Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

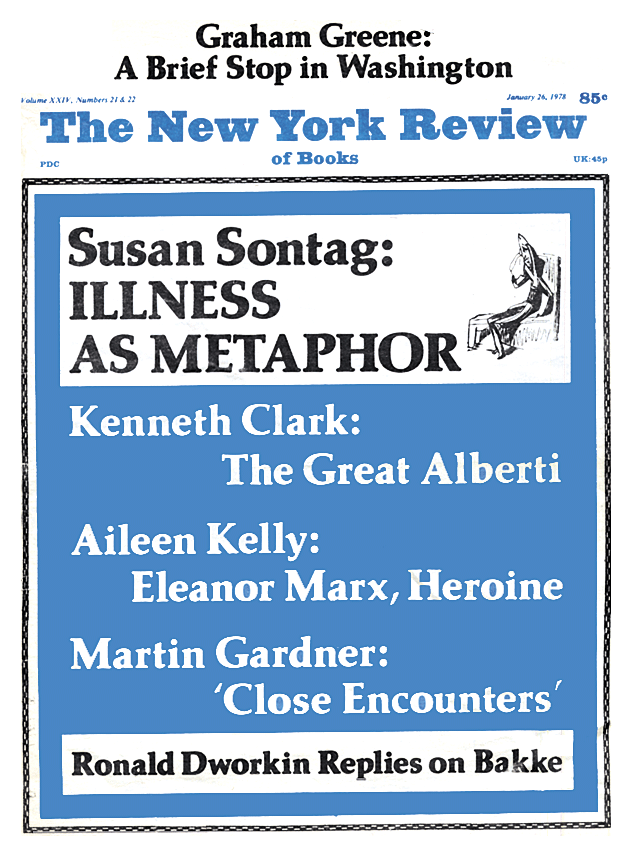

I want to describe not what it’s really like to emigrate to the kingdom of the ill and to live there, but the punitive or sentimental fantasies concocted about that situation; not real geography but stereotypes of national character. My subject is not physical illness itself but the uses of illness as a figure or metaphor. My point is that illness is not a metaphor, and that the most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking. Yet it is hardly possible to take up one’s residence in the kingdom of the ill unprejudiced by the lurid metaphors with which it has been landscaped. It is toward an elucidation of those metaphors, and a liberation from them, that I dedicate this inquiry.

I

Two diseases have been spectacularly, and similarly, encumbered by the trappings of metaphor: tuberculosis and cancer.

The fantasies inspired by TB in the last century, by cancer now, are first of all responses to a disease thought to be intractable and capricious—that is, a disease not understood—in an era in which medicine’s central premise is that all diseases can be cured. Such a disease is, by definition, mysterious. For as long as what causes TB was not understood and the ministrations of doctors remained so ineffective, TB was thought to be an insidious, implacable theft of a life. Now it is cancer’s turn to be the disease that doesn’t knock first before it enters, cancer that fills the role of an illness experienced as a ruthless, secret invasion—a role it will keep until, one day, its etiology is as clear and its treatment as efficacious as those of TB have become.

Although the way in which disease mystifies us is grounded in new expectations, the disease itself (once TB, now cancer) arouses thoroughly old-fashioned kinds of dread. Any disease that is treated as a mystery and acutely enough feared will be felt to be morally, if not literally, contagious. Thus a surprisingly large number of people with cancer find themselves being shunned by relatives and friends and are the object of practices of decontamination by members of their household, as if cancer, like TB, were an infectious disease. Contact with someone afflicted with a disease regarded as a mysterious malevolency inevitably feels like a trespass; worse, like the violation of a taboo. The very names of such diseases are felt to have a magic power. In Stendhal’s Armance (1827), the hero’s mother refuses to say “tuberculosis” for fear that pronouncing the word will hasten the course of her son’s malady. And Karl Menninger has observed (in The Vital Balance) that “the very word ‘cancer’ is said to kill some patients who would not have succumbed (so quickly) to the malignancy from which they suffer.” His observation is offered in support of anti-intellectual pieties and facile compassion all too triumphant in contemporary medicine and psychiatry: “Patients who consult us because of their suffering and their distress and their disability have every right to resent being plastered with a damning index tab.” Dr. Menninger recommends that physicians generally abandon “names” and “labels”—which would mean, in effect, increasing secretiveness and medical paternalism. It is not naming as such that is pejorative or damning but the name “cancer.” As long as a particular disease is treated as an evil, invincible predator, not just a disease, most people with cancer will indeed be demoralized by learning what disease they have. The solution is hardly to stop telling cancer patients the truth but to rectify the conception of the disease, to de-mythicize it.

When, not so many decades ago, learning that one had TB was tantamount to hearing a sentence of death—as today, in the popular imagination, cancer equals death—a tremendous fear surrounded TB, and it was common to conceal the identity of their disease from tuberculars and, after their death, from their children. Even with patients informed about their disease, doctors and family were reluctant to talk freely. “Verbally I don’t learn anything definite,” Kafka wrote to a friend in April 1924 from the sanatorium where he died two months later, “since in discussing tuberculosis…everybody drops into a shy, evasive, glassy-eyed manner of speech.”

The fear surrounding cancer being even more acute, so is the concealment. In France and Italy it is still the rule for doctors to communicate a cancer diagnosis to the patient’s family but not to the patient; doctors consider that the truth will be intolerable to all but exceptionally mature and intelligent patients. (A leading French oncologist has told me that fewer than a tenth of his patients know they have cancer.) In America, where—in part because of the doctors’ fear of malpractice suits—there is now much more candor with patients, the country’s largest cancer hospital mails routine communications and bills to out-patients in envelopes that do not reveal the sender, on the assumption that the illness may be a secret from their families. Since getting cancer can be a scandal that jeopardizes one’s love life, one’s chance of promotion, one’s very job, patients who know what they have tend themselves to be extremely prudish, if not outright secretive, about their disease. And a federal law, the 1966 Freedom of Information Act, cites “treatment for cancer” in a general clause exempting from disclosure matters that constitute “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” It is the only disease mentioned.

Advertisement

The amount of lying to and by cancer patients is, in part, a reflection of the modern attitude toward death. As dying has come to be regarded in advanced industrial societies as a shameful, unnatural event, so that disease which is widely considered a synonym for death has come to seem shameful, something to deny. The policy of hiding or equivocating about the nature of their disease to cancer patients reflects the conviction that dying people are best spared the news that they are dying, and that the good death is the split-second one, or the one that happens while we’re unconscious or asleep. Still, the denial of death does not explain the extent of the lying and the wish to be lied to, doesn’t touch the deepest dread. Someone who has had a coronary is at least as likely to die of another one within a few years as someone with cancer is likely to die soon from cancer. But no one thinks of concealing the truth from a cardiac patient: there is nothing shameful about a heart attack. Cancer patients are lied to not just because the disease is (or is thought to be) a death sentence but because it is felt to be obscene—in the original meaning of that word: illomened, abominable, disgusting, offensive to the senses. Cardiac disease implies a weakness, trouble, failure that is mechanical; there is no scandal, it has nothing of the taboo that once surrounded people afflicted with TB and still surrounds those who have cancer. The metaphors attached to TB and to cancer imply living processes of a particularly resonant and horrid kind.

II

Throughout most of their history, the metaphoric uses of TB and cancer criss-cross and overlap. The Oxford English Dictionary records “consumption” in use as a synonym for pulmonary tuberculosis as early as 1398. (John of Trevisa: “Whan the blode is made thynne, soo folowyth consumpcyon and wastyng.”)1 But the pre-modern understanding of cancer also invokes the notion of consumption. The OED gives as the earliest general definition of cancer: “anything that frets, corrodes, corrupts, or consumes slowly and secretly.” (Thomas Paynel in 1528: “A canker is a melancolye impostume, eatynge partes of the bodye.”) Conversely, the earliest literal definition of cancer—from the Greek karkínos and the Latin cancer, both meaning crab—is a growth, lump, or protuberance. (Hence the disease’s name, inspired by the resemblance of the swollen veins surrounding an external tumor to a crab’s legs; not, as many people think, because a metastatic disease crawls or creeps like a crab.) And etymology indicates that tuberculosis—from the Latin tuber, meaning bump, swelling—was also once considered a type of abnormal extrusion; the word tuberculosis means a morbid swelling, protuberance, projection, or growth.2 Rudolf Virchow, who founded the science of cellular pathology in the 1850s, thought of the tubercle as a tumor.

Thus, throughout its premodern history, tuberculosis was—typologically—cancer. And cancer was described as a process, like TB, in which the body was consumed. The conceptions of the two diseases as we inherit them today could not be set until the advent of cellular pathology. Only with the microscope was it possible to grasp the distinctiveness of cancer, as a type of cellular activity, and to understand that the disease did not always take the form of an external or even palpable tumor. (Before the nineteenth century nobody could have identified leukemia as a form of cancer.) And it was not possible definitively to separate cancer from TB until the 1880s, when the germ theory of TB became established in medical thinking. It was then that the leading metaphors of the two diseases became truly distinct and, for the most part, contrasting. And it was about then that the modern fantasy about cancer began to take shape—a fantasy which from the 1920s on would inherit the scope of and most of the problems dramatized by the fantasies about TB, but with the two diseases and their symptomology imagined and identified in quite different—indeed, almost opposing—ways.

Advertisement

TB is understood as a disease of one organ, the lungs, while cancer is understood as a system-wide disease. TB is understood as a disease of extreme contrasts: white pallor and red flush, vitality alternating with languidness. The spasmodic evolution of the disease is illustrated by what is thought of as the prototypical TB symptom, coughing. The sufferer is wracked by coughs, then sinks back, recovers breath, breathes normally. Then coughs again. In contrast, cancer is a disease of growth (sometimes visible; more characteristically, inside), of abnormal, ultimately lethal growth that is measured, incessant, steady. Although there may be periods in which tumor growth is arrested (remissions), cancer produces no contrasts like the oxymorons of behavior—febrile activity, hectic inactivity, passionate resignation—thought to be typical of TB, nothing comparable to TB’s paradoxical symptoms: liveliness that comes from enervation, rosy cheeks that look like a sign of health but come from fever. The tubercular is pallid some of the time; the pallor of the cancer patient doesn’t change.

TB makes the body transparent. The X-rays which are the standard diagnostic tool permit one, often for the first time, to see one’s insides—to become transparent to oneself. While TB is understood to be, from early on, a disease rich in visible symptoms (progressive emaciation, coughing, languidness, fever), and can be suddenly and dramatically revealed (the blood on the handkerchief), in cancer the main symptoms are thought to be, characteristically, invisible—until the last stage, when it is too late. Generally one doesn’t know one has cancer. The disease is often discovered by chance or through a routine medical check-up, and can be far advanced without exhibiting any appreciable symptoms. The patient has an opaque body that must be taken to a specialist to find out if it contains cancer. What the patient cannot perceive the specialist will determine by analyzing tissues taken from the body. TB patients may see their X-rays or even possess them: the patients at the sanatorium in The Magic Mountain carry theirs around in their breast pockets. Cancer patients don’t look at their biopsies.

Euphoria, increased appetite, exacerbated sexual desire were—still are—thought to be characteristic of TB. Part of the regimen for patients in The Magic Mountain is a second breakfast, eaten with gusto. Having TB was thought to be an aphrodisiac. Cancer is thought to be de-sexualizing. But it is characteristic of TB that many of its symptoms are deceptive, that what looks like an increase of vitality is really a sign of death. Cancer has only true symptoms.

Though the course of both diseases is generally marked by a loss of weight, getting thin from TB is understood very differently from getting thin from cancer. In TB, the person is “consumed,” burned up. In cancer, the patient is “invaded” by alien cells, which multiply or proliferate, causing an atrophy or blockage of body functions. The cancer patient “shrivels” (Alice James’s word) or “shrinks” (Wilhelm Reich’s word).

TB is disintegration, febrilization; it is a disease of liquids—the body turning to phlegm and mucus and sputum and, finally, blood—and of air, of the need for better air. Cancer is something hard: the body tissues degenerating, turning to stone. Alice James, writing in her journal a year before she died from cancer in 1892, speaks of “this unholy granite substance in my breast.” But this lump is alive, a fetus with its own will. Novalis, in an entry written around 1798 for his encyclopedia project, defines cancer, along with gangrene, as “full-fledged parasites—they grow, are engendered, engender, have their structure, secrete, eat.” Cancer is a demonic pregnancy. St. Jerome must have been thinking of a cancer when he wrote: “The one there with his swollen belly is pregnant with his own death.” (“Alius tumenti aqualiculo mortem parturit.”)

TB is a disease of time, the fever that hastens things. TB speeds up life; highlights it; spiritualizes it. In both English and French, consumption “gallops.” Cancer has stages rather than gaits; it is “terminal.” Cancer works slowly, insidiously: the standard euphemism in obituaries is that someone has “died after a long illness.” Every characterization of cancer describes it as slow, and so it was first used metaphorically. “The word of him creepeth as a cankir” is the way Wyclif translated, in 1382, a phrase in II Timothy 2:17. (Among the earliest figurative uses of cancer are as a metaphor for “ennuie” and for “sloth.”)3 Metaphorically, cancer is not so much a disease of time as a disease or pathology of space. Its principal metaphors refer to topography (cancer “spreads” or “proliferates”; tumors are surgically “excised”) and its most dreaded consequence, short of death, is the mutilation or amputation of part of the body.

TB is often imagined as a disease of poverty and deprivation—of thin garments, thin bodies, unheated rooms, poor hygiene, inadequate food. The poverty may not be as literal as Mimi’s garret in La Bohème; the tubercular Marguerite Gautier in La Dame aux camélias lives in luxury, but inside she is a waif. In contrast, cancer is a disease of middle-class life, a disease associated with affluence, with excess. Rich countries have the highest cancer rates and the rising incidence of the disease is seen as resulting, in part, from a diet rich in fat and proteins and from the toxic effluvia of the industrial economy that creates affluence. The treatment of TB is identified with the stimulation of appetite, cancer treatment with nausea and the loss of appetite. The undernourished nourishing themselves—alas, to no avail. The overnourished, unable to eat.

The TB patient is thought to be helped—maybe even cured—by a change in environment. There was a notion that TB was a wet disease, a disease of humid and dank cities. The inside of the body became damp (“moisture in the lungs” was a favored locution) and had to be dried out. Doctors advised travel to high, dry places—the mountains, the desert. But no change of surroundings is thought to help the cancer patient. The fight is all inside one’s own body. It may be, is increasingly thought to be, something in the environment that has caused the cancer. But once cancer is present, it cannot be reversed or diminished by a move to a better (that is, less carcinogenic) environment.

TB is thought to be relatively painless. Cancer is thought to be, invariably, excruciatingly painful. TB is thought to provide an easy death, while cancer is the spectacularly awful one. For over a hundred years TB remained the preferred, edifying way of killing off a character in a novel or play—a spiritualizing, refined disease. Nineteenth-century literature is stocked with descriptions of painless, unfrightened, beatific deaths from TB, particularly of young people: of Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and of Dombey’s son Paul in Dombey and Son and of Smike in Nicholas Nickleby, where Dickens describes TB as the “dread disease” which “refines” death

of its grosser aspect…in which the struggle between soul and body is so gradual, quiet, and solemn, and the result so sure, that day by day, and grain by grain, the mortal part wastes and withers away, so that the spirit grows light and sanguine with its lightening load…. 4

Contrast these sentimental, ennobling TB deaths with the slow, agonizing cancer deaths of Eugene Gant’s father in Thomas Wolfe’s Of Time and the River and of the sister in Bergman’s film Cries and Whispers. The dying tubercular is pictured as made more beautiful and more soulful; the person dying of cancer is portrayed as robbed of all capacities of self-transcendence, humiliated by fear and agony.

Of course these contrasts are extrapolated from the popular mythology of both diseases, not from the facts. Many tuberculars died in terrible pain, while some people die of cancer feeling little or no pain up to the end. The poor and the rich get both TB and cancer; and not everyone who has TB coughs. But the mythology continues to prevail. It is not just because pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form of TB that most people think of TB, in contrast to cancer, as a disease of one organ. It is because the myths surrounding TB do not fit the brain, larynx, kidneys, long bones, and other sites where the tubercle bacillus can also settle, but do have a close fit with the traditional imagery (breath, life) associated with the lungs.

While TB takes on qualities assigned to the lungs, which are part of the upper, spiritualized body, cancer is notorious for attacking parts of the body (colon, bladder, rectum, breast, cervix, prostate, testicles) that are embarrassing to acknowledge. Having a tumor generally arouses some feelings of shame but, in the hierarchy of the body’s organs, lung cancer is felt to be less shameful than rectal cancer. (And one non-tumor form of cancer now turns up in commercial fiction in the role that TB once had, as the romantic disease which cuts off a young life. The heroine of Erich Segal’s Love Story dies of leukemia—the “white” or TB-like form of the disease, for which no mutilating surgery can be proposed—not of stomach or breast cancer.) A disease of the lungs is, metaphorically, a disease of life. Cancer, as a disease that can strike anywhere, is a disease of the body. Far from proving anything spiritual, it proves that the body is, alas, and all too much, the body.

What makes all these fantasies flourish is that both TB and cancer are thought to be much more than diseases that usually are (or were) fatal. They are identified with death itself. In Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens apostrophized TB as the

disease in which death and life are so strangely blended, that death takes the glow and hue of life, and life the gaunt and grisly form of death; disease which medicine never cured, wealth never warded off, or poverty could boast exemption from….

And Kafka wrote to Max Brod in October 1917 that he had “come to think that tuberculosis…is no special disease, or not a disease that deserves a special name, but only the germ of death itself, intensified.” Cancer inspires similar speculations. Georg Groddeck, whose remarkable views on cancer in The Book of the It (1923) anticipate those of Wilhelm Reich, wrote:

Of all the theories put forward in connection with cancer, only one has in my opinion survived the passage of time, namely, that cancer leads through definite stages to death. I mean by that that what is not fatal is not cancer. From that you may conclude that I hold out no hope of a new method of curing cancer…[only] the many cases of so-called cancer….5

For all the progress in treating cancer, many people still subscribe to Groddeck’s equation: cancer=death. Thus, to deal with the metaphors surrounding TB and cancer is to explore the idea of the morbid, in particular its evolution from the nineteenth century (when TB was the most common cause of death) to our own time (where the most dreaded disease is cancer). In the nineteenth century it was possible, through fantasies about TB, to aestheticize death. Thoreau, who himself suffered from TB, wrote in 1852: “Death and disease are often beautiful, like the hectic glow of consumption.” Nobody conceives of cancer the way TB was thought of—as a decorative, often redemptive death. Although one good poet, L. E. Sissman, while dying, wrote some excellent poems about cancer, it seems unimaginable to aestheticize the disease.

III

The most striking similarity between the myths of TB and of cancer is that both are, or were, understood as diseases of passion. With TB, the outward fever was a sign of an inward burning. The tubercular is one “consumed” or dissolved by passion, a passion leading to the dissolution of the body. First came the use of tubercular metaphors to describe love—the image of “diseased” love, of a passion that “consumes.”6 Eventually the image was inverted, and TB was conceived as a variant of the disease of love. Love is now lethal. In a heartbreaking letter of November 1, 1820, from Naples, Keats, forever separated from Fanny Brawne, writes, “If I had any chance of recovery [from tuberculosis], this passion would kill me.” As a character in The Magic Mountain explains: “Symptoms of disease are nothing but a disguised manifestation of the power of love; and all disease is only love transformed.”

As once TB was thought to come from too much passion, afflicting the reckless and sensual, today people believe that cancer is a disease of insufficient passion, an affliction of those who are sexually repressed, inhibited, unspontaneous, incapable of expressing anger. These seemingly opposite diagnoses are actually not so different versions of the same view (and deserve, in my opinion, the same amount of credence). For both accounts of a characterology associated with a given disease stress the fact of being balked, frustrated, heavy-hearted. As much as TB was celebrated as a disease of passion, it was also regarded as a disease of repression. The hero of Gide’s The Immoralist (paralleling what Gide perceived to be his own story) gets TB because he has repressed his true sexual nature. When Michel accepts Life, he recovers. With this scenario, today Michel would have to get cancer.

As cancer is understood today to be the wages of repression, so TB was once understood as the ravages of frustration. What is called a liberated sexual life is believed by some people today to stave off cancer, for pretty much the same reason that sex was often prescribed to tuberculars as a therapy. In The Wings of the Dove, Milly Theale’s doctor prescribes a love affair as a cure for her TB; and it is when she discovers that her duplicitous suitor Merton Densher is secretly engaged to her friend Kate Croy that she dies. And in his letter of November 1820, Keats exclaims: “My dear Brown, I should have had her when I was in health, and I should have remained well.”

According to the mythology of TB, there is generally some event (unhappy passion) which provokes, which expresses itself in, a bout of TB.7 But the passions must be thwarted, the hopes blighted. And the passion, although usually love, could be a political or moral passion. At the end of Turgenev’s On the Eve, Insarov, the young Bulgarian revolutionary-in-exile who is the hero of the novel, realizes that he can’t return to Bulgaria. He sickens with longing and frustration, gets TB and dies.

According to the mythology of cancer, there is generally some steady expression of feeling that causes the disease. In the earlier, more optimistic form of this fantasy, the repressed feelings were sexual; now, in a notable shift, it is the repression of violent feelings that is imagined to cause cancer. The thwarted passion that killed Insarov was idealism. The thwarted passion that people think will give them cancer if they don’t let it out is rage. There are no modern Insarovs. Instead there are cancerphobes like Norman Mailer who recently explained that had he not stabbed his wife (and acted out “a murderous nest of feelings”) he would have gotten cancer and “been dead in a few years himself.”8 It is the same fantasy that was once attached to TB, but in rather a nastier version.

The source for much of the current fancy that associates cancer with the repression of passion is Wilhelm Reich, who defines cancer as “a disease following emotional resignation—a bio-energetic shrinking, a giving up of hope.”9 But the same theory can be, and has been, applied to TB. Georg Groddeck defines TB as: “the pining to die away. The desire must die away, then, the desire for the in and out, the up and down of erotic love, which is symbolized in breathing. And with the desire the lungs die away,…the body dies away….”10

Reich illustrates his influential theory with Freud’s cancer, which, he said, began when Freud, a naturally passionate man, “had to give up, as a person. He had to give up his personal delights, in his middle years…. If my view of cancer is correct, you just give up, you resign—and, then, you shrink.”11 Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” is often cited as a case history of the link between cancer and characterological resignation.

But in the typical accounts of TB in the nineteenth century, this feature of resignation is also present. Mimi and Camille die because of their renunciation of love, beatified by resignation. An ostentatious resignation is characteristic of the rapid decline of tuberculars as reported at length in fiction. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Little Eva dies with preternatural serenity, announcing to her father a few weeks before the end: “My strength fades away every day, and I know I must go.” All we learn of Milly Theale’s death in The Wings of the Dove is that “she turned her face to the wall.”

TB sufferers may be represented as passionate but are, more characteristically, deficient in vitality, in life force. (As in the contemporary updating of this fantasy, the cancer-prone are those who are not sufficiently sensual or in touch with their anger.) This is how those two famously tough-minded observers, the Goncourt brothers, explain the TB of their friend Murger (the author of the book from which La Bohème was drawn): he is dying “for want of vitality with which to withstand suffering.” TB is celebrated as the disease of born victims, of sensitive, passive people who are not quite life-loving enough to survive. (What is hinted at by the languid, etherealized belles of Pre-Raphaelite art is made explicit in the emaciated, hollow-eyed, tubercular girls depicted by Edvard Munch.) And while the standard representation of a death from TB places the emphasis on the perfected sublimation of feeling, the recurrence of the figure of the tubercular courtesan indicates that TB was also thought to make the sufferer sexy. All these notions are recapitulated by Mann in The Magic Mountain and in his short story “Tristan.”

Like all really successful metaphors, the metaphor of TB was rich enough to provide for two contradictory applications. It described the death of someone (like a child) thought to be too “good” to be sexual, the assertion of an angelic psychology. It was also a way of describing sexual feelings, while removing the onus of libertinism. All responsibility is lifted because one is in a state of objective, physiological decadence or deliquescence. It was both a way of describing sensuality and promoting the claims of passion, and a way of describing repression and advertising the claims of sublimation. Above all, it was a way of making people “interesting.” This idea—of how interesting the sick are—was given its subtlest and most influential formulation by Nietzsche in The Will to Power and other writings, and has been amplified by the brilliant contemporary Nietzschian E. M. Cioran, whose essay “On Sickness” begins: “Whatever his merits, a man in good health is always disappointing.” In fact, though Nietzsche never mentioned a specific illness, those famous ideas about illness are mainly a reprise of the clichés about TB.

IV

It seems that having TB had already acquired the associations of being romantic by the mid-eighteenth century. Consider the following exchange in Act I, Scene 1 of Oliver Goldsmith’s satire on life in the provinces, She Stoops to Conquer. Mr. Hardcastle is mildly remonstrating with Mrs. Hardcastle about how much she spoils her loutish son by a former marriage, Tony Lumpkin:

Mrs. H.: And am I to blame? The poor boy was always too sickly to do any good. A school would be his death. When he comes to be a little stronger, who knows what a year or two’s Latin may do for him?

Mr. H.: Latin for him! A cat and fiddle. No, no, the alehouse and the stable are the only schools he’ll ever go to.

Mrs. H.: Well, we must not snub the poor boy now, for I believe we shan’t have him long among us. Any body that looks in his face may see he’s consumptive.

Mr. H.: Ay, if growing too fat be one of the symptoms.

Mrs. H.: He coughs sometimes.

Mr. H.: Yes, when his liquor goes the wrong way.

Mrs. H.: I’m actually afraid of his lungs.

Mr. H.: And truly so am I; for he sometimes whoops like a speaking trumpet—(TONY halooing behind the Scenes)—O, there he goes—A very consumptive figure, truly.

This exchange suggests that the fantasy about TB was already a received idea, for Mrs. Hardcastle is nothing but an anthology of clichés of the smart London world to which she aspires, and which was the audience of Goldsmith’s play.12 Goldsmith presumes that the TB myth is already widely disseminated—TB being, as it were, the anti-gout. For snobs and parvenus and social climbers, TB was one index of being genteel, delicate, sensitive. With the new mobility (social and geographical) made possible in the eighteenth century, worth and station are not given; they must be asserted. They were asserted through new notions about clothes (“fashion”) and new attitudes toward illness. Both clothes (the outer garment of the body) and illness (a kind of interior decor of the body) became tropes for new attitudes toward the self.

Shelley wrote on July 27, 1820 to Keats, commiserating as one TB sufferer to another, that he has learned “that you continue to wear a consumptive appearance.” This was no mere turn of phrase. Consumption was understood as a manner of appearing, and that appearance became a staple of nineteenth-century manners. “Chopin was tubercular at a time when good health was not chic,” Camille Saint-Saëns wrote in 1913. “It was fashionable to be pale and drained; Princess Belgiojoso strolled along the boulevards…pale as death in person.” Saint-Saëns was right to connect an artist, Chopin, with the most celebrated femme fatale of the period, who did a great deal to popularize the tubercular look. The TB-influenced idea of the body was a new model for aristocratic looks—at a moment when aristocracy stops being a matter of power, and starts being mainly a matter of image. (“You can never be too rich. You can never be too thin,” the Duchess of Windsor once said.)

Indeed, the romanticizing of TB is the first widespread example of that distinctively modern activity, promoting the self as an image. The look of TB had, inevitably, to be considered attractive once it came to be considered a mark of distinction, of breeding. “I cough continually!” Marie Bashkirtseff wrote in the once widely read Journal which was published, after her death at twenty-four, in 1887. “But for a wonder, far from making me look ugly, this gives me an air of languor that is very becoming.” What was once the fashion for aristocratic femmes fatales and aspiring young artists became, inevitably, the province of fashion as such. Indeed, twentieth-century women’s fashions (with their cult of thinness) are the last stronghold of the metaphors associated with the romanticizing of TB in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Much of the material for the cluster of literary and erotic attitudes known as “romantic agony” derives from tuberculosis and its transformations through metaphor. Agony became romantic in a stylized account of the preliminary symptoms of the disease (for example, debility is transformed into languor) and the actual agony was simply suppressed. Wan, hollow-chested young women and pallid, rachitic young men vied with each other as candidates for this mostly (at that time) incurable, incapacitating, really awful disease. “When I was young,” wrote Théophile Gautier, “I could not have accepted as a lyrical poet anyone weighing more than ninety-nine pounds.” (Note that Gautier says lyrical poet, apparently resigned to the fact that novelists had to be made of coarser and bulkier stuff.) Gradually, the tubercular look, which symbolized an appealing vulnerability, a superior sensitivity, became more and more the province of women—while great men of the mid and late nineteenth century grew fat, founded industrial empires, wrote thousands of novels, made wars, and plundered continents.

We might reasonably suppose that this romanticization of TB was some kind of merely literary transfiguration of the disease, and that in the era of its great depredations TB was probably thought to be disgusting—as cancer is now. Surely everyone in the nineteenth century knew about, for example, the stench in the breath of the consumptive person. Yet all the evidence indicates that the cult of TB was not simply an invention of romantic poets and opera librettists but a widespread attitude, and that the person dying (young) of TB really was perceived as a “romantic” personality. That is, as someone “interesting.” One must suppose that the reality of this terrible disease was no match for the importance of new ideas—particularly about individuality. It is with TB that the idea of individual illness is articulated, and in the images surrounding the disease we can see emerging a modern idea of individuality that has taken in the twentieth century more affirmative, if no less narcissistic, forms.

The romantic treatment of death asserts that people were individualized, made more interesting, by their illness. “I look pale,” said Byron, looking in the mirror. “I should like to die of a consumption.” Why? asked his friend Tom Moore, himself a tubercular, who was visiting Byron in Patras in February 1828. “Because the ladies would all say, ‘Look at that poor Byron, how interesting he looks in dying.’ ” Perhaps the key discovery of the romantic sensibility is not the aesthetics of cruelty and the beauty of the morbid (as Mario Praz suggested in his famous book) or even the demand for unlimited personal liberty, but the nihilistic and sentimental idea of “the interesting.”

Sadness made one “interesting.” It was a mark of refinement, of sensibility, to be sad. That is, to be powerless. In Stendhal’s Armance, the anxious mother is reassured by the doctor that her son is not, after all, suffering from tuberculosis but only from that “dissatisfied and critical melancholy characteristic of the young men of his generation and position.” Sadness and tuberculosis became synonymous. Henri Amiel, the Swiss writer and tubercular, wrote in 1852 in his Journal intime:

Sky draped in gray, pleated by subtle shading, mists trailing on the distant mountains; nature despairing, leaves falling on all sides like the lost illusions of youth under the tears of incurable grief…. The fir tree, alone in its vigor, green, stoical in the midst of this universal tuberculosis.

But it takes a “sensitive” person to feel such sadness—or, by implication, to contract tuberculosis. The myth of TB constitutes the next-to-last episode in the long career of the ancient idea of melancholy—which was also the artist’s disease, according to the theory of the four humours. The melancholy character—or the tubercular—was a superior one: sensitive, creative, a being apart. Keats and Shelley may have suffered atrociously from the disease. But Shelley consoled Keats that “this consumption is a disease particularly fond of people who write such good verses as you have done….” So well established was the cliché which connected TB and creativity that at the end of the century one critic suggested that it was the progressive disappearance of TB which accounted for the current decline of literature and the arts.13

But the myth of TB provided more than an account of creativity. It supplied an important model of bohemian life, lived with or without the vocation of the artist. The TB sufferer was a dropout, a wanderer in endless search of the healthy place. TB became a new reason for exile, for a life that was mainly traveling. There were special places thought to be good for tuberculars: in the early nineteenth century, Italy; then islands in the Mediterranean or the South Pacific; in the twentieth century, the mountains, the desert—all landscapes that had themselves been successively romanticized. Keats was advised by his doctors to move to Rome; Chopin tried the islands of the western Mediterranean; Robert Louis Stevenson chose a Pacific exile; D. H. Lawrence wandered over half the globe. The Romantics invented invalidism as a pretext for leisure, and for dismissing bourgeois obligations in order to live only for one’s art. It was a way of retiring from the world without having to take responsibility for the decision—the story of The Magic Mountain. After passing his exams and before taking up his job in a Hamburg ship-building firm, young Hans Castorp makes a three-week visit to his tubercular cousin in the sanatorium at Davos. Just before Hans “goes down,” the doctor diagnoses a spot on his lungs. He stays for the next seven years.

She Stoops to Conquer was written in 1773, Murgers’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème in 1848, Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, La Traviata in 1853, On the Eve in 1860, and The Wings of the Dove in 1902. How are we to explain that for well over a century it was possible so to romanticize tuberculosis, in spite of the irrefutable medical and human experience? It is true that there was a certain reaction against the early-nineteenth-century cult of the disease in the second half of the century. Nevertheless, TB retained most of its romantic attributes—as the mark of a superior nature, a becoming frailty—through the end of the century and well into ours. It is still the sensitive young artist’s disease in O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night. Kafka’s letters are a compendium of speculations about the meaning of tuberculosis, as is The Magic Mountain, published in 1924, the year Kafka died. Much of the irony of The Magic Mountain turns on Hans Castorp, the stolid burgher, getting TB, the artist’s disease—for Mann’s novel is a late, self-conscious commentary on the myth of TB. But the novel still reflects the myth: the burgher is indeed spiritually refined by his disease. To die of TB was still mysterious and (often) edifying, and remained so until practically nobody in Western Europe and North America died of it anymore. Although the frequency of the disease began to decline precipitously after 1900 because of improved hygiene, the mortality rate among those who contracted it remained high; the myth only came to an abrupt end when proper treatment was finally developed, with the discovery of streptomycin in 1944 and the introduction of isoniazid (INH) in 1952.

If it is still difficult to imagine how the reality of such a dreadful, painful disease could be transformed so pre-posterously, it may help to consider a comparable act of distortion, under the pressure of the need to express romantic attitudes about the self, in our own era. The object of the distortion is not, of course, cancer—a disease which nobody has managed to glamorize (though it fulfills some of the functions as a metaphor that TB did in the nineteenth century). The comparable distortion—taking a loathsome, painful disease and making it the index of a superior sensitivity, the vehicle of “spiritual” feelings and “critical” discontent—in the twentieth century is with insanity.

The fancies associated with tuberculosis and insanity have many parallels. In both diseases, there is confinement. Sufferers are put into a “sanatorium” (the common word for a clinic for tuberculars and the most common euphemism for an insane asylum). Once put away, the patient enters a special world with special rules. Like TB, insanity is a kind of exile. The metaphor of the psychic voyage is an extension of the romantic idea of travel that was associated with tuberculosis. To be cured, the patient has to be taken out of his or her daily world. It is not an accident that the most common metaphor for an extreme psychological experience viewed positively—whether it is produced by drugs or by becoming psychotic—is a trip.

In the twentieth century the cluster of metaphors and attitudes formerly attached to TB split up, and are parceled out to two diseases. Some features of TB go to insanity: the notion of the sufferer as a hectic, reckless creature of passionate extremes, someone too sensitive to bear the horrors of the vulgar, everyday world. Other features of TB go to cancer—the hideous, demonic ones; the ones that can’t be romanticized.

(This is the first part of a two-part article.)

This Issue

January 26, 1978

-

1

Godefroy’s Dictionnaire de l’ancienne langue française cites Bernard de Gordon’s Pratiqum (1495): “Tisis, c’est ung ulcere du polmon qui consume tout le corp.” ↩

-

2

The same etymology is given in the standard French dictionaries. “La tubercule” was introduced in the sixteenth century by Ambroise Paré from the Latin tuberculum, meaning “petite bosse” (little lump), which comes from the Latin tuber, meaning “truffe” or “excroissance.” In Diderot’s Encyclopédie (1765), the entry on tuberculosis cites the definition given by the English physician Richard Morton in his Phtisiologia (1689): “des petits tumeurs qui paraissent sur la surface du corps.” ↩

-

3

As cited in the OED, which gives as an early figurative use of “canker”: “enuie which is the canker of Honour”—Bacon, 1597. And as an early figurative use of “cancer” (which replaced “canker” around 1700): “Sloth is a Cancer eating up that Time Princes should cultivate for Things sublime”—Bishop Thomas Ken, 1711. ↩

-

4

Nearly a century later, in his edition of Katherine Mansfield’s posthumously published Journal, John Middleton Murray uses similar language to describe Mansfield on the last day of her life. “I have never seen, nor shall I ever see, anyone so beautiful as she was on that day; it was as though the exquisite perfection which was always hers had taken possession of her completely. To use her own words, the last grain of ‘sediment,’ the last ‘traces of earthly degradation,’ were departed forever. But she had lost her life to save it.” More of the reality of Mansfield’s suffering is to be found in her own journal entries. ↩

-

5

Georg Groddeck, The Book of the It (Vintage, 1961), p. 104. ↩

-

6

One example, among many, that long predates the Romantic movement is a passage in Act II, Scene 2 of Sir George Etherege’s play The Man of Mode (1676): “When love grows diseas’d, the best thing we can do is to put it to a violent death; I cannot endure the torture of a lingring and consumptive passion.” ↩

-

7

The myth persists. For example, Kenneth Clark, describing Ruskin’s inability to propose to Adele Domecq, says: “His passion brought on a mild attack of tuberculosis” (Ruskin Today, edited by Clark, Penguin Books, 1964, p. 26). So much for the germ theory of disease. ↩

-

8

Esquire, November 1977, p. 128. ↩

-

9

Reich Speaks of Freud (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967), p. 6. ↩

-

10

Groddeck, op. cit, pp. 101-102. The passage continues: “ because desire increases during the illness, because the guilt of the ever-repeated symbolic dissipation of semen in the sputum is continually growing greater, because the It allows pulmonary disease to bring beauty to the eyes and cheek, alluring poisons!” ↩

-

11

Reich, op. cit., p. 6. Cf. p. 20: “He was very unhappily married. I don’t think his life was happy. He lived a very calm, quiet, decent family life, but there is little doubt that he was very much dissatisfied genitally. Both his resignation and his cancer were evidence of that.” ↩

-

12

Goldsmith, who was trained as a doctor and practiced medicine for a while, had his own clichés about TB. In his essay “On Education” (published in 1759 in a magazine called The Bee) Goldsmith writes that a diet lightly salted and seasoned “corrects any consumptive habits, not unfrequently found amongst the children of city parents.” Note that consumption is viewed as a habit, a disposition (if not an affectation), a weakness that must be strengthened, and something to which city people are more disposed. ↩

-

13

Cited in René and Jean Dubos, The White Plague (Little, Brown and Company, 1952), p. 60. ↩