In response to:

An Expense of Spirit from the May 15, 1980 issue

To the Editors:

I see that Martin Gardner is again using this popular literary journal as a vehicle to attack my scientific research that was reported in my Learning to Use Extrasensory Perception (University of Chicago Press, 1976) [NYR, May 15]. As a working scientist, I am committed to reporting and dealing with all of the facts in my studies, whether they agree with my cherished beliefs or not. Data is primary. Gardner, by contrast, apparently knows what’s true and false in some absolute way, so when inconvenient facts run counter to his beliefs he suppresses them or rationalizes them away. He knows that ESP is impossible, so when he is presented with evidence for it, he imagines some way in which the experimenters are fools, frauds, or both. Mr. Gardner doesn’t need actual evidence for this, his suspicions are sufficient. Most people would consider his casual and unsupported accusation of fraud against one of my more successful experimenters, Gaines Thomas (now a professional psychologist), as malicious libel, but I suppose Mr. Gardner believes he’s just protecting us gullible people from ourselves.

Gardner demonstrates how his absolute convictions allow him to take liberties to protect us from ourselves in presenting his apparently ingenious theory of a deliberate timing code used by a fraudulent experimenter being responsible for the high level of ESP shown in my study. He cites a publication of mine and my colleagues in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research (1979, 73, 151-165), indicating his familiarity with that Journal, but he does not mention several earlier communications of mine in that same Journal (see 1977, 71, 81-102; 1978, 72, 81-87; 1979, 73, 44-60) reporting precognitive ESP effects in the experiment he attacks, which could not be accounted for in any way by his time code model. Again I stress the obligation genuine scientists (and genuine critics) have of dealing with all the facts in a case, not just those they find convenient. Gardner has presented a clearly inadequate theory to a literary audience as if it were valid. The interested reader is invited to look at the above communications to ascertain the facts for himself. There are other distortions in Gardner’s article that I shall not bother to waste our time correcting here: they are, unfortunately, typical of Gardner’s writings on parapsychology.

When real scientists have criticisms of each other’s work, the standard procedure is to submit the criticisms to the appropriate technical journal. The submission is reviewed by other scientists for basic competency and relevance, and then published. I doubt that Mr. Gardner’s article would have stood up to this referring process in a legitimate scientific journal. A thoughtful reader might begin to wonder, then, why Mr. Gardner presents such a distorted and selectively incomplete picture of serious scientific research to the general audience represented by readers of this Review.

The implications of ESP for understanding human nature are enormous, and call for extensive, high quality scientific research. A recent survey of mine showed hardly a dozen scientists working at it full time, on a most inadequate budget of only a little over half a million dollars a year for the entire United States. The subject is too important and too under-researched to waste further time with pseudo-critics like Mr. Gardner who are covertly trying to manipulate public opinion, rather than contributing anything to scientific progress.

Charles T. Tart, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

University of California, Davis

Martin Gardner replies:

The funny thing about Tart’s letter is that he devotes most of it to attacking my motives but nowhere replies to its central point; namely that his first experiment had major flaws, he corrected some of them, repeated the test himself, got negative results, but has refused to retract his former sensational claims.

Precognition is the paranormal perception of future events. Psi-missing is making such a low score on an ESP test that it indicates paranormal inhibition. When Tart went over the data for his original flawed test of clairvoyance he found that subjects who did extremely well on “hitting” target cards scored significantly low on the next card to be selected.

There is a simple explanation. One of the grave defects of Tart’s first experiment was that his machine did not automatically record the numbers selected by his randomizer. When mathematicians found a strange absence of doublets (such as 2,2 or 7,7) in his target sequences, Tart explained this by saying that when assistants pushed the button to obtain a new number, and noticed that the displayed number did not change, they sometimes thought they hadn’t pushed hard enough, so they would push again before hand-recording the number! Clearly this freedom to keep pushing permits a sender to push again if the displayed number matches the subject’s last guess. Tart himself tells us that subjects almost never guessed the same number twice in a row. Knowing this, senders would have a strong unconscious urge to alter a random number if it matched the last guess. If done every time it would produce zero matching of guesses with +1 targets. Done occasionally it would significantly lower precognitive hits on +1 cards as well as raise hits on “real-time” targets. Tart has the chutzpah to claim that because he found some precognitive psi-missing in both experiments, this transforms the obvious failure of his replication into a whopping success! One’s mind reels at his capacity for self-deception.

There are two false statements in Tart’s letter. First, he accuses me of knowing ESP is impossible. I know no such thing. I firmly believe it is possible. I do not believe it has been demonstrated by evidence commensurate with the extraordinary nature of its claims.

Second, Tart says I accused his former assistant, Gaines Thomas, of deliberate fraud. I did nothing of the kind. I did show that Tart’s first experiment failed to guard against simple time-delay codes, and that in binary form such codes could operate without sender or subject being aware of their use. If there were collusion between sender and subject, which I doubt, the freedom to keep pushing the randomizer button also provides endless simple ways of beefing up a score.

When reputable scientists correct flaws in an experiment that produced fantastic results, then fail to get those results when they repeat the test with flaws corrected, they withdraw their original claims. They do not defend them by arguing irrelevantly that the failed replication was successful in some other way, or by making intemperate attacks on whoever dares to criticize their competence.

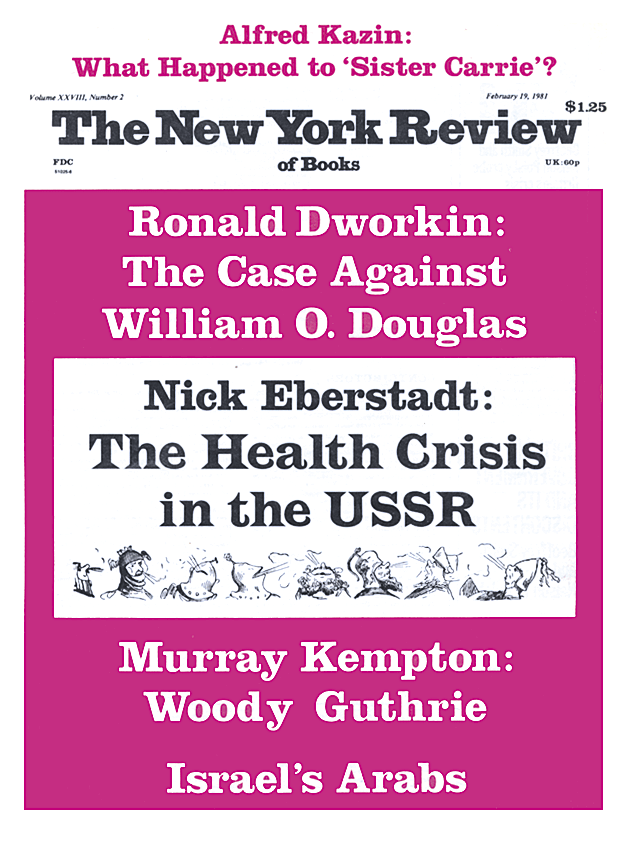

This Issue

February 19, 1981