In America in Vietnam Guenter Lewy, a political scientist, attempts to exculpate American wrongdoing in Vietnam. Oddly enough, he also provides an extremely comprehensive and damning catalogue of the physical destruction, especially of civilians, caused by American firepower. Nevertheless, he provides legal absolution for most of the killing—which may be a comfort to the policy-makers who ran the war and those who would like a freer hand to plan such “interventions” in the future. Lewy’s absolution will be little comfort to the millions of victims.

Put simply, Lewy’s argument suggests that the members of the NLF were the only Vietnamese in all of Vietnam who had no home towns. Where they were born, where they grew up, and were they came from when the fighting started in earnest during the early 1960s he does not say. He seems to believe that the NLF had little or nothing whatever to do with Vietnam, or with the Vietnamese.

“It first should be recognized,” he writes, “that the VC’s practice of ‘clutching the people to their breast’ and of converting hamlets into fortified strongholds was one of the main reasons for the occurrence of combat in populated areas.” Elsewhere he makes the same point. “The enemy liked to make the villages and hamlets a battlefield because in the open valleys and coastal lowlands the villages contained much natural cover and concealment,” he writes. “The hamlets also offered the VC a source of labor for the building of fortifications, their spread-out arrangement afforded avenues of escape, and, lastly, the VC knew that the Americans did not like to fire upon populated areas.”

This statement is nonsense. It suggests that the association between the NLF and the villages, hamlets, and their people was purely tactical and that it was initiated by the NLF from that strange, unnamed place where, presumably, the NLF had been lurking until the fighting started. It denies the facts that the NLF was composed of people from the villages, and that—as he recognizes elsewhere—they were often identical with the village populations. His account also denies the fact that the NLF were fighting in the villages because that was where their homes were. His discussion here brings to mind one of the slang expressions current among journalists and diplomats in Saigon in the late Sixties and early Seventies. We called the two opposing sides “us” and “the home team.” The basic truth of these words was not in dispute then and nothing Lewy says here contradicts it now.

Just as he provides much evidence of deliberate destruction by the US while trying to make a legal defense for it, he also contradicts his own claim that Americans “did not like to fire upon populated areas.” He writes:

Most military commanders during Westmoreland’s tenure as COMUSMACV felt they had no choice but to meet the enemy head-on wherever they encountered him. In a message to Washington, written on 30 December 1967 and addressing the problem of civilian war casualties, Ambassador Bunker expressed the same idea. The savage fighting in the villages was unavoidable, he wrote. We had to combat the enemy where we found him—in the houses and hamlets—the terrain which the VC had chosen for battle.

Sharpening this point, he writes that “by carrying the war into the hamlets and by failing properly to identify their combatants, the VC exposed the civilian population to grave harm.” Thus, the blame again seems to be placed on the NLF for fighting in the places where they lived, and not elsewhere.

Lewy carries this blame further when he finally makes a connection between the VC and the inhabitants of the villages. “Another source of confusion in judging the matter of civilian casualties,” he writes, “was the designation by many critics of all villagers as innocent civilians. We know that on occasion in Vietnam women and children placed mines and booby traps, and that villagers of all ages and sexes, willingly or under duress, served as porters, built fortifications, or engaged in other acts helping the communist forces.” Thus, the Vietnamese village population and the NLF, whom Lewy formerly set far apart, now begin to blend together. And, as he shows, they paid a price for this.

“It is well established,” he writes, in one of his summaries of international law and the law of war, “that once civilians act as support personnel they cease to be noncombatants and are subject to attack…. Here again we see the unfortunate consequence of the fact that the VC chose to fight from within villages and hamlets which provided useful cover, avenues of escape, and a source of labor for the building of fortifications. Inevitably, the civilian population was involved in the fighting.”

They were, but not for the fanciful reasons Lewy suggests. They became involved in the fighting, especially before the intervention of American firepower, because the cohesion between them and the NLF, throughout most of the rural areas of the country, was intolerable to American policy-makers. The NLF were not an independent fighting force, as Lewy tries to portray them, who, once the large-scale fighting began—which is to say when Americans intervened—elected to go to the villages. They were the governors of vast numbers of people who supported them. Undoubtedly, they were supported with varying degrees of enthusiasm and in some places they were opposed. But those millions of people did not carry out an insurrection against the NLF government—as the NLF did against the Saigon regime. It was that political connection which was intolerable to American policy-makers. 1 For most of the rural people the NLF had acquired authority through the political process they had organized while opposing the French colonial rulers and their successors. America set about dismantling the connection between the NLF and the village populations through firepower.2

Advertisement

Lewy lays the groundwork for the legality of attacking Vietnamese peasants by his assertion that the law denies them a noncombatant status once they act as “support personnel”—although most citizens of most countries could be so described if they take part in their society. Lewy finds these peasants guilty. “If guerrillas live and operate among the people like fish in the water,” he writes, “then, legally, the entire school of fish may become a legitimate military target. In such a case, the moral blame, too, would appear to fall on those who have enlarged the potential area of civilian death and damage.”

It would appear that it is only a question of degree who was more to blame for their own deaths—the NLF military forces or the Vietnamese people themselves who lived in those parts of South Vietnam, once most of the country, where the NLF was the only government. But one wonders if Lewy considers that question to have been of great concern to the victims or the maimed survivors. Earlier, when discussing the mistreatment of prisoners, he writes, “the South Vietnamese generally were reputed to have a low regard for human life and suffering.”

Perhaps one should be grateful to Lewy for providing so much evidence to prove that the target of American firepower was in fact a large part of Vietnamese society. His claims are strong ones. “It is incontrovertible,” he writes, “that the allied military effort in Vietnam was characterized by the lavish use of firepower and caused much destruction of property and a large number of civilian casualties.” And he goes on:

The fact that the discrepancy between the number of weapons captured and the number of VC/NVA reported killed was generally most pronounced in areas of combat with a high population density such as the coastal provinces and the Delta suggests that the number of villagers included in the body count was indeed substantial.

Other examples show not only how much damage was done but how aware of it prominent American leaders were. Lewy quotes a statement made in 1972, the year of his death, by John Paul Vann, the legendary US expert on “counter-insurgency.”

In the last decade, I have walked through hundreds of hamlets that have been destroyed in the course of a battle, the majority as the result of the heavier friendly fires. The overwhelming majority of hamlets thus destroyed failed to yield sufficient evidence of damage to the enemy to justify the destruction of the hamlet. Indeed, it has not been unusual to have a hamlet destroyed and find absolutely no evidence of damage to the enemy. I recall in May 1969 the destruction and burning by air strike of 900 houses in a hamlet in Chau Doc Province without evidence of a single enemy being killed…. The destruction of a hamlet by friendly firepower is an event that will always be remembered and practically never forgiven by those members of the population who lost their homes.

Elsewhere, after quoting several admonitions from commanders to exercise care in firing on populated areas, Lewy writes: “Indeed, the constantly repeated expressions of intense concern of MACV with the question of civilian casualties can be read as an acknowledgment that rules aimed at protecting civilian life and property were, for a variety of reasons, not applied and enforced as they should have been.”

Much of the violence had a specific purpose—as Lewy makes clear. If the problem was the political connection between the people in the villages and the NLF, then military force was applied to destroy that connection and separate these people from the NLF. The best way of separating the people from their society was to force them to flee—to make them refugees. Lewy himself explains how this was a deliberate policy of the American policy-makers: “…the largest single factor explaining the influx of refugees was the stepped-up tempo and intensity of the war.” Contrary to the claims of embassy officials at the time, these people were not “voting with their feet.” Lewy cites a study done by the army chief of staff in 1966 which said that “US-RVNAF bombing and artillery fire, in conjunction with ground operations, are the immediate and prime causes of refugee movement into GVN-controlled urban and coastal areas.” He also quotes a suggestion made to Lyndon Johnson in April, 1967, by Robert Komer, when Komer was about to depart for Saigon to manage the “pacification” program. Komer wanted the command “to step up refugee programs deliberately aimed at depriving the VC of a recruiting base.”

Advertisement

Komer’s suggestion only reflected a policy that was already established. Lewy quotes a 1966 cable from the State Department to the Saigon embassy urging that military operations and refugee flow be coordinated.

This helps deny recruits, food producers, porters, etc. to VC, and clears battlefield of innocent civilians. Indeed, in some cases we might suggest military operations specifically designed to generate refugees—very temporary or longer term depending on local weighing of our interests and capacity to handle them well. Measures to encourage refugee flow might be targeted where they hurt the VC most and embitter people toward US/GVN forces least [emphasis added].

The internal contradictions of that cable are interesting. On the one hand the writer suggests the need for violent military operations against populated areas inhabited by innocent civilians; but he was still able to state that such actions clear the “battlefield of innocent civilians.” Perhaps Under Secretary of State Nicholas Katzenbach had this contradiction in mind when, in June 1967, he urged Johnson “to stimulate a greater refugee flow through psychological inducements to further decrease the enemy’s manpower base.” Undoubtedly, “psychological inducements” such as leaflets or broadcasts seemed a good idea in Washington. But for the most part the American command relied upon the psychological effect of strong doses of napalm, white phosphorous, and antipersonnel weapons to encourage people to move.

Clearly Lewy does not want to be accused of ignoring American brutality. He sometimes sounds as if he became desperate and distracted while culling the mountain of evidence before him. “The record of ‘dramatic misconduct,’ ” he writes, “included running Vietnamese cyclists and pedestrians off the road; hitting Vietnamese with rocks and cans; firing into hamlets from convoys without cause on pretext of having heard sniper fire; joy-killing of water buffalo and cattle; raping Vietnamese girls; being drunk, disorderly and obnoxious; and much more.” What, one wonders, did being “obnoxious” mean in this context? Did the soldiers fail to knock before entering? What, for that matter, does “and much more” mean?

Still, in the face of such evidence, Lewy tries to exonerate America from legal culpability for what happened in Vietnam. “There was much in the American military effort in Vietnam that was legal but should probably not have happened,” he writes. That statement alone suggests the uselessness of his argument. The various precedents he cites from the “laws of war,” and his manipulation of them, evoke a lawyer well versed in loopholes attempting to regain a license for a client even though the misbehavior for which the license was revoked has been openly acknowledged. Richard Wasserstrom, professor of law and philosophy at the University of California, discussed the same laws of war in his review of Telford Taylor’s Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy (NYR, June 3, 1971), and his conclusions apply to Lewy’s use of those laws. They are, Wasserstrom wrote, “not of much importance morally and…they are not morally admirable inventions…. When we look at the rules which tell us what may and may not be done in time of war, they do not correspond in any obvious way to intelligible moral behavior.”

Lewy seems to admit as much himself. “In the final analysis, of course, law alone, no matter how comprehensive and carefully phrased, cannot assure protection of basic human values,” he writes. “Hugo Grotius, the father of modern international law, quoted with approval the advice which Euripides in The Trojan Women put into the mouth of Agamemnon addressing Pyrrhus: ‘What the law does not forbid, then let shame forbid.’ This counsel retains its moral worth.”

It does, but one finds little application of it in Lewy’s book. His nod toward a sense of what should or should not happen in war, as opposed to what is “legal,” brings to mind the old army maxim that it is always important to “cover your ass.” His attention to Grotius’s warning is as perfunctory as the respect for law was among Americans in Vietnam. To be sure, there were all sorts of rules of engagement concerning noncombatants, prisoners, etc., and, officially, limits on what could be done. But in practice these were often ignored without fear of prosecution, or followed only by going through the motions. I recall a firefight in a rubber plantation near the Cambodian border in late 1968 when American troops had cornered an NVA soldier. He was probably wounded, though no one could be sure, and he had taken cover in a shallow foxhole. There was no fire coming from the hole. As the American officer explained, he was under orders to take prisoners alive.

“Tell him to chieu hoi,” he shouted to the ARVN interpreter with the unit, using the Vietnamese expression for “rallying” to the government side, or, in other words, surrendering. The ARVN interpreter, whose helmet was adorned with the motto “Make Love Not War,” raised his head from the earth slightly and muttered, almost inaudibly, though he was only a few feet from me and the hole was ten yards away, “chieu hoi.”

“OK, frag him,” the officer shouted, now that form had been observed. An American soldier dropped several grenades into the hole and the unit moved on.

Certainly there were rules that, had they been followed, might have spared civilian lives. In fact most American soldiers were undoubtedly made more aware of the need for high body counts than they were of the subtleties Lewy discusses. In my own conversations with troops of the Ninth Division, which fought with devastating results in the heavily populated delta region, I found few soldiers who knew much about the rules of engagement or were concerned to carry them out. But many hootches at the base camp at Dong Tam were adorned with the motto: “Death Is Our Business and Business Is Good.”

Rather than to Euripides Lewy is drawn to the work of Hersh Lauterpacht, a British jurist. “As to ‘imperative military reasons,’ ” Lewy writes,

the principle of military necessity allows a belligerent to take all measures not forbidden by international law that are necessary for the defeat of the opponent in the least possible time and at the least cost to himself. Applying this principle, the relocation of Vietnamese civilians in order to deprive the VC of their support does not seem unreasonable. An eminent British authority, Professor Hersh Lauterpacht, grants the occupying power even the right to “general devastation” in cases, “when, after the defeat of his main forces and occupation of his territory, an enemy disperses his remaining forces into small bands which carry on guerrilla tactics and receive food and information, so that there is no hope of ending the war except by general devastation which cuts the supplies of every kind from the guerrilla bands.” [Emphasis added]

“General devastation” seems rather a large “grant” of authority for Lauterpacht to have made to Guenter Lewy, let alone the US armed forces. But this free-floating license to devastate is the key to much of Lewy’s discussion of “law.” Again and again he tries to show that much atrocious behavior can be made to fit within the loose doctrines expounded in treatises such as Lauterpacht’s instead of asking what shameful acts should have been prohibited.

His discussion of free-fire zones is especially apt in this respect. Because, as Lewy points out, that term “conveyed the connotation of uncontrolled and indiscriminate firing,” it was changed to “specified strike zone.” These “SSZs,” according to a military directive Lewy cites, were supposed to be “configured to eliminate populated areas except those in accepted VC bases.” But, as Lewy acknowledges, for a long time most VC bases and populated areas were virtually identical. “Since the definition of an SSZ included the assumption that it contained no friendly civilians,” he continues,

the implementation of command concern for noncombatants clearly was difficult. Westmoreland had exhorted his commanders that “the Vietnamese populace must be presumed to be friendly until it demonstrates otherwise,” yet in the SSZ this presumption was reversed. It was therefore faultless logic which made the commanding general of US Army units in Vietnam in 1969 conclude that the probability of killing or injuring innocent civilians in hamlets situated in SSZs is zero, by definition.

Thus one can understand the simple bewilderment of the Marine commander at Cam Ne, the village where a CBS television team including Morley Safer filmed Marines setting fire to houses. “It is extremely difficult for a ground commander to reconcile his tactical mission and a people-to-people program,” Lewy reports the officer as saying.

Lewy could only agree. “Unhappy with life in the refugee camps or out of sympathy with the VC,” he writes,

many villagers drifted back into or remained in areas declared SSZs. Hence, when allied troops carried out ground operations or air strikes in these zones civilians were still being killed or wounded. However unfortunate on humanitarian grounds and counterproductive from the point of view of pacification, it is not likely that these civilian casualties raise an issue of criminal liability as long as adequate notice of the designation of an area as an SSZ was given.

Elsewhere he comments, “The requirements of the law of war could be considered satisfied if there existed ROE [rules of engagement] incorporating applicable provisions of the law of war and the American command made a credible effort to make known and enforce these rules.” Translated from the officialese in which Lewy writes, these statements say that the obliteration of innocent people in their homes was wrong, terrible, and self-defeating, but that those who ordered it could still put up a narrow legal defense in a court-martial that will never be held. It would, by the way, be a largely bogus defense, as those who observed the “efforts” to give “adequate notice” could testify.

In his search for exoneration Lewy can sound, word for word, like the press releases they used to hand out at the embassy in Saigon. “American aid programs,” he writes, “contributed substantially to the improvement of public health and the availability of medical care.” Any reporter could see this was true; but it was equally true that the American presence contributed far more to the need for medical care than it did to its availability. He goes on to say that “whatever the shortcomings of the American medical aid program, it surely does not fit into any kind of scheme to destroy the Vietnamese people. If we add to all this the various aid programs aiming at improving the technological and economic development of South Vietnam, it becomes understandable why the cumulative impact of the American presence was a substantial rise in the standard of living and a consequent population increase.”

Vietnam thus becomes for Lewy a magical world where the crude and contradictory abstractions of the political scientist—e.g., “general devastation” and a “rise in the standard of living”—can happily coexist. They have to, if Lewy is finally to reach his conclusion:

An acceptance of the simplistic slogan “No More Vietnams” not only may encourage international disorder, but could mean abandoning basic American values.

This is the point Lewy has evidently been working up to throughout his book—a point that he might reasonably have expected would be welcomed among the frustrated American strategists who have been kept out of action in recent years. But this outcome may be doubted. The unfortunate Lewy, trying so hard to defend our war as lawful, has unwittingly written one of the most damning indictments yet of the American intervention in Vietnam.

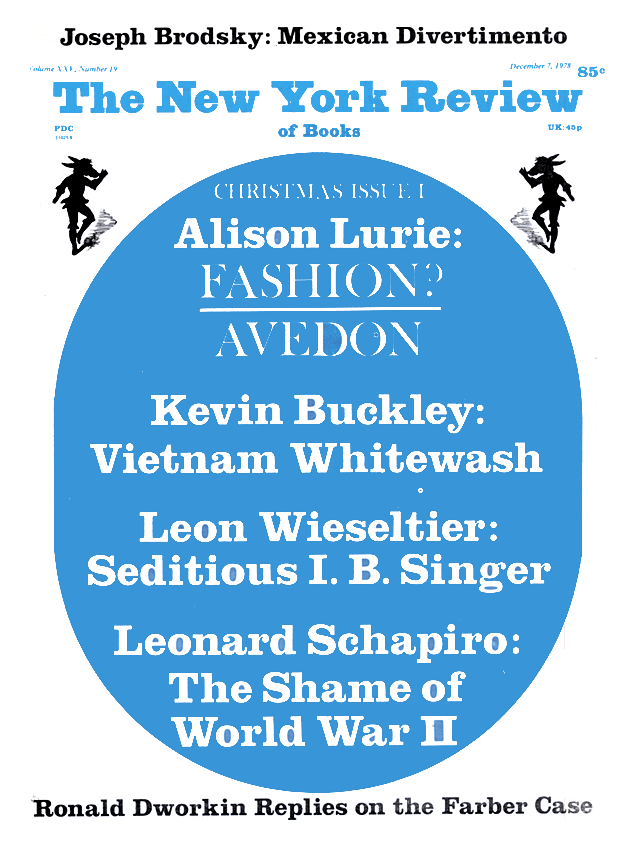

This Issue

December 7, 1978

-

1

It was a political connection of long standing. Discussing why the 1956 elections called for by the Geneva Agreement of 1954 were never held in South Vietnam, Ho Thong Minh, a former minister of defense under Ngo Dinh Diem, and predictably critical of the NLF, said, “In the main, though, the population was probably going to vote in favor of the Communists.” His statement appears in a collection of interviews compiled by Michael Charlton and Anthony Moncrieff of the BBC, to be published as Many Reasons Why by Hill and Wang in January, 1979. ↩

-

2

For a firsthand account of how the NLF governed with popular support in the rural areas, see Reaching the Other Side (Crown, 1978), by Earl Martin, a Mennonite missionary who spent five years in Quang Ngai province. ↩