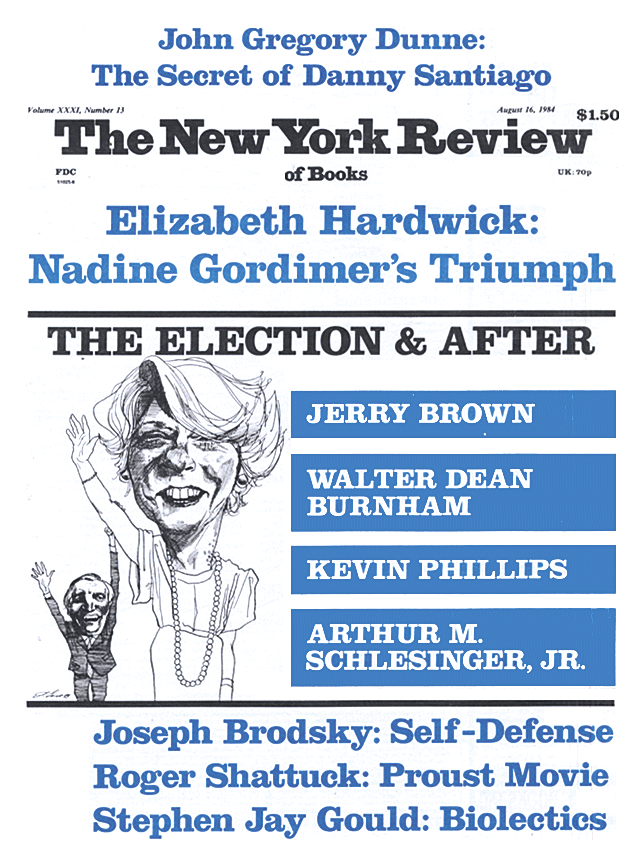

Following are excerpts from a discussion on the future of American politics held in New York in June between Edmund G. Brown, Jr., Walter Dean Burnham, Kevin Phillips, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. The discussion was sponsored by the Institute for National Strategy, of which Governor Brown and Walter Dean Burnham are members of the board of advisers:

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: We can start by saying that Reagan will probably defeat Mondale by a decisive margin of the popular vote, at least as great as, or possibly greater than, the 10 percent margin he achieved over Jimmy Carter. I see two basic reasons for this. First, at least as far as we can now determine, the economic situation in 1984 is tailor-made for reelecting an incumbent president. Secondly, Carter was rejected mainly because he was hopelessly inadequate in presenting himself as a leader and because he never was able to figure out, as many presidents have not, how to exercise the shamanistic functions of the presidency—what I once described as the president’s position as pontifex maximus of the American civil religion; there are only a handful of presidents who have done well at that, and Mr. Reagan is a master at it.

I would go further to say that quite apart from those considerations, there are longer-term changes in society and in politics that seem to point in the direction of a Reagan victory as well. Some have argued the race will be closer in the fall, but if we take a look at long-term party realignments that have occurred regionally over the past thirty years, several things make this doubtful.

First of all, the so-called majority party, the Democrats, has really not been a majority party in presidential elections since 1952, so far as I can determine. If we measure the proportionate Democratic vote from 1952 to 1980, during a generation of presidential elections, we find that the party has not grown nationally at all and that the mean percentage of the two-party vote received by the Democrats in those years was 47.6. Hardly the status of a majority party.

Secondly, if we look at the internal shifts that are taking place within the United States over this period, we come very close to what Kevin Phillips has written about extensively in the past. That is to say, we see something that looks like the system of 1896—when McKinley’s northern Republicans defeated Bryan’s southern and western Democrats—turned inside out with a few odd exceptions, perhaps Democratic Arkansas on one side of the line and Republican New Hampshire on the other. The old metropolis of the northeastern quarter of the country is now becoming more Democratic than the country as a whole. The increasingly populated Sunbelt has become more Republican than the country as a whole, in some cases by colossal margins. It is instructive to examine the current electoral strength of the parties as a statistical projection of the trend of past elections, putting aside all factors of personality, of “image,” and assuming they cancel out. (That is, we may assume Reagan scares people about the bomb but this is offset by admiration for, say, his handling of the economy, or for something else.) Such a projection shows not only the standard Democratic vote of 47.6 percent continuing, but an electoral vote of 104 for Mondale, and 434 for Reagan.

Moreover, if you pursue the projection a little further, one of the things that are absolutely fascinating is that there is now a built-in bias against the Democrats enlarging their share of the electoral vote. If we take account of the current geographical distribution of party strength, again as a purely statistical matter, Mr. Mondale has to get a minimum of 51.5 percent of the two-party vote in order to get a bare majority in the electoral college. That point should not be lost sight of because it is quite conceivable that Mr. Reagan, or maybe in 1988 Mr. Bush or somebody else, will wind up actually winning a presidential election while trailing in the popular vote. This of course, as we know, has happened before, the last time with Benjamin Harrison in 1888, and it will happen again. The system is biased toward Republicans partly because the realignment of the parties is most pronounced in states such as California where the increase in population, and therefore in electoral votes, has been greatest.

Quite aside from these neat statistics, as I listen to Walter Mondale, and I see how he has won his nomination, this seems an unpromising year for the Democrats. Just consider that Mondale has had to deal with the threat of Hart; with the problems of Jesse Jackson and the Jews, and of Tip O’Neill and the House leaders who angered the Hispanics by voting for the new immigration bill. In each case potential Democratic voters were estranged from the party. With Geraldine Ferraro as a running mate, he would risk further estranging voters in the South and West. A Democratic victory can’t be ruled out but I would not place much of a bet on it.

Advertisement

The next question to ask concerns the political situation that would emerge from Reagan’s reelection. This, I think, will depend very significantly, though by no means entirely, on the size of his electoral margin and the extent to which he will carry a majority in the Senate, and especially House, races.

It would seem reasonable to suppose that a really strong landslide would produce in the House a result roughly similar to those of 1968 and 1972, and of 1980, which ended with 243 Democrats, and 192 Republicans in the House. That still leaves Tip O’Neill as Speaker. The Republican opposition would have to run against him all the time in good weather or bad. But, as we can recall from Reagan’s counterrevolution of 1981, 192 Republicans are enough to give Reagan and his allies some sort of working control of the House on important issues. I assume that the GOP in any case will continue to hold on to the Senate, but with about three seats either way within the present 55–45 balance.

The basic point to bear in mind is that Reagan’s revolution is not finished. If he is reelected, especially by a wide margin, he will attempt to complete as much of it as possible before 1989. One can foresee at least the following elements in what I would describe as a minimum Reagan program.

First, the new administration will attempt to close the budget deficit. This is not as difficult to do in the short term as it may seem. A tax on consumers, whether it takes the form of a value-added tax, a turnover tax, or a tax on consumption, could readily produce $250 billion worth of additional federal revenues per year starting right away. It’s a terrific revenueraiser. The relevant advantages of doing this are that it is indirect, leaves alone big tax breaks for corporations and the rich, and can be made as regressive as one likes. So, it has all sorts of advantages. The political determination to close the gap will, I think, be generated sometime in 1985 or 1990.

Secondly, there will be an active promotion of a budget-balancing amendment designed to eliminate future efforts at reviving the liberal-activist state long after Reagan leaves the White House. We are two stages short of that now. I think that there will be a strong push for it if he is reelected.

Third—and this in some ways may be most important of all—Reagan if reelected will probably be able to appoint five new members of the Supreme Court. That many justices are in their late seventies and not all the others are in good health. We can anticipate the general philosophies of the new justices: they will resemble those of Rehnquist and O’Connor, if they are not still further to the right. It should not be difficult to foresee the consequences of this for the fortunes of economic conservatism, for the rights of criminal defendants, for giving legal sanction to crackdowns on the political dissent that, I am reasonably convinced, will rapidly build up during the later 1980s. The Court could also make basic changes on social issues—even overruling its own 1973 abortion decision in Roe vs. Wade. Then, of course, we could expect the arms build-up to continue, along with the confrontation with the USSR; we may well move from merely developing “star wars” technology to actually installing it in outer space.

One can imagine other trends. The basic domestic purpose of Reagan’s second term would be to reorganize the federal government in order to make sure that nothing like the Great Society programs can ever happen again. How far he will get obviously depends on the balance of forces he’ll have to work with, and contend with, because Mr. Reagan, as we well know, has shown himself capable of being pragmatic as well as ideological. That’s one of the things, along with his extraordinary liturgical talents, that make him such a remarkable president, a “Teflon president,” as they say, to whom egregious failures have not so far stuck. If he makes any retreat, he’ll do so not one moment before he has to.

I suspect that during the latter half of the 1980s we are going to run into situations of considerable political stress. That is partly because, it seems to me, the underlying crisis of the American political economy and empire, and for that matter, culture, will continue to unfold, no matter how popular Reagan seems to be this year. So far as I can judge, there is less positive support throughout the electorate for the Reagan program than there has been a rejection of the Democrats. They are seen as people who just don’t know what the hell they are doing, and who are not likely to provide the kind of impetus that many Americans feel leaders should supply.

Advertisement

But it would be a reasonable guess that we are going to have significant economic turmoil and probably serious recessions at some point between now and the end of the decade. Just how that will come about partly depends on what is done with the budget and the budget deficits. More generally, economic recession will continue to accelerate a social trend that was already in the works before Reagan took office, a trend that his counter-revolution has itself very considerably accelerated. And that is, of course, the general shift of the United States toward a roughly two-class society and toward policies that increasingly bear the pattern of regional triage—a writing off, among other things, of the older industrial regions of the North.

To refer to a two-class society overstates the matter. Our political and social system is one of the most complex, if not the most complex, in the history of the world. And yet, as we know, a very large part of the Democrats’ success in purchasing social stability and political harmony, insofar as they were able to do so during the preceding generation, was owing to their ability to make the most of the uniquely privileged position of the US in the world economy and to pursue a strategy based on the expansive idea of letting people have everything they want.

Of course many never got a dime’s worth out of it. But if you think back to the New Deal period there was a distinct opposition between classes in a situation of economic stagnation; and among the working class there were many who felt acutely deprived and were willing to organize politically to elect Roosevelt and Truman. By the middle 1970s—I should say—a very substantial part of the working class in this country became, in income and expectations, middle class, with the help of manufacturing jobs that paid $23 an hour, for example, and with the help of the dominant position of the American economy in the world capitalist economy at that time. What has been going on has been, as we all know, that the economic base for such employment opportunity has systematically shrunk. The US is good at creating jobs, and it has been creating them, but a great many of those jobs seem to be of the sort that replace a $23.50 per hour job with a $6.50 per hour job in some other line of work.

Tip O’Neill has been categorical and quite correct in stressing that it was the Democrats’ programs that permitted an enormous middle-class working class to develop since the 1940s. To a great extent its emergence was also made possible through government complicity with American business in the manipulation of US credit markets: by making available low interest and mortgage rates and, with them, the capacity to buy such things as houses and cars. The boost in interest rates and the collapse of the credit markets, the rise of foreign competition, the fact that the steelworker in South Korea makes 11 cents for every dollar an American steelworker makes—these are among the recent developments now undermining the new middle class.

Such threatening changes are not, in the long run, likely to stimulate enthusiasm for Reaganism and its slogans—get the federal government out of our hair, let the market decide, leave decisions to the states, etc. Instead they may well stimulate both a polarization of social forces and opportunities for political entrepreneurs to make demands that are hard to foresee precisely. They could conceivably take the form of demands for something as old-fashioned as social justice.

It is in any case very hard for me to see how consensus of the sort that Reagan and his friends might like to produce could survive the bursts of adversity that may possibly be coming—and the polarization which I think is almost certainly coming—without resorting to some sort of repression. I don’t know if they are going to try that. All I would suppose is that the quest for consensus is far more fragile than it looks at the moment.

KEVIN PHILLIPS: The Reagan administration, in my view, represents a profound transition in American politics. It is not the beginning of a classic realignment of the parties of the sort that has previously characterized the major shifts of American politics, for example in 1932. I think the United States and the world are in a period of enormous upheaval—a movement away from the old industrial phase of US domination after World War II and toward a postindustrial, high-technology era, both here and abroad, in which jobs have migrated from basic industries. There is certainly much uneasiness among the Western industrial powers. Attendant on this upheaval have been all kinds of changes in society and social patterns, and the two together have created, obviously, major changes in politics.

One of the underlying changes over the last twenty years didn’t get much credence until it was well advanced. This was a shift of the populist attitude in the US away from a fundamentally left-tilting political impetus to an increasingly right-tilted impetus, which displayed itself with Barry Goldwater and more with George Wallace, to some extent with Richard Nixon, and still more with Ronald Reagan. Now we are at the point where the regional constituencies that have been the most clearly populist in US politics, in the South and the West, have become the cutting edge of American politics and the American economy. Their populism has been mixed with a middle-class outlook that causes them to lean more in the conservative and Republican direction.

This, I think, has greatly destabilized and essentially subordinated the old Democratic New Deal coalition to the point where, as Walter Dean Burnham has demonstrated, the Democratic percentage of the typical presidential vote for the last thirty years has really begun to lag behind the Republican. If Ronald Reagan is reelected in 1984, as I think he will be, then come January 1989 sixteen of the previous twenty years will have passed under Republican administrations, with a four-year interregnum of a Georgia Democratic moderate who was out of sync with his party. This amounts to almost as long a span as the Roosevelt-Truman years.

Now, I’m not suggesting that this has resolved the shape of American politics for twenty-eight, or thirty-two, or thirty-six years as did the upheavals of 1800, or 1828, 1860, 1896, or 1932. I don’t believe that. I think we’ve gotten past the point that we can have a stable pattern for that long. The role of the political party has ebbed so much that parties can’t perform their old functions. The whole essence of the teletronic or technological upheaval, I think, is to consign to the scrapheap the old, more stable political and economic periods running from thirty-two to thirty-six years. We won’t have those now.

I think the outcome that we are moving toward will include a number of items that have been touched upon by Walter Dean Burnham. But I would look for more economic nationalism on the part of the United States and probably more economic activism from the forces that are ostensibly conservative. The trend toward the value-added tax seems to me a substantial one. But what is interesting here is that the battles over the larger issues seem more and more to be fought within the conservative coalition. Basic lines are being drawn, for example, between the supply-side and monetarist types who favor a flat tax and the so-called pragmatics, or business wing—which includes large elements of the old conservative establishment—who favor a value-added tax, a national sales tax, a business receipts tax, or some other form of tax on consumption.

Similarly I think the movement in the Supreme Court will have, obviously, an increasing conservative bias if the President is reelected, going further in the direction we have already seen in the decisions bearing on the Miranda case doctrine and hiring quotas. That general direction of jurisprudence would continue—I wouldn’t think to the point of provoking a violent counterrevolution, but to the point, certainly, of taking the emphasis off the entire liberal momentum that developed twenty years ago. Whether there will be a process of social stabilization, or a further push toward an insurgency by the underclass would depend on the extent to which the movement away from liberal social engineering is accompanied by a basic attempt on the part of government to rebuild the low-income and minority communities where they now are, including their housing, schools, and neighborhoods. That would mean using a fair amount of money and not elevating a balanced federal budget to holy writ.

For at least another five to ten years, I think we will see that the conservative-to-rightist tone of the major populist movement of recent times will continue. That movement still focuses on the tax revolt, the revolt against power structures in Washington and the state legislatures, the opposition to what we could call, I suppose, the Manhattan, Harvard, Beverly Hills culture. Populist claims will continue to concentrate on these issues rather than on egalitarian economic issues such as welfare or redistribution of wealth, which could benefit the left. I don’t see the present right-tilted populism dissipating because for it to dissipate you’d have to have a coherent alternative program of social democracy or economic populism articulated in the Democratic party; or you’d have to have a form of liberalism capable of mustering the support of ordinary Americans in the reasonable future. I think that’s five years or more away.

The major development in foreign policy is what could be called a new nationalism, which I think has some validity after the weak internationalism of the Carter administration. However, I think an analogy can be drawn between the approaches of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and that of the French Second Empire, with its desire to recapture past glories. Americans and the British are both pretending that the success of the British Navy in the South Atlantic or the United States in Grenada somehow recalls Sir Francis Drake and John Paul Jones. A large number of Americans would like to believe this, while many of those who condemn that belief, of course, helped lay the groundwork for it by tolerating the flagrant weakness of American policy during the late Seventies. Nevertheless it’s hard for me to see how any conceivable conservative foreign policy could represent a return to the old solidly based and assertive US strategy of the kind that we have seen before—under Eisenhower, for example—as opposed to the type of Second Empire politics I’ve mentioned. There’s more nostalgia in the new nationalism than Realpolitik.

Unless there is a major infusion of new voters into the electorate, the base for changing the present right-leaning drift of American politics is pretty thin. It would require that people from the large pool of nonvoters decide it is worth their while to vote. Now, whether or not the Reagan years, assuming that we have four more Reagan years, will generate that sort of militance is up in the air. I think it conceivably could. But, if by some chance, Reaganomics succeeds more than most of us here think, myself included, then I would doubt such militance will emerge. We already see some signs of the reaction of Democratic electorates to the tepid Democratic campaign so far this year. Enthusiasm has ebbed, partly, I think, because the Republicans are getting away with the theme of prosperity having returned. If the notion that “prosperity is in the air,” whether it is reality or myth, continues to placate the ostensibly disenfranchised electorates, then I’m not so sure there will be all that much more mobilization of voters, especially in 1984.

The odds favor the President’s reelection. I can’t think of a situation in which a president whose popularity ratings have been as high through so much of the election year has been defeated. In the ten elections of previously elected presidents who ran for another term in this century, in nine cases there were very clear verdicts. Six victories were by substantial margins; there were three losses by substantial margins. Only one man had a close race—Woodrow Wilson in 1916. The point is that by the time they’ve had a president they elected four years before for four years, American voters are capable of making a rather definite choice, one way or the other. In the President’s case at the moment, I would think it would be a favorable one.

True, the economic situation is somewhat more jerry-built than the Republicans want to admit. The prospects for 1985 and 1986 are very troublesome. And, to the extent that any of these situations began to develop faster than previous precedents would suggest, economic problems could move forward into the fall of 1984 and cause some problems for the President. But even there, the Democrats are inhibited by the fact that for the first time that I can remember, they are nominating the failed vice president of the administration defeated four years before. There is no precedent for that. Given the economic failures of the Carter-Mondale years, it somewhat undermines the ability of the Democrats to develop the economic case, should an economic case be susceptible to being developed in the fall.

Finally, the President’s second administration, if he has one, will be very greatly constrained by the weaknesses I’ve mentioned, along with the usual Republican inability to keep the economy going for any length of time without a recession. Seven of the last eight Republican administrations have had recessions in time for the midterm elections. By 1986, they may nip themselves in the bud again in much the same way. And I think that the real question is whether the institutional changes in American politics and economics can develop enough in the next four years to give the Republicans greater longevity than the transitional presidency of Ronald Reagan.

What we’re probably heading for in the next four to eight years is a more substantial upheaval and we still don’t know the precise shape of it.

BURNHAM: You’re saying 1986 will be a very good year for the Democrats?

PHILLIPS: Especially if they keep themselves well hidden and don’t present their own ideas. They get into trouble when they have to run on anything affirmative about the Democratic party. They do best in midterm elections when people forget how bad they were previously.

BURNHAM: That’s what we used to say about Republicans.

PHILLIPS: Maybe there’s a new sun and a new moon, to use Samuel Lubell’s phrase to describe the political shift that’s taken place.

EDMUND G. BROWN, JR.: And the Republican party’s the sun?

PHILLIPS: Well, the conservative side, in and out of the Republican party—I don’t think parties themselves are capable of playing the part of the “sun” anymore. However, if you look around Washington, in the last few years, most of the think tanks and institutions are on the more conservative side—even the Brookings Institution came out recently with what amounts to a fairly conservative tax proposal. It just seems to me more and more of the debate is being fought on what can be very generally called the center-right side. Even to the point where most of the debates are taking shape over issues as they are defined by the center-right—be it high-tech versus basic industry, “social issue” conservatism versus a more moderate approach to, say, abortion, “supply side” economics versus the concerns of the business community for fiscal management, and so forth. And the Democrats in these debates are not really very decisive. They usually support one side or the other in the conservative majority camps that seem to be calling more of the shots. I don’t mean necessarily calling the shots in the House of Representatives, but the larger power to determine the list and the shape of central issues, I think, has shifted in this country during the last ten to fifteen years and is now held more by the center-right.

ARTHUR M. SCHLESINGER, JR.: I reluctantly agree with my eminent colleagues about the short run. If the election were held today, Reagan would probably win by a substantial margin in the electoral college. I think the popular vote may be somewhat closer than suggested, but I may well be wrong on that.

Where I disagree is over the longer-run predictions. Politics, after all, is in the end the art of solving problems. Political tendencies rise or fall depending on the results they produce. If Reagan is reelected, the new four years will very likely be years of unrelieved disaster for him—too many chickens coming home to roost. If he had left office after his first term, he could claim an interesting niche in American history. He had altered the direction of American life, launched the counterrevolution against the New Deal, articulated new national goals, and restored faith in the workability of the political system.

You remember the gloomy writings of the late 1970s explaining (under the shadow of Jimmy Carter) how the fragmentation in Congress, the power of single-issue groups, and so on were dooming the presidency to ineffectuality. Reagan has shown that, even if a program doesn’t make much sense, effective leadership can still get it enacted. Had he retired after his first term, he would have gone down as a surprisingly effective president. But presidents always find it hard to retire.

Now, I think that the next four years are going to be years of great trouble. The larger the margin by which Reagan wins, the more trouble he will be in. We all know what happened to FDR and to Lyndon Johnson and to Richard Nixon after they won reelection by very large margins. Triumphant reelection diminishes a president’s sense of reality. In Reagan’s case, he would very likely interpret reelection as a decisive mandate, a mandate to balance the budget by cutting entitlements and imposing regressive taxation; a mandate to intervene militarily in Central America; a mandate to pursue the arms race, and so on.

I think that that will produce a great deal of trouble for him and lay the groundwork for reaction against him—a reaction which in my view is about due anyway. I hate to bore my colleagues by saying why I believe it is due, but, following my father and Henry Adams, I find a discernible cyclical rhythm in American politics. I have long been puzzled to define the nature of that rhythm with precision. Conservatism and liberalism don’t seem sufficiently precise terms. Quietism and activism are refuted by Reagan, who is certainly in his way an activist president. Albert O. Hirschman offers the best definition in his book Shifting Involvements, portraying the alternation as between “public action” and “private interest.”

In general, we go through periods of action, passion, idealism, and reform that continue until the country is worn out by the process and disenchanted with the results. Then we enter a period where public action recedes and private interest dominates. This goes on, ordinarily, in this century, for a shorter period. The complete cycle would appear to last about thirty years. When Henry Adams wrote about it, he spoke of a twentyfour-year cycle in the early republic from one period of centralization of energy to the next. Our life expectancy today is longer: hence the cycle is now one of thirty years: Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, FDR in 1933, JFK in 1961.

The generational effect is very evident. In each case, the leaders in the publicaction phase of the cycle had their formative political experiences in the preceding public-action phase. Thus, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman were young men when Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were setting the tone of the country. John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were young men when Franklin D. Roosevelt was dominating the country.

The Kennedy generation is soon due to come along. Gary Hart—or even earlier, Jerry Brown—may turn out to have been John the Baptist. The time is bound to come when those people whose values were shaped and ideals were formed in the Kennedy years come into their own—as the children of the Roosevelt years did in the 1960s, and as the children of the progressive period did in the 1930s.

So I would suppose that somewhere in the late 1980s or early 1990s the failure of the Reagan administration to solve the problems combined with the cyclical rhythm bringing a new generation into salience will produce a very significant change in the direction of American life.

Now, I know some look at the current conservative period and feel that there are things in it that suggest a greater permanence for conservatism today than was the case in past conservative epochs. Maybe so; but, so far as I can see, the current conservative period simply reenacts the major characteristics of the other conservative periods of this century.

Take a look at twentieth-century political history. We began with the so-called progressive period—two demanding presidents exhorting the American people first to democratize their political and economic institutions at home and then to make the world safe for democracy. Twenty years of high political living wore the country out and disillusioned people with the idea of public action. So we went into a decade, the Twenties, dominated by private interest. This got us into trouble; so we had the Thirties and Forties—two more decades of public action. Once again fatigue and disenchantment; so we had a time of respite and private interest in the Fifties.

The Sixties represented the next season of public action—Kennedy and the New Frontier, Johnson and the Great Society, the racial revolution and the war on poverty. This time the energies released took a destructive turn after the murder at Dallas and with the Vietnam War, and they finally threatened to tear the social fabric apart. Nixon won the presidency in 1968 with only 43 percent of the vote. Still his first term showed that the publication tide was still flowing—the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, the proposed Family Assistance Program.

But with so much social upheaval—riots in the cities, turmoil on the campuses, two more terrible assassinations, Watergate and the fall of a president—compressed in so short a period, the season of public action did not run its normal two decades. Sometime in the Seventies we entered another period of private interest, comparable to the Fifties and the Twenties—a period of which the later Nixon, Ford, and Carter were expressions and Reagan is the culmination.

The present conservative swing is especially reminiscent of the Twenties. You have the same dominance of trickledown economics, or, as it is now called, supply-side economics. You have the same crusade against regulation. You have the same desire to devolve federal powers on the states and to dismantle the federal administrative apparatus. You have the same pretentious intellectualizing and “agenda-setting,” which in the 1920s was called the “new era” philosophy, in the 1950s “new conservatism,” and now takes the form of “neoconservatism.”

You also have the same division, which Kevin Phillips has written eloquently about, between the business community and the fundamentalists in the conservative coalition. In the 1920s, the fundamentalists imposed prohibition on a hapless country. They did their best to stop the teaching of Darwin. This was the supreme period of the Moral Majority, even if the term was unknown. It was the age of Aimee Semple McPherson and Billy Sunday; it was the time when Sinclair Lewis wrote about Elmer Gantry. You had the same division in the conservative coalition over the question of prohibition that you have today over questions like abortion and drugs. The businessmen who dominated economic policy in the private-interest administrations of the 1920s patronized bootleggers and accepted evolution, while the fundamentalist wing of the conservative coalition demanded stricter enforcement of prohibition and creationism in the public schools.

To mention a more mundane recurrence, consider corruption. Public-action administrations tend to attract idealists who, whatever their other defects, do not steal. The kind of corruption that is invited by government regulation and by the disbursement of government funds tends to rise only at the weary end of public-action administrations. But private-interest administrations are staffed from the start by people who are in there to enrich themselves or their industries. So corruption becomes rampant in the Harding, Eisenhower, and Reagan administrations.

The characteristics of the present conservative spasm do not seem to me to argue for greater expectation of longevity than in previous periods dominated by private interest. The recoil against Reagan coinciding with the generational shift will very likely produce, somewhere shortly before or shortly after 1990, a shift in the nation’s direction as vivid in its effects as when Theodore Roosevelt took over in 1901, or FDR in 1933, or JFK in 1961.

To conclude with one other point, both Kevin Phillips and Walter Dean Burnham have suggested that the intellectual incoherence of the Democratic party will stand in the way of a turning to the Democrats. I’m not so sure if that’s the case. Historically we vote to put regimes out, not to get them in. The 1980 election was not a mandate for Reaganism. It represented an overwhelming national desire to get rid of Carter. The election of 1932 was not a mandate for the New Deal. It represented an overwhelming national desire to get rid of Hoover. The Democratic party today seems to me in a situation much like that of the Democratic party between 1928 and 1932. There are plenty of ideas and plenty of bright people. But there is no coherent blueprint. I don’t think there is any need, politically or even morally, to present a coherent blueprint. Nor do I think that the absence of a detailed, programmatic alternative will impede the cyclical change. I think that there are plenty of ideas and plenty of people with ideas so that a new Democratic president interested in innovation would not be embarrassed by an absence of proposals.

PHILLIPS: If as you say—and I agree—an era of activism is overdue, there is a mystery about just what forces will produce one. We have to ask, first, just what historical pressures were at work during the cycles you mention to produce competent leadership when it was needed. That’s quite a different issue from the one of whether the leader of the Democratic coalition can put together an effective program during the next few years. If the Democrats nominate somebody as conventional as Walter Mondale in 1988 or 1992, are they going to be able to deal successfully with the situation they will face—whether or not they win the election? And if the Reagan administration can’t pull it off, and I’m willing to think there’s a very good chance it won’t, I guess my larger question, and I think Walter Burnham’s as well, is whether in both parties coalitions will have become obsolescent.

Since 1856, the Republican and Democratic coalitions have dominated American politics, American administrations. If the Reagan administration fails, they will both have run out of legitimacy and effectiveness within the last ten years. Now I don’t believe there’s a precedent for that pattern of double failure and double obsolescence, if it occurs. Not unless we go back to the 1850s. The Democrats will have more difficulty than ever before in mobilizing to take advantage if the Republicans fail—as I think they may. I’m therefore wondering whether we can presuppose that active leadership will emerge according to a cyclical pattern. And I think that is Walter Dean Burnham’s point as well.

SCHLESINGER: It all depends on how great the failure is. Take the thesis advanced by the political analyst Horace Busby that the Sunbelt is irretrievably lost to the Democrats. This assumes that the same kind of political divisions that economic trouble imposed on the rest of the country will not affect the Sunbelt, no matter how severe the coming difficulties. If the afflictions are great enough, I think there will be enough votes.

BURNHAM: Suppose you have the situation like the one where Carter and company demonstrated an incompetence to understand the world we are now living in, or to fashion the kind of policies that made sense, or were widely acceptable. Then suppose we find Mr. Reagan leading us down a path to perhaps even more baroque disasters in the second half of the 1980s, leaving the great American public utterly disenchanted and thrashing around. I think your proposition is that sooner or later the system somehow boils up to the top. Leaders would take charge of a messy situation, and march on. After all, when Wilson failed catastrophically in 1920, you had eight years of Republicanism and then the economic roof caved in, and Hoover, who was rather like Carter in many respects, was flushed out. FDR came to power, not because people were voting for him or the Democrats but because they were voting against the other side. In fact, right in the middle of the 1920s, articles were being written in Harper’s and elsewhere asking, “Is the Democratic party finally dead?” And Will Rogers said, “I belong to no organized political party, I’m a Democrat.” The Democrats of the 1920s and of today have all too many similarities. Yet, FDR suddenly appeared. Your argument tends to be that whatever the processes are that produce such leadership, they will occur again.

I have to be very agnostic about this, for a number of reasons. First, we’ve seen the remarkable phenomenon by which the traditional functions of the parties are being replaced by the “permanent political campaign” based on continuous, hyped-up personal promotion of one candidate or another through the mass media. Second, we pay too little attention to the long-term pressures of international politics on the domestic electoral market. The economic nationalism that Kevin Phillips speaks of may seem a nice idea, but runs directly against our geo-imperial interest. It is very hard to see how you can manage a policy of nationalism—whether of the McKinley or Alfonsin type—while you’re busy trying to run a world empire. If we seriously become economic nationalists we will be widely copied by the other industrial nations, taking us all back to the “beggar thy neighbor” horrors of the 1930s. The countries that must “export or die,” such as West Germany and Britain and especially Japan, are going to be in very tough shape.

Some may say “let ’em fry,” but people have a habit of reacting in a rather hostile way when that occurs and you create all sorts of problems for yourself, especially when you’re trying to manage a world order in addition to the homefront. If the US is going to have to accept a declining share of global trade, the American working class in my view is going to have to expect less, one way or another, and that includes an awful lot of people who now regard themselves as middle class. And how far they go back, under what conditions they go back, with what kind of “safety net,” job retraining, and other kinds of protection—these will be central political questions.

Between now and the end of the century, I’m told, some 750 million new workers will be added to the noncommunist world. An awful lot of them are going to be hungry; they’re going to be willing to work for little money and they will be conveniently living under the kinds of dictatorship that, say, Pinochet has in Chile, or that we find in South Korea; they do a great job of keeping factory labor costs low. Since you can transfer billions of dollars from here to Seoul or Munich in five minutes—while labor is far less mobile—you’ve got a real problem on your hands: a continuing, tightening squeeze so long as you don’t install full-scale economic nationalism in the US—and that would bring on other problems I’ve mentioned.

PHILLIPS: We have to ask, what is going to be the political impact of downward mobility of large parts of the American middle class—in effect the collapse of the American Dream—and historically, I believe, the effect is that the poorer minorities, such as the blacks, tilt toward the left and the middle class moves to the right.

SCHLESINGER: Downward mobility of the middle class in the Depression was left-tilting.

BURNHAM: But don’t forget that the Great Depression was a generalized event, a collapse of civilization as we’ve known it that affected all classes across the board. The swing against Hoover went from top to bottom. An awful lot of businessmen were going broke or were terrified that they would wind up losing their jobs. There was 25 percent unemployment. The state was not seen—as it is now—as part of the problem, but as an indispensable mechanism for a solution. In any case, if we project a large-scale collapse, we should also consider the extent to which it can produce a kind of right-wing populist backlash in the short term, one formed in the spirit of Brecht’s line from the Threepenny Opera, “First feed the face, then talk right and wrong.”

The new immigration bill, for example, is very mean-spirited. Many people in the labor movement supporting it share a kind of shut-it-off mentality in reaction to the huge influx of people from Mexico. And Mexico’s population, of course, is exploding through the roof. What we’ve got is not a general collapse as in the 1930s. We have an extremely differentiated one, in which, so far as I can judge, a key to the problem might be the growing sense—and the immigration bill is only one sign of it—among the white population that they are under siege from a largely colored and hungry world out there. We should ask whether we will see here the emergence of the kind of siege mentality that transformed Afrikaner politics in the South African election of 1948—the mentality of “let’s rally around.” This is obviously what happened in Israel, with the rise of the Likud. It’s not an economic movement so much as a right-wing preservationist movement.

SCHLESINGER: Nationalism is the essence of Reaganism in foreign policy—but I think that will go, in its strident form, when Reaganism goes.

BURNHAM: I think it will too, but these are things that we really haven’t had to confront before in our history.

PHILLIPS: Reagan, for all that he’s put down, is, in my view, a force against development of a harsh policy both on the trade and immigration fronts because of his free-market views. A successor conservative regime, one more interested in pulling away labor voters, would take a much tougher line on trade and immigration. Somebody like John Connally, or George Wallace if he were running, could go in this direction. They would have support from plenty of Democratic politicians who can’t succeed within the Democratic assumptions and whose constituencies would be vulnerable to a raid on those issues.

On the other hand, a number of prominent Republican and business leaders are thinking seriously about ideas for industrial strategies to restore US competitiveness and industrial strength. It’s possible that the only chance for such blueprints to develop momentum lies with the center-right—just as it took Nixon to go to China.

BROWN: Unlike South Africa, America can’t withdraw into its shell—especially in view of the loans provided by American banks, the role of the dollar in international transactions and of the US as the guarantor of the international economy. We can’t withdraw without hurting ourselves. A rational assessment of our choices argues, I believe, for a greater commitment to increasing the level of skill within the United States as a way of expanding wealth. It argues for developing effective national economic strategies in order to compete with the countries using new technology in the cheap labor markets abroad. Such strategies would require a national consensus in which more people felt they had a stake, and, in my view, that would require a decent level of perceived equity throughout our society. It is really inconsistent with a continuation of privileges for a few and spreading misery for the many.

This is not the 1930s or the 1920s where some kind of isolationism might make sense. It just doesn’t make economic sense because we depend on our ability to compete abroad. And we can compete abroad only if we have products and services that foreign countries need or that can be sold in competition with what they themselves can produce. And that is going to require improved technology, which depends on investment in education, in retraining, not to mention the willingness and motivation of the work force. There is a shortage of trained people throughout the American economy. If anything, the immigration of both highly skilled and unskilled foreigners indicates that we don’t have enough labor to do certain jobs for which there is demand.

So I believe an increasing pressure exists to invest in people who have been left out—minorities, women, and workers in failing industries. A more balanced program of economic opportunity seems an essential precondition for the national consensus that is needed if we are to sustain the kind of growth that can compete with Japan and Korea and other parts of the world. These countries use not only cheaper labor and new technology but targeted economic planning made possible by their own consensus—as in the case of Japan—or by dictatorship, in the case of some of the other countries. And given our own traditions, I doubt we would readily accept an unfair, inequitable, authoritarian solution without a battle. The only other choice is a national policy that would be based on far broader popular agreement than we now have.

It is true that the putative custodian of this broader vision, the Democratic party, is weak. The party is suffering badly from fragmentation by special interests; the corrupting influence of money is being felt in a very deep way, and this corruption lies not in particular transactions or the buying of particular votes, but rather in the deep absorption in fund raising that is now part of the political process.

More and more of the energies of elected officials have to go into figuring out cleverer ways of raising money. And therefore less and less time goes into constructing a program and mobilizing the poorer groups within the society. So the Republicans with their ten-to-one financing advantage, their technological superiority in their mail campaigns, their greater capacity to work through their national committees, have a distinct advantage.

In response, the Democrats are being forced to go for their financing to interest groups that are Republican in inclination. And so you basically have one source of money fueling the election. You don’t have a Democratic party representing—and being financed from—a broad base. And even worse, money contributed for chiefly ideological reasons comes predominantly from the right—in the small $10 and $15 donations that flow into the campaigns of Jesse Helms or the Moral Majority or some of the right-leaning congressional candidates. You don’t find as much of that sort of money on the left or in the center or from traditional Democratic constituencies. And that definitely is creating an imbalance that is favoring the Republicans.

In addition, the plebiscitary character of contemporary politics is also favoring the conservatives. In California, the propositions that started in 1978 with Howard Jarvis and Proposition 13 were quickly followed later in 1978 by Proposition 4 to limit taxation; two years after that, a victims bill of rights was promoted by the same cast of characters that started Proposition 13. In 1982 the inheritance tax was entirely abolished by popular vote. This June the conservatives passed an initiative sharply curtailing the powers of the Democratic majority in the state legislature. And now new conservative initiatives are being proposed to ban gun control and limit welfare. So, the reality now is that the old progressive reforms of initiative and the referendum are a tool in the hands of very conservative forces.

SCHLESINGER: That’s where direct democracy gets you.

BROWN: Still, if mechanically, financially, technologically politics are definitely tending in a conservative, rightward direction—one that favors military investment above all—the international economic pressure, I believe, is going to test the thesis of increasing military buildup. If half the good scientists are working for the military, with very weak benefits for the civilian economy, that can’t go on forever. If Japan and other countries are able to put their best scientists into commercial competition, then it’s going to become clear sooner or later that we have to make a greater investment in our commercial capacity to compete with these foreign economies. But that runs head into the problem that we are not graduating enough or training enough skilled people for the industries we now have. So ultimately, I think, we will have to make two choices. First we will have to put less into the military so that we can divert more skills and intelligence toward the international commercial struggle—a struggle that is not a hypothetical possibility of nuclear conflict with Russia, but occurs daily when people buy TVs, cars, watches, tools, steel, and textiles. And second, the winning of it can’t be just through protective tariffs. It is going to require improved education, retraining, convincing incentives, and coherent economic strategies in which the government would have to be strongly involved. All of these are different from what we are now offered on the Republican side, and could hardly be expected under the conditions of increasing “polarization” that we have been discussing.

This Issue

August 16, 1984