Ezra Pound once divided writers into carvers and molders. The molders—Balzac, Lawrence, Whitman—work fast, not much worried by detail or repetition or precision, impatient to get down the shape and flow of their inspiration, while the carvers—Flaubert, Eliot, Beckett—work with infinite slowness, painstakingly writing and rewriting, unable to go ahead until each phrase is balanced, each detail perfect.

Cynthia Ozick is a carver, a stylist in the best and most complete sense: in language, in wit, in her apprehension of reality and her curious, crooked flights of imagination. She once described an early work of hers, rather sniffily, as “both ‘mandarin’ and ‘lapidary,’ every paragraph a poem.” Although there is nothing stiff or overcompacted about her writing now, she still has the poet’s perfectionist habit of mind and obsession with language, as though one word out of place would undo the whole fabric.

She has, in fact, published poems, but the handful I have read seem a good deal less persuasive and subtly timed than her prose. Listen, for example, to the narrator of “Shots,” the best story in her new collection. She is a professional photographer, hovering on the edge of infatuation with gloomy Sam, who is an expert on South American affairs, heavily but uneasily married to a paragon. She and Sam have been brought suddenly together when a simultaneous translator at a symposium Sam is addressing and she is photographing is murdered by a terrorist who can’t shoot straight:

The little trick was this: whatever he said that was vast and public and South American, I would simultaneously translate (I hoped I wouldn’t be gunned down for it) into everything private and personal and secret. This required me to listen shrewdly to the moan behind the words—I had to blot out the words for the sake of the tune. Sometimes the tune would be civil or sweet or almost jolly—especially if he happened to get a look at me before he ascended to his lectern—but mainly it would be narrow and drab and resigned. I knew he had a wife, but I was already thirty six, and who didn’t have a wife by then? I wasn’t likely to run into them if they didn’t. Bachelors wouldn’t be where I had to go, particularly not in public halls gaping at the per capita income of the interior villages of the Andes, or the future of Venezuelan oil, or the fortunes of the last Paraguayan bean crop, or the differences between the centrist parties in Bolivia and Colombia, or whatever it was that kept Sam ladling away at his tedious stew. I drilled through all these sober-shelled facts into their echoing gloomy melodies: and the sorrowful sounds I unlocked from their casings—it was like breaking open a stone and finding the music of the earth’s wild core boiling inside—came down to the wife, the wife, the wife. That was the tune Sam was moaning all the while: wife wife wife. He didn’t like her. He wasn’t happy with her. His whole life was wrong. He was a dead man. If I thought I’d seen a dead man when they took that poor fellow out on that stretcher, I was stupidly mistaken; he was ten times deader than that. If the terrorist who couldn’t shoot straight had shot him instead, he couldn’t be more riddled with gunshot than he was this minute—he was smoking with his own death.

The writing is intricate and immaculate: a poet’s ear and precision and gift for disturbing image—“it was like breaking open a stone and finding the music of the earth’s wild core boiling inside”—combined with the storyteller’s sense of timing and flow, the effortless shift between the colloquial and the allusive, the changes of pace and changes of tone—her subtle, passionate ironies, his nagging self-pity—the paragraph balancing gradually, logically, to its climax.

Logically: Miss Ozick is very much a New York intellectual, like Puttermesser, the heroine of two of the five stories in Levitation, who “had the habit of flushing with ideas as if they were passions,” and whose idea of paradise is an eternity of books and candy:

Ready to her left hand, the box of fudge…; ready to her right hand, a borrowed steeple of library books…. Here Puttermesser sits. Day after celestial day, perfection of desire upon perfection of contemplation, into the exaltations of an uninterrupted forever, she eats fudge…and she reads. Puttermesser reads and reads. Her eyes in Paradise are unfatigued.

Puttermesser has a first name—Ruth—but only her mother and her lover use it. To Miss Ozick, Puttermesser is simply Puttermesser, a warrior of the word and the idea, though by profession a lawyer who has graduated from the back rooms of a smart Wall Street firm to the labyrinth of New York’s civil service; she is assistant corporation counsel in the Department of Receipts and Disbursements. She is also clever and studious and plain. Her best feature is her nostrils—“thick, well-haired, uneven…the right one noticeably wider than the other”—and she is attracted to her lover, Rappoport, because he too has an eloquent nose “with large deep nostrils that appeared to mediate.” In Miss Ozick’s stories, glamour is never physical; it is in the mind and in the style. Puttermesser hates the Breck shampoo girl “with a Negroid passion.”

Advertisement

I suspect Miss Ozick would also claim that glamour is in the inheritance. She is obsessed with Jews and things Jewish. At her first appearance Puttermesser is learning Hebrew from her great-uncle Zindel; or rather, she is learning Hebrew and chooses to imagine that her teacher is her great-uncle Zindel who died, in fact, four years before she was born:

But Puttermesser must claim an ancestor. She demands connection—surely a Jew must own a past. Poor Puttermesser has found herself in the world without a past. Her mother was born into the din of Madison Street and was taken up to the hullabaloo of Harlem at an early age. Her father is nearly a Yankee…. Of the world that was, there is only this single grain of memory: that once an old man, Puttermesser’s mother’s uncle, kept his pants up with a rope belt, was called Zindel, lived without a wife, ate frugally, knew the holy letters, died with thorny English a wilderness between his gums. To him Puttermesser clings. America is a blank, and Uncle Zindel is all her ancestry.

It is not so much a story as a statement of faith, ending in a challenge: “Hey! Puttermesser’s biographer! What will you do with her now?”

We find out in the last tale of the collection, in which once again Jewish lore and Jewish folk magic come to the rescue, though this time not of Puttermesser but of the city of New York. A new administration has been voted in and Puttermesser is ritually knived, demoted, then fired. The same night Rappoport walks out in a huff when she insists on finishing Plato’s Theaetetus before making love. Half dreaming, half awake, she makes, instead, a golem, a Hebrew version of Frankenstein’s monster.

The original golem, as the learned Puttermesser knows well, was created by “the Great Rabbi Judah Loew, circa 1520-1609,” and was the savior of the persecuted Jews of Prague. Her own golem—a female who insists on being called Xanthippe, after Socrates’ shrewish wife—does the same for New York: she gets Puttermesser elected mayor and turns that sophisticated urban war zone into an earthly paradise. But not for long. The golem, growing daily larger in size and appetite, discovers sex. She terrorizes the male population, order disintegrates, Puttermesser is disgraced. In the end, she destroys her creation, the scheming exmayor is re-elected, din and savagery are restored.

It is a witty, elegant, and invigorating fable, but Miss Ozick is not kidding. For her, redemption is racial and religious: it lies in Jewish conscience, Jewish history, Jewish magic, and the Hebrew language. In the preface to an earlier book, Bloodshed, this most subtle of stylists paradoxically confessed to a profound unease in writing English while remaining so intensely Jewish in her apprehension of the world:

Though English is my everything, now and then I feel cramped by it. I have come to it with notions it is too parochial to recognize. A language, like a people, has a history of ideas; but not all ideas; only those known to its experience. Not surprisingly, English is a Christian language. When I write English, I live in Christendom.

But if my postulates are not Christian postulates, what then?

She had no answer at the time and probably has none still. Certainly, she is too authentic an artist to go running after immigrant rhythms or Hester Street kitsch. The English she writes is pure and controlled and, in a wholly twentieth-century way, classical. Yet she seems, nevertheless, to hanker after Bashevis Singer’s shtetl with its superstitious peasants and dybbuks and what she has recently called “the centripetal density and identity of a yeshiva society.” So Puttermesser, who reads everything, prefers Theaetetus to sex, and is ambitious to “learn about the linkages of genes, about quarks, about primate sign language, theories of the origins of the races, religions of ancient civilizations, what Stonehenge meant,” creates for her salvation a golem, as though all her cosmopolitan intelligence and sensibility were a secret source of guilt. In the same way, Miss Ozick bends her subtle, beautifully controlled prose and strange imagination to the service of folk magic. It is, in the end—despite the brilliance, despite the humor—an odd and uneasy displacement, like the Chagalls in Lincoln Center.

Advertisement

Eva Figes’s Waking is a life distilled into a series of brief monologues—the whole book runs to only eighty-eight pages—a kind of seven ages of woman. But the speaker is a woman who sleeps badly and finds relationships both difficult and unrewarding, so perhaps seven ages of loneliness is a more accurate description, loneliness from childhood to old age at, roughly speaking, ten-year intervals: first the five-year-old woken by cockcrow, impatient to be up and out in the garden; then the adolescent obsessed with her looks and the looks men give her, mooning over the fantasy knight on his fantasy charger who will rescue her from her drab and restrictive parents; then the young mother, heavily pregnant with a second child, exhausted by domesticity and her husband’s crass indifference.

Then there is the thirty-five-year-old divorcée in bed with a lover who has finally awakened her to pleasure, but worried that her children sleeping in the adjacent room will overhear their love-making; then middle-aged and alone again, brooding about a woman friend who is dying of cancer and about her own resentful son, still in the next room but now noisily bedded down with a girl; then really alone, her children gone off, married and out of touch, no love lost, the room dusty and untended, her light quenching, her world as gray as her hair; finally in a hospital, drifting in and out of consciousness until death comes as a glimmer of lost childhood—as a mother more tender and reassuring than her own mother in the opening chapter, taking her lost child home.

The monologues are written in poetic prose: no plot to speak of, all mood and sensibility, a style Beckett brings off time and again, perhaps because even his most murmuring, far-off voices have a cranky individuality and wit that keep the whole tricky performance healthily objective. Miss Figes, however, is not much interested in wit and there seems little distance between her and her narrator. Instead, the monologues form a kind of rhapsody of the self: the narrator describes herself and her changes in detail—eyes, hair, mouth, coloring, body—and no one else is even given a name. Her primary responses to the world are distaste and, at every stage except the last, resentment.

She is presented as a woman diminished by intimacy, for whom everyone is an intruder, apart from her fellow victim, the dying friend. Not even her lover is spared, despite the pleasure he brings her. The section ends with her faking an orgasm so he will go quickly before the children wake; then:

He murmurs words I want to hear, he kisses and touches lightly now, the curve of one breast, my throat. I raise one arm and look at it. He looks at it also and lifts his arm to meet it, palms touching, fingers interlaced. He brings his arm down to look at his wristwatch.

“I must go,” he says.

Her only relief from this even-handed, relentless narcissism is when the world out there suddenly shifts and seems beautiful: the early light slides across the floor, a curtain moves in the breeze, the birds start up their hesitant dawn chorus. Miss Figes is moved by the world without people and writes of it tenderly, delicately:

The night is my own. I walk barefoot to the window and draw back the curtains. I watch moonlight over the silent gardens, shadows sucked into the apple tree like ink into blotting paper. Nobody watches me, nobody hears.

She is also strong on her narrator’s manifold resentments: her sullen husband, the blind labor of motherhood, her own adolescent contempt for her parents’ flabby bodies, her adolescent son’s equal contempt for hers.

But there are moments—particularly in the opening monologues—when both her rhapsodies and her rage run on too slackly for a book so condensed and so apparently controlled. Kipling, who wrote some of the sharpest, cleanest prose in the language, said that when he finished a story he put it away for a few weeks, then went through it with a bottle of India ink, blotting out all the flourishes he had been most proud of when he was writing. If Miss Figes had been as ruthless with her adjectives and adverbs as her narrator is with her family, Waking would have been even shorter than it already is, but fiercer and more pure.

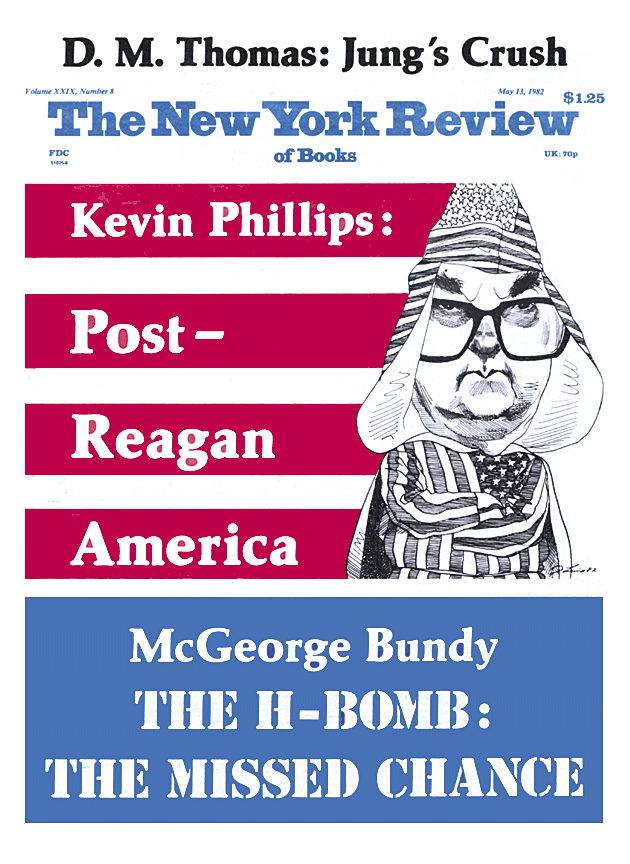

This Issue

May 13, 1982