Time and again politicians come a cropper over a minor episode which they have failed to foresee and which blows up into a crisis that escapes their control. Casas Viejas was an Andalusian pueblo of some two thousand inhabitants, a sizable number of whom embarked on an ill-conceived rising in 1933 against the government of the Spanish Republic. In re-establishing “order” a degenerate captain of the Assault Guards, a unit recently set up by the government, massacred twelve peasants and day laborers. The subsequent outcry discredited the prime minister, Manuel Azaña y Diáz, and with him the democratic republic of which he was the most able and eminent defender.

Jerome Mintz’s splendid book shows how it all happened. The rising of Casas Viejas was not, as we were all led to believe by Eric Hobsbawm, the work of “pre-political” primitive rebels stirred by messianic frenzy. The villagers had been organized loosely in the anarchosyndicalist union, the CNT, which consistently opposed the Republican government as compromised and reformist. Their rising was the response of a poverty-stricken, half-starving community to the call for a nationwide revolutionary strike issued by the fanatics of the Iberian Anarchist Federation, the FAI.

Professor Mintz first shows how the revolutionary purists of the FAI gained control within the CNT by tactics of terror and factional bullying first evolved by the Jacobins in the French Revolution, and how they flung the prestige of that great union into sponsoring a strike that was an exercise in revolutionary gymnastics and had no chance of success. “The uprising in Casas Viejas,” Jerome Mintz proves, “was a pathetic attempt to join an ill-fated national in surrection.”

On January 10, 1933, the local FAI leader sent a message to the faistas in Casas Viejas ordering them to carry out an insurrection. The CNT union in the village was run by moderates who knew that the anarcho-syndicalist national revolution had fizzled out; but, as one of them said, “I lack the words to convince the youth. We can’t hold them back.” Casas Viejas lurched into an isolated, doomed rebellion. On January 11 a small group besieged the Civil Guard barracks. Since poaching was a local occupation there were plenty of shotguns in the village. In the attempt to take the barracks two guards were shot dead. The pueblo was soon retaken by a force of Civil Guards. Most of the rebels fled to the hills, but two took refuge in the thatched cottage of “Seisdedos”—“Six Fingers”—an elderly charcoal burner of mild anarchist leanings. A Civil Guard went to the door of the cottage and was shot. It was then that Captain Rojas arrived with his Assault Guards, their nerves on edge. They burned the cottage, shooting like rabbits those who ran out from the flames. If that had been all, there would have been no fuss, no Casas Viejas affair. But Captain Rojas rounded up twelve men at random and shot them in cold blood.

This was the massacre of Casas Viejas on which the opposition pounced to crucify Azañna. Rojas, a brazen liar, to absolve himself claimed to be obeying orders from above. Azañna’s fault was that he did not take the trouble to find out in time what had happened and appeared, if not to have ordered the shootings, then at least to be covering up a massacre committed on the orders of his security chief and minister—orders for which he as head of the government was technically responsible. Azañna was sickened by the base accusations of the parliamentary opposition. He was reduced to black despair, brought down by the testimony of a sadistic soldier.

The reconstruction of this sad story by Professor Mintz is a brilliant and moving combination of conventional research and oral history. Oral history illuminates not only the events of January 1933 but the subsequent life histories of the obscure actors: the savage persecutions of the anarchists by the victors of the Civil War; the long years of starvation in prison—a particularly terrible experience in the 1940s; the years spent in wandering in the mountains to avoid capture. As for Captain Rojas, lying to the end, he was expelled from the army for requisitioning an army vehicle to give a tart a joy ride.

When Mintz has finished, little is left standing of Hobsbawm’s thesis; the observations in my own books on anarchist free love and vegetarianism are dismissed as the silly nonsense they are. Even the revered father of Andalusian agrarian social history, Diáz del Moral, takes a few hefty knocks for his bias in favor of landlords and the vague racialism that attributes the sudden “inexplicable” surges of peasant jacqueries—which can be explained by the national aspirations of a depressed and repressed class—to Moorish blood. So do some popular propaganda myths: for instance the elevation of the poor old man Six Fingers into the pantheon of anarchist heroes and martyrs, when his only contribution to the history of anarchism was an accident: two of his relatives involved in the shooting of the Civil Guards took refuge in his inflammable thatched hovel.

Advertisement

Nor is this book a bare account of a pathetic village insurrection. The early chapters trace with sympathy and admirable clarity the history of anarchosyndicalism and its implantation in Casas Viejas. The anarchist ideal as it was formulated in Spain was incompatible with democratic reformism; the repeated and futile anarchist insurrections did much to destroy its credibility in a Spain where democracy was a fragile growth. That the gestation of reform—particularly agrarian reform, which might have given the poor of Cases Viejas something to thank democracy for—was painfully slow in the Second Republic no one can deny. But anarchists rejected reformism, as such, as a tepid form of social engineering that merely served to provide a respectable cloak to an exploitative and incurably corrupt society.

Yet anarchism has its own peculiar brand of moral corruption. The revolutionary elitism of the FAI regarded the workers as cannon fodder in a revolution that one day would succeed, but that even if it failed at the time in a botched insurrection—and the FAI insurrections were hopelessly botched affairs—would serve to tense the revolutionary muscles of the proletariat and provide an inspiring catalogue of martyrs, the memory of whose blood would fructify the revolutionary subsoil. No doubt the faistas were ready to sacrifice their own lives; but it is an unattractive philosophy that argues that because you are willing to sacrifice your own life in a hopeless venture then others are obliged to sacrifice theirs. Admirers of the faista heroes Buenaventura Durruti and the Ascaso brothers should contemplate Mintz’s account of dogs licking up the blood of deluded peasants in the streets of Casas Viejas. Alas, these slaughtered saints have not been avenged; their sacrifices have not given birth to an anarchist society. But Jerome Mintz’s book ensures that they will be remembered with charity.

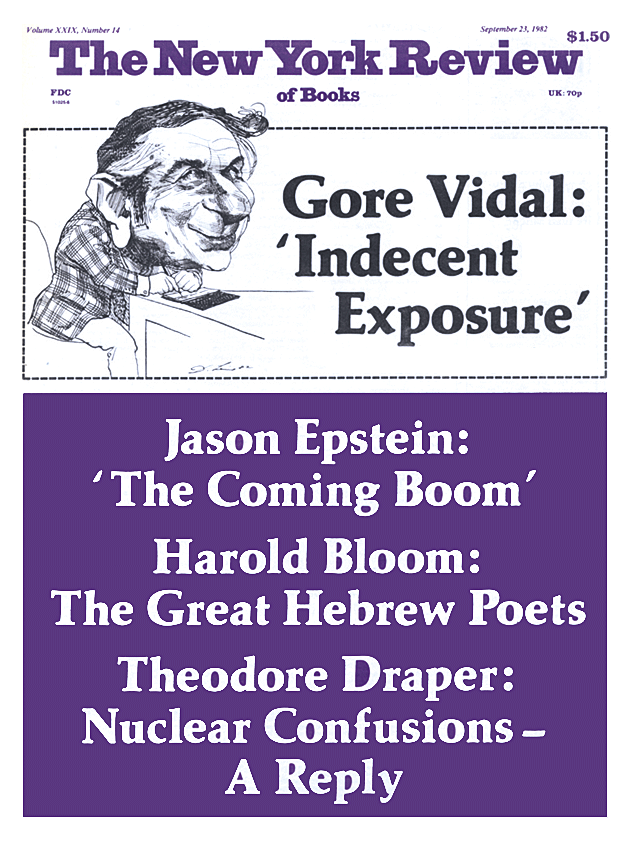

This Issue

September 23, 1982