from The Sinking of the Titanic

I remember Havana, the plaster coming down

from the walls, a foul insistent smell

choking the harbor, the past voluptuously fading,

and scarcity gnawing away, day and night,

at the Ten Year Plan, full of longing,

while I worked at The Sinking of the Titanic.

There were no shoes, no toys, no light bulbs,

and there was not a moment of calm, ever,

and the rumors over the crowd

were thick as flies. I remember us thinking:

Tomorrow things will be better, and if not

tomorrow, then the day after. O.K.—

perhaps not much better really,

but different, anyway. Yes, everything

was going to be quite different.

A marvelous feeling. Oh, I remember it.

I write these words in Berlin, and like Berlin

I smell of old cartridge cases,

of the East, of sulfur, of disinfectant.

It is getting colder again, little by little,

and little by little I’m reading the regulations.

In the distance there is the Wall, unnoticed,

hidden by many movie houses, and behind it

a few desolate movie houses disappear in the distance.

I see lonely foreigners in brand-new shoes

deserting across the snow in solitude.

I am cold. I remember—it’s hard to believe,

not even ten years have passed since—

the rare light days of euphoria.

Nobody ever gave a thought to Doom then,

not even in Berlin, which had outlived

its own end long ago. The island of Cuba

did not reel beneath our feet. It seemed to us

as if something were close at hand,

something for us to invent. We did not know

that the party had finished long ago,

and that all that was left was a matter

to be dealt with by the man from the World Bank

and the comrade from State Security,

exactly like back home and in any other place.

We had tried to get lost and to find something

on this tropical island, where the grass grew

over ancient Cadillac wrecks. The rum had gone,

the bananas had vanished, but we

were looking for something else—

hard to say what it really was—

but we could not find it

in this tiny New World

eagerly discussing sugar,

liberation; and a future abounding

in light bulbs, milk cows, brand-new machines.

Mulatto girls at the street corners

cradling their automatic rifles

smiled at me in Havana, at me

or at someone else, while I worked

and worked on The Sinking of the Titanic.

I couldn’t sleep, the nights were hot;

I lived by the sea; I wasn’t middle-aged,

I was not a kid, but I was younger

than now by ten years, and pale with zeal.

It must have happened in June, no,

it was in April, shortly before Easter,

we took a walk down the Rampa,

it was past midnight, Maria Alexandrovna

looked at me, her eyes shining with rage,

Heberto Padilla smoked a cigar,

he had not yet gone to prison, but who

remembers him now, a lost man,

a lost friend, Padilla, and a deserter

from Germany shaking with shapeless laughter,

he too went to prison, but that was later,

and now he is here again, back home, boozing

and doing research in the interest of the nation,

and it is odd that I still remember him.

There is not much that I have forgotten.

We talked and jabbered away in a medley

of Spanish, German and Russian

about the terrible sugar harvest

of the Ten Million Tons—nowadays

nobody mentions it any more, of course.

Damn the sugar! I came here as a tourist!

the deserter howled, and then he quoted

Horkheimer—Horkheimer of all people,

in Havana! We spoke of Stalin, too,

and of Dante, I cannot imagine why,

cutting cane was not Dante’s line.

And I looked out with an absent mind

over the quay at the Caribbean Sea,

and there I saw it, very much greater

and whiter than all things white, far away,

and I was the only one to see it out there

in the dark bay, the night was cloudless

and the sea black and smooth like mirror plate,

I saw the iceberg, looming high

and cold, like a cold fata morgana,

it drifted slowly, irrevocably,

white, nearer to me.

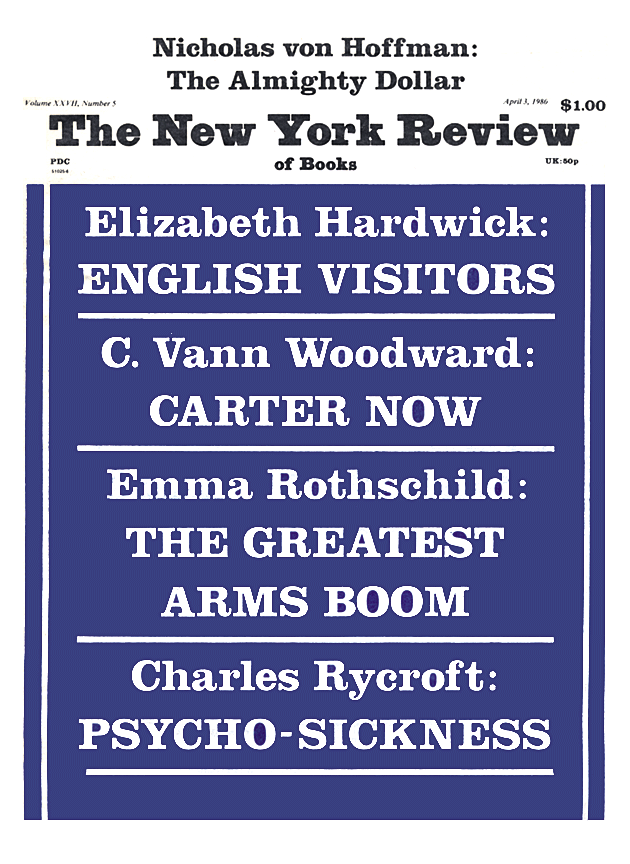

This Issue

April 3, 1980