We must have our man in Havana, you know. Submarines need fuel. Dictators drift together. Big ones draw in the little ones.

—Graham Greene

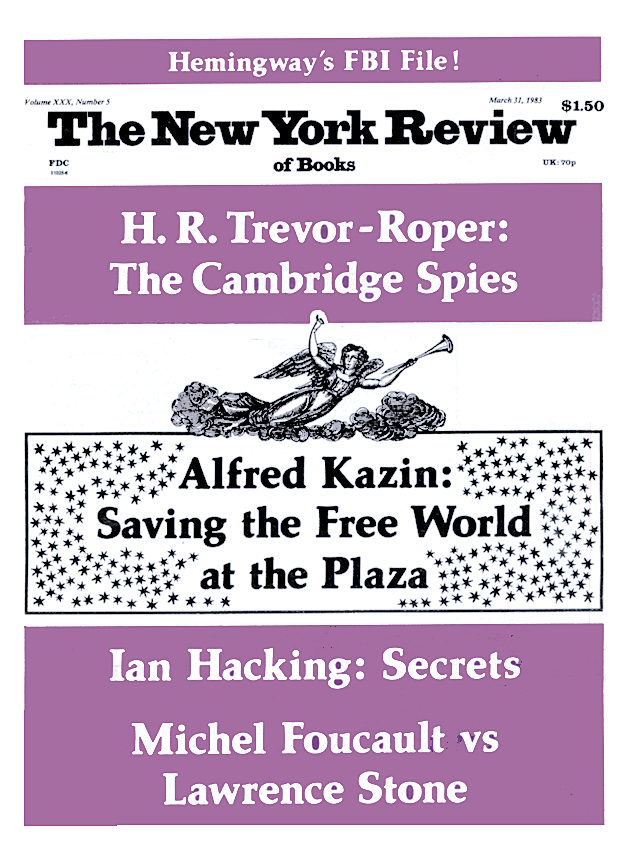

The FBI file on Ernest Hemingway reveals that Hemingway organized a private spy network in Cuba during World War II; that the Bureau made unsuccessful attempts to control, mock, and vilify him; that it feared his personal prestige and political power; and that, in a pathetic episode, it tracked him to the Mayo Clinic, just before he died. The file contains 124 pages—fifteen withheld “in the interest of the national defense,” fourteen blacked out except for the salutation, a few almost illegible because of the faded original typescript. It runs from October 8, 1942, to January 25, 1974 (thirteen years after his death), and much of it has to do with the first year of Hemingway’s wartime activities in Cuba. The file is extremely repetitive, and becomes unintentionally funny, particularly when the solemn bureaucrats report the bizarre behavior of the writer.

The characters in this tragicomedy include Hemingway’s friends Spruille Braden (1894-1978), the American ambassador to Cuba; Robert Joyce, the second secretary, coordinator of intelligence activities and liaison with the FBI agents; and Gustavo Durán (1907-1969), who skillfully commanded Loyalist divisions in the battles of Boadilla, Brunete, and Valencia during the Spanish Civil War. The villains are Raymond Leddy, the legal attaché (i.e., FBI agent) in Havana, who helped train men for the Cuban FBI; and General Manuel Benitez, chief of the Cuban police and extortionist on a grand scale, who had previously played Latin lovers in grade-B Hollywood films.

Braden was born in Elkhorn, Montana (Hemingway hunting country), graduated from Yale, married a Chilean, had a successful career as a mining engineer and entrepreneur in South America. He was ambassador to Colombia before assuming the post in Cuba in the spring of 1942. Though often pompous and self-righteous, he was an independent and effective diplomat; strongly anti-communist, he was praised by the historian Hugh Thomas as “an intelligent man, with considerable Latin American experience…a distinctly Radical diplomat, with strong views of social reform. He was regarded by many Cubans as the best ambassador the US ever sent to Havana.”1

In his memoirs, Diplomats and Demagogues, Braden states that there were 300,000 Spaniards in wartime Cuba, of whom 15,000 to 30,000 were “violent Falangists.” Braden claims that he asked Hemingway “to organize an intelligence service that will do a job for a few months until I can get the [additional] FBI men down. These Spaniards have got to be watched.” Beginning in August 1942, Hemingway, according to Braden, “built up an excellent organization and did an A-One job.”2 His work ended with the arrival of the FBI operatives in April 1943.

Both Hemingway and the FBI state, more accurately, that Hemingway first approached Braden and volunteered to investigate the Spanish Falange with the aid of his Loyalist refugee friends. Supported by the ambassador, Hemingway discreetly established an amateur but extensive information service with his own confidential agents. He had twenty-six informants, six of them working fulltime, and twenty of them undercover men. His expenses came to a thousand dollars a month and he had 122 gallons of scarce gasoline charged to him from the embassy’s private allotment in April 1943.

Hemingway’s greatest administrative coup was to recruit Durán to assist him in what he called his Crook Factory. He informed Braden that the highly cultivated Durán, the son of a Spanish general, came from a fine family, was an excellent musician and composer of ballet scores, and had been the music critic of important Paris newspapers. When the Loyalist cause collapsed in 1939, Durán escaped to Barcelona, was rescued by a British destroyer and taken to London. He married an American, moved to the United States in 1940, and worked for Nelson Rockefeller, who was coordinator of inter-American affairs for the State Department. According to Agent Leddy, in a letter written to J. Edgar Hoover on August 13, 1943, Hemingway described Durán to Braden “as the ideal man to conduct this work, ‘an intelligence and military genius that comes along once in a hundred years.”‘ In For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), Robert Jordan thinks of Durán to fortify himself before an attack: “Just remember Durán, who never had any military training and who was a composer and lad about town before the movement and is now a damned good general commanding a brigade. It was all as simple and easy to learn and understand to Durán as chess to a child chess prodigy.” 3

In October 1942 Durán was sent from Washington for the special purpose of assisting Hemingway. Two months later, according to D.M. Ladd, a senior FBI official, the general was getting out of hand and had already become a potential enemy of the FBI: “Durán’s operations and attitude…assume proportions of domination and direction rather than assistance to the agencies properly engaged in investigating subversive activities.” By August 1943 Leddy, unaware of the labyrinthine politics of the Spanish left, was zealously conducting an investigation to determine whether Durán was an active member of the Communist Party and political infiltrator into the American embassy. (Durán, investigated and cleared by the State Department in 1946, had a distinguished career with the United Nations in Chile, the Congo, and Greece between 1946 and 1969.)4

Advertisement

Braden, a fierce crusader against corruption in Cuba, also directed Hemingway to look into the involvement of Cuban officials in the pervasive local graft. Ladd, who called Braden “a very impulsive individual,” warned Hoover on December 17, 1942, that this would be dangerous. If we get involved in investigating Cuban corruption, he said, “it is going to mean that all of us will be thrown out of Cuba ‘bag and baggage….’ [Hemingway, like Durán,] is actually branching out into an investigative organization of his own which is not subject to any control whatsoever…. Hemingway’s activities…are undoubtedly going to be very embarrassing unless something is done to put a stop to them.” The FBI attempted to thwart Hemingway in two ways: by discrediting the information that was supplied to Braden and passed on to Leddy; and by claiming that Hemingway, like Durán, was a communist.

A week before the visit of President Batista to Washington in 1943, Hemingway warned that General Benitez was proposing to seize power when Batista was out of the country. Leddy looked into the matter and pointed out that no such preparations were observed by FBI agents working “in daily contact” with those at police headquarters. But Braden reported in June 1944 that General Benitez, a habitual plotter, “was meeting in a house in the outskirts of Havana, making plans to throw out Batista.”5

On December 9, 1942, Hemingway reported sighting a contact between a German submarine and a Spanish steamer, Marqués de Comillas, off the Cuban coast while he “was ostensibly fishing with [his millionaire friend] Winston Guest and four Spaniards as crew members, but actually was on a confidential mission for the Naval Attaché.” The FBI duly investigated the incident and reported “negative results.”

According to a Bureau memo from C.H. Carson to Ladd on June 13, 1943, Hemingway, after reading about a new type of oxygen-powered German submarine, investigated “the supply and distribution of oxygen and oxygen tanks in Cuba.” Hemingway enthusiastically claimed (in the FBI’s translation of his words): “At last with this development we have come to the point after months of work where we are about to crack the submarine refuelling problem.” The FBI checked the supply and distribution of the island’s oxygen and found everything properly accounted for. They gleefully announced, “Nothing further was heard from Hemingway about the subject,” and noted the change in his attitude: “Hemingway’s investigations began to show a marked hostility to the Cuban Police and in a lesser degree to the FBI.”

Another ludicrous confrontation between the dogged Leddy and the exasperated Hemingway sounds like a scene out of Graham Greene:

In January, 1943, Mr. Joyce of the Embassy asked the assistance of the Legal Attaché in ascertaining the contents of a tightly wrapped box left by a suspect at the Bar Basque under conditions suggesting that the box contained espionage information. The box had been recovered from the Bar Basque by an operative of Hemingway. The Legal Attaché made private arrangements for opening the box and returned the contents to Hemingway through Mr. Joyce. The box contained only a cheap edition of the “Life of St. Teresa.” Hemingway was present and appeared irritated that nothing more was produced and later told an Assistant Legal Attaché that he was sure that we had withdrawn the vital material and had shown him something worthless. When this statement was challenged by the Assistant Legal Attaché, Hemingway jocularly said he was only joking but that he thought something was funny about the whole business of the box.

After this incident the Bureau was forced to conclude: “The ‘intelligence coverage’ of Hemingway consisted of vague and unfounded reports of a sensational character…. [His] data…were almost without fail valueless.” Though both Braden and the State Department praised the quality of Hemingway’s reports, it seems clear that this information, however well intentioned, was (like that of Graham Greene’s agent Wormold) based more on fantasy than on fact. The entire Crook Factory, which Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, refused to take seriously, was most probably a charitable scheme to support a few dozen indigent Loyalists. Leddy noted, with considerable relief, that Hemingway’s organization was disbanded as of April 1, 1943, because of a “general dissatisfaction over the reports submitted.”

On October 8, 1942, Leddy had told Hoover that Braden “has acceded to HEMINGWAY’s request for authorization to patrol certain areas where submarine activity has been reported…and an allotment of gasoline is now being obtained for his use.” But Hemingway’s subhunting expeditions, which replaced his spy network, were little more than an excuse for fishing and drinking with friends on his boat, the Pilar. Only the force of Hemingway’s legend and overpowering personality could have convinced the ambassador, despite overwhelming evidence from the FBI, that his spy games had any value.

Advertisement

Leddy was both disdainful of Hemingway’s activities and fearful of his power. Trained to see everything in black or white, without any subtle gradations of meaning, he was puzzled by the communist attacks on Hemingway, who had supported the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War. The novelist clearly troubled the FBI just as the Bureau would later worry him; and Leddy wrote directly to Hoover about his difficulties with Hemingway. Like everyone else the FBI disliked, Hemingway was immediately suspected—and privately accused—of being a communist, though no evidence was—or ever could be—offered to prove this. The mood, tone, phrases, and techniques of the FBI during the hot war in the early 1940s clearly foreshadow those employed by Senator McCarthy during the cold war in the early 1950s.

Leddy’s first letter to Hoover, which opens the file on October 8, 1942, makes two charges against Hemingway. First, “when the Bureau was attacked early in 1940 as a result of the arrests in Detroit of certain individuals charged with Neutrality Act violations for fostering enlistments in the Spanish Republican forces, Mr. HEMINGWAY was among the signers of a declaration which severely criticized the Bureau.”6 (Ladd called this the “general smear campaign.”) Second, “in attendance at a Jai Alai match with HEMINGWAY, the writer [Leddy] was introduced by him to a friend as a member of the Gestapo. On that occasion, I told HEMINGWAY that I did not appreciate the introduction.”

Hoover dug into his files and answered in person on December 17 to enlighten and encourage his local agent: “Any information which you may have relating to the unreliability of Ernest Hemingway as an informant may be discreetly brought to the attention of Ambassador Braden. In this respect it will be recalled that recently Hemingway gave information concerning the refueling of submarines in Caribbean waters which has proved unreliable.” Two days later Hoover added: “[Hemingway’s] judgment is not of the best, and if his sobriety is the same as it was some years ago, that is certainly questionable.”

On the same day that Hoover first wrote to Leddy, Ladd told Hoover that “Hemingway has been accused of being of Communist sympathy, although we are advised that he has denied and does vigorously deny any Communist affiliation.” This was followed on April 27, 1943, by nine typed pages of Hemingway’s “Activities on Behalf of Loyalist Spain,” which made his humanitarian efforts to provide ambulances for the wounded, medical aid for the sick, and asylum for the refugees seem like unconscionable acts. In the same report, under “Possible Connections with Communist Party,” the Bureau, without any supporting evidence, accusingly states: “In the fall of 1940 Hemingway’s name was included in a group of names of individuals who were said to be engaged in Communist activities.”

Other FBI letters noted Hemingway’s first and only political speech at the American Writers Congress at Carnegie Hall on June 4, 1937, attended by such suspicious characters as Archibald MacLeish, Senator Gerald Nye, and Congressman John Barnard; Hemingway’s threat to expose “fascist influences” in the State Department and the Vatican, which he claimed were responsible for the political “castration” of the 1943 film version of For Whom the Bell Tolls; and Hemingway’s statement in Look magazine that there was “nothing wrong with Senator Joseph McCarthy (Republican) of Wisconsin which a .577 solid would not cure.”7

This was the FBI’s own internal “smear campaign”—but the Bureau did not dare to carry it out in public. The “communist” Hemingway, Leddy reported to Hoover, was himself attacked by communist newspapers in New York and Havana. In June 1943, Hoy (Today) quoted Hemingway as advocating “the sterilization of all Germans as a means of preserving peace” and claimed that For Whom the Bell Tolls was “directed against the Communist party and against the Spanish people.”8

Moreover, as Carson explained to Ladd in an FBI memo of June 13, 1943, Hemingway’s close friendship with Braden, his immense popularity in Cuba (where he was greeted like a popular monarch as he drove through the streets), his fame in America, and his prestige abroad made it imperative to keep a safe distance from the rogue elephant. If molested, he was capable of inflicting serious wounds on the Bureau:

Regarding Hemingway’s position in Cuba, the Legal Attaché advises that his prestige and following are very great. He enjoys the complete personal confidence of the American Ambassador and the Legal Attaché has witnessed conferences where the Ambassador observed Hemingway’s opinions as gospel and followed enthusiastically Hemingway’s warning of the probable [i.e., unlikely] seizure of Cuba by a force of 30,000 Germans transported to the island in 1,000 submarines. A clique of celebrity-minded hero worshippers surround Hemingway wherever he goes, numbering such persons as Winston Guest, Lieutenant Tommy Shevlin (wealthy son of a famous Yale football player), Mrs. Kathleen Vanderbilt Arostegui and several Embassy officials. To them, Hemingway is a man of genius whose fame will be remembered with Tolstoy….

It is known that Hemingway and his assistant, Gustavo Durán, have a low esteem for the work of the FBI which they consider to be methodical, unimaginative and performed by persons of comparative youth without experience in foreign countries and knowledge of international intrigue and politics.9 Both Hemingway and Durán, it is also known, have personal hostility to the FBI on an ideological basis, especially Hemingway, as he considers the FBI anti-Liberal, pro-Fascist and dangerous as developing into an American Gestapo.

On December 19, 1942, Hoover had already cautiously commented on the “impulsive” Braden: “The Ambassador is somewhat hot-headed and I haven’t the slightest doubt that he would immediately tell Hemingway of the objections being raised by the FBI. Hemingway [“one of the real danger spots in Cuba”] has no particular love for the FBI and would no doubt embark upon a campaign of vilification.”

Finally, the FBI realized that Hemingway, through his wife, Martha Gellhorn (a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt), had some influence with the president. Hemingway and Gellhorn had shown his pro-Loyalist film The Spanish Earth to the Roosevelts at the White House in July 1937. And on October 9, 1942, Leddy told Hoover with apparent awe: “During the week commencing October 12, 1942, Mrs. HEMINGWAY is to be the personal guest of Mrs. ROOSEVELT during her stay in Washington.” Braden took advantage of this visit to ask Martha to brief Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins about urgently needed funds to combat “the periodically reappearing enemy agents” in Cuba.10 In view of all this, Carson concluded, it was best to prevent a direct confrontation with their formidable adversary: “The Legal Attaché at Havana expresses his belief that Hemingway is fundamentally hostile to the FBI and might readily endeavor at any time to cause trouble for us…. It is the recommendation of the Legal Attaché at Havana that great discretion be exercised in avoiding an incident with Ernest Hemingway”—one of the few people, it appears, who could successfully resist the hostility of the FBI.

Though Hemingway won the first round with the FBI and concentrated on submarine-hunting when the Crook Factory was dismantled after eight months, the FBI kept watch on him for the rest of his life. Reports continued to be placed in his file on his connections with General Benitez (1944) and Gustavo Durán (1947), his political activities and intelligence work (1949), his crack about Senator McCarthy in Look (1955), and even the quarrel of his fourth wife, Mary, with a Havana gossip columnist about whether or not lion steak was, as she claimed, a delectable dish (1954).

Matters became more serious at the end of Hemingway’s life when his nostalgic support for the Spanish left and distaste for the cruelty of Batista’s regime (the police chief had still not overthrown the general) led to his naive and perhaps self-protective public support for the Castro government, which took power in January 1959 while Hemingway was away in Idaho and Spain. When he flew into Rancho Boyeros airport on November 3, 1959, as J.L. Topping of the embassy reported to the State Department, Hemingway told reporters:

- …He supported [the castro government] and all its acts completely, and thought it was the best thing that had ever happened to Cuba.

- He had not believed any of the information published abroad against Cuba. He sympathized with the Cuban Government, and all our difficulties.

- Hemingway emphasized the our, and was asked about it. He said that he hoped Cubans would regard him not as a Yanqui (his word), but as another Cuban. With that, he kissed a Cuban flag….

These rash statements horrified his closest Cuban friends—Mayito Menocal, Thorwald Sánchez, and Elicín Arguelles—soon to be dispossessed and driven into exile by Castro, and forced them to break off all relations with Hemingway. (Shortly after his death in July 1961 his house, boat, and other possessions were expropriated by Castro’s government.)

The drama closes on a sad note. A letter from the special agent in Minneapolis to Hoover on January 13, 1961, reports that Hemingway had secretly entered the Mayo Clinic: “He is seriously ill, both physically and mentally, and at one time doctors were considering giving him electro-shock therapy treatments.” (These treatments destroyed his memory and intensified his depression.) The psychiatrist treating him “stated that Mr. HEMINGWAY is now worried about his registering under an assumed name, and is concerned about an FBI investigation. [The doctor] stated that inasmuch as this worry was interfering with the treatments of Mr. HEMINGWAY, he desired authorization to tell HEMINGWAY that the FBI was not concerned with his registering under an assumed name. [The doctor] was advised that there was no objection.”

Both A.E. Hotchner and Mary Hemingway have written that Hemingway, at the end of his life, imagined that he was being followed and spied on by FBI agents in Idaho and in the Mayo Clinic, and that no kind of argument or evidence could change his mind or alleviate his irrational—but quite terrifying—fears.”11 The doctor’s ineffectual and absurd intervention could only have alarmed his patient. The FBI file proves that even paranoids have real enemies.

This Issue

March 31, 1983

-

1

Hugh Thomas, Cuba, or the Pursuit of Freedom, 1762-1969 (Harper and Row, 1971), p. 730. ↩

-

2

Spruille Braden, Diplomats and Demagogues (Arlington House, 1971), p. 283. ↩

-

3

Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls (Scribner, 1968), p. 335. ↩

-

4

See “Gustavo Durán of the UN Dies; Was Associate of Hemingway,” The New York Times, March 27, 1969, p. 47. ↩

-

5

Braden, Diplomats, p. 299. ↩

-

6

See “Arrest of 12 Accused of War Recruiting; FBI Agents Seize Men and a Woman Indicted for Acting for Spanish Loyalists; Prosecutor Says Detroiters Lured Prospective Soldiers at Communist Meetings,” The New York Times, February 7, 1940, p. 8. ↩

-

7

Ernest Hemingway, “The Christmas Gift,” Look, vol. 18 (May 4, 1954), reprinted in By-Line: Ernest Hemingway, edited by William White (Scribner, 1967), p. 417. ↩

-

8

See Ernest Hemingway’s ill-advised wartime assertion in his introduction to Men at War: The Best War Stories of All Time (Crown, 1942), p. xxiv: prevention of future wars with Germany “can probably only be done by sterilization.” For communist attacks on Hemingway, see Jeffrey Meyers, Hemingway: The Critical Heritage (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982), pp. 35-36. ↩

-

9

See Ernest Hemingway, Islands in the Stream (Scribner, 1970), p. 215: there were “the inescapable FBI men, pleasant and all trying to look so average, clean-cut-young-American that they stood out as clearly as though they had worn a bureau shoulder patch on their white linen or seersucker suits.” ↩

-

10

Braden, Diplomats, p. 289. ↩

-

11

A.E. Hotchner, Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir (Bantam, 1967), pp. 300-301, 308-309; Mary Hemingway, How It Was (Ballantine, 1976), p. 609. ↩