Out There, November, 1982

Sculptors who accept commissions for work in public areas have been wearing bulletproof vests. “That’s for after it’s in place and unveiled,” Billy DiCaro said recently. DiCaro was awarded his contract over the objections of most of the members of the Indiana Art Board (IAB). By some fluke the chairman of the board, Ruth Sarkington, had been given a “kill” right in the contract and so she was able to overrule the board and appoint DiCaro. Sarkington (since replaced) said a lot of members of IAB were composers of opera and, to quote, “while there is a renaissance in opera areas in Indiana, I don’t see what that has to do with the renaissance we want in Wabash Park.”

DiCaro’s sculpture is a piece with very urban structural connotations. He has eschewed the Indiana idiom as condescending and out-of-time. He has produced a long, stone bench, decorated with Italian tile which recalls the bench in Grant Park on Riverside Drive in New York. So that the public will not sit on the bench, which is visual and not to be seen as a functional ornament, bronze figures are placed at intervals. Next to the most prominent of the figures there is a sculpted shape that suggests in strong, formal terms a paper bag with a whiskey bottle in it. This orientation caused an uproar in the pleasant, “more or less” puritanical midwestern state.

Meanwhile, under a privately endowed public space project, a sculpture by Bonita Salt is planned. Hers is to be a soaring, abstract design of metal used both austerely and indigenously. Salt complained that her projected work, which is “very site-situated,” is violated by the DiCaro bench, “which might be anywhere and would be better nowhere.” DiCaro rebutted, “Speaking of nowhere….”

—Art Wine

Big Indeed in the Big City, November, 1982

Batti and Bardi have speeded up the momentum in the traffic-clogged New York Art Scene. These two European artists, with of course the notable, magical Borolini (the three of them known in the inventive, opaque New York street language as the ABCs) have flooded our shores with a rich, lush Mediterranean expansiveness. Imagine, the downtown galleries and the buyers are saying, the very clever Europeans, bombed on Manhattanism and processed items from the action-school of New York, didn’t know what was under their noses. That is a simplification of process. The expansiveness of the New York School was another kind of out-reach altogether. That and the profoundly indigenous Pop Art were an expression of the postwar American era of economic glut, in which waste and a no-holds-barred possibility exploded in a brilliant Paradise Enow surfeit that was the envy of the Second and Third World. Not to confuse things, Paradise Enow is still valid as an esthetic, if only as a dialectical comment upon The Slump, as a new group of exuberant young artists call themselves.

For the Europeans—which, indeed, indeed, includes the new Germans working under the shadow of the really awful legacy from their parents in the 1930s—the classical European command of the staggering images of Art History itself is being re-commanded and re-assembled in mostly figurative language, stereophonic in its inclusiveness and relentless spread. Borolini, in particular, explicitly refuses to deny his absorption of Piero, Pisanello, and also the interesting contemporary Italian radical, Feltrinello. “Why should I?” Borolini said recently at a reception at the Daisy Crockett Gallery. “Sono Italiano.”

All of this has not been lost on our own Americans such as Casalle and Gieseking. Gieseking is downright rude about previous Reductionist esthetics. “We will rebuild from the rubble and they better believe it.” However, Gieseking, who insists he is American-born, is somewhat privately troubled by the roll-over of the Europeans. They are his friends; he admires them as colleagues in the post-modernist expressionist revolt. Indeed he sees them perhaps as a validation somewhat and so, according to rumor, does Casalle, the increasingly selling master of his rich, interestingly unsynthesized tonalities. On the other hand the trade balance bothers Gieseking at this point in our “recovery.” He would not like the Europeans—including the Germans at the Hamme-Westphalia Gallery—to dominate the scene and further depress our native manufactures, along with automobiles and Sonys. He says, ruefully, “Great artists, but you know they have their deals—or rather, dealers—and their own rich people over there.”

—Roberta Crowd

London and the Damn-Right New York Show

One of the leading British old-school critics said recently, “Insofar as graffiti is concerned, the subways of Europe are a veritable desert of inanition. Needless to say, the Russians are out of it, as usual. The same old Soviet dark ages. Bloody fools.”

Another younger, red-brick critic said, “I can’t tell you what it was like having Fred Waring here. It was, I tell you, what you people call a ‘learning experience.’ Waring, insofar as we here in Britain look at it, has it all. White, and I must say amazingly cleancut considering the medium, you know.”

Advertisement

When I was talking to the British critics, I advised them to wait until they caught up with Little Angelica, absolutely fantastic. One of the first women, just a girl really, to storm the subway parking lots at 2 AM. It should be pointed out, for the sake of history, that her real predecessor was the brilliant Rosa Bontemp, daughter of recent Haitian refugees, among the last actually to be let in. Rosa never made the lots. She said she wasn’t oriented enough just yet. And she also added generously, “I am bigger than Little A, but she is bigger than me.”

Waring has turned out to be a marvelous expositor of his own Graffiti Art and, of course, that of the rest of the group. “It was the final blow-out, showing on the gallery walls, being paid instead of getting a summons and going down to the filthy city jails.” Waring’s imagery is pretty benign; it’s the black spaces he finds when the ads are being changed that is revolutionary. As he said, “Commerce stops to take a leak and art moves in.”

Another young graffiti artist has had to move out of LA because the subway situation is really primitive there. He misses the sun, but says, “It’s my time. Darkness and noise are the symbols of today.” La Ventura, a vivid Puerto Rican subway artist, is also in London for the show. His work is undergoing a change, but as a basically conservative artist his message still is: “Don’t cool down, New York. I’ll never give up the spray can for some kid crayon.”

Of course, here in London if anybody can put Waring back in the pits, not that anybody actually wants that, it is the appearance of The She. A sensation, yes. There’s been so much in the art press I’ll just reprint from the tape I made with the BBC.

BBC: The She is a multi-media personality par excellence I believe. Art, a kind of poetry, music, stage performance, records. Of course, multi-media is not new for a strange kind of personality. We’ve met them before in Europe.

Me: The old European multi-media personality was a neurosis of middle-class people, those who could afford psychoanalysis. But with the The She, there is no middle-class and, for those there are, the hope is just about in dissolution. Basically, in The She’s conceptualism nobody is lying down and nobody is sitting up over you while you are lying down.

BBC: The She’s performances, on the wall of the gallery, on the stage, on her records have been of tremendous importance to the young New York artist. Right?—to use an Americanism.

Me: The most.

BBC: Tell me about Southwest, her amazing neo-minimalism.

Me: Well, she stands in front of this map collage. Alaska on the right and Texas and all of that on the left. She talked about her road maps recently at the King Solomon’s Mines Gallery.

BBC: I missed that interview.

Me: A lot of people did. But what she basically communicated was that you see this map and there’s a little number 10 on a wavy line. It’s supposed to connotate 10 miles to Houston, but on the map it’s only 1/10th of an inch or something if that. Now, if a car is traveling south at 1/10th of an inch per mile how long does it take to get to Houston?

BBC: Not a clue on this side of the water.

Me: Right.

BBC: When The She performs she works with her own conceived instruments?

Me: That’s it. The most unusual is a quote from Duchamp’s bicycle wheel. You spin the wheel and due to the tension in the spokes you get a sound somewhere between the hum of cars in the Lincoln Tunnel and a sort of high-pitched tremor.

BBC: Can the audience hear it, so to speak?

Me: Probably not without the kind of undivided attention The She herself has.

BBC: One more before cut-off. Some critics think she derives from the incredibly wonderful admixture of learning, quotation, and bald originality found in Pound’s Cantos.

Me: All I can answer is that she once said about Pound: I love his weight.

—Snippets

On the Wall: Also Noted. November, 1982. Group Show

It is good news to note that drawing is back in style after the deconstruction of the 1960s and the barest reformulated suggestions of it in the 1970s. Of the young artists shown here, Jack Smither and Jane Reens are the most comfortable in the form. Reens has not quite mastered her broken-line esthetic, but the feathery daring of her bulky nudes shows that the conception is not preliminary but has reached a fully achieved stasis. Smither abandoned drawing at the beginning of his career—in favor of painting—and his first notable exhibition at the age of 19 showed almost no trace of it. Now, at 25, he is splashing drawing all over the heavy handmade paper he employs with a real punk abandon. One of the most intriguing drawing results, titled C, is a loose, almost hallucinated collage of tightly rolled dollar bills, beautifully drawn noses and pastel glittering eyes.

Advertisement

—Jennifer Caine

Dick Hoare

Two years ago, Hoare made his remarkable debut with a show of impeccably coarsened oils titled “Days of Girls of the Night.” The documentary aspect of the presentation was overruled by a surrealist contemplation that trans-figured the street material. His new show works with the same promising, observed neo-realism. Especially fine is Maggie, a cooly conceived portrait of a young girl in hot pants and halter standing in a dark alley reading The Book of Kells with a little flashlight. If she calls to mind Hopper’s usherette, the quote is intentional, but with a difference.

—Jackson Pickupp

Cynthia Ozaka

For Ozaka, a conceptualist, working with specific conceptions, visual perception is a matter for constant experimentation. The viewer is also asked to experiment and to test himself in as uncompromising a way as the artist. This is what you might call Risk itself, but in these often geometric forms, with their delicate colors extending to the gallery wall, intellectual and painterly emotional contrast is achieved. Creating her maze-like intentions as she goes along, the astonishing thing is that she emerges from the maze without corrupting the essentially pure spatial geometry, which might in a less rigorously planned execution have simply combusted.

—Jonathan Orestes

F. Marian Crawford

Now that winter is upon us there are a lot of summery photographs around town. This is to be expected when you consider the intense, time-consuming attention to perfect prints the young photographers go after. F.M. Crawford’s shell photographs combine the extraordinary visuality of the eternal shell with compositional concerns drawn from painting. The cone-shaped “turban” shells lined up on the beach give a striking pointillist effect. On the other hand, in the Polaroid SX70 selections there are moments of captivated social realism. One in particular stands out—a shell bracelet around a hairy ankle that manages the vivid look of a live crustacean.

—Eugene Boynton

—Elizabeth Hardwick

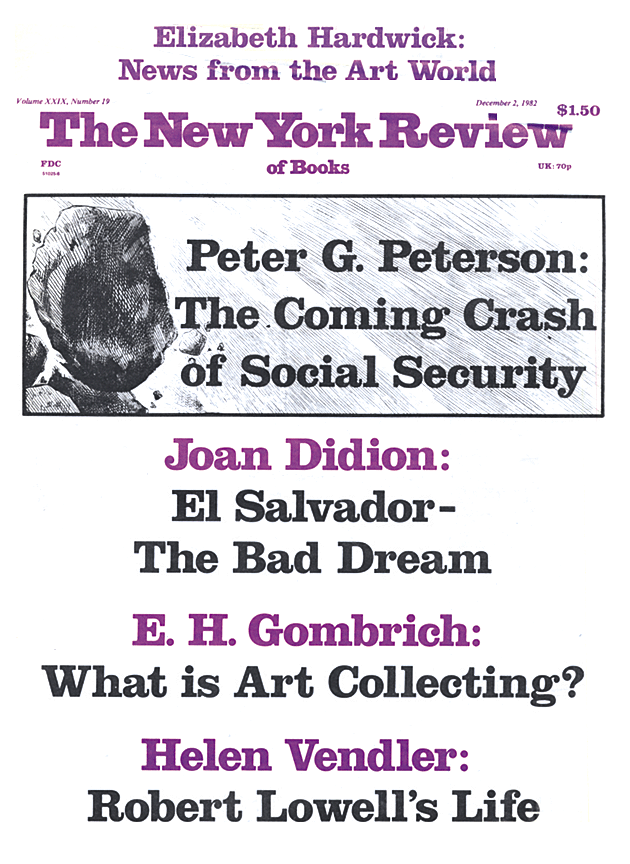

This Issue

December 2, 1982