back on its feet after the catastrophic effect of its betrayal by Bill Haydon, the Kim Philby figure whose depredations were the subject of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. The recovery is masterminded by George Smiley, nondescript hero and cuckold genius. From his desk in London, Smiley sets in motion a tirelessly labyrinthine scheme which results in the capture of the Soviet Union’s top agent in China. Hong Kong is merely the scene of the action. The repercussions are worldwide. Smiley’s success restores the Circus’s fortunes and discomfits the KGB. But could it be that the Cousins (i.e., the CIA) are the real winners after all? It is hard to tell. What is easy to tell is that at the end of the story a man lies dead. Jerry Westerby, the Honourable Schoolboy of the title, has let his passions rule his sense of duty, and has paid the price. He lies face down and lifeless, like someone who has been reading a very tedious novel.

This novel didn’t have to be tedious. The wily schemes of the Circus have been just as intricate before today. In fact the machinations outlined in The Spy Who Came In From the Cold and The Looking Glass War far outstrip in subtlety anything Smiley gets up to here. Which is part of the trouble. In those books character and incident attended upon narrative, and were all the more vivid for their subservience. In this book, when you strip away the grandiloquence, the plot is shown to be perfunctory. There is not much of a story. Such a lack is one of the defining characteristics of le Carré’s more recent work. It comes all the more unpalatably from a writer who gave us, in The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, a narrative so remarkable for symmetrical economy that it could be turned into an opera.

Advertisement

Like the Oscar Wilde character who doesn’t need the necessary because he has the superfluous, le Carré’s later manner is beyond dealing in essentials. The general effect is of inflation. To start with, the prose style is overblown. Incompatible metaphors fight for living space in the same sentence. “Now at first Smiley tested the water with Sam—and Sam, who liked a poker hand himself, tested the water with Smiley.” Are they playing cards in the bath? Such would-be taciturnity is just garrulousness run short of breath. On the other hand, the would-be eloquence is verbosity run riot. Whole pages are devoted to inventories of what can be found by way of flora and fauna in Hong Kong, Cambodia, Vietnam, and other sectors of the mysterious East. There is no possible question that le Carré has been out there and done his fieldwork. Unfortunately he has brought it all home.

But the really strength-sapping feature of the prose style is its legend-building tone. Half the time le Carré sounds like Tolkien. You get visions of Hobbits sitting around the fire telling tales of Middle Earth.

Need Jerry have ever gone to Ricardo in the first place? Would the outcome, for himself, have been different if he had not? Or did Jerry, as Smiley’s defenders to this day insist, by his pass at Ricardo, supply the last crucial heave which shook the tree and caused the coveted fruit to fall?

Forever asking questions where he ought to be answering them, the narrator is presumbly bent on seasoning mythomania with Jamesian ambiguity: The Lord of the Rings meets The Golden Bowl. Working on the principle that there can be no legends without lacunae, the otherwise omniscient author, threatened by encroaching comprehensibility, takes refuge in a black cloud of question marks. The ultimate secrets are lost in the mists of time and/or the dusty filing cabinets of the Circus.

Was there really a conspiracy against Smiley, of the scale that Guillam supposed? If so, how was it affected by Westerby’s own maverick intervention? No information is available and even those who trust each other well are not disposed to discuss the question. Certainly there was a secret understanding between Enderby and Martello….

And after a paragraph like that, you get another paragraph like that.

And did Smiley Know of the conspiracy, deep down? Was he aware of it, and did he secretly even welcome the solution? Peter Guillam, who has since had two good years in exile in Brixton to consider his opinion, insists that the answer to both questions is a firm yes….

Fatally, the myth-mongering extends to the characterization. The book opens with an interminable scene starring the legendary journalists of Hong Kong. Most legendary of them all is an Australian called Craw. In a foreword le Carré makes it clear that Craw is based on Dick Hughes, legendary Australian journalist. As it happens, Australian journalists of Hughes’s stature often are the stuff of legend. In the dusty little corners where London’s journalists do their drinking, there is often talk of what some Australian journalist has been up to. They cultivate their reputations. After the Six Day War one of them brought a jeep back to London on expenses. But the fact that many Australian journalists are determined to attain the status of legend does not necessarily stop them being the stuff of it. Indeed Hughes has been used as a model before, most notably by Ian Fleming in You Only Live Twice. What is notable about le Carré’s version, however, is its singular failure to come alive. Craw is meant to be a fountain of humorous invective, but the cumulative effect is tiresome in the extreme.

“Your Graces,” said old Craw, with a sigh. “Pray silence for my son. I fear he would have parley with us. Brother Luke, you have committed several acts of war today and one more will meet with our severe disfavour. Speak clearly and concisely omitting no detail, however slight, and thereafter hold your water, sir.”

Known to be an expert mimic in real life, le Carré for some reason has an anti-talent for comic dialogue. Craw’s putatively mirth-provoking high-falutin’ is as funny as a copy of The Honourable Schoolboy falling on your foot. Nor does Craw do much to justify the build-up le Carré gives him as a master spy. The best you can say for him is that he is more believable than one of his drinking companions, Superintendent “Rocker” Rockhurst, the legendary Hong Kong policeman. “Rocker” Rockhurst? There used to be a British comic-strip character called Rockfist Rogan. Perhaps that was the derivation. Anyway, it is “Rocker” Rockhurst’s main task to preserve order among the legendary Hong Kong journalists, who are given to drinking legendary amounts, preparatory to engaging in legendary fist-fights. Everything that is most wearisome about journalism is solemnly presented as the occupation of heroes. No wonder, then, that espionage is presented as the occupation of gods.

Advertisement

Le Carré used to be famous for showing us the bleak, tawdry reality of the spy’s career. He still provides plenty of bleak tawdriness, but romanticism comes shining through. Jerry Westerby, it emerges, has that “watchfulness” which “the instinct” of “the very discerning” describes as “professional.” You would think that if Westerby really gave off these vibrations it would make him useless as a spy. But le Carré does not seem to notice that he is indulging himself in the same kind of transparently silly detail which Mark Twain found so abundant in Fenimore Cooper.

It would not matter so much if the myth-mongering were confined to the minor characters. But in this novel George Smiley completes his rise to legendary status. Smiley has been present, on the sidelines or at the center, but more often at the center, in most of le Carré’s novels since the very beginning. In Britain he has been called the most representative character in modern fiction. In the sense that he has been inflating almost as fast as the currency, perhaps he is. His latest appearance should make it clear to all but the most dewy-eyed that Smiley is essentially a dream.

It could be, of course, that he is a useful dream. Awkward, scruffy, and impotent on the outside, he is graceful, elegant, and powerful within. An impoverished country could be forgiven for thinking that such a man embodies its true condition. But to be a useful dream Smiley needs to be credible. In previous novels le Carré has kept his hero’s legendary omniscience within bounds, but here it springs loose. “Then Smiley disappeared for three days.” Sherlock Holmes, it will be recalled, was always making similarly unexplained disappearances, to the awed consternation of Watson. Smiley’s interest in the minor German poets recalls some of Holmes’s enthusiasms. But at least the interest in the minor German poets was there from the start (vide “A Brief History of George Smiley” in Call for the Dead) and was not tacked on later à la Conan Doyle, who constantly supplied Holmes with hitherto unhinted-at areas of erudition. Conan Doyle wasn’t bothered that the net effect of such lily-gilding was to make his hero more vaporous instead of less. Le Carré, though, ought to be bothered. When Smiley, in his latest incarnation, suddenly turns out, at the opportune moment, to be an expert on Chinese naval engineering, his subordinates might be wide-eyed in worship, but the reader is unable to resist blowing a discreet raspberry.

It was Smiley, we now learn, who buried Control, his spiritual father. (And Control, we now learn, had two marriages going at once. It is a moot point whether or not learning more about the master plotter of The Spy Who Came In From the Cold leaves us caring less.) We get the sense, and I fear are meant to get the sense, of Camelot, with the king dead but the quest continuing. Unfortunately the pace is more like Bresson than like Malory.

Smiley’s fitting opponent is Karla, the KGB’s chief of operations. Smiley has Karla’s photograph hanging in his office, just as Montgomery had Rommel’s photograph hanging in his caravan. Karla, who made a fleeting physical appearance in the previous novel, is kept offstage in this one—a sound move, since like Moriarty he is too abstract a figure to survive examination. But the tone of voice in which le Carré talks about the epic mental battle between Smiley and Karla is too sublime to be anything but ridiculous. “For nobody, not even Martello, quite dared to challenge Smiley’s authority.” In just such a way T.E. Lawrence used to write about himself. As he entered the tent, sheiks fell silent, stunned by his charisma.

There was a day when Smiley generated less of a nimbus. But that was a day when le Carré was more concerned with stripping down the mystique of his subject than with building it up. In his early novels le Carré told the truth about Britain’s declining influence. In the later novels, the influence having declined even further, his impulse has altered. The slide into destitution has become a planned retreat, with Smiley masterfully in charge. On le Carré’s own admission, Smiley has always been the author’s fantasy about himself—a Billy Batson who never has to say “Shazam!” because inside he never stops being Captain Marvel. But lately Smiley has also become the author’s fantasy about his beleaguered homeland.

The Honourable Schoolboy makes a great show of being realistic about Britain’s plight and the consequently restricted scope of Circus activities. Hong Kong, the one remaining colony, is the only forward base of operations left. There is no money to spend. Nevertheless the Circus can hope to make up in cunning—Smiley’s cunning—for what it lacks in physical resources. A comforting thought, but probably deceptive.

In the previous novel the Philby affair was portrayed as a battle of wits between the KGB and the Circus. It was the Great Game: Mrs. Philby’s little boy Kim had obvious affinities with Kipling’s child prodigy. But the facts of the matter, as far as we know them, suggest that whatever the degree of Philby’s wit, it was the Secret Service’s witlessness which allowed him to last so long. Similarly, in the latest book, the reader is bound to be wryly amused by the marathon scenes in which the legendary codebreaker Connie (back to bore us again) works wonders of deduction among her dusty filing cabinets. It has only been a few months since it was revealed that the real-life Secret Service, faced with the problem of sorting out two different political figures who happened to share the same name, busily compiled an enormous dossier on the wrong one.

There is always the possibility that in those of its activities which do not come to light the Secret Service functions with devilish efficiency. But those activities which do come to light seem usually on a par with the CIA’s schemes to assassinate Castro by poisoning his cap or setting fire to his bread. Our Man in Havana was probably the book which came closest to the truth.

This novel still displays enough of le Carré’s earlier virtues to remind us that he is not summarily to be written off. There is an absorbing meeting in a sound-proof room, with Smiley plausibly outwitting the civil servants and politicians. Such internecine warfare, to which most of the energy of any secret organization must necessarily be devoted, is le Carré’s best subject: he is as good at it as Nigel Balchin, whose own early books—especially The Small Back Room and Darkness Falls From the Air—so precisely adumbrated the disillusioned analytical skill of le Carré’s best efforts.

But lately disillusion has given way to illusion. Outwardly aspiring to the status of literature, le Carré’s novels have inwardly declined to the novel of pulp romance. He is praised for sacrificing action to character, but ought to be dispraised, since by concentrating on personalities he succeeds only in overdrawing them, while eroding the context which used to give them their desperate authenticity. Raising le Carré to the plane of literature has helped rob him of his more enviable role as a popular writer who could take you unawares. Already working under an assumed name, le Carré ought to assume another one, sink out of sight, and run for the border of his reputation. There might still be time to get away.

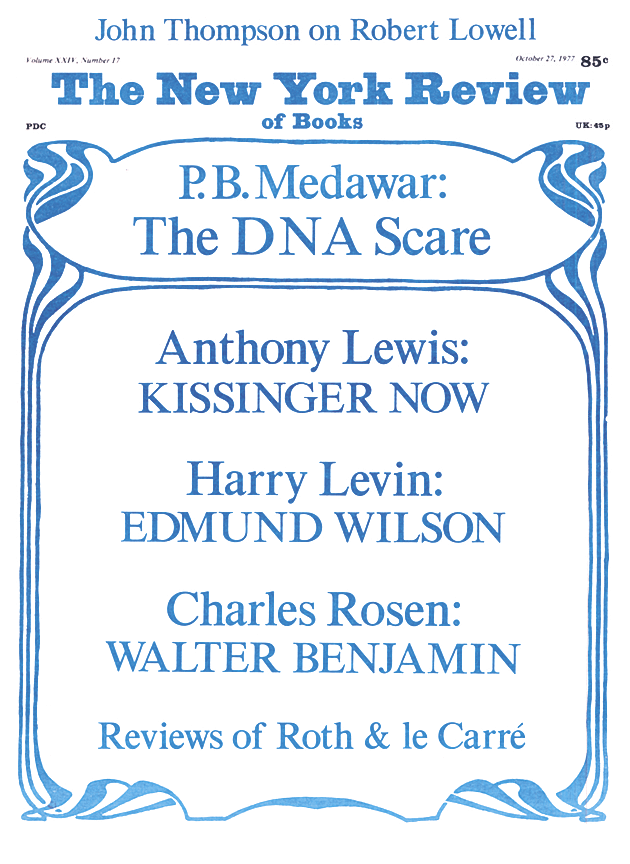

This Issue

October 27, 1977