In response to:

A Hard Case from the November 24, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

As Garry Wills observes, hard cases may make bad law. In his brief for the prosecution of Daniel Schorr (NYR, November 24), he has indeed proposed bad law. It would, in the end, virtually outlaw investigative journalism.

The key passage in Wills deserves repeating in full:

In other words, it was no longer a question of government suppression or of network cowardice. Instead Schorr was facing a problem journalists encounter all the time, possession of a juicy bit of information they cannot, for some reason, use—the publisher will not carry it for legal reasons, or for reasons of taste; from different judgments of newsworthiness, fear of an advertiser’s wrath, or whatever. In those circumstances, a free-lance writer can try to use the material elsewhere; but the writer contracted to one outlet must normally save the item for dinner table chatter, for bargaining with others to find new things, or for the memoirs he hopes to write someday when sources and contract are no longer binding.

Wills here is assuming what he denies elsewhere, that news is a commodity—like cotton, say—whose owner is at liberty to sell it or burn it as he sees fit. The owner is the plantation master, and the cotton is his whether it is picked by a salaried hand or a tenant.

I submit that news is not such a commodity, but rather something that is in the public domain. To be sure, a salaried reporter owes to his employer first crack at the information he gathers, and the talent with which he may deliver it. But nothing gives the employer a right to suppress such information indefinitely. He has bought the time and talent of the reporter during working hours, and nothing more.

(The right of the free lance is weaker, not stronger. If he sells an article to a publication that chooses not to print it, he is helpless. Writers now are seeking a model contract under which the property would revert to the author if unpublished for a year.)

By Wills’s account, Schorr did give his employer first use of his time and talent in regard to the Pike committee report on the CIA, and then sought a publisher for the text. Wills goes further, I think, than even CBS would in arguing that Schorr had no right to do so.

He surely goes further than any purveyor of news would in proposing also that the right of a reporter to protect his news sources is a “liberal shibboleth” which journalists should re-examine.

This would of course go far toward destroying investigative reporting—a trade that, contrary to conservative mythology, is constantly faced with enormous handicaps and resistance as it is.

Early on, Wills makes plain that he detests television journalists in general and Schorr in particular. As a print reporter, I too have found many of the electronic hams a pain in the neck. But I think Schorr has done us proud. He deserved better than this savage and loaded attack.

John L. Hess

New York City

Garry Wills replies:

Mr. Schorr admits that CBS did not “suppress” any newsworthy information in the Pike report. The network made a (probably wise) commercial decision not to publish the whole report. If a publisher rejects one of my manuscripts, it is not violating the First Amendment.

Bob Woodward, who presumably knows something about investigative reporting, was harsher than I in his strictures on Schorr’s performance (Washington Post “Book World,” November 13, 1977). Such reporting may involve uncovering sources, one’s own or another reporter’s—e.g., Charles Colson’s leak (to Life’s Bill Lambert) of material smearing Senator Tydings. In the Idaho case just reviewed by the Supreme Court, a fired policeman seeking reinstatement called for the name of a “police expert” who called him unfit. One should have a chance to face one’s accuser and establish the qualifications of the “expert” who damns one. Otherwise, Hunt and Colson, manufacturing cables and leaks, can defame others with impunity. Absolute protection of sources could become a gag rule making for manipulation of the press. Remember the Hitchcock movie: a man admits to murder so he can invoke the “seal of confession” and prevent a priest from testifying to what he saw. A “seal of leaking” works to protect bureaucratic gamesmen like Richard Perle—not, necessarily, to protect the public or its right to know.

I do not agree with Renata Adler that all sources have to be revealed (NYR, December 8). But if I had to choose between mistaken simplisms—always with Ms. Adler or never with Mr. Hess—I would take the former course.

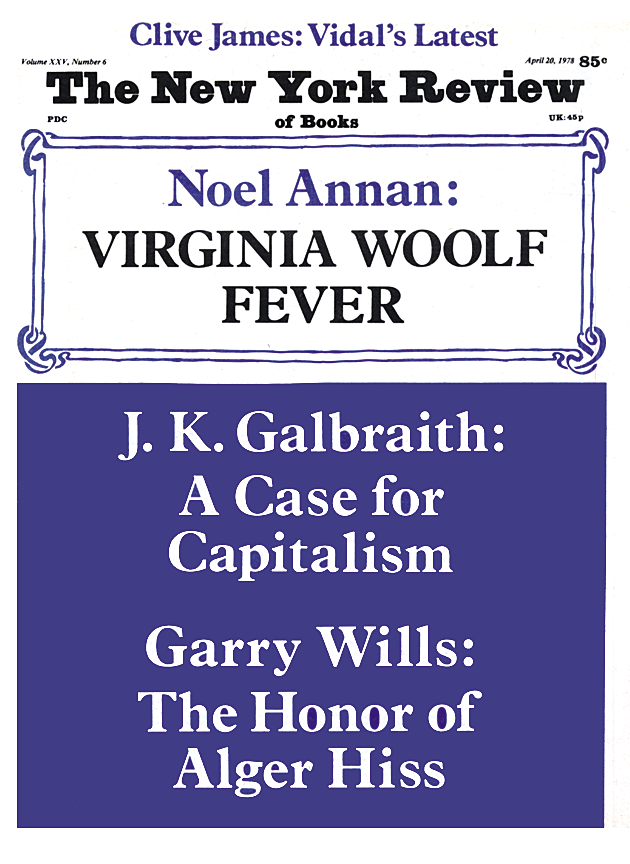

This Issue

April 20, 1978