The so-called divorce between contemporary art and the public is not a recent development. Even fifty or a hundred years ago—and one could go back much further—there was an art for the few, for initiates. Leopardi and Baudelaire failed to win enthusiastic recognition in their lifetimes, and Manet had to slap one of his denigrators to turn him into his devoted servant and patron. Nevertheless, the initiated public in the last century was still a public, not a crowd of failed artists. Those who approached Parsifal and the Ring Cycle at the end of the nineteenth century studying ponderous “thematic guides” and following the leitmotivs with their fingers were lawyers, doctors, businessmen, not always failed musicians or poets.

Today, it is no longer so. Only the professional (whether he is failed or not), only someone “in the field” can hope to be, I won’t say entertained, but less frightened by certain forms of art which refuse categorically to take shape too visibly or perceptibly. Go and hear Arnold Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon: a man recites (bad) lines of Byron in stentorian tones. His cries succeed—and fail—at overcoming a sea of intestinal rumbling and dissonance which do not engender surprise so much as tedium, for the ear quickly becomes accustomed to the new tones, the new false notes. The piece goes on and on, but it does not live during the performance, nor can it hope to do so afterward, for it does not affect anything that is truly alive in us.

If this example doesn’t suffice, try reading an “uninterrupted” poem by Éluard, or worse, by one of his followers: you will find pages composed of strings of adjectives, hundreds of them, without a single noun; you will find poems in which each line moves on its own, has a meaning in and of itself, but is not linked to the others. The syntax is nonexistent, or it is confined to a level that is not only extra-logical but extraintuitive. At the most, it is sustained by a mechanical association of ideas. The reader has to create the poetry for himself; the author has not chosen for him, has not willed something for him, he has limited himself to providing a possibility for poetry. This is a great deal in itself, but not enough to stay with us after the reading. An art which destroys form while claiming to refine it denies itself its second and larger life: the life of memory and everyday circulation. I will try to explain what this second life of art is so as not to be misunderstood.

It is true: the work of art that is not created, the unwritten book, the masterpiece which could have come into being and did not, are mere abstractions and illusions. A fragment of music or poetry, a page, a picture begin to live in the act of their creation but they complete their existence when they circulate, and it does not matter whether the circulation is vast or restricted; strictly speaking, the public can consist of one person, so long as that person is not the author himself. Everyone is agreed on this point; one must not make the mistake of believing, however, that the appreciation, or consumption, of a particular expressive moment or fragment must necessarily be virtually simultaneous with its presentation to us, in an immediate relationship of cause and effect. If this were so, music would be enjoyed only in the moment in which it is played, and poetry and painting only in the moment when the eye rests on the printed page or the painted canvas. Once the cause, the narcotic, was gone, everything would cease; si charta cadit every glimmer of music or poetic feeling would necessarily vanish into nothing.

I do not say that many modern artists consciously make this artistic blunder; but I do want to point out that, whether consciously or not, a coarse materialization of the artistic act is at the root of many of today’s experiments. For this reason the second life of art, its obscure pilgrimage through the conscience and memory of men, its entire flowing back into the very life from which art itself took its first nourishment, is entirely disregarded. I am wholly convinced that a musical arabesque which is not a motif or “idea” because the ear does not perceive it as such, a theme which is not a theme because it will never be recognizable, a line or group of lines, a situation or a character in a novel which can never come back to us, even if changed and contaminated, do not truly belong to the world of form, of expressed art.

This second moment, of common consumption and even misunderstanding, is what interests me most in art. Paradoxically, one could say that music, painting, and poetry begin to be understood when they are presented, but they do not truly live if they lack the capacity to continue to exercise their powers beyond that moment, freeing themselves, mirroring themselves in that particular situation of life which made them possible. To enjoy a work of art or its moment, in short, is to discover it outside its context; only in that instant does the circle of understanding close and art become one with life as all the romantics dreamed.

Advertisement

I cannot see a line of indifferent mourners at a funeral or feel the Triestine bora blow without thinking of Italo Svevo’s Zeno; or look at certain modern merveilleuses without thinking of Modigliani or Matisse; I cannot contemplate certain caretaker’s or beggar’s children without having the Jewish baby of Medardo Rosso take shape in my mind; and I cannot think of certain strange animals—the zebra or the zebu—but the zoo of Paul Klee opens in me; I cannot meet certain persons—Clizia or Angela or…omissis omissis—without seeing once again the mysterious faces of Piero and Mantegna or having a line of Manzoni (“era folgore l’aspetto“) flash in my memory; nor—on a somewhat less elevated plane—can I consider certain episodes in the eternal war between the devil and holy water without hearing in my heart the enveloping feline mewing of the aria of St. Sulpice (as sung by Rosina Storchio).

So far I have given clear but perhaps overly obvious examples of what I mean by the circulation of an expressive moment or of an artist’s entire personality, summed up in his attitude; but it is not necessary to think of great names to explain the intensity of the phenomenon. There is no musical or poetic phrase, no painted or narrated character, who has not “taken hold,” who has not affected someone’s life, altered someone’s destiny, eased or aggravated someone’s unhappiness. Countless loves have been born in the trills of a vulgar little tune, countless tragedies have been scaled to the beat of a canzonetta, a Negro spiritual, or a line that “nobody else” (maybe not even its author) remembered any more.

Note that I don’t say art, and particularly music and poetry, must be easily mnemonic or memorable. This is an opinion concerning poetry which I have seen attributed to the Honorable Palmiro Togliatti, and when I read it I congratulated myself that I did not figure among the admirers of that aesthete (or that man). If what he said were true, Chiabrera would be worth more than Petrarch, Metastasio would be better than Shakespeare, and the poems in Alice in Wonderland would outdo all the odes of John Keats. What I do say is that any expression at all which has had a miraculous, liberating effect on someone—an effect of liberation and of understanding the world—has attained its goal and achieved Form.

I repeat that effects of this kind occur at a distance and are unpredictable. From time to time a great artist like Proust, obsessed by the petite phrase of Vinteuil (is he Franck or Gabriel Fauré?), can construct a whole world out of one memory, organize it, and bring it to its own particular modus vivendi; but we do not have to go so far for art to in rude on us and continue an absurd, incalculable existence within us. Nor would say that the second life of art is related to the objective vitality or importance of the art itself. One can face death for a noble cause whistling “Funiculi funiculà“; one can remember a line of Catullus when entering an austere cathedral or pursue a profane desire while associating it with a Handel aria full of religious unction; one can be thunderstruck by a caryatid of the Erechtheion while waiting in line to pay one’s taxes, or recall a line of Poliziano even in days of insanity and slaughter. Everything is uncertain, nothing is necessary in the world of artistic refractions; the only necessary thing is that these refractions be made possible, sooner or later.

Modern artists (I don’t mean all of them) who, through natural impotence or fear of walking down already traveled streets or out of a misguided respect for the ineffability of life, refuse to give it a form; those who deliberately exclude every pleasant sound from music, every figurative element from painting, every syntactical progression from the written word, condemn themselves to this: to not circulating, not existing for anyone. Since there is no possibility for a great communion between the public and the artist, they also reject the ultimate possibility of social significance which an art born of life always has: to return to life, to serve man, to say something for him. They work like beavers, gnawing at the visible, driven by an automatic impulse or an obscure need for an outlet or the need to build themselves a dark, ever darker, ever more hidden shelter. But they will never save themselves if they lack the courage to come into the light again and look other men in the eye; they will not save themselves if, coming as they have from the street and not out of the museums, they do not have the courage to speak words that can go back into the street, into circulation again.

Advertisement

(1949)

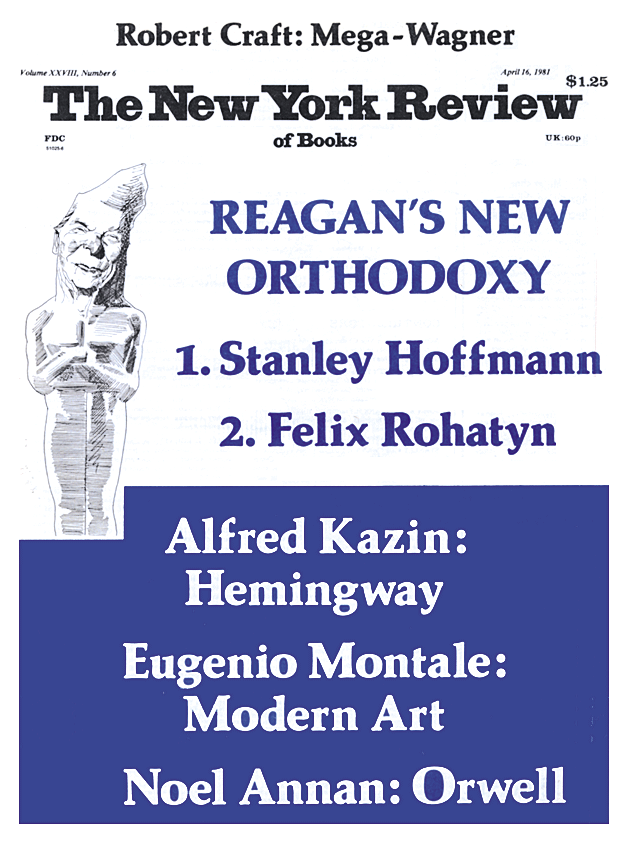

This Issue

April 16, 1981