The major retrospective exhibition of Saul Steinberg’s work at the Whitney Museum which opened in April chronicles a unique artistic development. The volume under review here has been “published in conjunction with” the show, but it is by no means merely an illustrated catalogue of the exhibition, or merely the most recent of the artist’s books of published work, or even an occasion for Harold Rosenberg’s wise and pointed essay. It includes and transcends these.

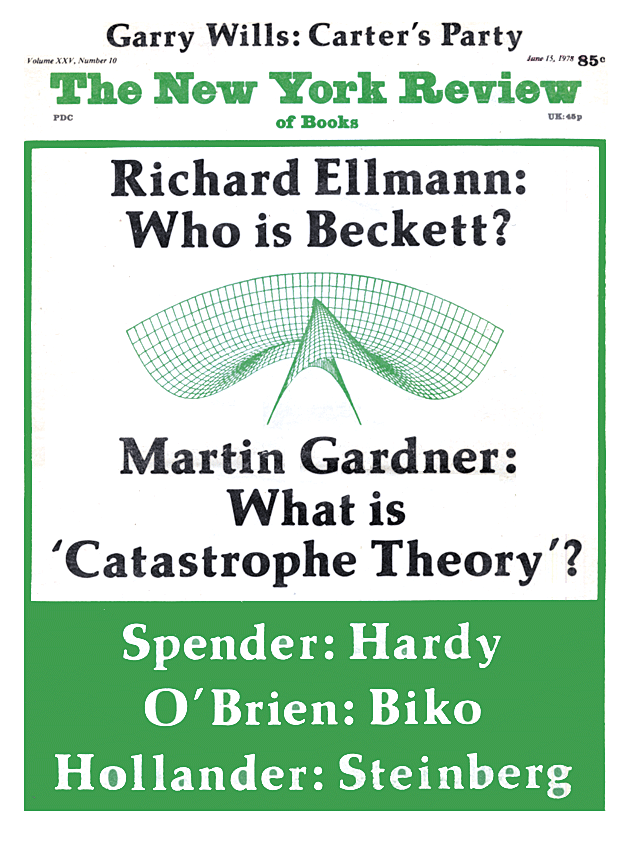

Its front cover reproduces the “Album” containing Steinberg’s famous mock-passport of 1953 and some later additions—drawn group photograph, a much revised ms. with canceled verse and prose in different inks, stamped with a collector’s seal—from 1968. The back cover is the brown paper bag “Hostess Mask.” Depending upon how speculative your temperament, either one can serve to invite you inside.

Steinberg’s uniqueness is as celebrated as the artist himself. A comic and satiric draftsman who evolved into a visionary one, he has no simple prototypes: it is as if he started out in a land not uncongenial to Rowlandson, then moved to both the deeper social and aesthetic concerns of Hogarth. By now, one must invoke Blake as well. In older English, “the pen” and “the pencil” (meaning the paintbrush) were synecdoches for literature and art. For Steinberg, they became each other, and his pictures are a kind of literature in the language of picturing. He has likened his own art to that of the novelist, but his accomplishment is more like that of a philosophical aphorist—G.C. Lichtenberg (teacher of science, interpreter of Hogarth), for instance, whose characterization of a small town as a place where the faces of all the people rhyme is like an early Steinberg drawing. A later drawing might be like another of Lichtenberg’s remarks, to the effect that “a donkey is a horse translated into Dutch,” sitting there, awaiting interpretation. We gradually realize that (a) this is funny only in German or English, because written Dutch seems like those languages but distorted from the viewpoint of either one, and that (b) realizing (a) makes the remark even funnier; by commenting on its own axioms, it calls our own visual and verbal parochialism into question. (Why isn’t a horse a distorted donkey, for example?)

Steinberg’s drawings have always dealt with the language of inscription and, indeed, even the history of art itself becomes reinterpreted as part of the vast sketchbook that human culture scrawls everywhere, and that even nature—“creeping up” on art (as Whistler once put it)—continues to do as well. His art has always embraced written language, as well as substituting for it; but he also literally writes with extraordinary power, using some of the same tropes and fables that he does in drawing:

The view from the car is false, menacing; one is seated too low, as if in a living-room chair watching TV in the middle of a highway. From the bus, one has a much better and nobler view, the view of the horseman. It is a pity that now they color the bus windows and one sees only a sad, permanent twilight.

This is a comment from the present volume on his bus trips around America, and among other things it helps to clarify the nature of the nobility of the tiny lancer-on-horseback, an emblem appearing in some of his pictures of the last fifteen years.

It is not the least of the virtues of this book that it allows us to hear the artist as well as to see his work. It is also truly a retrospective volume, in its profusion of color plates, as well as black and white, and its biographical apparatus. Not only does it represent various phases of a career, with the selection weighted—quite properly, I believe—toward the allegorical and visionary pictures, whereas the exhibition tends to favor sequences and large-scale pictures. It also enables us to see what had, in a sense, been going on behind an entrancing masquerade for thirty years. Perhaps this can be understood by considering Steinberg’s previous books.

Steinberg’s first book of drawings was All in Line (1945), published while the artist was still masquerading—as he would put it—as a cartoonist. It contained New Yorker drawings of reportage from various “theaters” of World War II—drawings that gave back to that technical military term some of its old meaning—as well as cartoons. In addition, it presented, in the guise of cartoons, some of the germs of the art of the great graphic aphorist that was to come. An aphorism, according to the ground rules laid down by W.H. Auden, has to be true and may or may not be funny; whereas an epigram has to be funny, and may or may not be true. Steinberg’s first drawings of people drawing themselves—the man with the bottle of ink, the wonderful curving chain of representations, in which a hand draws one man who is drawing another who is drawing another who is drawing another, and so forth—were passing magazine muster on their wit, rather than on their truth.

Advertisement

So, doubtless, was his schematic clock, its hands moving in successive drawings from 12:05 to 12:45, consuming itself in narrowing wedges like the emblematic pie of economic diagrams, and so, too, were his first cartoon couples—the large mothers greeting each other while, a good deal below, their reciprocal small daughters glare distrustfully; the couple removing their respective eyeglasses, drawn in the same linear mode as their wearers—who, in Steinberg’s later art, would become the splendid mismatched couples, married pairs rendered in incompatible or otherwise complicatedly related drawing styles, in the pages of The Passport (1954). The cartoons would eventually reveal themselves to be drawings and the visual epigrams would unmask their true, deep aphorisms.

That the cartoonist and journalist were an artist of another sort, disguised, can be discerned in hindsight from the titles of his books. “All in Line” described the linear style of the drawings; when the book appeared, one could hardly know how much more it meant for the artist himself. These were the inscriptions of an immigrant who knew so much of waiting in line, at borders and points of entry (their very names suggest allegories in graphic terms). As drawings, they were themselves in line for inspection and understanding. The Art of Living (1949) included Steinberg’s first collages, metamorphic series, changes rung on visual puns—the ruled orchestral score paper whose lines are variously seen as the bands of a muscle developer, falling rain, etc.—and even the first documents, studies in the rhetoric of calligraphic gesture. Here again, the title means many things, but one of these is surely a masquerade of “the life of art.” To have grouped Steinberg at this point in his career with émigré artists in New York, like Gorky and de Kooning, who would emerge as major painters, would have then seemed frivolous or irresponsible: only his close friends could probably have known how personal were the very metaphors with which his pictorial concepts played.

But during the subsequent decade another emigration was slowly going on. Steinberg had earlier moved from Bucharest to Milan, where he studied architecture and began to do cartoons for the satiric magazine Bertoldo. Thence, by stages, he came to the United States in 1942, where he traveled some, joined the Navy, and traveled again. His languages had been Rumanian (with Yiddish in the background), Italian, and then English. Now the emigration was in his “life of art.” With the credentials of The Passport he entered another domain. This remarkable volume explored the world of documents—identification papers, certificates, ex votos, and the like—both those which contained pictures and those whose emblematic significance lay totally in what their graphic styles implied. Like the scribal rhetoric of Steinberg’s renderings of architectural façades—scrawled, doodled, ruled, smudged, each style becoming one with a mode of rendering it in black and white—the documents and monuments of The Passport were more than merely a scene of ridicule, exposing the floridity of the forms by which the state proclaims and maintains its place in the lives of individuals. They revealed scenes of irony, joy, nostalgia, and vision as well.

Written language, like the vocabulary and grammar of decorative cliché, ceased to be a system of signs and revealed itself as a world of graphic wonder. (An equivalent for any of us might be a state of visionary mind in which all red traffic lights, say, became important for their color—is this a splash of tomato hanging above me? Is that car ahead thinking of watermelons?—instead of for their assigned meaning: STOP! This is some of what Blake meant by seeing through the eye not with it.)

The world of art to which The Passport led was a territory in which styles of architectural, domestic, sumptuary, personal—and, standing for all of these, graphic—design were as much a part of urban nature as the things and persons thereby styled. The passport photo made of smears of fingerprint, written, printed, and rubber-stamped over with the official language of an unreadable and therefore purely visionary authority—this was the book’s title object. But the title was also, as I have suggested, important in its immediate figurative sense for Steinberg personally: the drawings themselves were a passport into high art as well as the first papers for citizenship there, in a republic whose language he would always be as much privileged as condemned to speak with an accent.

Advertisement

In The Labyrinth (1960) and The New World (1965) Steinberg continued to explore the inner and outer experience of Art and America, expanding and deepening it, and incorporating a wider variety of work done for exhibition rather than primarily for reproduction. Publishing a book became a more complex matter than merely assembling a sample or phase of work. Photographic collages and paste-ups; masks drawn on paper bags and then photographed on their wearers; intricate allegorical landscapes and schematic structures; profound pictorial interactions between drawn lines and concrete—but illegible and nonsignifying—rubber stamps of his own devising (he had played with these in childhood); the simulation of old and inept snapshot photography in pencil and wash; calligraphic representations of speech and musical sounds; landscapes and heroic narratives involving solid letters and words, their physical relations, their cast shadows, their presences and distances—all of these emerged during the 1960s and after. The books of published drawings continued to confine themselves to black and white. The Inspector (1973) was the most recent of this series, and its title reminds us that the frequently inspected immigrant had himself become the inspector. (How amused the Italian-speaking cartoonist and comic draftsman must have been to discover that le doganiere—le douanier, der Zollaufseher—was called in the US an inspector of customs.)

But Steinberg had become more than that, just as his rubber-stamped seals, animals, and people had transcended an earlier satiric role as emblems of national sates asserting their authority over physical domains and states of feeling and knowing. Steinberg started doing little oils and wash drawings in the 1960s. (His solid, architecturally monolithic capital letter E, in the mid-ground of a sad twilit landscape, dreaming by means of a comic-strip cloud balloon of a slim, elegantly serifed, grave-accented version of itself, was one of the earliest of these.) To give scale to these little shore-scapes—they were at first of intimate beaches like Louse Point in Springs, NY—he would stamp in a human viewer. This could be considered as a means of avoiding the problems of figure painting, just as it gave not only scale but meaning—as Blake said, “where man is not, nature is barren”—to the picturing of the scene, and hence to the scene itself. It also helped to expand the significance of the stamp. Round, official seals appeared in the skies of these little paintings, both as Steinbergian suns and as versions of the flamboyant cartouches that hang in the skies above German Renaissance paintings (Altdorfer, Grünewald). Finally, they constituted stamps of approval, certifications of one part of the artist’s oeuvre by the authority of the other.

Steinberg has exhibited drawings, and more recently paintings and constructions, since 1945. In 1946 he appeared in a Museum of Modern Art exhibition of “Fourteen Americans” (among the memorable others were Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Mark Tobey, David Hare, and Isamu Noguchi). He has had over sixty one-man shows since then, and has appeared in many group exhibitions as well. But hanging on walls of galleries has always been a different matter from appearing on flat pages that throw back, mirror-like to the reader of pictures, a version of the confrontation with the tabula rasa which he, too, once was. During the two decades when Steinberg’s art was becoming more and more overtly personal, embodying allegorical pictures of journeys, maps, transitions from one inner state to another, it was also lurking on the border between the world of gallery art and the domain of the book. Many exhibition catalogues—like issues of Galerie Maeght’s Derrière le Miroir—were reproducing his work in color, sometimes very elaborately, and with commentaries by writers such as Michel Butor and Italo Calvino. More and more of his work was conceived for exhibition. His use of scale, color, media all transcended the possibilities of the page. In the 1970s Steinberg began to assemble his wooden work tables with carved, painted note and sketch books, pencils, pens, etc., whose sculptural sketchiness parodied graphic approaches to three dimensions.

At the same time, he was beginning to paint (many people learn to paint when young, he half-explained at the time, and only a few become artists; he was an artist, and so could learn now to paint). The history of art had always been part of the subject matter of his inspections. Both the world of American art and the New York art world (with their uneasy relations) came under his scrutiny. He observed the rise and flowering of American abstract painting and stood always to one side of it; his comment that abstract-expressionist artists were painting their signatures was by no means a reductive satiric observation—for years he had been re-writing his. But in not painting he was in a sense not taking on some of the major problems confronting American artists: the significant reinvention of pictorial space and, perhaps even more important, the organic scale of elements within a painting. It was not that he was evading such problems. Rather, the visual record of their solutions by contemporary painters was what hung in galleries and museums, to be inspected by people who themselves could look like solutions to aesthetic problems (see his pictures of people looking at paintings, or of architects and their buildings). Paintings to his eye and pen look like part of the natural world of gesture, style, and unwitting visual metaphor that he has always drawn, seldom without making some comment of his own on the portentousness and fragility of the solutions themselves. His own landscape paintings grew more and more metaphorical. Brought under the conceptual control of the rubber stamps, picture postcard format, official writing, and other devices, they became part of the record of his visionary diaspora. The very large (48″ X 78″) shore landscape called The Tree in the Whitney exhibition—the book page gives one no sense of its size—makes by its very scale a kind of declaration of independence from its elements of Steinbergian authentication—tiny people, two stamped seals—which are dwarfed by the painterly expanse. (Its consequences for the future of his oeuvre are yet to be seen.)

The current retrospective show catches Steinberg at a fascinating point in his career: he has himself characterized the exhibition as one more immigration, both, one would suppose, into a position of retrospect and into whatever the Whitney Museum can (regardless of how often, these days, it does not) stand for. The book entitled Saul Steinberg is a documentation of his career on the page and on the wall. It is itself retrospective of his past exhibition catalogues, and it is a Steinbergian masquerade of a book about an artist. Aside from Harold Rosenberg’s knowing, broad-ranging, and appropriately discursive introduction, illustrated and, from time to time, footnoted by the artist himself, there is an illustrated chronology, with bare biographical facts in roman type and Steinberg’s own comments in italics. Here are his own actual first passport, some early drawings, etc., along with other photographs and drawings used for documentation—the apparatus includes a selected bibliography—and yet, one feels, on the edge of withdrawal into some kind of parody.

Perhaps this is because Saul Steinberg is more than just an exhibition catalogue with adjustments; it is an epitome and summary of Steinberg’s published volumes as well. Its title has the kind of irony that those of his previous books do; in this case, the name of a man, of an exhibition, of an oeuvre, all come together. (I think of how, as one critic has reminded us, the popular error of misnaming Frankenstein’s monster as its creator affirms the truth that we invoke in referring to a body of work as Shakespeare or Rembrandt.) The book is not so much a mixed metaphor as a reunion of two wanderers. The necessary alterations of scale which any art book enforces on its reproductions entail the usual losses that such enshrinement occasions. On the other hand, many of the documentary works of the past—hither to reproduced only in black and white—are now seen in the poignant tints of official paper. There are quite a few examples from the very large selection of carved objects—work tables and the like—in the show. But seeing these pictured makes one notice certain things anew, such as the flat, scribbled-over pieces of wood, shaped like small cricket-bats but with pointed handles, which are abstractions of comic-strip balloons, the containers of one incisive kind of graphic language. Steinberg’s way of playing with these shapes, widening and flattening them with parallel top and bottom, makes them look like the cartouches surrounding the royal names on the Rosetta Stone that helped Champollion to decipher the hieroglyphic script.

Neither this book nor the show it accompanies is going to make the question about what kind of artist Steinberg is any easier to answer; both make the question more important, and certainly deeper. One phase of this masquerade is in any event over. What lies between the covers of Saul Steinberg has been opened to another kind of inspection, one familiar to readers of texts, if occasionally perplexing to walkers of galleries. As Steinberg himself remarked to Pierre Schneider as they walked through the Louvre in 1967, “Art is a sphinx. The beauty of the sphinx is that you yourself must do the interpreting….Interpretation probably does not give us the truth, but the act of interpreting saves us.”

This Issue

June 15, 1978