Among those who regularly review the arts in America today, Arlene Croce is without peer. The present collection of eighty-three pieces originally published in The New Yorker, January 1977 to August 1981 and here slightly amended, includes at least one essay of enduring value, “News from the Muses” (on Apollo), and forty or fifty of exceptional interest. Ms. Croce’s criticism is distinguished by penetration and understanding of the subject, a large and novel scope of reference, and a creative imagination. Never “superior,” she does not display her erudition, though she has plenty of it, and to spare. An exception to Yeats’s “the best lack all conviction…,” she possesses a justified confidence in her own vision, powers of analysis, and judgments. She refers to someone as an “in-touch” person, and is one herself, which helps to account for her lively and enjoyable blend of the literary and the vernacular: plotzed, schlockier, glitzy, laid-back, ticklability, sleaze (as a noun), jocular-jock, and—surely with no double entendre—crotch-happy.

Dance, in this its heyday, is America’s most exportable artistic commodity, the one in which we have the most favorable balance of trade. No dance company in the world can hold a spotlight to our best, nor can any country rival the fecundity, variety, and abundance of our dancing ensembles. Britain may have the edge in sending us plays, Russia certainly has it in defecting performers, and the Far East is at least a match in breeding musical prodigies. But in the dance we are far ahead, the demand for it increases, and critical standards become ever higher. This phenomenon has given birth in Arlene Croce to a spokesperson well able to take its measure in every manifestation: ballet, modern and postmodern, experimental, tap, acrobatic, mime, ballroom, figure-skating, not to mention “the pitiless verve of contemporary Broadway.” Ms. Croce is a born theater critic, one who could easily move into the drama and movie reviewers’ chairs, as well as manage a column on the graphic arts, to judge from the way that she tweaks Rouben Ter-Arutunian for the most aureate of his set designs. And while not a musician, she reveals a sensitivity to music that must unsettle those equally untutored critics who have not for this reason been deterred from writing about it.

Only a decade ago, ballet reviewing was entrusted to the music departments of the press, but the expansion of the dance world has required specialization. What, then, are the tasks of its particular criticism? A symposium on the subject of writing about the dance, held at PEN headquarters in New York, December 6, 1978, elicited the following view from the choreographer Carolyn Brown:

I don’t believe the written word can recreate the experience of seeing any dancing. Should it try, is the question. It seems to me dance writing has to do something else.1

But the written word cannot convey the experience of any of the arts except the verbal. That none of the panelists, of whom Ms. Croce was one, proposed “something else” is hardly surprising. After all, the dance critic, unlike his colleague in music, lacks such tangible tools as recordings and printed scores, and even when the ballet repertory has been filmed, the videotapes cannot be similarly definitive. Individual dance performances differ more radically than musical ones do, thanks in part to music’s more highly developed notation. Even the most self-indulgent conductor cannot totally override Beethoven, and the differences between renditions of the Brahms concerto by two equally capable violinists will be less significant than those between Baryshnikov and Martins in a narrative role. The dance critic, it follows, must be sensitive to the most subtle differences effected by casting,Arlene Croce herself remarks this and more:

Since ballets have no existence apart from performance, it’s inevitable that, like dancers, they change over the years.

Dances are perishable goods….

Dance is a present-tense art form with no precise way of recalling or predicting itself.

Dance action, if not the experience of the dance, can be described verbally, and much of the critic’s effectiveness lies here. The vividness is generally proportionate to the lapse of time between reading the review and attendance at the performance (though the ballet that Ms. Croce most clearly revived in my memory is Calcium Light Night, which I last saw at the New York City Ballet four years ago). In my case, the effect of words is usually limited to reminding me of positions and poses with specific performers executing them. But descriptions of movements in succession fail to form trajectories: I can see stills, but continuous movement only with rare exceptions. Thus some of the images in the following excerpt take shape in my mind, but I cannot link them:

There is a brisk fugue for the corps, flanked by two solos for the male star. In the first we recognize an elaboration and mobilization of the simple preparatory stretch and point exercise with port de bras that had occurred at the outset of the theme. The dancer swings from side to side, and then from front to back (renversé in attitude) in low vaults through space. A flurry of pirouettes decelerates in a seamless return to the theme gesture.

The passage is torn from its far more technical context, and since I am not familiar with the ballet under discussion, the words do not make a picture for me (as the figured bass “A-flat I, IV, d0Vu7,I-IVu7, Vu7, Iae” would probably not suggest the first phrase of one of Bach’s best-known chorales to anyone except a professional musician). Incidentally, I doubt that choreography can represent much more of fugues than the exposition of their subjects, though parallels for stretti and other devices might be realized by color and lighting.

Advertisement

Although Arlene Croce’s book will mean more to those who already know the dances that it discusses, it can be read with pleasure by anyone interested in the art, or if not that, in a good writer with a first-rate mind. Understandably, a volume of reprinted reviews, some of them updated reports of the same work, and including such vital statistics as the names of the orchestra conductors, is not for reading straight through. Nonetheless, the dross is minimal.

Most of the essays are cast in a format that begins with an apothegmatic pronouncement, some good (“Book musicals are dying, revues are dead”), others less so (“In choreography, if you can’t be a genius, then you must be ingenious”). The arguments depend on comparisons, hence the frequency of “sounds like” (a Morton Feldman score sounds like “someone playing slow organ chords at night in a basement two houses away”), “looks like” (“[Heather] Watts, in her crimson unitard sheared off at calf and bustline, looks like a thermometer”), and “as” (“[Cynthia] Gregory was as severe as the edge of a knife”). Some of these metaphors are dazzling, but not the one that tells us a certain dancer “gave us moments of illumination as wide and blank as fate.” We wish the sentence had stopped sooner: the theory that “fate is wide and blank” (hardly my conception of it) takes us off on a tangent.

Occasionally, too, Ms. Croce strains for paronomastic effects that might better have been avoided, such as “double and triple canons cannonading between piano and orchestra,” and, writing of Merce Cunningham, “the French are temperamentally non-mercist (non, merci).” But, then, I don’t care for the echoic, even “Le Monocle de Mon Oncle.”

Croce’s best epigrams, maxims, precepts, and distinctions seem to form themselves:

Having pursued a mixed objective, he comes away with mixed results….

One must try to distinguish history from the wistful preservation of a legend….

Slow is a dancer’s idea of serious, but the danger is that her accent will smear, her line turn ropy.

(“Accent” and “line” subtly invoke a parallel with verse, in which, generally, the pace retards with the intensification of thought.)

Style [is] a system of preferences….

[Baryshnikov’s] Orpheus is a romantic hero, a protagonist. Balanchine’s is a disinterested artist….

The ritualistic repetition [in] postmodernism…sentimentalizes the process of repetition by attributing to it more power than it possesses.

Dance impetus that comes from nothing more than mood isn’t interesting enough to sustain a whole ballet….

…obscenity of every description is one of the two great driving forces behind the ballet; the other is the belief in forgiveness and salvation.

Croce’s wit can be devastating:

Every time I see the Béjart dancers, they’ve lost more muscle tone and added more makeup.

What happens next in one of [Grigorovich’s] ballets is generally what happened a minute ago.

In the innocence and shamelessness of his ideas, [Valery Panov is] under the divine protection of bad taste.

At peak moments in a performance [the benefit audience] will begin perusing its program to see why it came.

I find myself not only concurring with most of Arlene Croce’s judgments but also discovering that we are attracted to the same women, the “coldly enticing” Diana Adams; Suzanne Farrell, who is “sexually very potent on the stage”; Twyla Tharp, who has “beautiful, sexy legs”; Merrill Ashley, who has “lovely” and “voluptuous” ones; and Patricia McBride, who, in Voices of Spring, “looks lusciously round and rosy.” (Yummy.) The description of a Zobeïde, “legs braced in deep fondu, body arched backward in a swoon of anticipation,” is positively venal (but doesn’t “fondu” refer to only one leg?). Croce can pull a leg, too (a “pure danseurnoble type [dances, at times] as if he had all that and more to uphold”), while offering valuable comments on the relationship of sex, dance, and dancers. Thus, so I believe, she correctly perceives that Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet “may be the only ballet in standard repertory that homosexuals can identify with emotionally without distortion.” Obviously this depends on the staging—the way the San Francisco Ballet costumes “the boys in tights and codpieces”—but to Croce’s several additional reasons, one might add that the heterosexuality in this play is on the puppy-love level anyway.

Advertisement

The New Yorker critic supports Vera Krasovskaya, Nijinsky’s biographer, in her interpretation that his role as Petrushka was a sublimation of his reallife humiliation by Diaghilev. Going further, Croce sees Nijinsky’s choreographic creations as a sexual autobiography, progressing from the “orgasm, self-induced” of Faune, to the “consciously manipulated” one of Jeux, and the “communal seizure” of Sacre. But her conclusion that Diaghilev’s “personality as we know it is more Noël Coward suave than John Barrymore unctuous…” makes one wonder if “unctuous” could ever have applied to Diaghilev? Not as he appears in Stravinsky’s archives, where the most frequent descriptions of his character are “liar, cheat, false friend, and insanely jealous.”2

I agree—and think Stravinsky also would have—with Arlene Croce’s verdict that Paul Taylor’s Sacre is the ultimate post-Nijinsky staging. If it serves no other purpose, Taylor’s should protect the piece from ravages of the Béjart type for at least a generation. True, it is the four-hand piano version which evokes the silent-movie atmosphere for this hilarious drama of living bas-reliefs: Taylor’s high jinks are inconceivable with the mammoth orchestra. Nevertheless, the music retains some of its apocalyptic power in any form, and a measure of the imagination of this choreographer is his realization that bloody murder had to be committed, even à la Bonnie and Clyde. My only doubt is Croce’s statement that Taylor heard the music as “automatons chugging to their doom in a deterministic universe.” Mightn’t he simply have seen the comedy in the belly of the tragedy?

Croce’s intuitive sense of the relationship between music and choreography is almost always helpful, even when translated to visual terms:

Having frozen his dancers to shivering tremolos, he does not unfreeze them when the music melts into droplets of pizzicati.

She correctly deduces that in Apollo Stravinsky may not have intended to have a lute as a stage prop, since he did not include “its sound in his orchestration.” She notices that when the choreography responds wrongly to the music, we are “getting a statement about [the choreographer’s] uncertainty as an artist.” Though she may be right in her assertion that “most people identify a song’s meaning through its lyric, not through its music,” her example seems mistaken: “Irving Berlin’s ‘Blue Skies’ is a…’happy’ song, even though its music is a dirge.” A dirge? She is more certainly on target when writing that “the pounding disco beat is of no use to a choreographer,” and that the disintegration of the beat in present-day “pop” is a real obstacle:

Pop used to be made for dancing. Since it became a troubadour’s art form…harmony has become more important. Dancers are looking for a releasing rhythm or a good tune, and the music just keeps on changing chords.

Not that many chords, either. Of a David Tudor score for a Merce Cunningham event, she asks,

How can you watch a dance with V-2 rockets whistling overhead?… Some of the dissociated-sound scores that Cunningham uses are more interfering and dictatorial than planned settings would be.

Other Croce comments on music deserve mention, but first the lack of one: she never refers to the disruptive timing of so much New York City Ballet applause, revealing the audience’s insensitivity to music. Musician-readers might wonder why she calls the viola the “testiest of string instruments”; Balanchine’s Sinfonia Concertante, one of his greatest masterpieces, is partly a work of homage to the beauties of the only feminine-gender string instrument in the modern orchestra. Yet her best remarks more than atone for a questionable few. Satie’s Relâche “is a relic, not a classic,” she writes, and “Verdi’s La Traviata…lavishes great music on a story that should have waited for Puccini.”

Ms. Croce devotes space to the use of words in dance pieces, writing of Gertrude Stein’s text for A Wedding Bouquet:

Language so majestically impartial has power in the theatre—maybe only in the theatre.

Nothing is said, however, about the independence of verbal rhythms, a large ingredient in Stein’s hypnotic language in this ballet. In an offering by Cage and Cunningham,

the words and dancing [were placed] on separate planes, and the result was that Cage distracted us every time he opened his mouth.

The problem is that

either the dance reports what the words are already saying or it strays so far from the verbal meaning that I can’t guess what connects the two.

George Balanchine is, of course, the hero in Arlene Croce’s chronicle. She hangs on his words as well as his deeds, reporting on a conversation with the artist in his later years: “It’s disappointing to get stainless steel when you’ve been expecting old gold.” As for the young Mr. B.’s daredevil Michelangesque creation-gesture in Apollo: “Only geniuses are really young at twentyfour; the rest of us are just childish.” For this reader, her most absorbing discussions are of the choreographer’s revisions and changes in his classics throughout the years—in the Mozart Divertimento in B-flat, for example, music that now seems to me incomplete without the choreography. When Balanchine reworks traditional ballets, the audience demands that he express a “contemporary point of view.” She remarks:

The steps may not be Petipa’s but their quality of expression is. And is Balanchine’s at the same time. For a comparison, see his Swan Lake, in which both the surface and the depths of an old ballet have been organically reconceived.

In her assessment of the City Ballet’s recent Tchaikovsky Festival, Croce is forced to distinguish House of Balanchine from Balanchine, comparatively little of real value by the master having emerged. Her shrewdest comment on the occasion pertains to the dependence of the music, as choreographic material, on the visual arts, for “Tchaikovsky cannot be expressed in absolutist, abstract terms.” Because of this, perhaps, her article focuses on the composer’s personality, and her remarks on him are based on Constant Lambert’s rather shopworn distinction between the side which “cries for the moon” and the one which is “content to gaze at its beauty.” But can it be said, tout simple, that Tchaikovsky “really was sacrificed on the altar of social hypocrisy” without suggesting that more profound inner causes were also responsible for his suicide?

Finally, let me say of Arlene Croce as she says of a dancer:

We recognize the analytical powers of an artist [who is aware of] the most delicate emotional distinctions in movement and makes us see them, too….

She loves the dance, and in her patient, close attention to it conveys this love to us. What she writes about the art will affect our thinking for a long time to come.

Toni Bentley’s diary of a recent threemonth season dancing in the corps of the New York City Ballet is a minimarvel, impossible to put down. One wants to say of the book, as she exclaims of a backstage incident in the State Theater, “How delightful, how refreshing!” When she tells us that “I am twenty-two and feel that my career is at a standstill,” we feel her age, not ours.

I cannot comment on Ms. Bentley’s abilities as a dancer, even in potential (she pokes fun at the NYCB for the way it regards all less-than-luminaries as “potential”). But I am certain of her talent as a writer. Despite George Balanchine’s exhortations not to think but to do, she cogitates as she dances, and knows that the writing of this book contradicts the total dedication required of NYCB members. But then her subject is the war between the demands of a career as a dancer and the living of a normal life. Ballet schools, she suggests, should devote “one hour a week for learning about life, the world, and other possibilities.”

Toni Bentley is acutely self-aware without being self-obsessed. She can laugh at her amour-propre:

I refused to replace a girl in what was originally my part…and was taken out. Then they asked me to replace her when she was ill. I refused, so I don’t dance and have loads of self-respect. I can envision the day when one has nothing but self-respect.

Her accounts of Mr. B—in this book the hypocoristic indentification is preferred—are keenly observed and laconically conveyed:

He is old, gray; he squints and arches his head upward to make her analyze herself. He rises and jumps around, showing her where to go, how to do it. “Where did you learn that? Did you go somewhere?”

He is already fearful and suspicious that she will desert him and go to another for help. She assures him that no one taught her, she just did it alone. She has taught herself. He will change it.

All eyes focus on the two, moving from Darci [Kistler] to Balanchine, from Balanchine to Darci. Everyone wants to know what he thinks of her every step. The eyes flit back and forth, back and forth, trying to correlate and imagine their two minds. It is romantic, Darci at sixteen, Balanchine at seventy-six, coaching. It is beautiful to see.

As a dancer’s-eye portrait of the choreographer, a divinity to Ms. Bentley as well as, apparently, to everyone else in the NYCB and to uncounted other ballet lovers in the world beyond, the book is invaluable.

In Ms. Bentley’s paean, Mr. B. is:

…our mother, our father, our friend, our guide, our mentor, our destiny….

He knows all, sees all, and controls all. … He seems to believe in self-discovery, and at times that is hell—when one knows that he knows but will not tell…. His power over us is unique….

She tells us “how wonderfully human he is,” not lacking “anything human, spiritual, emotional, or practical,” and how direct and simple. But to dance for Balanchine is to give one’s utmost and all of the time. She repeats his carpe diem philosophy: “What are you waiting for? What are you saving for? Now is all there is.”

Elaborating on the differences between the performer and the creator, she envies the latter his choice of “how, when, and where to present [his] vision” and “the privacy [he] is allowed, and allows himself.” In contrast, “we must be like trained animals…be spontaneous in public in front of three thousand pairs of eyes,” though one pair, Mr. B’s, sees “more than all of the others put together.” The dancer’s share in creativity comes through the “direct connection to the heavens and the gods—Balanchine and Stravinsky received their talents and visions from God…we are the paint in the pot.”

Toni Bentley reveals what goes on in her mind as she awaits the outcome of an audition, or while she is on stage dancing, or lying on the floor looking in the direction of the audience or at the ceiling, or standing in the wings and watching one of her heroes (Suzanne Farrell and Peter Martins). The young author spares us none of the details of physical, psychological, and social torture prerequisite to her profession, the bleeding toes, swollen and distorted feet, starvation (she craves food more than increases in salary), and exhaustion (the prostrate, panting, and perspiring bodies in the wings), of holding poses beyond the outer limits of endurance, of the tedium of costume and makeup changes, and, so far as the audience is concerned, of dancing in a vacuum, though, at the same time, applause is the dancer’s only “feedback.”

As I have already said, Toni Bentley is a skillful—and an ingenuous but not naïve or sophomoric—writer. If she has lingered over a mot juste, her effort is concealed from the reader:

I have a friend, another dancer. She is in the company. A girl, a woman, maybe, at least on the cusp of transition.

Describing a new girl in Rubies who started dancing sixteen counts too soon while the others were stationary, Ms. Bentley says that “she looked like an escaped jumping bean.” I felt like one, too, at least for some of the time while reading this book.

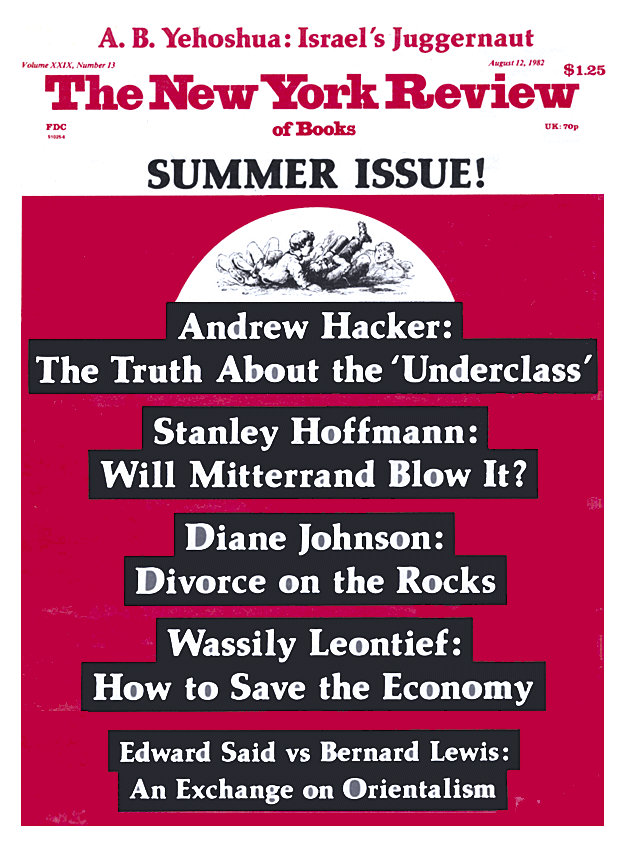

This Issue

August 12, 1982

-

1

Reprinted in Ballet Review, Volume 7, No.4, 1978-1979. ↩

-

2

This material, soon to be made available, unfortunately does not contain the intimate memoirs of Nijinsky that Stravinsky began to write in 1957—until Doubleday prematurely showed the first paragraphs to Romola Nijinsky. Under threat of a lawsuit, the composer abandoned what would have been a profound testament of friendship for the dancer, and something of the opposite for the impresario, with whose name Stravinsky’s is as permanently linked as are their bones in a Venetian cemetery. Having been Adolph Bolm’s neighbor in California for three years, and never finding him or Stravinsky reluctant to discuss Diaghilev and Nijinsky, I can only regret that the popular use of the tape recorder came so much later. ↩