I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland

by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on

in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice

that ripples between them like hair still moist,

if it ripples at all. Propped on a pallid elbow,

the helix picks out of them no sea rumble

but a clap of canvas, of shutters, of hands, a kettle

on the burner, boiling—lastly, the seagull’s metal

cry. What keeps hearts from falseness in this flat region

is that there is nowhere to hide and plenty of room for vision.

Only sound needs echo and dreads its lack.

A glance is accustomed to no glance back.

The North buckles metal, glass it won’t harm;

teaches the throat to say “Let me in.”

I was raised by the cold that, to warm my palm,

gathered my fingers around a pen.

Freezing, I see the red sun that sets

behind oceans, and there is no soul

in sight. Either my heel slips on ice, or the globe itself

arches sharply under my sole.

And in my throat, where a boring tale

or tea, or laughter should be the norm,

snow grows all the louder and “farewell”

darkens like Scott wrapped in a polar storm.

A list of some observations. In a corner, it’s warm.

A glance leaves an imprint on anything it’s dwelt on.

Water is glass’s most public form.

Man is more frightening than his skeleton.

A nowhere winter evening with wine. A black

porch resists an osier’s stiff assaults.

Fixed on an elbow, the body bulks

like a glacier’s debris, a moraine of sorts.

A millennium hence, they’ll no doubt expose

a fossil bivalve propped behind this gauze

cloth, with the print of lips under the print of fringe,

mumbling “good night” to a window hinge.

You’ve forgotten that village lost in the rows and rows

of swamp in a pine-wooded territory where no scarecrows

ever stand in orchards: the crops aren’t worth it,

and the roads are also just ditches and brushwood surface.

Old Nastasya is dead, I take it, and Pesterev, too, for sure,

and if not, he’s sitting drunk in the cellar

or is making something out of the headboard of our bed:

a wicket-gate, say, or some kind of shed.

And in winter, they’re chopping wood and turnips is all they live on,

and a star blinks from all the smoke in the frosty heaven,

and no bride in chintz at the window, but dust’s gray craft,

plus the emptiness where once we loved.

Near the ocean, by candle light. Scattered farms,

fields overrun with sorrel, lucerne, and clover.

Towards nightfall, the body, like Shiva, grows extra arms

reaching out yearningly to a lover.

A mouse rustles through grass. An owl drops down.

Suddenly-creaking rafters expand a second.

One sleeps more soundly in a wooden town,

since you dream these days only of things that happened.

There’s a smell of fresh fish. An armchair’s profile

is glued to the wall. The gauze is too limp to bulk at

the lightest breeze. And a ray of the moon, meanwhile,

draws up the tide like a slipping blanket.

There is always a possibility left—to let

yourself out to the street whose brown length

will soothe the eye with doorways, the slender forking

of willows, the patchwork puddles, with simply walking.

The hair on my gourd is stirred by a breeze

and the street, in distance, tapering to a V, is

like a face to a chin; and a barking puppy

flies out of a gateway like crumpled paper.

A street. Some houses, let’s say,

are better than others. To take one item,

some have richer windows. What’s more, if you go insane,

it won’t happen, at least, inside them.

…and when “the future” is uttered, swarms of mice

rush out of the Russian language and gnaw a piece

of ripened memory which is twice

as hole-ridden as real cheese.

After all these years it hardly matters who

or what stands in the corner, hidden by heavy drapes,

and your mind resounds not with a seraphic “doh,”

only their rustle. Life, that no one dares

to appraise, like that gift-horse’s mouth,

bares its teeth in a grin at each

encounter. What gets left of a man amounts

to a part. To his spoken part. To a part of speech.

Not that I am losing my grip: I am just tired of summer.

You reach for a shirt in a drawer and the day is wasted.

If only winter were here for snow to smother

all these streets, these humans; but first, the blasted

green. I would sleep in my clothes or just pluck a borrowed

book, while what’s left of the year’s slack rhythm,

like a dog abandoning its blind owner,

crosses the road at the usual zebra. Freedom

is when you forget the spelling of the tyrant’s name

and your mouth’s saliva is sweeter than Persian pie,

and though your brain is wrung tight as the horn of a ram

nothing drops from your pale-blue eye.

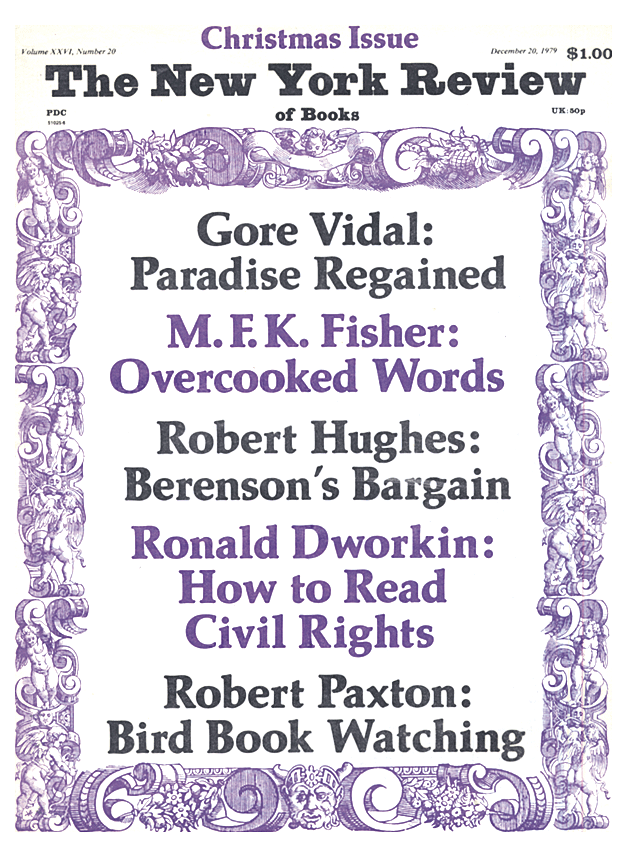

This Issue

December 20, 1979