It is rare indeed that there appears a “picture-book” which in every way, material, editing, production, achieves an excellence worthy of its subject. This monumental gathering of photographs of the most familiar American face amounts to a collective portrait which no contemporary artist caught with lasting satisfaction, and whose two finest sculptures were posthumous.* As James Mellon, collector, editor, and patron of this volume, writes: “In punishing him for having been apotheosized, they [the historians] have refused him the right to be a man.” Ever since martyrdom Lincoln has simultaneously grown nearer and more remote. His credited biographers, Nicolay and Hay, Ida Tarbell, Charnwood, Beveridge, Randall, have enlarged on fact and background, while diminishing his humanity.

Cards representing books about Lincoln in the Library of Congress run to some five thousand. T.S. Eliot, in a preface to his mother’s blank-verse drama laid in the Italian Renaissance, remarked that those who use historical sources tell more about the times in which they write than about the epoch they purport to depict. Carl Sandburg’s six hefty volumes, for decades a criterion, are now put down for poeticizing and prolixity. In his superb Patriotic Gore, Edmund Wilson is severe. While admitting that later editions improved by abbreviation, he wrote of Sandburg’s lifework as “a long sprawling book that eventually had Lincoln sprawling.” Yet “sprawling” suggests a rough-hewn intimacy which more academic biographers dare not or cannot risk. To a degree, The Prairie Years and The War Years parallel portraits of Lincoln (Mellon, plates 49 and 54) from which the face on our five-dollar bill and one-cent copper penny derive.

In Mellon’s breathless gallery few subsidiary persons are seen, save Lincoln’s son Tad, two secretaries, and soldiers at field headquarters. With the reduction of Sandburg (1954) as guide, this collection obliquely but plainly illuminates stages in a metamorphosis. The earliest likeness was probably made in Springfield, Illinois, 1846, when he was thirty-seven years old, and newly elected to the House of Representatives. There is already visible the enigma of his inward focus which will become a signature of so many subsequent portraits. This apartness or self-absorption, the fixity which is more self-centered than pleasing to curious voters, saturates his objectivity. In a campaign autobiography for 1860, when his name was as little known as his face, he wrote:

If any personal description of me is thought desirable, it may be said, I am, in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean, in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and grey eyes—no other marks or brands recollected.

During the 1858 debates with Douglas, a New York Evening Post reporter wrote:

In repose, I must confess, “Long Abe’s” appearance is not comely. But stir him up and the fire of genius plays on every feature.

Photographs had a primary political purpose, to acquaint the electorate ignorant, except in Illinois, of a man whose emergence was, and would remain, miracle and mystery. At the moment of his Cooper Union speech, he visited Matthew Brady’s studio and there posed for the carte-de-visite standing portrait which has been described as the key that clinched his candidature. Widely circulated, the portrait’s first printing was soon exhausted. In response to a request, he wrote from Springfield, April 7, 1860:

While I was there [New York City] I was taken to one of those places where they get such things, and I suppose they got my shadow, and can multiply copies indefinitely.

Lincoln’s photographs fall into three categories, beardless, bearded, in the open air. Least familiar are those cleanshaven. Contrast between these and those whiskered not only present a dual personality but almost two persons. The well-known story that, on his way to the White House, an eleven-year-old girl from upstate New York suggested his appearance might be improved because “all the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you,” is modified by a letter of three days before, October 12, 1860, signed “True Republicans”:

Allow a number of very earnest Republicans to intimate to you, that after oft-repeated views of daguerreotypes; which we wear as our token of devotedness to you; we have come to the candid determination that these medals would be much improved in appearance, provided you would cultivate whiskers and wear standing collars.

Carl Sandburg wrote his publisher Alfred Harcourt, August, 1924, on the completion of The Prairie Years:

…as the book now stands, he [Lincoln] is crossing the state line of Illinois into Indiana, leaving the prairies, starting to grow whiskers. It is the end of the smooth-faced Lincoln, of the man whose time and ways of life belonged somewhat to himself; he is no longer a private citizen who comes and goes, but a public man who must stay put…. It wouldn’t quite do to call it [his initial volume] “The Smooth-Faced Lincoln” or “The Pre-Whiskers Lincoln,” but it delivers the Lincoln who knew the time for whiskers, who has the Chicago Daily News readers buffaloed so that it is a remark in the art-department, “Oh hell, the people don’t want to see Lincoln without whiskers.” So we won’t call the book, “The Well Razored Abe.”

Whatever the well-meant proposals, Lincoln’s decision to grow a beard was his own. It was photographed in full sprout by November 1860. The transformation offers a chance to consider his development as a rising star-actor from what amounted to rehearsal in private—or at least provincial theatricals—to performance on national and international scenes. The beard, in part, served to conceal or diminish a treacherous nudity of expression betraying the disturbing oddity of an X-ray intelligence. The editor of a Wisconsin newspaper wrote in September, 1859:

Advertisement

He looks as if he was made for wading in deep water. He looks like an open-hearted, honest man who has grown sharp in fighting knaves. His face is swarthy with very deep long thought-wrinkles.

This, without beard. Secretary Stanton called him “The Original Gorilla,” and Confederate cartoonists lampooned him as a monstrous monkey. Searching his face, one finds no hint of discreet narcissism or coquetry. His “ugliness” or asymmetry could be read as a rallying ensign of mid-America, then interpreted as West, new frontiers with endless energy and unsophisticated franchise. His head, topping his height and stance, radiated dark magnetic force. Rail-splitter turned townee, a lanky pioneer assumed the black alpaca of the circuit-rider and he appropriated the standard uniform of a professional politician. Had he posed for Avedon, Cecil Beaton, or Karsh of Ottawa, his mask would have cracked their cameras. Cosmetic hype was beyond the lens of Brady or Gardner. John Hay, Lincoln’s secretary, watched him staring at an ostentatious fraud; he looked through the man “to the buttons on the back of his coat.” As Mellon shrewdly deduced, there are no grins, but while Grant and Sherman fulfill their terrible promises, there is the rising flicker of a smile. Forty seconds or more then required for the photographic process forced rigidity; there are a few blurred hands and faces. A metal head-brace ensured the static pose. What is remarkable in dozens of these pictures is the apparent relaxation in posture which extends to a double portrait with his son Tad.

Those taken out of doors are less instructive in psychological hints. However, they demonstrate Lincoln’s extraordinary stature looming over the usual range of mortals, and powerfully evoke the climate of occasions. In the famous photograph of the President confronting George B. McClellan in his tent, 1862 (Mellon: 34), here splendidly restored and enlarged, we feel the earnest anxiety of a miserable visit. Lincoln had been assailed from every side for his patience with a commander who, heavily superior in men and materials, was pathologically slow to strike. Eventually dismissed, he would oppose Lincoln in 1864 on a stop-the-war platform. A panoramic view of the dedication of the Gettysburg cemetery barely reveals the speakers, yet it is memorable for the sharp looks of a man and his small boy in Union uniform. The father’s attention is toward the speeches; his son’s on the photographer.

Two astonishing pictures show the panoply of the second inauguration, a huge concourse of personages, some blurred, many recognizable. Just above Lincoln can be discerned Frank Carpenter, who spent six months in the White House painting the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Nearby is the dandified figure of John Wilkes Booth with the manager of Ford’s Theater where, six weeks later, Lincoln would be shot. Below, leaning against the wooden barrier, some imagine they have spotted Lewis Paine and George Atzerodt, two of the conspirators who would not escape hanging. In the background is the unfinished façade of the National Capitol, the bronze doors and iron dome of which Lincoln refused to countermand since their completion spelled confidence and continuance.

During his lifetime, a number of painters and sculptors aspired to portray him. In Springfield, 1860, he suffered Leonard Volk to take plaster-casts of his face and hands which were put in bronze. When Volk pried off the dried plaster, not a few hairs came off in the operation, and the President-elect said, with a twinge: “It’s the animal himself.” The life-mask by Volk, clean-shaven, and a later one less painfully taken by Clark Mills are touching relics, but their forms seem to have shrunk, and devices needed to protect eyeballs transform them to death-masks. No work “taken from life” except a photograph has much claim to distinction, but these heartily inspired a number of artists in the lesser craft of book-illustration. Well into this century these admirable draftsmen reconstructed the Civil War with archaeological insistence. Men like Frank E. Schoonover and N.C. Wyeth provided lively models useful to theater, films, and the popular imagination.

Advertisement

As for bronze or stone images from which emanate active vibrations, two outstanding figures are, hardly by chance, from the hands of the best native sculptors of their time. Although today all but ignored in a small green park opposite the Houses of Parliament, Lincoln shares pride of place with a half-American, Winston Churchill. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s magnificent standing bronze (1884-1889) places the President before a classic civic seat. It is also to be seen in Chicago, for which it was first commissioned, but is now ill-kept. As a boy, Saint-Gaudens saw Lincoln on his way to Washington just before war broke. He took much from the beardless photographs, and while his man is considerably larger than life, placed on a pedestal so high that visual deformation occurs, the statue’s intense drama resides in a heroic intimacy. It is imbued with the immediacy and dispassionate grandeur with which Roman and Renaissance sculptors idealized their heroes. Something of shame it is, that Lincoln Center, soi-disant cultural capital, never slow to borrow his name, holds no mark to his memory.

After Saint-Gaudens’s death, the choice of sculptor for the focal figure in the nation’s memorial inevitably went to his friend and protégé, Daniel Chester French, by no means a negligible talent. Henry Bacon, architect of the Memorial, conceived a Doric temple of more than Attic proportions, but opening on the long side and set on a vast podium of steps. Mounting these to behold the idol within sometimes has the disturbing effect of approaching a pop-up. However, the intention was to elevate the shrine as pendentive to the Capitol four miles away. The Parthenon is on a fortress of rock with little visual contact to the town below. Bacon’s building uses a reflecting pool and a broad mall as a symbolic carpet for a continent. Beardless, enthroned, Lincoln dozes in mineral limbo, flanked on either side by Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural.

A scion of Olympian Zeus, he is nineteen feet high, composed of twenty-eight blocks of flawless marble which took an Italian stonecutter family four years to carve. Head and face derive from the photographs; the scale and stone enforce a generalization, amounting to deification. Gazing at it, would the martyr ghost returned from the grave ask: “Is this the face I shaved?” As with the Statue of Liberty or Washington Monument, both works of art, familiarity breeds less contempt than astigmatism. But the Lincoln Memorial corresponds to a notion of what the nation needs more than it canonizes the person of preserver and emancipator. Where else in the modern world is to be found an earnest popular hommage on so decent and dignified a scale?

As we search the photographs, beardless to full-whiskered, we watch a man not forty, who might be ten years younger, develop into an ageless ancient, which indeed was what two young secretaries nicknamed him. He could be considered no worldly success until relatively late in his career, but he is unlike many failures in that adversity reads less as mischance than apprenticeship. The superiority of Abraham Lincoln over all other statesmen lies in the limitless dimensions of a conscious self, its capacities and conditions of deployment. This sprang from a nature endowed with prescience, conscience, and power which, as Edmund Wilson wrote, place him as supreme statesman, parallel in gift and genius to the greatest artists and scientists. In March 1863, Walt Whitman watched him during some of the worst weeks of the war:

I think well of the President. He has a face like a Hooiser Michael Angelo, so awful ugly it becomes beautiful, with its strange mouth, its deep-cut, criss-cross lines, and its doughnut complexion.

Lincoln’s self-awareness sprang from biomorphic factors also reflected in his physical stature and the unmeasurable love and hate he magnetized. His aura, from the start, was prophetic, his preoccupations metaphysical. Suffering endured stoked his energy with penetration and foresight often hidden from contemporaries. He is now available to us, as never before, through the research of historians and these restored pictures. We come to realize how he put suffering to use; as pressure grew, moral muscle turned Herculean. Life on the frontier, surly litigation, local politics where elementary manners were the custom of the community, comprised civil war in miniature, a post-graduate course in polity which no Yale or Harvard ever offered. At first hand, before he was thirty, he was intimate with every condition in small which later he would face as monstrous.

His emotional life remains profoundly mysterious. He married a luxury-loving woman who was hysterically jealous; she became demented. Two of her half-brothers were Confederate officers. It was widely believed she was a Rebel spy. Two of her sons died, one in the White House. Her closest companion was a mulatto trance-medium. Lincoln himself continued to have nightmares and half-waking visions of the most dreadful anticipatory truth. Not the least of his anguish was a constant dilemma of the execution of deserters. Records of his pardons are famous. It is forgotten that 267 soldiers were shot because he would not further demoralize military justice. His law partner, William H. Herndon, in many ways his closest and most detached witness, wrote a biography which gave offense. Robert Lincoln, the son, considered it sacrilegious, and for years it was an under-the-table item. In an address by Herndon given after the President’s death there is distillation of insight:

Mr. Lincoln’s perceptions were slow, cold, precise, and exact…. Everything came to him in its precise shape—gravity and color. To some men the world of matter and of man comes ornamented with beauty, life, and action, and hence more or less false and inexact. No lurking illusion—delusion—error, false in itself, and clad for the moment in robes of splendor, woven by the imagination, ever passed unchallenged or undetected over the threshold of his mind…. He saw all things through a perfect mental lens. There was no diffraction or refraction there…. He was not impulsive, fanciful, or imaginative, but cold, calm, precise….

The harvest of the lens that Mr. Mellon has gathered is enriched by quotations which face each picture. Brief, adroitly chosen, they are keys to a stupendous chronicle. This book drives us who may feel we, also, pass through parlous times to further humbling study of how such a man of state coped with the fission of a nation, how he fused its torn nucleus through apocalyptic carnage which was the spring for all subsequent industrialized warfare. Take this album as a gloss on Wilson’s Patriotic Gore, Walt Whitman’s threnody and his Specimen Days and Collect.

Technical production is past praise. From the original metal and glass wetplates, Richard Benson, a distinguished artist-photographer, professor of photography at Yale, made film-positives. From these, in an intermediate step, there was a set of negatives from which the final prints were reproduced. The texture and quality of modern woodpulp paper no longer supports the extreme contrast of values present in the original negatives. Benson took as many as three separate negatives of each image to be finally superimposed. This was all done photographically, with no hand-retouching, except for removal of accidental spots and scratches. Each plate had three negatives locked by register-pins so that the ultimate print recovered the original image to its full tonality. Benson, himself a master photo-engraver, supervised the exquisite presswork of the Meriden Gravure Company. Each page went through the press three times, using a black, then gray ink, and a final thin varnish. The process was offset lithography in a 300-line screen, so that the dots are invisible to the naked eye. Enlargements developed have far more definition and legibility than may be seen in the extant copies from contemporary sources.

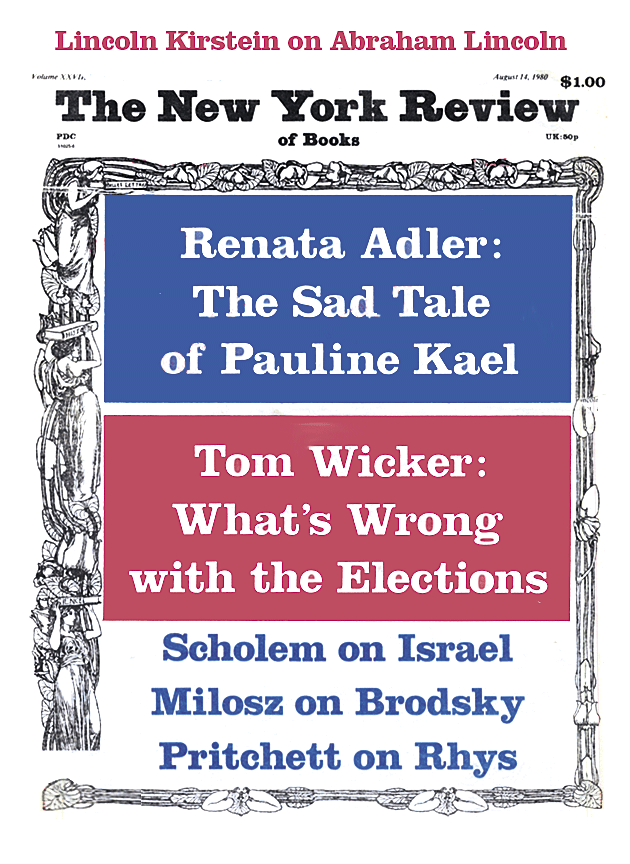

This Issue

August 14, 1980

-

*

While Mellon’s book must supersede every other using Lincoln’s photographs, two books supplement it. Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose, by Charles Hamilton and Lloyd Ostendorf (University of Oklahoma Press, 1963, 409 pages, 535.00) is still in print. Its illustrations are clear, production modest, but it is a real omnium gatherum of family, friends, and foes. Lincoln and His America, arranged by David Plowdon (Viking, 1970, 352 pages, now out of print), contains some portraits and is interesting as documentary visual background of places associated with Lincoln. ↩