Because civilizations are finite, in the life of each of them there comes a moment when the center ceases to hold. What keeps them at such times from disintegration is not legions but language. Such was the case of Rome, and before that, of Hellenic Greece. The job of holding the center at such times is often done by the men from the provinces, from the outskirts. Contrary to popular belief, the outskirts are not where the world ends—they are precisely where it begins to unfurl. That affects language no less than the eye.

Derek Walcott was born on the island of Saint Lucia, in the parts where “the sun, tired of empire, declines.” As it does so, however, it heats up a far greater crucible of races and cultures than any other melting pot north of the equator. The realm this poet comes from is a genetic Babel; English, however, is its tongue. If at times Walcott writes in Creole patois, it’s not to flex his stylistic muscle or to enlarge his audience but as an act of homage to what he spoke as a child—before he spiraled up the tower.

The real biographies of poets are like those of birds, almost identical—their data are in the way they sound. A poet’s biography lies in his twists of language, in his meters, rhymes, and metaphors. Attesting to the miracle of existence, the body of his work is always in a sense a gospel whose lines convert their writer more radically than his public. With poets, the choice of words is invariably more telling than the story line; that’s why the best of them dread the thought of their biographies being written. If Walcott’s origins are to be learned, his poems themselves are the best guide. What one of his characters tells about himself may well pass for the author’s self-portrait:

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation….

This jaunty four-liner informs us about its writer as surely as a song does—saving us a look out the window—that there is a bird outside. The dialectal “love” tells us that he means it when he calls himself “a red nigger.” “A sound colonial education” may very well stand for the University of the West Indies from which Walcott graduated in 1953, although there is a lot more to this line, which we’ll deal with later. To say the least, we hear in it both scorn for the very locution typical of the master race and the pride of the native in receiving that education. “Dutch” is here because by blood Walcott is indeed part Dutch and part English. But given the nature of the realm, one thinks not so much about blood as about languages. Instead of, or along with, “Dutch” there could have been French, Hindi, Creole patois, Swahili, Japanese, Spanish of some Latin American denomination, and so forth—anything that one heard in the cradle or in the streets. The main thing, there, was English.

The way the third line arrives at “English in me” is remarkable in its subtlety. After “I have Dutch,” Walcott throws in “nigger,” sending the whole line into a jazzy, downward spin, so that when it swings up to “and English in me” we get a sense of terrific pride, indeed of grandeur, enhanced by this syncopated jolt between “English” and “in me.” From the height of “having English,” to which his voice climbs with the reluctance of humility but with the certitude of rhythm, the poet unleashes his oratorical power in “either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.” The dignity and astonishing vocal power of this statement are in direct proportion to both the realm in whose name he speaks and the oceanic space that surrounds it. When you hear such a voice, you know; the world is unfurling. This is what the author means when he says that he “love the sea.”

For the thirty years that Walcott has been at it, at this loving the sea, critics on both its sides kept calling him “a West Indian poet” or “a black poet from the Caribbean.” These definitions are as myopic and misleading as it would be to call the Saviour a Galilean. The comparison may seem extreme but is appropriate if only because each reductive impulse stems from the terror of the infinite; and when it comes to an appetite for the infinite, poetry often dwarfs creeds. The mental as well as spiritual cowardice, obvious in the attempts to render this man a regional writer, can be further explained by the unwillingness of the critical profession to admit that the great poet of the English language is a black man. It can also be attributed to degenerated helixes, or, as the Italians say, to retinas lined with ham. Still, its most benevolent explanation, surely, is a poor knowledge of geography.

Advertisement

For the West Indies are an archipelago about five times as large as the Greek one. If poetry is to be defined by physical reality, Walcott would end up with five times more material than that of the bard who also wrote in a dialect, the Ionian one at that, and who also loved the sea. When language encounters the absence of a heroic past a situation may emerge whereby the crest of a wave arrests the mind as fully as the siege of Troy. Indeed, the poet who seems to have a lot in common with Walcott is not English but rather the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, or the author of “On the Nature of Things.” The need to itemize the universe in which he found himself gives Walcott’s descriptive powers a truly epic character; what saves his lines from the genre’s frequent tedium, though, is the sparseness of his realm’s actual history and the quality of his ear for the English language, whose sensibility in itself is a history.

Quite apart from the matter of his own unique gifts, Walcott’s lines are so resonant and stereoscopic precisely because this “history” is eventful enough, because language itself is an epic device. Everything this poet touches reverberates like magnetic waves whose acoustics are psychological and whose implications echo. Of course, in that realm of his, in the West Indies, there is plenty to touch—the natural kingdom alone provides an abundance of fresh material; but here is an example of how this poet deals with that most de rigueur of all poetic subjects—the moon—which he makes speak for itself:

Slowly my body grows a single sound,

slowly I become

a bell,

an oval, disembodied vowel,

I grow, an owl,

an aureole, white fire.

(from “Metamorphoses, I/Moon”)

And here is how he himself speaks about this most poetic subject—or rather, here is what makes him speak about it:

…a moon ballooned from the Wireless Station. O

mirror, where a generation yearned

for whiteness, for candour, un- returned.

(from “Another Life”)

The psychological alliteration that almost forces the reader to see both of the moon’s o’s suggests not only the recurrent nature of this sight but also the repetitive character of looking at it. A human phenomenon, the latter is of a greater significance to this poet, and his description of those who do the looking and of their reasons for it astonishes the reader with its astronomical equation of black ovals to the white one. One senses here that the moon’s two o’s have mutated into the two r’s of “O mirror,” which, true to their consonant virtue, suggest “resisting reflection”; that the blame is being put neither on nature nor on people but on language and time. It’s the redundance of both time and language, and not the author’s choice, that is responsible for the equation of black and white—and that equation takes better care of the racial polarization this poet was born to than all his critics, with their professed impartiality, are capable of.

To put it simply, instead of indulging in racial self-assertion, which no doubt would have endeared him to both his potential foes and his champions, Walcott identifies himself with that “disembodied vowel” of the language which both parts of his equation share. The wisdom of this choice is, again, not so much his own as the wisdom of his language—better still, the wisdom of its letter: of black on white. He is like a pen that is aware of its movement, and it is this self-awareness that forces his lines into their graphic eloquence:

Virgin and ape, maid and malev- olent Moor,

their immortal coupling still halves the world.

He is your sacrificed beast, bellow- ing, goaded,

a black bull snarled in ribbons of its blood.

And yet, whatever fury girded

on that saffron-sunset turban, moon-shaped sword

was not his racial, panther-black revenge

pulsing her chamber with raw musk, its sweat,

but horror of the moon’s change,

of the corruption of an absolute,

like white fruit,

pulped ripe by fondling but doubly sweet.

(from “Goats and Monkeys”)

This is what a “sound colonial education” amounts to; this is what having “English in me” is all about. With equal right, Walcott could have said that he has in him Greek, Latin, Italian, German, Spanish, Russian, French: because of Homer, Lucretius, Ovid, Dante, Rilke, Machado, Lorca, Neruda, Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Pasternak, Baudelaire, Valéry, Apollinaire. These are not influences—they are the cells of his bloodstream. And if culture feels more palpable among urine-stunted trees through which “a mud path wriggles like a snake in flight,” hail the mud path.

Advertisement

And so the lyrical hero of Walcott’s poetry does. Sole guardian of the civilization grown hollow at the center, he stands on this mud path watching how “a fish plops, making rings / that marry the wide harbour” with “clouds curled like burnt-out papers at their edges” above it, with “telephone wires singing from pole to pole / parodying perspective.” In his keen-sightedness this poet resembles Joseph Banks, except that by setting his eyes on a plant “chained in its own dew” or on an object, he accomplishes something no naturalist is capable of—he animates them. To be sure, the realm needs it, not any less than he does himself in order to survive there. In any case, the realm pays him back, and hence lines like:

Slowly the water rat takes up its reed pen

and scribbles leisurely, the egret

on the mud tablet stamps its hieroglyph….

This is more than naming things in the garden—it is a bit later. Walcott’s poetry is Adamic in the sense that both he and his world have departed from Paradise—he, by tasting the fruit of knowledge; his world, by its political history.

“Ah brave third world!” he exclaims elsewhere, and a lot more has gone into this exclamation than simple anguish or exasperation. This is a comment of language upon a more than purely local failure of nerve and imagination; a reply of semantics to the meaningless and abundant reality, epic in its shabbiness. Abandoned, overgrown airstrips, dilapidated mansions of retired civil servants, shacks covered with corrugated iron, single-stack coastal vessels coughing like “relics out of Conrad,” four-wheeled corpses escaped from their junkyard cemeteries and rattling their bones past condominium pyramids, helpless or corrupt politicos and young ignoramuses ready to replace them while talking revolutionary garbage, “sharks with well-pressed fins / ripping we small fry off with razor grins”; a realm where “you bust your brain before you find a book,” where, if you turn on the radio, you may hear the captain of a white cruise boat insisting that a hurricane-stricken island reopen its duty-free shop no matter what, where “the poor still poor, whatever arse they catch,” where one sums up the deal the realm got by saying, “we was in chains, but chains made us unite, / now who have, good for them, and who blight, blight,” and where “beyond them the firelit mangrove swamps, / ibises practicing for postage stamps.”

Whether accepted or rejected, the colonial heritage remains a mesmerizing presence in the West Indies. Walcott seeks to break its spell neither by plunging “into incoherence of nostalgia” for a nonexistent past nor by finding for himself a niche in the culture of departed masters (into which he wouldn’t fit in the first place, because of the scope of his talent). He acts out of the belief that language is greater than its masters or its servants, that poetry, being its supreme version, is therefore an instrument of self-betterment for both; i.e., that it is a way to gain an identity superior to the confines of class, race, and ego. This is just plain common sense; this is also the most sound program of social change there is. But then, poetry is the most democratic art—it always starts from scratch. In a sense, a poet is indeed like a bird that chirps no matter what twig it alights on, hoping there is an audience, even if it’s only the leaves.

About these “leaves”—lives—mute or sibilant, faded or immobile, about their impotence and surrender, Walcott knows enough to make you look sideways from the page containing:

Sad is the felon’s love for the scratched wall,

beautiful the exhaustion of old towels,

and the patience of dented sauce- pans

seems mortally comic….

And you resume the reading only to find:

…I know how profound is the folding of a napkin

by a woman whose hair will go white….

For all its disheartening precision, this knowledge is free of modernist despair (which often disguises one’s shaky sense of superiority) and is conveyed in tones as level as its source. What saves Walcott’s lines from sounding hysterical is his belief that:

…time that makes us objects, multiplies

our natural loneliness…

which results in the following “heresy”:

…God’s loneliness moves in His smallest creatures.

No leaf, either up here or in the tropics, would like to hear this sort of thing, and that’s why they seldom clap to this bird’s song. Even a greater stillness is bound to follow after:

All of the epics are blown away with leaves,

blown with careful calculations on brown paper,

these were the only epics: the leaves….

The absence of response has done in many a poet, and in so many ways, the net result of which is that infamous equilibrium—or tautology—between cause and effect: silence. What prevents Walcott from striking a more than appropriate, in his case, tragic pose is not his ambition but his humility, which binds him and these “leaves” into one tight book: “…yet who am I…under the heels of the thousand / racing towards the exclamation of their single name, / Sauteurs!…”

Walcott is neither a traditionalist nor a modernist. None of the available -isms and the subsequent -ists will do for him. He belongs to no “school”; there are not many of them in the Caribbean, save those of fish. (One would be tempted to call him a metaphysical realist, but then realism is metaphysical by definition, as well as the other way around. Besides, that would smack of prose.) He can be naturalistic, expressionistic, surrealistic, imagistic, hermetic, confessional—you name it. He simply has absorbed, the way whales do the plankton or a paintbrush the palette, all the stylistic idioms the north could offer; now he is on his own, and in a big way.

His versatility in different meters and genres is enviable. In general, however, he gravitates to a lyrical monologue and to a narrative. That and his verse plays, as well as his tendency to write in cycles, again suggest an epic streak in this poet, and perhaps it’s time to take him up on that. For thirty years his throbbing and relentless lines have kept arriving on the English language like tidal waves, coagulating into an archipelago of poems without which the map of contemporary literature would be like wallpaper. He gives us more than himself or “a world”; he gives us a sense of infinity embodied in the language as well as in the ocean, which is always present in his poems: as their background or foreground, as their subject, or as their meter.

To put it differently, these poems represent a fusion of two versions of infinity: language and ocean. The common parent of the two elements is, it must be remembered, time. If the theory of evolution, especially the part of it that suggests we all came from the sea, holds any water, then both thematically and stylistically Derek Walcott’s poetry is the case of the highest and most logical evolution of the species. He was surely lucky to be born at this outskirt, at this crossroads of English and the Atlantic where both arrive in waves only to recoil. The same pattern of motion—ashore, and back to the horizon—is sustained in Walcott’s lines, thoughts, life.

Open a book by Walcott and see “…the grey, iron harbour / open on a sea-gull’s rusty hinge,” hear how “…the sky’s window rattles / at gears raked in reverse,” be warned that “At the end of the sentence, rain will begin. / At the rain’s edge, a sail….” This is the West Indies, this is that realm which once, in its innocence of history, mistook for “a light at the end of a tunnel / the lantern of a caravel” and paid for that dearly: it was a light at the tunnel’s entrance. This sort of thing happens often, to archipelagos as well as to individuals: in this sense, every man is an island. If, nevertheless, we must register this experience as West Indian and call this realm the West Indies, let’s do so, but let’s also clarify that we have in mind the place discovered by Columbus, colonized by the British, and immortalized by Walcott. We may add, too, that giving a place a status of lyrical reality is a more imaginative as well as a more generous act than discovering or exploiting something that was created already.

W.H. Auden in “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” wrote:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives.

There are few indeed who fall into that category; Derek Walcott is one of them. He is the man by whom the English language lives. Small particles of time ourselves, we are in a rather good position to empathize with its attitude toward language—an attitude of the lesser toward the greater. Time, therefore, is likely to worship language; for us, there is only reading.

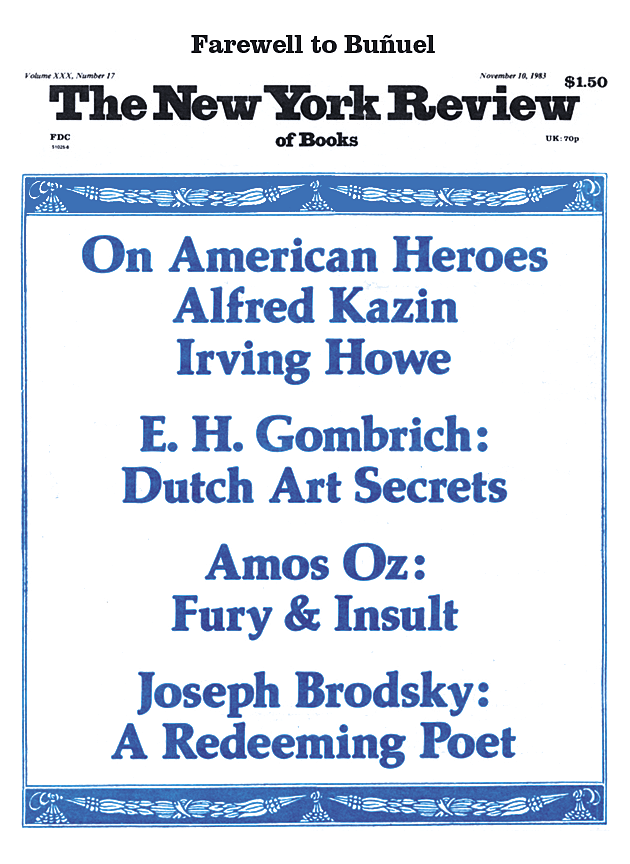

This Issue

November 10, 1983