Like the Russian Revolution, the Cuban events of 1959-1960 coincided with a literary revival, intense but short-lived. This rapid flowering was chiefly visible in the Monday supplement of the newspaper Revolución, and among the founding editors of this supplement, called Lunes, was the poet Heberto Padilla, newly returned, like many other radical intellectuals, from ten years of exile in the United States. It was characteristic of this group that, in contrast to the Orígenes circle of their seniors who, being nonpolitical, had remained at home during the Batista regime, they tended to write social poetry, variously influenced by the poets of the countries that had given them refuge. The poetry of the Lunes group is direct and economical, and happily free from the prevailing Hispano-American rhetoric.

The group was short-lived. In fact, except for Padilla, only one continues to write poetry, Pablo Armando Fernández, who publishes infrequently, his last book having appeared in Spain in 1969. Of the rest, Roberto Fernández Retamar is an important editor, and writes mostly criticism, and the highly talented José Álvarez Baragaño died suddenly in 1962, with his powers still only partially developed. He served rather as a link with the Orígenes group than as a practitioner of the new Lunes directness.

Now, twenty years later, Heberto Padilla is almost the sole survivor of these pioneers. Silence or conformism has overtaken the founders of Lunes, which has become a term of opprobrium in Cuba. “So much money was wasted on that publication,” we are told. And now Padilla, after brief domestic fame and a long eclipse, has published an ample selection of his poetry in New York, where he has at last been allowed to return.

Padilla’s first volume—if we omit a small collection he published at the age of sixteen—reveals in its title El justo tiempo humano (The Right Moment for Humanity) the poet’s optimism in 1962. It is scantily represented in this selection. The poetry is spare but romantic. For Padilla’s predominant influences have been Blake, Wordsworth, and Byron, and those Russian poets who were strongly influenced by English romanticism. The outstanding sequence of this first Padilla volume is “The Childhood of William Blake,” a series of ten reflections on incidents in Blake’s life and on his art, projected forward from imagined forebodings in his childhood. From these brief poems Blake emerges as a poet and engraver, as a wanderer in the London streets, and as the prophet not only of industrialism and its horrors, but also of the new Jerusalem. I should like to quote this poem in the original, since it displays Padilla’s splendid and gnomic economy, a quality rare in Hispano-American poetry, in a way that does not survive translation. However I will be content to give the second section in the present translation.

We are in the Lambeth house that the child William Blake will inhabit as a man, a place that Padilla visited more than once during a stay in London:

Wear his fear, that wheels like your carefree wing,

Bird of whispers! Bird of grief!

It is night now. No one calls.But through the closed window

he hears the seedpods crack on that tree

and it sounds like someone knock-

ing.

His most secret game is charged with cunning.

Depressed, he sees on the black expanse

the smoke of houses burning in the night

and the passing of beasts backlit by the fire.Don’t open the door. Don’t call.

Here Padilla voices his fear that terror will eventually overcome the new Jerusalem that seemed to be coming to birth in Cuba. This sequence is a social poem, but one of great depth and perspicacity. El justo tiempo humano, however, contains many buoyant poems whose exclusion from Legacies I regret.

Padilla’s next volume, Fuera del juego (Sent Off the Field), which was completed by 1968, proclaimed his fear much more loudly. It contained several poems of the quality of the William Blake series, among them a group written in Russia, where he had worked as a foreign correspondent, and others critical of regimented societies, though none that referred directly to Cuba. Indeed several of them celebrate the poet’s delight in love and nature, in language that recalls the early Pasternak of My Sister, Life. The final verse of “The Last Spring in Moscow” might be a translation from Pasternak:

Houses take fire in this new air.

The ballast of winter is dumped in the rivers.

Life is the sprout that opens slowly

as a wound closes.

The birch tree brings out its blind leaf.

Even the secret substance

in cocoons begins to vibrate,

echoed in each ageless walker.

And love is the only element.

With the sudden spring, desires awake

like aurochs, thirsty and full of silence.

But there are also poems in which another side of Russia is hinted at, if not directly expressed. The lyrical “Song of the Spasskaya Tower” may seem to refer only to the victims of the czars, who perished in that prison. Nevertheless the guard on the tower acknowledges in the last lines

Advertisement

that there is no terror

that wind can hide.

No terror, neither ancient nor contemporary.

The book Fuera del juego was closely analyzed for the Cuban authorities by a pseudonymous “detector of heresies,” who shredded every poem for possible counterrevolutionary meanings. His criticism was published in Verde olivo, the organ of the Cuban army, and this marked an early stage in the process toward the disaster that was foretold in the image of the seedpods cracking on the tree. The poet was imprisoned, humiliated, silenced, in the tenth year of the new “age of justice” that he had welcomed.

Here I must declare my own involvement in “the Padilla case.” In 1968 I was invited for the second time to be a member of a jury to award a poetry prize. I already knew Padilla and admired his poetry, so when the competing typescripts were read to me—I have poor vision—I had no difficulty in recognizing in the pseudonymous poems the style of Heberto Padilla. Nor was it difficult to decide that this was by far the best entry. None of my fellow jurors had any doubt about that; and despite some ugly pressure, perhaps to persuade us to declare the competition without a winner, we unanimously awarded the prize to the author of Fuera del juego.

The prize consisted not only of the book’s publication and a sum of money, but of a free trip abroad. I knew that Padilla had been deprived of his official job, and had been refused an exit permit to take a lectureship in France. He hoped by winning the prize to be able to leave the country. The book was eventually published in a small edition with an introduction by a Party hack who pointed out its deeply antirevolutionary content. The free trip was not allowed, and when my wife and I said goodbye to Padilla, we were not to meet again until last year in New York.

After we left Havana, “the Padilla case” gathered momentum. Abuse in the press was followed by the poet’s arrest and imprisonment, and by his forced admission of his “ideological errors” before a conscripted session of the Writers Union. There followed ten years of silence during which Padilla was employed as a translator, away from Havana, and kept permanently out of touch with his foreign friends. This was greeted by the protests of those European intellectuals (myself among them) who had heretofore believed that Castro’s revolution had brought a measure of cultural freedom to Cuba.

The poem “En tiempos difíciles” (In Trying Times) is perhaps the key to Padilla’s growing resentment in his prize-winning volume against though suppression, and compulsory conformism of all kinds:

…a dream

(the great dream);

they asked him for his legs

hard and knotted

(his wandering legs),

because in trying times

is there anything better than a pair of legs

for building or digging ditches?

They asked him for the grove that fed him as a child,

with its obedient tree.

They asked him for his breast, heart, his shoulders.

They told him

that that was absolutely necessary.

They explained to him later

that all this gift would be useless

unless he turned his tongue over to them,

because in trying times

nothing is so useful in checking hatred or lies.

And finally they begged him,

please, to go take a walk.

Because in trying times

that is, without a doubt, the deci- sive test.

The prevailing mood of Fuera del juego is one of anger and disillusion reinforced by the romantic feeling that in the new society there is no place for the poet. He is rejected, indeed “sent off the field.” But still Padilla was not attacking the revolution itself. There was good reason, however, for the bureaucrats’ objections to the book, more than I saw at the time as a liberal used to judging poetry by poetic standards. Most of the poems in Fuera del juego are brilliant with a barbed economy and originality of phrase, of which the brief “Alchemists” will serve as an example:

When magic was in bankruptcy,

in those days when the crows

seemed to have given up the work

(and the philosopher’s stone held no more augury),

they took an idea,

a furious formulation of life,

and they made it spin

like the astrologer’s globe;

thousands of brazen hands

making it spin

like a whore returned to rape men,

but, as for that idea,

only its enemies remain.

Between the controversy over the prize and his arrest Padilla continued to write satirical poems, which he sent to his friends abroad. In their wit and conciseness they recall some of Blake’s attacks on his favorite enemies. He was also learning from Byron how much could be delivered by a single quatrain:

Advertisement

ACCORDING TO THE OLD BARDS

Don’t you forget it, poet.

In whatever place or time

you make, or suffer, History,

some dangerous poem is always stalking you.

One is reminded of Mandelstam’s lampoon on Stalin, which led to his death years later in a concentration camp.

After Padilla’s release and “confession,” only a few poems were sent abroad, and these few were published in this journal. But a number written in the ten years before he was allowed to emigrate are printed without dates in Legacies and interspersed with poems from his two published books. This disorder is unscholarly and deplorable. The reviewer can, however, attempt to divide them according to theme, and so isolate Padilla’s preoccupations during his years of silence.

There are first those pieces, like the title poem “Legacies,” devoted to the theme of childhood and ancestry. In these Padilla seems to demolish the time sequence and see himself as the contemporary of his grandparents who first landed in Cuba. His second and related concern is also with history, particularly with those characters in the past with whom he can identify himself in his present situation. There is Pico della Mirandola, master of all knowledge who yet did not foresee his own fate; and the Spanish poet Quevedo, who identifies himself with all poets of every age since Homer, and Sir Walter Raleigh, imprisoned in the Tower of London and isolated by his own thoughts from an outward beauty that he can now no longer recall. These poems, while somewhat reminiscent of Auden’s on Edward Lear and Rimbaud, are, however, less objective and detached. Each of Padilla’s models reflects some aspect of himself. Let us take the poem devoted to the fifteenth-century humanist Pico della Mirandola:

When he used words, not as he first did

for the pure pleasure of making the air tangible,

but to rid everything

of the ruin of corruption,

so that when he used the word

Iflower

he immediately destroyed the woes

of every age.

When he used the word coitus, he threw out

all sense of commerce—very well established—

and drove the Treasury (those whores)

to the point of bankruptcy.

Was this Pico’s ambition or Padilla’s?

Third, there is a group of poems addressed to his wife Belkis, herself a fine poet, which turn on the theme of passion, and of the impossibility of shutting out the world in mutual delight. These poems evince not only joy in marriage but an enhanced pain at the omnipresence of a hostile and unpitying world. And last, there is the remarkable poem to his friend and fellow poet Pablo Armando Fernández, now silent though tolerated by the Cuban regime. This is the one poem in the book that reaches out toward the metaphysical, a quality so far absent from Padilla’s poetry. For he entrusts to Pablo Armando, a theosophist “who can argue with death on its own terms,” the duty of interpreting and defending him after his death—a condition that he, Heberto Padilla, cannot now understand:

for there is no magic that is denied to your hand

and all our tongues learned from yours.

If after my death anyone should want it,

only you could unlock me for them,

key by key.

This poem, more than all the rest, points to new directions open to Padilla in the future.

It is difficult for me to assess this volume, since I have known most of the poems in it for many years, and have myself made translations of a considerable number of them. These were published in London in 1972 by André Deutsch as Sent Off the Field. In the first place, as I have already said, the poems are printed in a regrettable disorder. There is nothing to tell the reader, for instance, that “The Childhood of William Blake” was written many years before the poem addressed to Pablo Armando Fernández, his friend and fellow poet. Further, some very good poems from Padilla’s first volume which voice his initial enthusiasm for the revolution are unaccountably omitted. I do not think, from my knowledge of the poet, that he has any Audenesque wish to edit his past. Yet El justo tiempo humano is here reduced to two or three poems.

On the subject of the translations I am in even greater difficulty. These are, in many cases, too literal to be poetic. Though Padilla’s statements may appear at first sight straightforward, they are often in fact highly ambiguous, in the manner of the Spanish seventeenth century. In many of the poems when Padilla refers to his ancestors, with whom he often feels himself to be a contemporary, he is referring not merely to his grandfathers who came to Cuba from Spain, but to those Spanish poets to whom he feels akin. Indeed, one of the best poems of the present collection is dedicated to that master of black irony, Francisco Gómez de Quevedo, who saw the walls of his country falling apart.

Indeed the problems that Padilla sets for his translator, though not always obvious on a first reading of the Spanish, are considerable. He is not a simple poet. Let me quote as evidence the opening sections of “The Last Thoughts of Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower of London.” The relevance of the poem to Padilla’s own situation is obvious. First the Spanish:

Hasta ayer se movía

Vibraba al centro de la vida,

como la sangre agotaba los límites de su cuerpo

Cada paso restauraba otro paso

Cada hazaña otra hazaña

Cada palabra hacía trizas la anterior

Árbol o luz o calle o mar o cielo

afirmaban la intemperie donde se diluía

pero hasta ayer

a ciegas sin saberlo.

Ahora se agrietan para él las dimensiones

El pecho se le comba en la cabeza

Los ojos en los pies como una idea fija

Y el mundo es bello más allá de esta torre

más allá de los sótanos

de las celdas

de estas cámaras de torturas

El mundo más hermoso que una puerta de escape

Los aires libres como el aire libre

Los mendigos y reyes ayunando a la fuerza

bajo los puentes

entorchados como porteros

ciñéndose los harapos multicolores

fornicando con bestias o mastur- bándose

pero en la libertad.Till yesterday he could move,

alert, full of life.

Like blood, he used his body to the limit.

Each step he took led to another step,

each scheme to another scheme.

Each word replaced the previous word—

tree, light, street, sky—

they all confirmed a crumbling world in which he foundered

until yesterday,

blind without knowing it.

Now, for him, all sense of scale disappears.

His head drops on his chest.

His eyes are fixed on his feet.

Beyond the tower all is wondrous,

outside the dungeons,

outside the cells,

the torture chambers,

the world is even more wondrous than the idea of escaping,

open-air places than the open air,

beggars and kings inevitably fast- ing,

under bridges,

dressed up like doormen,

sporting multicolored rags,

fornicating with beasts, or mastur- bating—

but free, all of them free.

At the beginning the translator departs from the Spanish to make Raleigh “alert, full of life.” But the meaning is, I think, that yesterday he was in the middle of life, his blood pulsing so exuberantly as to burst life’s bounds. Again the word “foundered” misrepresents the poet’s intention. Until yesterday Raleigh was at one with—literally “diluted in”—that world, from which he has now been precipitated. I could continue to cavil at this translation, especially at “puerta de escape,” which is not the idea but the way of escape and “a la fuerza,” which suggests that the fasting was imposed forcibly. But all that I wish to show is that Padilla’s poetry is deceptively simple at first sight, far more complex on a second reading. Those who follow the Spanish on the left-hand page of Legacies will appreciate layers of meaning that do not emerge on the right. They will conclude, I think, that Padilla is one of the most important poets of the last quarter of a century.

He is a poet who has lived through that dawn in which for a while it was exciting to be alive, but who, in rejecting inflated hopes, has not sunk into disillusion and bitterness or crabbed conservatism, but continues to accept and interpret new experiences. Moreover, having spent his formative years in the United States and some time also in London and Moscow, he unites elements of the English and Russian traditions. Indeed he spent some of his years of isolation in Cuba translating the English romantic poets, especially Blake. Thus he is that rare creature, an international poet, capable of making his native Spanish move to new rhythms.

Perhaps the strongest expression of Padilla’s persistent drive as a poet, his peremptory rejection of partial successes of cheaply won fame, of halfway solutions, is to be found in the poem “Overboard”—presumably a late piece—of which I quote the conclusion:

Over the side

with the clown suit that made no one laugh

the black corsair’s costume

the ads of the snake-oil peddler

cures for the mange of the whiners

Over the side with undeserved winnings

with goods stolen in the flimflam of the raffle

Over the side with all good reputations

(which are really bad ones)

and dice and cards

that threw them-

selves at my feet

when they should have

died in my arms

Over the side with raddled sleep

with gall

with the ways of jugglers, knife throwers, quacksalvers

but not with hope

nor the passion for life

the things that keep us

going on, going onPor la borda

el traje de bufón que a nadie hizo reir

la vestimenta de corsario negro

los letreros de mercader de ungüentos

para la sarna de los tristones

Por la borda lo que gané sin merecer

Too many contemporary poets are content with their chance winnings. With whom may Padilla be compared? I think of the best of Voznesensky, of the Lowell of Life Studies, and the poems of Seamus Heaney.

“This man,” the poet and communist editor Roberto Fernández Retamar said to me during the controversy over the prize, “wants to be our Pasternak.” This was said in malice, and showed a narrow view of Pasternak. But whether Padilla intended to take such a part or not, it belongs to the past. The later poems of Legacies show him to be moving into a phase in which defensive action is over. Padilla is now reasserting the claim Blake made for poetry as a prophetic art.

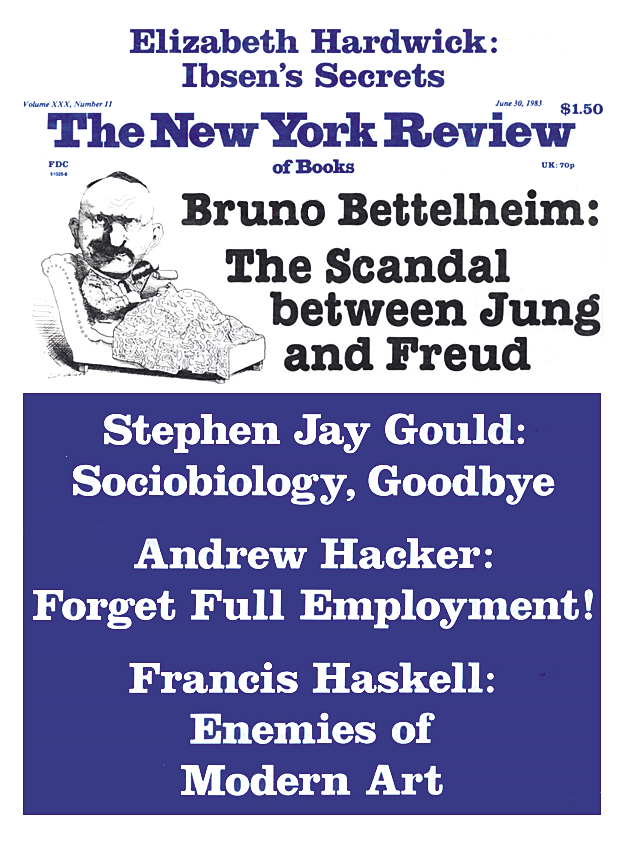

This Issue

June 30, 1983